Building on power of spirituality, tradition

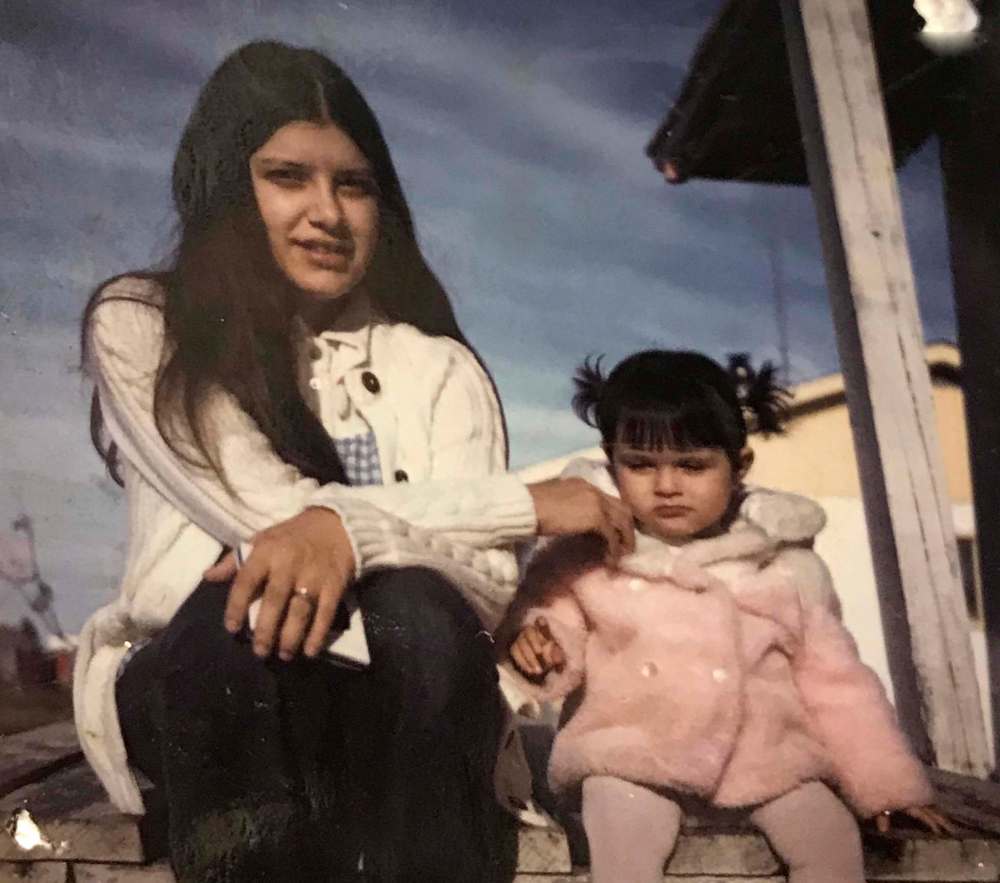

Orianna Courchene, 66, helped found renowned Turtle Lodge, Indigenous women's ceremony

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/09/2020 (1902 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The smell of cedar was strong during that first full moon in May.

By a little lodge built of tamarack wood and dressed with symbolic red cloth, a group of about 25 women weaved piles of cedar leaves into beds. For four days and four nights in Sagkeeng First Nation, they camped outside and cooked over the open fire, keeping a watchful eye on each other’s children. They feasted on sturgeon, duck, game, potatoes, corn on the cob; and wild rice with blueberries and maple syrup — Orianna Courchene’s special recipe.

Courchene was dressed in vibrant green — a ceremonial dress she’d sewn herself, with a pattern of delicate strawberries clustered from ankles to chest. Even the fabric was symbolic; blood-red and heart-shaped, the strawberry signified womanhood. Courchene knew the fruit was considered cleansing when used in traditional Indigenous medicines; the vine-like runners were seen as a natural representation of mothers’ connections to children and extended families.

Eagle staff in hand, Courchene turned the group’s attention to the grandmothers asked to speak. They sat on the ground in sharing circles, and taught the younger women about connections to the land surrounding them. They talked openly about things that, until then, were whispered in secret, if discussed at all: women’s rites of passage, healthy relationships, responsibilities of motherhood, and self-care, all through the lens of the seven teachings that form the backbone of First Nations spirituality in Manitoba.

