‘The bogeyman’ and developing darkness in Sunny St. James Former friends, teammates of Graham James recall odd behaviour, but nothing to portend depravity to come

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/12/2020 (1825 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

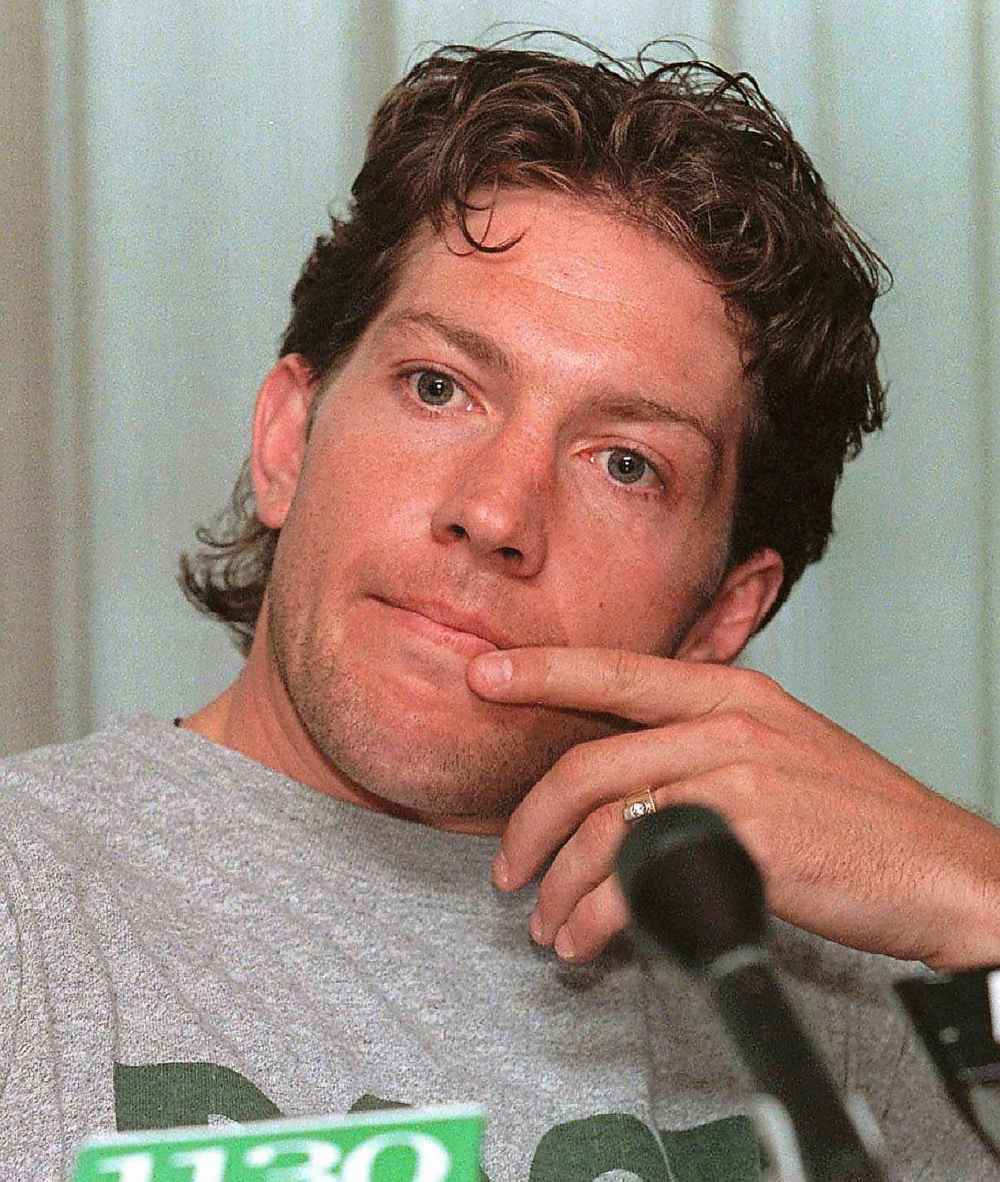

It was midway through Sheldon Kennedy’s seventh NHL season, and the Calgary newspapers were calling for his head.

After discovering Kennedy had collapsed into tears and was unable to suit up for the Calgary Flames’ April 8, 1996 game against the Edmonton Oilers, they published stories he had suffered a nervous breakdown.

