Fear factor Researchers racing to stay ahead of inevitable oil spill that will foul pristine northern waters as disappearing sea ice invites shipping, cruising traffic

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/10/2020 (1865 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A threat is looming large as Arctic sea ice continues to deteriorate: industrial accidents, such as oil spills, soon overtaking the pristine waters and sensitive ecosystems of the North.

Led by scientists at the University of Manitoba, researchers from across Canada are looking to expand knowledge on how to deal with these types of calamities. Research will soon get underway at the newly completed Churchill Marine Observatory, a white dome building on the shore of the Churchill River.

“As the Arctic opens up, there’s more and more opportunity for transport through the Arctic, and not just industry but there’s… more cruise ships that can make their way through the Arctic. So ship traffic in general, is increasing, which therefore leads to the potential for greater accidents,” says Gary Stern, chair of the CMO’s board of directors.

Stern, a research professor at the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Earth Observation Science, studies Arctic marine and freshwater ecosystems. With the possibility of an ice-free summer in the Arctic in the near future, understanding how oil behaves in an Arctic ecosystem is critical, he says.

“What would happen to oil under sea ice? What normally happens when it’s on the surface or under thin ice, is that the more volatile compounds of (the fuels) would go up into the atmosphere, and some of the remaining compounds would be degraded over time by bacteria and other things,” he says.

“But what happens when it’s trapped under the ice? None of that happens, it’s like putting the cap on a bottle.”

The research facility has been more than a decade in the making; it gained traction in 2014 when it was first matched with some government funds. The CMO consists of four key research features.

First, there is the “Ocean-Sea Ice Mesocosm” or the OSIM, which is located in CMO building on the shores of the Churchill River. The OSIM is made up of two pools that will be filled with water directly from Hudson Bay and will be used to simulate experiments in a controlled environment. The building’s retractable roof and controlled heating will allow researchers to play at will with different aspects of the marine environment.

The research will look at how to detect oil and how to address spills, should they occur.

“As the Arctic opens up, there’s more and more opportunity for transport through the Arctic, and not just industry but there’s… more cruise ships that can make their way through the Arctic. So ship traffic in general, is increasing, which therefore leads to the potential for greater accidents.”

– Gary Stern, chair of the Churchill Marine Observatory’s board of directors.

A second feature is an environmental observing system, which consists of a series of instruments strung out into the Churchill River estuary on taut-line moorings, with a similar setup established in the shipping channel across Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait. The observation system allows for a better understanding of everything from water chemistry to noise levels to ice movement in the area, so research at the OSIM can reflect current circumstances in the Canadian Arctic.

In operation for two years already, the CMO also has access to the research vessel William Kennedy, which is a former fishing boat that’s been outfitted with millions of dollars of oceanographic equipment to allow for Arctic science expeditions. The third season of research was cancelled this summer because of the pandemic.

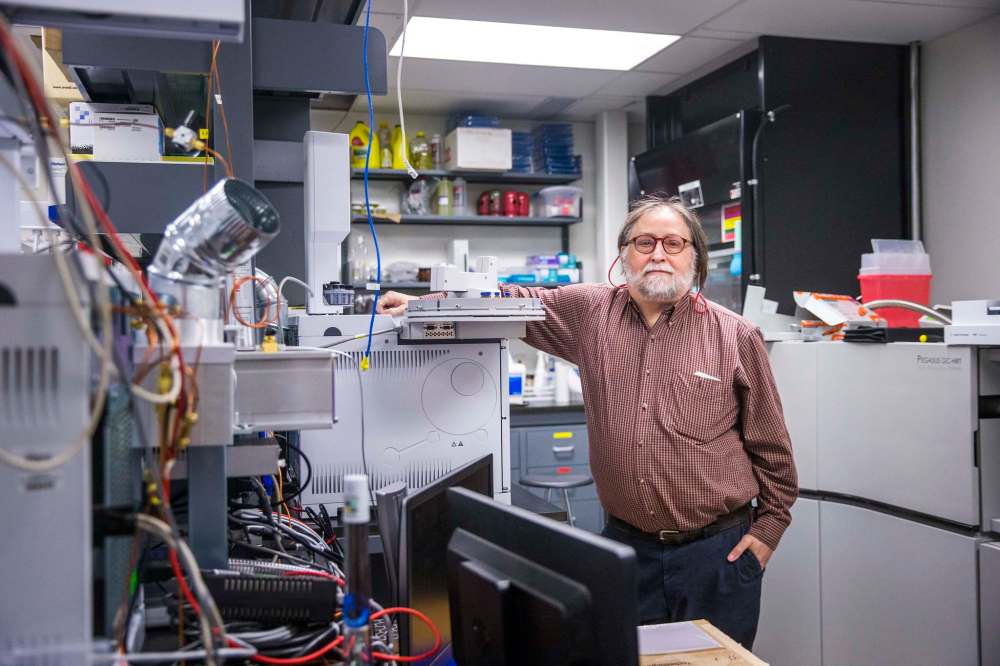

Fourth, the Petroleum Environmental Research Laboratory was established at the University of Manitoba, led by Stern, to conduct the more complicated scientific analyses that can’t be done at the facilities in the North.

Stern says this research is needed now, not in the future. Last spring, the largest recorded Arctic oil spill happened in Russia, when 21,000 tonnes of diesel fuel leaked into a river within the Arctic Circle near the Siberian city of Norilsk.

“There’s all sorts of studies in the Gulf of Mexico and other places,” he says. “But there’s very few studies that have gone on that can actually try to emulate what would happen in the sea-ice environment if there was a spill.”

To underscore the sense of urgency, Stern says the equivalent area of Lake Superior is being lost in Arctic sea ice every year.

