Enforcing injustice, keeping the colonial peace The history of Canada's police is rooted in racism and bigotry; Black, Indigenous and people of colour continue to suffer the consequences

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/08/2020 (1934 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

One of Canadiana’s most recognizable images is that of the Mountie: sitting tall on horseback in a bold red coat, high leather boots and pristine beige Stetson, a long-revered symbol of Canadian tolerance, civility and peacekeeping.

The history of Canada’s policing, however, has not been as civil as the imagery would suggest.

In June, the nation watched as dashcam footage showed an RCMP officer tackling Chief Allan Adam of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and punching him repeatedly in the head during a traffic stop. Photos of Adam — bloodied and bruised — circulated in the media against the backdrop of widespread protests against police brutality and systemic racism in policing.

While some Canadians were shocked by the apparently unprovoked violence displayed by the force, Black, Indigenous and other marginalized people throughout the country assert this treatment has existed within RCMP ranks all along.

The histories of Canada’s policing have often been written by the victor, says University of Winnipeg instructor Fadi Ennab.

Studying parliamentary archives in Ottawa, Ennab, whose graduate research centred on the history of Canada’s policing, found the official records of Canadian policing were “not necessarily overtly violent.”

“That’s why some historians have argued that the Canadian frontier is quite peaceful, but the absence of those physical encounters doesn’t mean that it was a peaceful arrangement,” says Ennab.

When confronted with conversations about discriminatory policing, Canada is quick to distinguish itself from the violence seen in the United States, where police are responsible for civilian deaths on a near-daily basis. Protests have reached a peak in recent months, as names like Breonna Taylor, Jacob Blake, and George Floyd have become ubiquitous — providing rallying cry after rallying cry against a culture of violent policing.

Like police across the United States, however, Canada’s national and municipal police agencies were originally designed to aid in the settlement of Indigenous land and make room for white settlers to accrue wealth — often at the expense of marginalized people.

The commonly understood history of Canada’s frontier, Ennab says, presents “the myth of the police officer” as a peaceful, law-keeping force.

“Sometimes they didn’t necessarily use overt physical violence, but they’ve had other ways of controlling movements,” he adds.

It is these histories at the foundation of the mistrustful and often tumultuous relationships between police and marginalized communities today. It is these histories that ignite the cries for abolition, defunding and other dismantling of police forces across Canada and the United States.