About this series

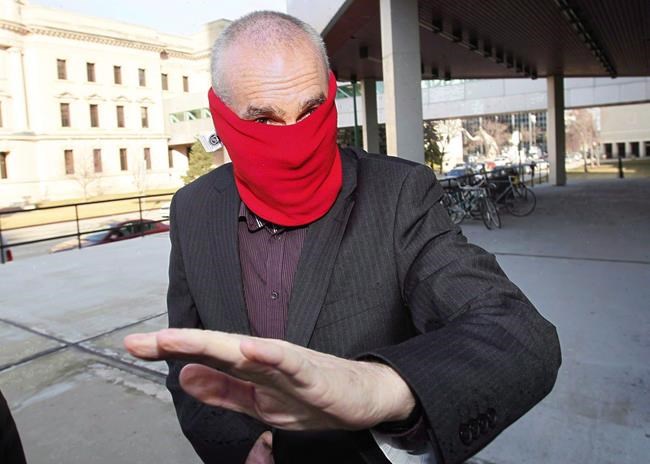

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

While a significant number of the assaults occurred in Saskatchewan, where he coached both the Western Hockey League’s Moose Jaw Warriors and Swift Current Broncos, the James scandal has always been a Winnipeg story.

James worked his way up through the ranks here — in Winnipeg minor hockey, the Manitoba Junior Hockey League and the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors.

It was with this backdrop that Free Press sports writer Jeff Hamilton began investigating James’ past, from his formative years growing up as an Air Force brat in St. James to his time as a substitute teacher in the St. James-Assiniboia School Division, and from his first foray into coaching minor hockey to his ultimate downfall.

Hamilton interviewed dozens of former players, childhood friends, educators and hockey colleagues and officials.

His investigation reveals an awkward teen who found confidence both in the classroom and at the rink, one that enabled him to embark on his trail of destructive criminal behaviour.

The investigation also paints a picture of complicity or, at the very least, wilful ignorance through all levels of the sport, which allowed James to abuse young players for years.

In total, James has been convicted of sexually assaulting five former players: Sheldon Kennedy, Theoren Fleury and Todd Holt have all publicly shared their ordeals; the identities of two others have been protected by publication bans.

However, police estimate the true number of victims is between 25 and 100.

While powerful institutions, such as the Catholic Church, and prominent individuals, including Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, have all had their moments of reckoning, there has been no equivalent to the #MeToo movement in hockey.

This Free Press investigation attempts to change that narrative by giving voice to victims and asking questions of those who knew or ought to have known what was happening on their watch.

Read the full six-part series, titled A Stain on Our Game.

The reports weren’t wrong. Kennedy was unravelling by the second, drinking and abusing drugs to dampen the pain of a dark secret. That night, at home, he emptied a box of Kleenex as tears streamed down his face.

Kennedy and his wife Jana had recently welcomed their newborn daughter, Ryan, into the world. With a new life to take care of, Kennedy could no longer live a lie.

After years of harming himself and those around him, and with Jana fearing the worst was yet to come, Kennedy broke his silence. He told her he had been sexually abused by his junior hockey coach.

“Graham?” Jana asked. Kennedy just nodded.

It became a moment of reckoning for Canada’s game, sending shock waves across the country — through boardrooms of national and provincial governing bodies, city arenas and small-town rinks. With it came a promise to better protect young athletes.

In the years that followed, Kennedy would tell the same story again and again: how he was sexually assaulted by Graham James, his longtime mentor and hockey coach, shortly after being recruited as a skilled and speedy 14-year-old forward from the small western Manitoba town of Elkhorn. How the abuse lasted for years, escalating over time and only ending once Kennedy began his pro hockey career.

James ultimately admitted to his crimes. In January 1997, just days before his 45th birthday, he pleaded guilty to 350 incidents of sexual abuse against Kennedy and an unnamed player; he’d coached both on the Western Hockey League’s Swift Current Broncos in the 1980s and early ’90s.

For those living outside hockey circles, the coach had existed in relative obscurity. But once Kennedy stepped into the spotlight, James became a household name, putting a face on a monster many believed lurked only in the shadows.

Just over a decade later, James would again be in court, pleading guilty to sexually abusing two of his other players — former NHL star Theoren Fleury and Fleury’s cousin, Todd Holt.