That was more than 20 years ago, not far removed from the time when practising Indigenous traditions was forbidden, driven underground and all but buried by colonization.

Courchene was bringing to life a first-of-its-kind women’s gathering, one she called Mother Earth Lodge. It became a regular spiritual ceremony on the grounds of Sagkeeng’s Turtle Lodge International Centre for Indigenous Education and Wellness, which was founded by her husband, Dave Courchene Jr., with her support in 2002.

When she died after illness Feb. 5, three days after her 66th birthday, Courchene left behind what was most important to her: family, including four children, 18 grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren. The way she lived will ripple beyond her family and community, those she inspired say.

“I’m really sorry that she had to go, but she left a legacy,” says Mary Maytwayashing of Lake Manitoba First Nation, who knew Courchene for more than 30 years. “And that legacy has to be carried forward.”

Maytwayashing was at the first Mother Earth Lodge ceremony, and hopes to help revive the practice once COVID-19 pandemic dangers have passed.

“That’s where my healing journey really began, when I sat on the earth and heard the voices… of Orianna, and other women that came together, sharing the other stories from other women, you know, that gave you a lot of strength,” she says.

“I was so happy. It gave me strength, and it gave me a lot of hope. I realized at that time that this is what has been missing for a long, long time for our people — and this was a long time coming.”

Courchene didn’t grow up with the traditional First Nations beliefs she so strongly held for most of her life. She was born Orianna Fenner in Cormorant, and raised in The Pas, the second oldest of seven siblings.

With a paternal grandmother who was Ojibwa but lost her status when she married a non-First Nations man, and a maternal grandmother who was Cree and Métis, Courchene and her siblings were brought up as Métis and attended Christian church services.

Legislative changes would later allow the family to officially regain Ojibwa status, but not until after Courchene had already left home and started her own family in Sagkeeng.

Courchene’s youngest sister, Sharon Wilson, recalls later visiting Orianna and her in-laws. Someone brought up a suitcase teeming with ceremonial clothes from the basement. Soon, all of the children who had been playing in the front yard were having a game of dress-up, decked out in regalia during a time when such things weren’t often put on display.

“To me anyway, it looked like that was the start of a movement, where people started to find their way back to that culture, started to practise it and live it,” Wilson says.

Those were early days of Courchene’s strong, traditional faith. Wilson says it helped her sister the same way it helps a lot of people, of all backgrounds.

“Orianna didn’t have a magical life. She faced things in her family and her life — you can’t have 18 grandchildren and not worry about them and have things happen. But she was strong, she got through all of it, and I believe that her faith probably played a really big part in it.”

Courchene was 17 when she visited a school friend in Sagkeeng and was introduced to the man who would become her husband of 49 years. Orianna and Dave Jr. got married in a matter of weeks after they met in 1971.

Her father-in-law, David Courchene Sr., a member of the Order of Canada, was founder of the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood and the first person elected a grand chief in Manitoba. The young couple soon found themselves at the forefront of another movement — one that saw them build a not-for-profit Turtle Lodge that’s been visited by people across Canada and is now internationally known as a sacred place to practise Indigenous ceremonies.

Dave Jr. is known as a knowledge keeper; Courchene believed she belonged at home with their children and grandkids, being there for whoever needed her. “Without her, I don’t think I’d be sitting here today,” he says.

After the idea for Turtle Lodge came to him in a vision, Dave Jr. decided to quit his job as superintendent of education in Sagkeeng, with his wife’s encouragement.

“I came home, and I said, ‘I’m going to quit. I have a dream.’ She supported me right away. She said, ‘I will be a part of your dream.’ And she followed her commitment all the way through. I think what it did for her is it helped her fulfil her identity, too, and her love that she had for children. There’s so many young women today that were blessed from her mentorship,” Dave Jr. says.

One such woman is filmmaker Lisa Meeches.

“Everything I do as a decision maker today has something to do with her outlook in life,” Meeches says.

They first met during ceremonies at Turtle Lodge, later bonding over health struggles and sharing their faith. Courchene would always sit in the back, listening intently and occasionally whispering a well-timed joke.

“She was the cool kid to hang out with at ceremony,” says Meeches.

“I used to sit in the front with the other elders and the pipe carriers, the knowledge keepers, but then I realized the real knowledge is in the back of the room. She was listening passionately to other people’s hurts and stories and dreams and visions, and wanting our people healthy.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.