PART I: The Origins of Policing

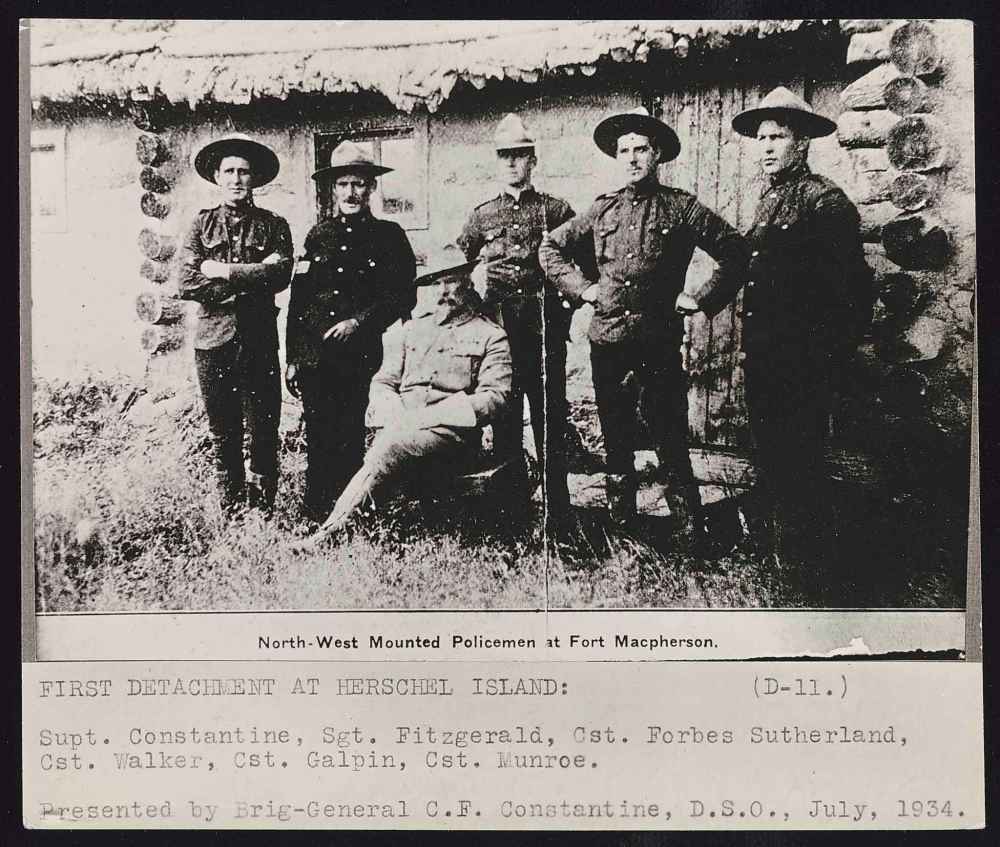

The history of Canada’s national policing begins in Manitoba with the birth of the North-West Mounted Police, the red-coat clad precursor to the RCMP.

As the history books would tell it, the idea for the NWMP was conceived with the sale of Hudson’s Bay Co.-owned Rupert’s Land to the then-Dominion of Canada. Then-prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald was in search of a way to govern the ever-expanding dominion, secure land for the coast-to-coast railway and protect the young nation from its land-hungry neighbour to the south.

Metropolitan police forces, modelled after London’s in the U.K., had already sprung up in eastern cities such as Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City, but as the country’s leaders began to push westward, Macdonald realized a national force was needed.

The Cypress Hills Massacre of June 1873, recognized as one of Canada’s bloodiest mass killings, saw a group of American whisky traders murder a group of Assiniboine in present-day Saskatchewan.

Sensing an opportunity, Macdonald founded the NWMP, ostensibly to protect and defend Indigenous peoples from southern attacks and control the spread of alcohol in the Canadian Prairies.

“Of course, the larger context was the desire to fill the West with white settlers and get Indigenous people out of the way,” University of Manitoba history professor Jarvis Brownlie says.

Ennab says the narrative of whisky traders and American marauders helped to paint the NWMP in the light of a kind of “saviourhood” that would make the police more palatable to Canada’s Indigenous population.

“It’s part of a myth-making: if you control memory, you control public image, you control the future,” he says.

“If we take the word, for example, of Canada’s first prime minister, his wording was that we needed to prevent an ‘Indian war,’ and that’s why we need to establish the mounted police and send them from east to west.”

Macdonald’s determination to establish the NWMP culminated in 1874 when troops were sent to Dufferin in this newly minted province to begin the historic “March West.” For some time, the relationship between the NWMP and First Nations and Métis across the Prairies was calm.

Brownlie notes that while First Nations along the NWMP’s path did not approve of “armed newcomers” on their territory, they appreciated the actions against whisky traders and wanted to make good relations.

While the States were engaged in “Indian Wars,” massacres and extensive violence towards Indigenous populations, Canada’s Mounties were outnumbered, less prone to violence and more inclined to engage in talks and treaties.

“We did have these ideals of peace, order and good government — of being the good guys that didn’t go around murdering Indigenous people and taking their lands by military force,” Brownlie says.

“Now, they didn’t always follow it at all or very well, but that was still a principle: that they wanted to take over the land in a peaceful way.”

.jpg?w=1000)

With time those relationships dissolved. As the government showed reluctance to honour its treaties, Métis and First Nations people began to gather and discuss ways to ensure the treaties would be respected and enacted.

“This is where the Mounties come in,” Brownlie explains. “The NWMP were used to break up gatherings where they were having these discussions, and to force people to move around.”

A pattern quickly emerged: when the government needed to secure land, build railways or quell the voices of Indigenous people asserting their treaty rights, the Mounties would arrive. Tactics of intimidation, harassment and cultural erosion became commonplace as the government expanded its lands and forced Indigenous peoples onto smaller and smaller reserves.