The Hockey News had once named James “Hockey Man of the Year” after leading the Broncos to a Memorial Cup championship in 1989. But after being charged, convicted and sentenced to years in prison, he had a more sinister title.

“Mr. James stands before you today as possibly the most hated man in Canada, certainly the most hated man in hockey,” defence lawyer Evan Roitenberg said at the Winnipeg sentencing hearing in 2012 for the assaults on Fleury and Holt.

“He has become the bogeyman.”

If anything was as consistent as James’ predatory tendencies — how he mentally manipulated his victims into feeling powerless and instilled fear of speaking out — it was how he handled the court process each time he was caught: with a plea bargain.

In 2012, the decision to plead guilty was framed by James’ lawyer as a significant gesture on his behalf, aimed at eliminating any further embarrassment for Fleury and Holt, who might find it difficult to testify in open court.

Because James negotiated a deal behind closed doors, he not only spared himself the shame of going through a highly publicized trial, he also eliminated the best chance for a thorough dissection of his behaviour.

So while it has been decades since James was first sentenced for his crimes and years since he was paroled from prison, questions still remain: do we really know who James was and what drove him to years of abuse? And was there anyone he might have crossed paths with who could have influenced his predatory tendencies?

Part 2 of a Free Press investigation uncovered answers to these questions.

David Beer first remembers meeting James when he was 12 or 13 years old. Both of their fathers were members of the Royal Canadian Air Force and had moved their families to Winnipeg in the mid-1960s.

They were in the same Grade 7 class at Golden Gate Junior High, a school in the St. James division and one a short distance from the RCAF 17 Wing base where both boys’ parents also lived. For years, Beer and James would walk to school together.

“We were really close. My family knew him well,” Beer, a 37-year veteran of the RCMP who now does police consulting for a private firm, says over the phone from his Windsor, Ont., home.

“We had a very normal relationship. It stayed that way until the later years of high school, when I started to play junior hockey and we sort of went our separate ways. We weren’t intentionally distant, it just kind of worked out that way.”

Beer says they became fast friends. The bond was, in part, the result of military life. As Air Force brats, it was sometimes difficult to feel a sense of belonging because families could be transferred with little notice. Don James’ family moved multiple times over his career, with the first post in Summerside, P.E.I., where Graham was born, followed by stints in Portage la Prairie, CFB Borden, Ont., Winnipeg and Chatham, Ont.

Beer and James also shared a lot of the same interests, including a love of hockey. They played on the same minor-league teams in the early stages of their friendship, honing their skills at Westwin Community Centre’s outdoor rink.

“I was a hockey fan but he was a hockey fanatic.”

“I was a hockey fan but he was a hockey fanatic,” Beer says. “Like, at 13 years old he could quote you chapter and verse the history of the Montreal Canadiens, back 50 years, before guys I was even interested in.

“Graham was a voracious reader of sports magazines. His four major sporting distractions were hockey, baseball — he was a Boston Red Sox fan through and through — boxing and wrestling. And I mean the goofy kind of wrestling.”

Beer recalls James being a good athlete growing up but, because of his asthma, he struggled with endurance. “He lived with these two inhalers,” he says. Still, James was involved in many sports as a kid and was a constant presence whenever there was a community pickup game.

James’ passion for learning extended beyond sports. He displayed a level of intellectual maturity beyond his years, Beer says. James’ interests in school were English and history and a somewhat-odd desire to stay up on Canadian politics.

“One of the very early things that Graham and I did together — as strange as this sounds — is we went to a Liberal breakfast fundraiser,” Beer says. “Here we are, two teenagers in the mid-’60s, attending a political breakfast.”

James’ uncle on his mother’s side, Charles MacArthur, had a long connection to the Liberal party. MacArthur represented the electoral districts of Inverness North and Inverness in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1988 to 1998 as a Liberal. James’ mother, Rachel, also had a deep interest in politics and had later worked as a constituency assistant for Nova Scotia Liberal MLA Dr. Jim Smith (Dartmouth East).

When news broke James had been convicted of sexually assaulting former players, Beer says he struggled to make sense of what happened. He had been years removed from any meaningful contact with James, having last seen him a decade before, in Regina, where Beer was stationed in the mid-1980s.

