Toxic terminology Use of 'patient zero' spreads quickly, but can leave a trail of despair in its wake

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/01/2021 (1874 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It sounds like the name of a Hollywood thriller — The Hunt for Patient Zero.

The phrase “patient zero” has been on the minds and lips of much of the world as the search continues for the first documented human case of the COVID-19 virus that has so far claimed more than two million lives around the globe, including more than 18,000 in Canada.

According to the World Health Organization, it’s a search that may never yield an answer.

“We need to be careful about the use of the phrase ‘patient zero,’ which many people indicate as the first initial case,” Maria Van Kerkhove, the WHO’s technical lead on COVID-19, said last week. “We may never find who patient zero was. What we need to do is follow the science and follow the studies.”

Chinese authorities originally reported the first coronavirus case was on Dec. 31, 2019, and many of the first cases of the pneumonia-like infection were immediately connected to a seafood and animal market in Wuhan, in the Hubei province.

But those reports have been disputed and rumours abound. And while the media adores the phrase “patient zero,” researchers tend to avoid it (Warning: bad pun ahead) like the plague because it is often incorrect, and can lead to disinformation and scapegoating of the innocent.

But this is far from the first outbreak where the term has become part of the daily lexicon, as see from today’s historic list of Five Health Crises Blamed (Rightly or Wrongly) on Patients Zero:

5) The outbreak: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

The (possible) patient zero: Dr. Liu Jianlun

The viral story: In 2003, a coronavirus that killed one in every 10 people it infected emerged from China and spread through several countries. Eight months later, it petered out.

Scientists have traced a super-spreading event during the global outbreak of SARS to one doctor and one night that he spent in a Hong Kong hotel, according to a WHO bulletin.

A report from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty states that on Feb. 21, 2003, mainland Chinese doctor Liu Jianlun, 64, who had secretly been treating patients of the disease that would become known as SARS in Guangdong, travelled to Hong Kong to attend a wedding.

“After he checked into a room on the (Hotel) Metropole’s ninth floor, a fever Liu had been struggling with worsened. By the time he admitted himself into a nearby hospital with advanced symptoms of the new virus, several tourists staying at the Metropole had been infected, possibly as a result of Liu vomiting in a corridor. He died on March 4 after admitting to doctors that he had been dealing with the strange viral outbreak in mainland China,” the story states.

“Hong Kong authorities moved swiftly to attempt containment of the outbreak, but by the time the alarm had been raised, several infected Metropole guests had checked out and unwittingly carried the coronavirus to their respective home countries.”

An elderly woman flew home to Canada on Feb. 23, greeting her son with a hug. In less than three weeks, both were dead and Canada had become one of the world’s SARS hot spots. It is believed to have originated in bat species and then spread to other animals before infecting humans in China.

“You wouldn’t call him (Dr. Liu) ‘patient zero,’ but if you consider his impact in terms of the outbreak, he was critical in the spread of the disease,” Dr. Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology and director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University in New York, told CNN.

4) The outbreak: Ebola

The (possible) patient zero: Two-year-old Emile Ouamouno

The viral story: The 2014 to 2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa was the largest since the deadly virus responsible was first discovered in 1976. It killed in excess of 11,000 people and infected more than 28,000, according to the WHO. The outbreak was found in 10 countries, mostly in Africa but there were also cases reported in the U.S., Spain, the United Kingdom and Italy.

Scientists have traced this outbreak to a two-year-old child who lived in a small rainforest village in southern Guinea. His name was Emile Ouamouno, but to the world he became known as Ebola’s “Patient Zero.”

The researchers made the connection on an expedition to the boy’s village, Meliandou, taking samples and chatting to locals to learn more about the outbreak’s source before publishing their findings. It’s not known with absolute certainty how little Emile became infected, but it’s likely he became sick after playing in a hollow tree housing a colony of bats.

Ebola can be spread from animals to humans through infected fluids or tissue. “The child may have contracted the disease through contact with a fruit bat, as the animals are reservoirs of the virus. Most likely, the outbreak started from only this toddler and no one else, the researchers said, because their genetic analysis of the viruses found in multiple patients’ blood samples showed great similarities within the samples,” livestream.com reported, citing the New England Journal of Medicine.

In December 2014, Emile had a fever, black stool and started vomiting. He was dead four days later. Within a month, so were his young sister, his mother and his grandmother. CNN reported the illness spread like wildfire outside their village after several people attended the grandmother’s funeral. For Emile’s father, however, it all came back to his son.