“The government knew exactly what they were trying to do and were determined to do the usual divide-and-rule thing,” says Brownlie.

“The police were used to forcibly drive people out of those areas, to deny them the reserves that they had asked for, to which they had a right under the treaties.”

AN EARLY HISTORY OF POLICING

1834 — Slavery is abolished in the British Empire, including British North America

1835-1864 — First Metropolitan police forces, modelled after Sir Robert Peel’s metropolitan police in London, are formed in Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City, Kingston, Ottawa and Halifax

1855 — Toronto Board of Police Commissioners formed as oversight of the police department

1867 — The British North America Act is signed.

1868 — Hudson’s Bay Co. cedes the West to the Dominion of Canada and the Dominion Police Force is established

1870 — Provincial police forces established in Quebec and Manitoba

1834 — Slavery is abolished in the British Empire, including British North America

1835-1864 — First Metropolitan police forces, modelled after Sir Robert Peel’s metropolitan police in London, are formed in Toronto, Montreal and Quebec City, Kingston, Ottawa and Halifax

1855 — Toronto Board of Police Commissioners formed as oversight of the police department

1867 — The British North America Act is signed.

1868 — Hudson’s Bay Co. cedes the West to the Dominion of Canada and the Dominion Police Force is established

1870 — Provincial police forces established in Quebec and Manitoba

1871 — Provincial police established in British Columbia

1871 -77 — the first seven treaties are signed between Canada and Indigenous nations in the southern plains.

May 1873 — the North-West Mounted Police are founded as a central police force

June 1873 — Cypress Hills Massacre claims the lives of at least 23 Assiniboine people in a clash over missing horses

August 1873 — The first 150 members of the NWMP are sent west to Manitoba

February 1874 — the Winnipeg Police are founded under the leadership of John Ingram

July 1874 — Another 125 members join the NWMP ranks and begin the March West

1876 — the Indian Act is signed, placing restrictions on First Nations land and movement

1882 — Force grows to 500 members as NWMP shift north to quell Métis rebellions

1885 — NWMP are involved in the 1885 Rebellion. Historians disagree on the role the NWMP played in the violence, the force is generally criticized for the part it played

1885 — the Pass System turns several reserves into “open-air prisons.” First Nations are not allowed to leave reserves without express permission from Indian Agents, enforced by police.

1890s — Ongoing criticism of NWMP conduct results in a shrinking of the force

1895 — Cree leader Almighty Voice arrested for stealing a cow, escapes custody and kills officer who tracks him down

1897 — Almighty Voice killed after two-year NWMP manhunt in clash that leaves several dead on both sides

1909 — Ontario Provincial Police founded

1920 — The Dominion Police Force is merged with the now-Royal North-West Mounted Police to form the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Mounties threatened to cut Indigenous women’s hair, pointed cannons at communities, disrupted cultural ceremonies, killed off bison supplies and controlled access to food and land as they cleared the way for settlers.

Physical violence wasn’t necessary, Ennab says, when NWMP could use tactics such as starvation, ration systems and denial of cultural ceremonies to gain control.

“You don’t always have to draw blood to be bloody.”

The NWMP were merged with the early Dominion Police Force in 1920 to create the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, but the change in name did nothing to change the force’s practice.

Through residential schools — the last of which closed in 1996 — and the ‘60s Scoop, where Indigenous children were taken from their families for forced assimilation, the RCMP represented the physical arm of the Canadian government in efforts to silence and suppress Indigenous culture and life.

“They’ve been the enforcement arm of the state in advancing all of these policies that have caused harm to Indigenous people,” Brownlie says.

“And they’re still doing that.”

As the NWMP and RCMP rose as a force to silence Canada’s Indigenous peoples, Canada’s Black population, too, faced over-policing and surveillance.

“The first criminalization of Black people in public space was this assumption that any Black person moving through public space could be what was called a ‘runaway slave,’ a ‘fugitive slave,’” says Robyn Maynard, activist, scholar and author of Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present.