James, who was the head coach of the WHL’s Moose Jaw Warriors, was in town scouting the Regina Pats ahead of their game later that week. Beer watched the game with James, who was accompanied by a number of young prospects, including Fleury.

“They were following the coach around like he would expect them to,” Beer says. “In retrospect, it was pretty weird.”

Hindsight is one of the few tools Beer is left with when trying to put the pieces together about what went wrong with his old friend.

“He was fighting some demon, for sure.”

There is one incident that sticks out above the rest. The two were rooming together during an out-of-town hockey trip shortly after they became friends. Beer was asleep in his bed, when James created a ruckus on the other side of the room.

“Graham started to have a ferocious nightmare — just a crazy, crazy nightmare,” Beer says. “He was screaming and yelling and was just outside of himself, to the point you couldn’t wake him up. It was something out of a Hollywood movie.”

James was so overcome that he started to smash his arm against the headboard, his fist eventually breaking through the arborite panel.

“It wasn’t until after he was bleeding all over the place and had smashed the headboard that I got him to wake up,” Beer says. “He was in a cast for about a year afterwards.”

James ended up mangling his hand and was left temporarily disabled as a result. He had cut through the tendons of his middle finger and was forced to undergo multiple surgeries.

Beer remembers talking with James about the incident but can’t recall getting a clear explanation as to why he had suffered such a traumatic episode in his sleep.

“He was yelling and screaming,” he says. “He was fighting some demon, for sure.”

During James’ sentencing hearing for the assaults against Fleury and Holt, his defence team submitted a report that included details of an interview a Montreal forensic psychologist had conducted with their client, meant to shed light on his past.

“He describes his teen years as quiet because he was not interested in partying at all,” the doctor wrote. “He became aware of this difference. He understood that, unlike his companions, he was neither interested in drinking or in girls. For these reasons, even if he was extremely active in sports, he was not comfortable on this social level.”

James was a lean and lanky teenager, with a long face and large nose that resembled Ichabod Crane, the fictional character from Washington Irving’s short story, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

He went by the nickname “Bones” because of his skinny stature. It’s an image that’s in stark contrast to what many might picture now when thinking of James. As an adult coach, James was as well known for his pot-belly stomach, which often protruded from the bottom of his shirt, as he was for his ability to craft a meaningful quote to a reporter.

“We used to joke about him being an eating machine. It was like he had two hollow legs,” says Mike Gazley who, like Beer, was another close high school friend.

“I hadn’t seen him in years when I saw the video of him, the one where he’s taking off his jacket (in a fit of rage on the bench) and his shirt or whatever. I just laughed because, of course, that guy had a big belly.”

Because he was unattractive, along with his seemingly weak frame, James became a target for bullies. For years, he had to defend himself from peers who roughed him up. The constant punishment, his friends say, was rarely warranted.

“Graham was pleasant to everyone and he was easy to get along with,” Beer says. “He didn’t have a mean bone in his body.”

“Word eventually got around that you didn’t screw with Graham.”

Still, there was a limit to the abuse he was willing to endure. Once pushed over the edge, his temper took over. And though he didn’t necessarily look the part, James was tough and fearless, Beer says.

“Word eventually got around that you didn’t screw with Graham. He didn’t go looking for trouble, but he never backed away from it.”

Beer recalls a time when they were playing flag football against other neighbourhood kids. Beer had worn what he described as a “goofy shirt” and his opponents took exception, teasing him on the playground. One thing led to another, and “Graham blew up.”

“All of a sudden the two of us are fighting these three guys,” Beer says. “We got crazy and we actually chased one guy home and Graham chased him into his house and beat the snot out of him, right in front of his mother. He was not going to be denied.”

Beer often saw confidence from his friend, despite his claims to have been uncomfortable in social settings. And he didn’t seem to care what others thought about him.

To drive home his point, Beer says the two decided to carry briefcases in middle school. While Beer, tired of his classmates’ abuse, lasted one day, James proudly kept on.

“He used his for years, up until Grade 10,” Beer says.

In speaking with a number of James’ childhood friends, some of whom asked not to be identified because they didn’t want to be connected to him now, the thing they appreciated most about him was his sense of loyalty.

“Dave and I both would have considered him a super-close friend who would have done anything for us,” Gazley says in a phone interview from B.C.