“But it’s not just the sea-ice extent, it’s also the type of sea ice. Ice in Hudson Bay, we call it annual ice or first-year ice, because it forms in the winter time and melts completely in the summer. But in the higher Arctic, at the higher latitudes, it doesn’t always completely melt.… And we call that multi-year ice and it’s very different from first-year ice, in terms of its salinity, brine volume and all these other things. So we’ve lost a lot of that multi-year ice, comparing it to the ‘70s, we’ve lost about 80 per cent,” he says.

And now weather patterns are changing as a result of that shift, Stern explains, the same way weather patterns would change if you cut down all the trees in a rainforest.

“And because we’re losing all that sea ice, it makes it easier for ships to transport in and out of the Arctic,” he says. “Instead of having to go through the Panama Canal, they could go through the Northwest Passage and that would save them huge amounts of money and fuel and time.”

● ● ●

Some Canadian politicians are eyeing the melting sea ice with a different point of view: economic opportunity. In February, Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe resurfaced the idea of building a crude-oil pipeline to northern Manitoba to ship fossil fuels through the Arctic. The Saskatchewan Party also has a 10-year economic plan that includes “supporting efforts to export oil by tanker through the Port of Churchill.”

Days later, Manitoba’s premier said it wasn’t an idea he would shy away from.

“The previous NDP government dismissed the very idea of shipping oil products out of Churchill out of hand, without even looking at it,” Brian Pallister said.

“We’re very, very big on northern development and I’m very, very committed to working in partnership with affected people in northern Manitoba — including First Nations and Métis people — to make sure that we find great job opportunities and economic development opportunities for northern communities.”

“The previous NDP government dismissed the very idea of shipping oil products out of Churchill out of hand, without even looking at it.”

– Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister

In 2014, OmniTrax, the previous owner of the Port of Churchill and the northern Manitoba rail line, suspended its pursuit of shipping oil through the port due to substantial opposition from environmental and Indigenous groups and some members of the provincial government.

For current owner Arctic Gateway Group, the possibility of shipping oil through the port has not been ruled out, but it is not a prospect being actively pursued.

“It’s an idea that will definitely be for consideration and talked about in the future. We’ve seen what’s happening with oil and how it’s getting landlocked,” says Opaskwayak Cree Nation Chief Christian Sinclair, who sits on the board of directors for AGG.

This is one of the benefits of 50 per cent of AGG owned by northern community stakeholders; it means no decisions will be made without extensive consultation with Indigenous groups in the region, Sinclair says.

Churchill Mayor and AGG board member Mike Spence says there aren’t enough details currently being advanced to even consider a pipeline a viable option.

“First of all, we’ve got to understand what that means,” he says, but adding that all legitimate proposals need to be considered in order for his community to succeed.

“Being a port community, you’re going to get that kind of door-knocking,” he says.

Niki Ashton, NDP MP for Churchill-Keewatinook Aski, says the idea of running a pipeline to Churchill is a non-starter, as will be any proposal that doesn’t properly consider the risk to the unique ecosystems of the region.

“What people here want is not unlike what people anywhere want, which is opportunities for gainful employment, gainful work so they can support their families, so they can support their community. And oil is not that.”

– Niki Ashton, NDP MP for Churchill-Keewatinook Aski

“We have to be very clear about how potentially destructive an oil spill could be,” Ashton says, emphasizing the need to protect both wildlife and the livelihoods of the people — primarily Indigenous community members — who depend on the region’s ecosystems.

“What people here want is not unlike what people anywhere want, which is opportunities for gainful employment, gainful work so they can support their families, so they can support their community. And oil is not that.

“Pushing oil through northern Manitoba is not going to create the gainful opportunities for northern Manitobans. People know that, and if anything, it’s extremely dangerous for our part of the country.”

Ashton says there’s opportunity to invest in infrastructure in the North that helps to battle climate change instead of investing in infrastructure that makes the problems worse.

● ● ●

Whether oil is shipped through the Port of Churchill, there is no doubt oil will be moved through the Arctic in higher quantities. More industrial activities, such as mining, will also increase the risk to water systems.

Stern is working closely with the Canadian Coast Guard, which is desperate for “tools in their toolbox” for dealing with the possibility.

“Because, right now, it’s illegal, for example, to add deleterious substances to the water,” preventing the deployment of some of the possible mitigating chemicals that have been deployed in other spills, Stern says.

Or in some circumstances, spilled fuels are ignited in a process known as in situ burning, in order to eliminate most of the oil from the ecosystem.

“Right now, I’m not sure that we could actually get permission to do situ burning in the Arctic, just because there haven’t been enough studies to show what the ramifications of that are,” he says.

The U.S. Coast Guard, in concert with the American National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is working on the same problem off the coast of Alaska.

The Arctic Council released a report in the spring of 2020 that noted a 25 per cent increase in traffic through the Arctic between 2013 and 2019, with the total distance sailed by ships in the region growing by 75 per cent. Although most of the vessels were fishing boats, in 2019 there were also 73 cruise ships.

A subsequent report released earlier this month showed that the fuel consumption of those ships operating in the Arctic in the same time frame increased by 82 per cent.

The potential for increased cruise-line traffic is not to be underestimated. In the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, the increase has been jarring, with roughly a 20 per cent increase in cruises per year for more than a decade. Most of the ships run on heavy fuels.

And then there is also an increased interest in oil and gas exploration in the Arctic. In 2008, it was estimated that the Arctic held 13 per cent of the world’s undiscovered oil reserves and 30 per cent of undiscovered natural gas.

Meanwhile, Russian mining company Nornickel, which owned the storage tanks involved in the massive diesel spill, has cleaned up the area, to some extent. But researchers believe that the spill will have lasting effects in the pristine northern ecosystem for years to come.

sarah.lawrynuik@freepress.mb.ca