“This is something that was considered criminal by police and also by broader white society that led to highly public notices describing Black people who were considered criminal for the crime of having stolen themselves.”

Canada, long viewed as the gate of freedom for Black people freeing themselves from enslavement in the United States, has its own storied history of slavery.

Enslavement was legal and common throughout Eastern Canada in the 17th century, Maynard explains, and only became less than legal with Britain’s abolition of slavery across all its colonies in 1834.

Abolition, however, did not mean the end of practices of indentured servitude or degradation of Black lives. As slavery remained legal in the United States, Canada’s law enforcement agencies worked to catch and punish formerly enslaved peoples. Incarceration rates for Black men and women began to climb at disproportionate rates.

“The fact is that the earliest kind of policing Black people was precisely about supposedly protecting the property of white slave owners because Black people were considered to be their property,” says Maynard.

As municipal police became commonplace throughout Canada in the 19th century, Black people became overrepresented in jails and arrest records. Black women in particular often faced charges of vagrancy or prostitution, simply for being in public space, Maynard explains.

Between 1864 and 1873, Black women made up three per cent of Halifax’s population, but 40 per cent of those in prison, she explains as an example. In Vancouver, almost 30 per cent of women arrested on morality charges between 1912 and 1917 were Black.

“It’s often talked about in the Canadian media that this is a crisis, the arrests of Black people, what’s called carding or street checks being so disproportionate in Montreal, Vancouver, Lethbridge, Calgary, every city that it’s been measured, as if this is a new phenomenon, but it’s something that has a longstanding history, since policing really was instantiated in this country,” Maynard says.

“Policing was always racialized.”

PART II: Policing in the present

The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police on May 25 re-ignited a long-burning flame of protest against police violence in the United States and across the world.

In the months since his death, calls for the defunding and abolition of police departments across North America have become an overwhelming demand accompanying the Black Lives Matter movement.

Critics have pointed to inflated police budgets and seemingly unrestricted police powers against the backdrop of continued violence towards Black and Indigenous peoples.

According to the most recent Statistics Canada data, national police expenditures reached $15.1 billion in 2017-18, a two per cent increase from the previous year on a trend that has been notching upwards since 1996. At the same time, the nation recorded a two per cent drop in “police strength,” a term used to indicate the number of officers per 100,000 population.

The lion’s share of police operating expenditures goes into salaries, which average $99,298 annually across Canada.

“If people are sometimes confused about what it means to really insist that we could live in a world free of policing, it’s an understanding that policing has always been a kind of racialized control mechanism over Black communities, over Indigenous communities,” says Maynard.

“If we understand that history, it’s a very logical extension to say that this kind of violence actually needs to be reduced, needs to be eliminated entirely, and that’s what the call to defund, to abolish the police is getting at.”

In response to the beating of Chief Allan Adam in June, RCMP commissioner Brenda Lucki was called on to comment on systemic racism embedded in the ranks of the force. In an interview with the Globe and Mail, Lucki said she “struggled” with the definition of systemic racism and denied its existence within national police ranks.

She walked her comments back days later, penning a statement which acknowledged “systemic racism is part of every institution, the RCMP included,” and that the RCMP “have not always treated racialized and Indigenous people fairly.”

According to retired Vancouver police officer Lorimer Shenher, a denial of systemic issues and systemic racism is embedded deeply in policing, and particularly RCMP culture.

Attending police academy on the West Coast in the 1990s, Shenher says he was surprised at the lack of history taught to the bands of “freshly-scrubbed, well-meaning recruits.”

Instead, young officers were trained in the community policing principles of Sir Robert Peel — the father of British policing who touted the ideal that “the police are the public and the public are the police.”

With that training, Shenher says, officers across the country find themselves “baffled” by encounters with distrustful members of the public.

“They have no concept of why every person that they meet who has any knowledge of this history is then mistrustful, and doesn’t see them as a helper, doesn’t see them as somebody who’s going to make them safe, but quite the opposite,” he says.