“He wouldn’t deflect responsibility onto other people,” adds Beer. “He wouldn’t leave anybody else out under the bus, just to protect himself.”

Graham Michael James was born on Feb. 7, 1952, in Summerside, P.E.I., to Don and Rachel James. He is the eldest of four children, with a sister and twin brothers. His mother died in 2015. His elderly father is still alive.

James spent much of his childhood on the East Coast. He was 13 when he arrived in Winnipeg.

In the 2012 forensic report, James described being raised by a “loving and close-knit family.” His friends closest to him paint a different picture.

“His dad was a bit of a violent sort, to be honest with you,” Beer says. “Graham feared him, like physically feared him. I was afraid of him. He just wasn’t a very pleasant guy.”

Gazley echoes much of the same sentiment. As their group of friends got older and started to earn more freedom, James didn’t have the same luxury, he says.

“He wouldn’t socialize as much as we did and he probably didn’t misbehave in some of the ways we did either because of his concerns of being caught,” Gazley says. “If we were out later than we should have been we knew we might get a word or two from our parents and Graham definitely would have been more concerned about that.”

Despite James’ fear of his father, neither Beer nor Gazley witnessed any physical abuse. It was also something they didn’t talk about.

What was clear to them was James’ father took little interest in his son’s sports. Beer says he never once saw him attend a single sporting event, even though his son played on several teams.

“Once in a blue moon we’d see Graham’s dad,” was how Gazley described it.

Beer says James’ mother was warm and caring, but doesn’t recall seeing her at sporting events, either. She would have had her hands full taking care of young twin boys, making it difficult to leave the house, he says.

That left James’ father with a lot of pressure to provide for the family, Beer says, adding that with a wife and four kids it would have been difficult to do on a non-commissioned officer’s salary.

To earn extra income, Don James ran the theatre at the base. He was the projectionist, but had other duties, including cleaning up at the end of the night. James’ mother would sometimes handle the cash register.

James and Beer would often tag along and help out on Sunday afternoons.

“(His dad) was just a guy who was never in a good frame of mind,” Beer recalls. “I can’t remember a single incident of where I saw the guy laugh.”

If James wanted to escape, he would isolate himself in the only place he could. Living in a three-bedroom townhouse in row housing, Graham was confined to a room in an unfinished basement.

“That was his escape,” Beer says.

Rusty James, James’ younger brother by nine years, didn’t have a close relationship with James until he turned 18 and would travel to visit him in Winnipeg for the summer. The family had moved to New Brunswick when Rusty was 10, and the only time he’d see his brother was when he returned to spend a few weeks with the family.

“My dad was Armed Forces and he worked his ass off both at work and afterwards — he always had projects,” Rusty says in a phone interview from his home in Buffalo, N.Y.

“He was tough, in a rules kind of way. You had supper at 4:30 and you didn’t want to be late. You ate all your food or you sat there until it evaporated.”

Although life back then remains blurry, Rusty thought it was unfair to suggest his father wasn’t interested in his kids’ sports. He recalls the family driving in their 1968 Dodge Polara and freezing their butts off, watching Graham play hockey. He also remembers his father hauling him to the outdoor rinks and holding him upside down to thaw out his frozen feet between periods.

As far as toughness, Rusty says that was just part of growing up in the 1970s.

“Do I have recollections of getting my ass kicked a few times by my dad? I do,” he says. “If he told me to do something and I didn’t do it I got my ass kicked. There was nothing ever over the line… I would tell you if there was.”

“We just assumed he was just kind of shy and didn’t care that much about girls.”

While James was trying to navigate shaky waters at home, he was also battling with his sexuality. He became aware of his attraction to males while in high school, which he disclosed years later to a psychologist, but never felt comfortable discussing it freely.

“We just assumed he was just kind of shy and didn’t care that much about girls,” Gazley says.

“Sometimes if someone has those inclinations they may make a gesture towards someone they consider a good friend, right? That never happened and certainly, based on the way his dad was, there would be no doubt in my mind that he’d be scared to death to admit any of those feelings to him.”

Beer has spent a lot of time over the years trying to identify if there was someone in James’ life who might have influenced his behaviour. As a former cop, he knows the statistics about predators and the common triggers.

He has no solid proof of anything, just theories. But he can’t help but think that there was something traumatic in his friend’s past.