“Emile liked to listen to the radio, and his sister liked to carry babies on her back,” Emile’s grieving father, Etienne Ouamouno, told a communication officer for the United Nations’ children’s agency, UNICEF.

3) The outbreak: The so-called “Spanish flu”

The (possible) patient zero: Private Albert M. Gitchell

The viral story: Just before breakfast on the morning of March 4, 1918, Pte. Albert Gitchell of the U.S. Army reported to the hospital at Camp Funston at Fort Riley, Kansas. Gitchell, a camp cook, complained of the cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. He was hospitalized with a 104-degree fever.

“Gitchell was quickly banished to a contagious ward. Hardly had a corpsman put a thermometer in the soldier’s mouth when Cpl. Lee W. Drake from the First Battalion, Headquarters Transportation Detachment, reported to the same admitting desk in Building 91. His symptoms, even to a 103° fever, were identical with Gitchell’s,” according to 1961’s The Great Epidemic: When the Spanish Influenza Struck.

Notes history.com: “By noon, over 100 of his fellow soldiers had reported similar symptoms, marking what are believed to be the first cases in the historic influenza pandemic of 1918, later known as Spanish flu.”

The last great pandemic — which did not originate in Spain — has been described as ‘the greatest tidal wave of death since the Black Death, perhaps in the whole of human history.”

The pandemic, caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus, killed an estimated 20 million to 50 million victims worldwide from 1918-20, including about 55,000 across Canada and at least 1,200 in Winnipeg, which had a population of roughly 180,000 at the time. It infected 500 million people – about a third of the world’s population at the time – in four successive waves.

The disease travelled to Europe with American soldiers, wreaking international havoc. It flared again in North America with the return of troops after the Great War ended.

As for Gitchell, it’s considered highly unlikely he was patient zero, although he got more than his 15 minutes of fame. He reportedly survived the flu and the war and died in the South Dakota State Soldiers’ Home in 1968.

