Include Métis, Inuit in Indigenous vaccination plans

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/02/2021 (1747 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This week, and for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic began, a small amount of off-reserve, urban First Nations people in Manitoba could book a vaccine appointment.

It’s an encouraging new trend.

First Nations have been administering vaccines to on-reserve residents — mostly health-care workers, elders, and long-term care residents. A few have allowed elders living off-reserve to come home and be vaccinated, too.

But now, all First Nations citizens in Manitoba, born in 1948 or earlier (aged 73 or above), can book immunization appointments.

Other Manitobans must be born in 1928 or earlier (93 or above).

Vaccinating Indigenous communities must be a priority for all Manitobans because they are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and suffer more deaths. The virus is also difficult to eliminate due to chronic issues of poverty and a lack of adequate housing and health infrastructure.

Simply put: in order for us to win the fight against COVID-19, we must focus on eliminating it in the places it is hardest to eradicate.

Indigenous communities are those places.

Even Canada’s national vaccine rollout lists “Indigenous adults where infection can have disproportionate consequences” a “Stage 1” priority.

The problem is that provincial health agencies, which deliver the vaccines, are having trouble determining who is Indigenous.

While First Nations now appear to be fully included in Manitoba’s Indigenous vaccine rollout plans, Métis and Inuit are not.

This means that until something changes, nearly 41 per cent of Manitoba’s Indigenous population (around 90,000 Métis and 1,000 Inuit) will have to wait alongside other Manitobans to get the vaccine.

On Wednesday, David Chartrand, president of the Manitoba Métis Federation, called the omission “insulting” and pointed out that Métis face much of the same oppression, poverty, and health issues as First Nations.

A similar statement was made by Rachel Dutton, executive director of the Manitoba Inuit Association.

In a press release, Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Grand Chief Arlen Dumas called on the MMF to “produce a report on COVID-19 prevalence within the Métis population so that a similar process of evidence based vaccine prioritization can proceed.”

Chartrand countered with complaints that provincial health authorities don’t have a mechanism to adequately identify First Nations citizens, so the authorities are reliant on “self-declaration,” encouraging people to “lie” and “deny their identity.”

As Dr. Marcia Anderson, lead for the Manitoba First Nations pandemic response team, said Wednesday, it is “a violation of Indigenous rights” to require proof of Indian status.

Many First Nations people, Anderson points out, have lost their status due to Canadian policies that “enfranchised” women who married non-Indian men, soldiers, and children adopted into foster families.

While some laws have allowed the ability to get status back, this process takes years — even decades — and is based in proving blood quantum, violating Indigenous rights to determine membership based on their own values and traditions.

First Nations peoples, Dr. Anderson said, should be determining who is First Nations — something she promised will happen “in the coming week” to shut out the “pretendians.”

Identifying people who are pretending to be Indigenous isn’t easy, though.

In January, billionaire Canadian casino executive Rodney Baker and his wife flew to a northern Indigenous community in the Yukon and posed as locals to get a vaccine shot.

There are countless other cases of non-Indigenous peoples claiming Indigenous identity to access treaty rights, money, and privilege in the film, literary, and art industry. Exposing fakes often takes years and much investigation.

Now, because the province excluded Métis and Inuit its vaccine rollout, we have a fight between Indigenous leadership over who should get it, who is Indigenous, and no clear process to determine Indigenous identity.

Want a solution? It’s easy.

Let Indigenous peoples decide.

In B.C. this past week, provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said all Indigenous people would be eligible to get their shots 15 years younger than the rest of the population.

Henry said she did this at the direction of Mary-Ellen Turpel-Lafond, a Cree woman and former provincial child advocate, who headed up an investigation into the B.C. health-care system that found widescale racism against Indigenous peoples.

Explaining why Métis were included in B.C.’s vaccination plans, Dr. Daniele Behn Smith, deputy provincial health officer for Indigenous Health, said it was crucial to have Métis people “feel seen.”

If Manitoba’s health leaders empowered Manitoba’s three Indigenous groups, treated them similarly, and let them lead the vaccine rollout, there would be far less conflict at a time when we need to all work together.

Instead of celebrating an encouraging new trend though, we got very old divisions, politics, and finger-pointing.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

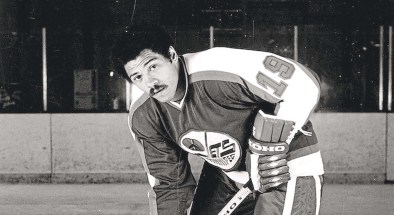

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.