“It’s something I’ve pondered; what was the root of all this for Graham?” Beer says. “The relationships he had to have cultivated while he was in his late teens, that’s when I would say it must have started. Because I saw nothing and I was with him a lot until then.”

By his late teens, James was running with a different group of friends.

Beer had moved on to play for the St. James Canadians and, with junior A hockey being a significant time commitment, didn’t have room for much else. The same could be said for Gazley, only it was simply a growing number of conflicting interests that led to fewer reasons to catch up.

They still kept semi-regular tabs on their friend and Gazley, who was similar in talent to James on the ice, played on a couple of the same midget hockey teams.

“As I grew older and we sort of grew apart, Graham definitely had a younger group of people that gravitated to him,” Beer says.

James spent a lot of his free time at the Westwin Community Club. He lived a few blocks away and had developed a close relationship with the people maintaining the rinks.

“Of all the outdoor rinks in those days, they probably had the best ice,” Gazley recalls. “If we were going to hang out somewhere, we used to go there. As I recall, Graham had access to the club at funny hours or whatever and probably scraped and flooded the ice at times.”

”Graham definitely had a younger group of people that gravitated to him.”

James was starting to coach younger kids in hockey, while also refereeing the odd game at Westwin. That eventually led to hanging out with players outside of team activities. St. James had evolved into a major hub for hockey talent and James made considerable effort to attach himself to some of the community’s most gifted players.

The Free Press reached out to some of those former players. A few agreed to talk, while others preferred not to or ignored interview requests. Some went on to play professional hockey, including the NHL. All requested anonymity.

“These kids fell into that category of people who started to hang out with him after they had played hockey for him,” Beer says. “I often wondered if any of these kids were victims of his at one time.”

“I often wondered if any of these kids were victims of his at one time.”

Many stories about James from his teenage years have survived the test of time. How he used to meticulously study the people around him, sometimes in extreme detail. According to one person, James would go as far as to dissect the individual’s personality. He would then offer up a list of well-thought-out tips he felt could lead to an improved life.

“He wrote, like, six full pages, in point form, on how you could change your personality and how you could become a better person,” a former acquaintance says. “I just found that to be so Graham.”

Other stories included James sitting outside the homes of players in the early morning, waiting, in some cases for hours, until they opened the door. His obsession with young players evolved to writing scouting reports, where he outlined their strengths and weaknesses.

“He would just latch onto these guys,” a high school classmate says. “But never did I hear about anything sexual.”

Though James started to turn his focus to coaching near the end of high school, he continued to play hockey, too. It would be during his juvenile season, months after his high school graduation in 1971, when he crossed paths with a coach by the name of John Charles Nelson.