2) The outbreak: HIV/AIDS

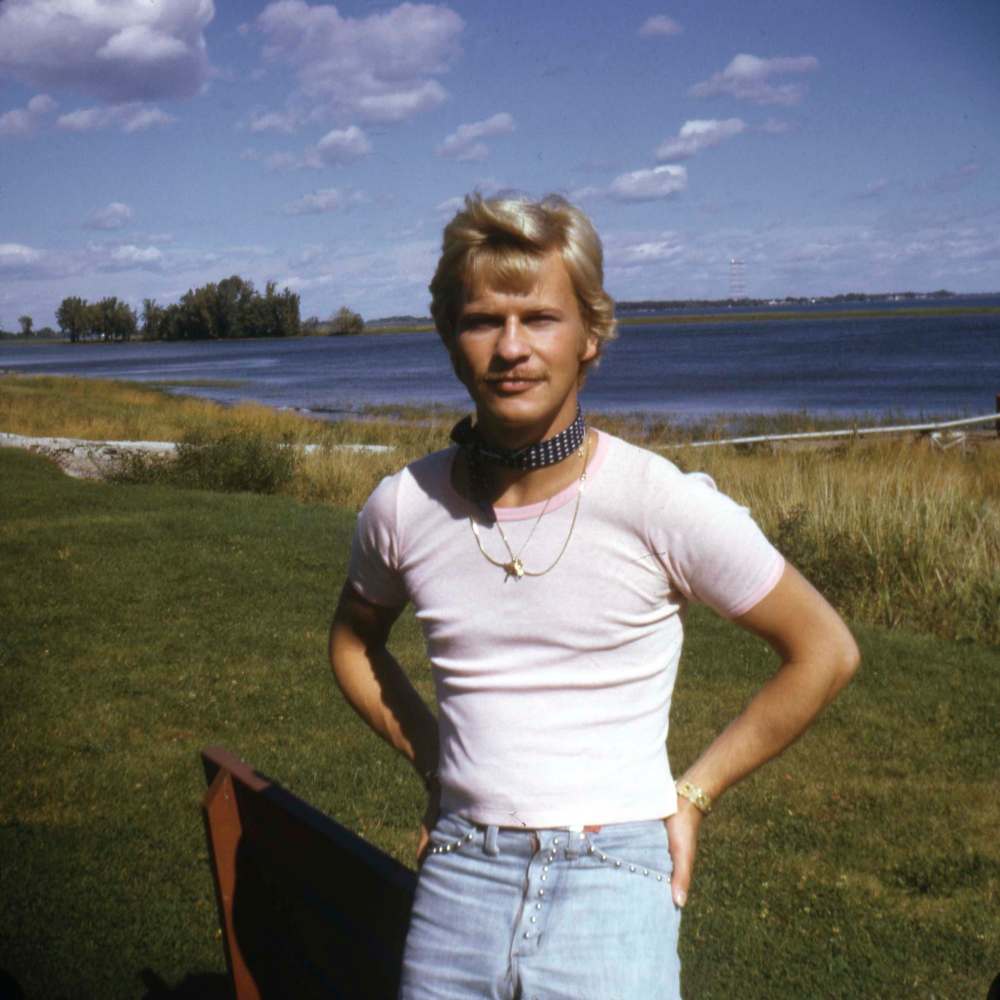

The (possible) patient zero: French-Canadian flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas

The viral story: We may rarely know the true first case of a new deadly disease, but we do know the origins of the toxic term “patient zero.”

When a researcher’s scrawling of the letter O was misinterpreted as a zero in reference to an HIV patient in the early 1980s, it led to the horrific vilification of Gaëtan Dugas, a French-Canadian flight attendant who was wrongly blamed for bringing the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, to the United States.

In 1981, researchers at the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention first documented a mysterious disease. In their research, they linked HIV to sexual activity.

“The researchers began to study one cluster of homosexual men with HIV, and beginning in California, they eventually connected more than 40 men in 10 American cities to this network,” CNN reported in 2016.

“Dugas was placed near the centre of this cluster, and the researchers identified him as patient O, an abbreviation to indicate that he resided outside California.”

Tragically, the letter O was misinterpreted as a zero in the scientific literature and, once the media and the public noticed the name, Dugas was demonized, mistakenly identified as “patient zero” of the AIDS epidemic.

In the seminal book on the AIDS crisis, “And The Band Played On,” Dugas is referenced extensively and referred to as a “sociopath” with multiple sexual partners. In 1987, The New York Post called him “the man who gave us AIDS” on its front page.

Dugas died in 1984 of AIDS-related complications and now, more than 30 years later, scientists have used samples of his blood to clear his name. Research, published in the journal Nature in 2016, provided strong evidence that the virus emerged in the U.S. from a pre-existing Caribbean epidemic in or around 1970.

“We were quite annoyed by that (‘patient zero’), because it was just simply wrong, but this doesn’t stop people from saying it, because it’s so appealing,” Dr. James Curran, dean of Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health and co-director of the university’s Centre for AIDS Research, told CNN.

1) The outbreak: Typhoid fever

The (possible) patient zero: Typhoid Mary (a.k.a. Mary Mallon)

The viral story: When the conversation turns to patients zero, one name stands above all others — Mary Mallon, better known as “Typhoid Mary.” Her story has had such a long-lasting impact on popular culture that her nickname has become a colloquial term for anyone who, knowingly or not, spreads disease or some other undesirable thing.

Mallon earned her demonizing epithet because she was famously the index case — the first documented — for an outbreak of typhoid fever in New York in 1906. Some believe she was a so-called “super-spreader” before the term existed.

Originally from Ireland, Mallon emigrated to the U.S., where she began working for rich families as a cook. After clusters of typhoid cases among wealthy families in New York, doctors traced the outbreak to Mallon.

Soon after her meals were served, members of the households where she worked developed typhoid fever, a life-threatening illness caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi. As more households where she worked developed typhoid fever, Mallon was soon identified as something of a patient zero, even though she never developed the symptoms.

“There are these individuals, like so-called Typhoid Mary, who for one reason or another may be infected with a pathogen and not have that many symptoms but can shed that pathogen in a way that makes it infectious to other people,” Thomas Friedrich, an associate professor of pathobiological sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, told CNN.

She was believed to have infected 53 people with the virus, three of whom died. Mallon was forced into quarantine on two occasions for a total of 26 years, during which she unsuccessfully sued New York’s health department, saying she didn’t feel sick and therefore could not infect other people.

She died in 1938, vilified in folk memory as “the most dangerous woman in America,” a woman forever known as a patient zero, whether that was true or not.

doug.speirs@freepress.mb.ca