“There’s just a fundamental lack of understanding of history and understanding of police’s role in that history.”

Winnipeg Police Service Chief Danny Smyth declined two separate requests for comment when the Free Press would not first disclose the identities of other sources for this story.

Often pitted against the United States, the culture of Canadian policing is one of exceptionalism, Shenher says. The revered vision of the Mountie takes root not only in broader Canadian narratives, but within the ranks, too.

“Police culture is they don’t like criticism because so many of them really see themselves as helpers,” Shenher says.

“The culture is so powerful in policing and the culture really survives through people denying their history and denying things like systemic racism — it’s that inability to look outside their own experience. They drink the Kool-Aid; they have to, I think it’s a survival mechanism, and it’s baked right into their whole DNA.”

Despite the pristine narrative, Canadian policing is marked by a dark score of racialized brutality and violence.

KEY FIGURES

1. Demographics

● According to 2018 Statistics Canada numbers, four per cent of police officers in Canada are Indigenous compared to five per cent of the population. Eight per cent identify as being a member of a visible minority compared to 22 per cent of the population.

● Winnipeg Police Service’s 2019 annual report indicates 11 per cent of officers identify as Indigenous and seven per cent identify as a member of a visible minority.

2. Calls for service

● Statistics Canada estimates that between 50 and 80 per cent of police calls are non-criminal in nature. They are referred to as ‘calls to service,’ and instead comprised of alarms, disturbances, overdoses, mental health calls, domestic disputes and traffic accidents.

● In Winnipeg, police were dispatched to 231,670 calls in 2019 and recorded a total of 69,294 criminal offences — 70 per cent of dispatches did not result in criminal offences. Of the Criminal Code offences in 2019, 74 per cent were related to property crime in Winnipeg. Of those, 14 per cent were resolved.

3. Cost of Policing

● According to 2018 Statistics Canada data, the average per capita cost of policing is $318 per person. Winnipeg spent $394 per person on policing in 2019.

● The Globe and Mail recently reported Canadian municipalities spent between eight and 30 per cent of their total budgets on policing in 2019. The biggest spenders were Longueuil, Que. with 29.8 per cent of the budget going to policing, followed by Surrey, B.C. at 29.4 per cent and Winnipeg with 26.8 percent.

In 2017, the CBC released Deadly Force, the first comprehensive analysis of police violence in the country. Between 2000 and 2017 there were 460 fatal interactions between police and civilians, averaging 27 deaths per year.

Most victims — nearly 70 per cent — were suffering from mental-health and substance-abuse issues at the time of their deaths.

Nearly 700 officers were involved in the fatal interactions, the largest proportion of which stemmed from the RCMP.

The vast majority of officers were never charged, an issue Shenher believes sits at the heart of policing’s ongoing culture of violence.

“What’s been lacking in policing right through history is not policy but accountability for those people that don’t follow the policy. Right up to the minister of public safety, there are very few mechanisms to hold police accountable for anything,” he says, adding more robust tools are needed to fire or discipline officers when necessary.

While the majority of victims were white, Indigenous and Black people were significantly overrepresented in the data. Indigenous people make up 16 per cent of deaths at the hands of police, but only four per cent of the population, annualized over the last 20 years. Similarly, Black people make up nearly nine per cent of deaths, but just shy of three per cent of the nation’s population over 20 years.

Nationally, both Indigenous and Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people and, in some jurisdictions, these numbers are starker.

Black people in Toronto — with the country’s largest population and police force — are 20 times more likely to be killed by police, according to a recent Ontario Human Rights Commission study. A similar 2017 report in Halifax found Black people were six times more likely to be stopped (note: not killed) by police than white people.

The Deadly Force data found that Indigenous people made up 10 per cent of Winnipeg’s population from 2000-2020, yet represented nearly two-thirds of deaths at the hands of police — 17 out of a total 28. In a 10-day span in April, Winnipeg police shot and killed three Indigenous people, including 16-year-old Eishia Hudson.

This year alone has been particularly violent for the country’s law enforcement agencies. CBC found that in the first six months of the year 30 people had died at the hands of police — the full-year average for fatal police encounters over the last decade.