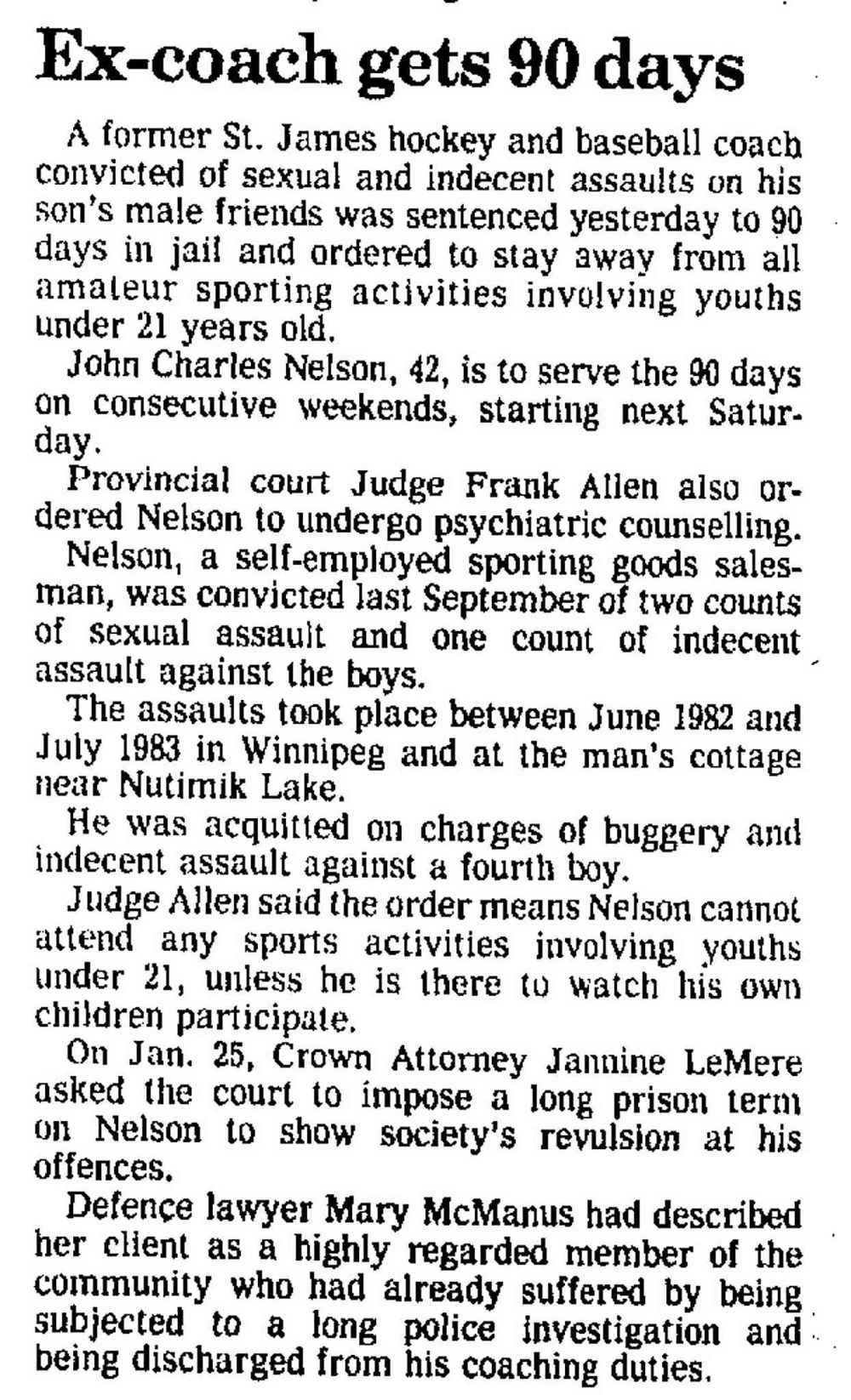

Nelson, who went by Jack, coached hockey and baseball in St. James, volunteering at various community clubs for more than a decade. All that came to a crashing halt in 1984 when Nelson was convicted of sexual and indecent assaults on his son’s male friends, two of whom were 14 and the other, 13.

Nelson, 42 at the time, was originally sentenced to 90 days behind bars. The term was increased to 15 months after a successful appeal by the Crown. Nelson died in 1994.

James would sometimes tag along with Nelson during his workday, which included helping him fill coffee machines across the city.

In his 2012 sit-down with the forensic psychologist, James claimed he had never been physically or sexually abused. And in response to Free Press questions sent to a longtime hockey friend who agreed to act as an intermediary, James said that although he could understand people thinking there might have been something between the two, given how much time they spent together, he has “nothing negative to say about Jack Nelson.”

But there are some who knew both James and Nelson who wonder what role he might have played in James’ future behaviour.

“There’s another part to Graham’s story and it’s about what happened to him, how he was in a prime position to be groomed,” says a former friend who also played for Nelson. “He was always the odd guy out, and coaches — or at least one coach, Nelson —recognized that.”

“He was always the odd guy out, and coaches… recognized that.”

Nelson, who was overweight and had slicked-back black hair, didn’t look like an athlete. He had an old-school approach to coaching, relying on aggression and fear to get the most out of his players.

“It was the first time I ever had a coach that literally taught us to fight. He would have us dropping the gloves on the ice in practice,” says Bryon Benn, who was also coached by Nelson in the early ’70s.

“He was just really aggressive with the guys on the ice. He was a yeller and you could say he wanted us to play an old-school brand of hockey. It was pretty rough.”

Benn doesn’t remember an unusual connection between James and Nelson. It’s been five decades since he’s seen either of them, so his memory is foggy. Still, he says he doubts he would have been looking for that connection, anyway.

The only thing that sticks out to Benn was an incident during a hockey trip to Dryden. He and a few friends were sitting at a table and James was sleeping in the bed on the other side of the room.

“A bunch of us were sitting around and drinking beer and Graham was in bed already,” says Benn, recounting an event eerily similar to one described by Beer that occurred years earlier. “Next thing I know, he’s up and he’s pounding the headboard of the bed with his fist. The headboard just splintered when he put his hand through it.”

”I was always leery of him… He was just a strange character to me.”

Benn adds Nelson used to have the team over to his house for parties, where he would provide alcohol, even though many of the players were underage. He says Nelson never tried anything sexual on him, nor had he heard of anything untoward happening to anyone else.

Still, he had his own reservations.

“I was always leery of him,” Benn says. “He was just a strange character to me.”

Others weren’t as diplomatic.

“He was a complete lunatic,” says another former Nelson player. “How he was ever allowed to be around children is beyond me.”

The player, who requested anonymity, described a more troubling setting at Nelson’s home where he would invite players over to lift weights.

He went just once, but his first red flag was the pornographic magazines strewn across a table. He knew it was time to leave when Nelson began to ask guys to take their shirts off so he could see the definition forming on their muscles, which glistened as he rubbed their bodies down with oil.

“I’m thinking to myself, ‘this is f–king lunacy,’” he says. “Some kids stayed, like Graham. They thought it was pretty cool.”

“How he was ever allowed to be around children is beyond me.”

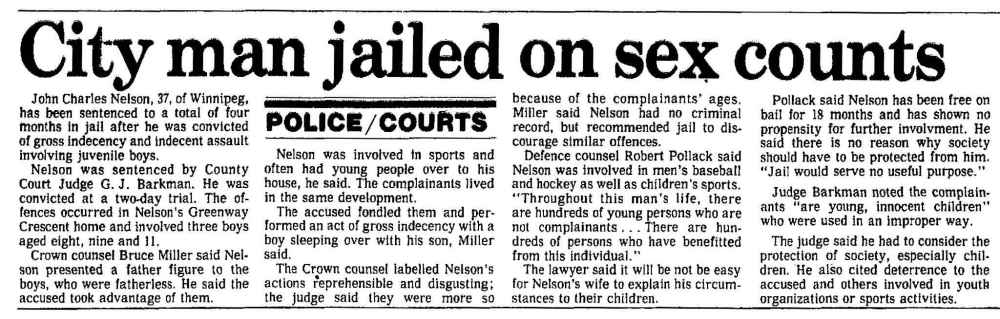

When Nelson went to jail in 1985, it wasn’t the first time he faced criminal charges.

In February 1980, he was sentenced to four months behind bars after being convicted of indecent assault on three boys — age eight, nine and 11 — at his home on Greenway Crescent. The children lived in the same housing development and the incidents occurred at night, during a sleepover.

During the trial, the Crown argued Nelson presented a father figure to the boys, who didn’t have one at home, and that he took advantage of their family situation. The verdict was overturned after the Court of Appeal ruled the sentencing judge put too much weight on the testimony of the boys, who did not fully understand the nature of the oath they took.

While it can be standard practice for predators to befriend their victims, acting as a parental figure, it’s difficult to ignore the similarities between Nelson and James.

During James’ 2012 sentencing, the Crown presented its own expert’s findings based on court transcripts, victim-impact statements, police reports and interviews with several prominent members in the hockey community who knew James.

The report, in part, reads: “The victims he targeted were boys who he perceived as being disadvantaged and would step into a parental role.”

James, like Nelson, preyed on his victims during the middle of the night. In the case of Kennedy, Fleury and Holt, the first incident of abuse occurred while the victims were asleep, only to be awoken by James groping them.

What is most troubling, though, is that James’ earliest sexual assault charge was not against Kennedy, but towards an unnamed 14-year-old in 1971. He pleaded guilty to a charge of indecent assault on Feb. 27, 1998, a year into his 3 1/2-year sentence for his crimes against Kennedy. He received a six-month concurrent sentence.

James would have been 19 when the assault was committed, the same time he and Nelson were forming a close friendship.

“I am not a victim,” James says, speaking through his friend. “I made some terribly wrong decisions and I have to live with the consequences.”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

After a slew of injuries playing hockey that included breaks to the wrist, arm, and collar bone; a tear of the medial collateral ligament in both knees; as well as a collapsed lung, Jeff figured it was a good idea to take his interest in sports off the ice and in to the classroom.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, December 14, 2020 9:46 PM CST: Updates bio info