PART III: Reimagining policing

Tensions between public and police erupted once again Sunday after police shot 29-year-old Wisconsin man Jacob Blake seven times in the back while he was getting into his car with his three children in the back seat. Protests erupted, including Tuesday night, when a two people were fatally shot and another wounded, as Americans — including professional athletes who temporarily shut down play in their leagues — once again rose to demand the end of racism and brutality in policing.

Maynard warns that Canada, however, cannot be complacent or turn a blind eye to violence on the homefront.

“It’s insulting to push the narrative that just because we don’t live in the United States that somehow Black people’s lives and deaths are somehow less valuable here, that somehow we should be less outraged because of anti-Black violence in another place,” says Maynard of the ideals of Canadian exceptionalism.

“It’s so representative of an acute crisis of racialized violence, of racial disparities, that it stands on its own, that it doesn’t need to be compared to the United States to be horrific. I think there’s really a refusal to look closely at the situation here, at the legacy of slavery, at the legacy of segregation.”

These violent historic practices have trickled into the shape and understanding of policing that exists to this day, sitting unacknowledged at the heart of current policing practices.

“The policing of Blackness is part of how this country was founded, it’s part of how this country has always operated,” says Maynard. “There’s been a long-standing hostility.”

She draws parallels between the policing of Black people in the early days of Confederation and the project of gentrification, pushing Black people out of affluent neighbourhoods, the war on drugs, crackdowns on immigration and other police practices that have resulted in disproportionately high arrest, incarceration and brutality rates for Black citizens.

Indigenous peoples, too, have been subject to violence and discrimination at the hands of law enforcement throughout the nation’s history and into the present day.

“Indigenous people are trying to protect their lands from what we all know will be an environmental disaster sooner or later, they’re trying to protect their lands and they’re being met with police oppression; they’re being arrested and jailed, they’re being threatened and harassed,” says Brownlie.

“The principle is the police are used as a paramilitary force to prevent First Nations from inhibiting the generation of wealth by white people.”

Depictions of violence and brutality, be they police killings, “starlight tours,” unjust arrests or disproportionate charges permeate marginalized peoples’ perceptions of policing throughout history.

The effect of these centuries of trauma, says Ennab, is a deep mistrust between marginalized communities and police.

“The distrust started with broken treaties, started with imposing a structural violence against their communities, and it’s natural from that perspective to be distrustful,” he says.

“Overall it was a relationship based on distrust and, in that sense, distrust is something that should be seen as positive, productive for conversations; it’s something that’s ethically needed. We need to be distrustful; we need to be mournful, we need to be angry, we need to confront injustice.”

Calls for defunding and abolition of police have been accompanied, in recent months, by more moderate calls for reformation — small, structural and policy changes such as officer-worn body cameras and independent investigation units that could punish “bad apples” in the system and create more accountability for officers.

Ennab, who has also provided anti-racist cultural competency training to police and other organizations, doesn’t believe systemic racism can be trained out of the institutions.

“Until the institutions are changed we’re going to continue to see racialized lives missing and murdered, and it’s more than just training or converting few bad apples,” he says.

“That’s where we need to go back to the history, look at the dispossession and talk about the history openly, not with myths, to be able to listen to Indigenous communities when they’re mourning, instead of stigmatizing them.”

Shenher agrees, noting that the existing structures for accountability haven’t worked for many years, and independent police investigators units, such as Manitoba’s Independent Investigation Unit or Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit, are often staffed by former officers still entrenched in old policing mindsets.

Those calling for defunding and abolition have maintained that the structures of policing are not broken, but instead are working exactly as historically intended, and that in order to achieve justice the systems of public safety need a fundamental restructuring.

“Moving into the kind of safety that Black people would need, that Indigenous people would need actually relies on us to think about public safety differently,” Maynard says. “Without police.”

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @jsrutgers

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a climate reporter with a focus on environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a three-year partnership between the Winnipeg Free Press and The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, August 31, 2020 4:54 PM CDT: Corrects date of the RCMP's March West