Horror of Hiroshima must push us to peace

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/08/2020 (1954 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There are many numbers to tell the story of what happened in Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. There are the grim tallies of suffering: an unbearable count of the dead, and a nearly uncountable reckoning of destruction. Around this, there is one humble number that quietly tells a haunting tale of the truth of the nuclear bombing.

That number is five. Just five. Five photographs known to have been taken in the city that day.

These five images were taken by one man, Yoshito Matsuhige, a 32-year-old newspaper photographer who lived a few kilometers from the hypocentre. Injured by flying glass when the blast ripped through his house, he grabbed his camera and set out towards the inferno that raged over Hiroshima’s downtown.

At a bridge near his home, Matsuhige encountered a group of survivors, mostly children. They staggered together, clothes and skin both dangling from their bodies like rags, while police officers poured cooking oil on their burns. It was the only relief many would find in the desperate hours after the bombing.

Matsuhige lifted his camera, but was so disturbed by what he saw that he struggled to push the shutter. He finally forced himself to take two photos on the bridge, before moving on: “Even today, I clearly remember how the viewfinder was clouded over with my tears,” the photographer recalled in an interview many years later.

Closer to ground zero, he stepped into a charred streetcar and found a jumble of 15 corpses, stripped naked by the blast. This time, he touched his camera, but couldn’t bear to take a picture; for the next three hours, Matsuhige explored Hiroshima’s scorched and desecrated heart, but he did not take another photo of its horrors.

He was not alone. Of all the army or newspaper photographers in the city that day, none appears to have taken any images in those first 24 hours. Matsuhige’s five photos stand as the only visual testimony to one of the most history-changing moments of the 20th century, and even they were chosen to avoid the brutality of what he saw.

So it is that the near-absence of photos tells its own story of the monstrous inhumanity that marked the violent dawn of the Atomic Age. Its horrific sights were seared into victims’ eyeballs and brains, to forever haunt the memories of those who could not look away, including the photographers who put down their cameras.

In that moment, Matsuhige and others made a declaration of humanity, at the very time and place that it had been most degraded. What images persist of the hours after the bombings, they come from the testimony and drawings given by survivors, who often find in their recollections a compassion denied to the bomb’s victims.

This week, as the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki approach, I thought of this again. I thought about it as videos emerged from Tuesday’s devastating explosion in Beirut, videos in some cases livestreamed by people who reportedly died in the blast. We can all be made eyewitnesses now, in an instant.

And this is important, because how we understand history is so often made in a battle over public perception, and images can be weapons in the service of peace. Think of the image of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, a little girl fleeing a U.S. napalm attack on her Vietnamese village; think of the photo of Alan Kurdi, drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

Indeed, it took years for the whole truth of what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to become known. In 1947, as detailed reporting began to come out, the American public began to grow uncomfortable with what it was learning. In response, U.S. war secretary Henry Stimson penned a piece for Harper’s magazine, defending the bombings.

Stimson’s argument — that the bombings were required to end the war sooner, with fewer casualties — was quickly adopted by a majority of Americans and those in allied countries, who, quite frankly, didn’t want to think too deeply about the moral culpability of the atomic bomb, about the indiscriminate horror unleashed on civilians.

That explanation shaped generations of public opinion. Even today, most believe the bombs were justified.

In fact, the sum total of historical evidence tells a far more complicated story. There’s not enough space here to litigate that fully, except to say that the bombs were as much an opening salvo in the Cold War as a finale to the Second World War; how much they actually hastened the end of battle is in doubt, as are Stimson’s casualty estimates.

Everyone should study this evidence, and come to their own convictions. Mine are, to put it simply, that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are among the most heinous war crimes ever committed, crimes for which no one responsible would ever pay a price. The only justice will be to ensure their horrors are never forgotten.

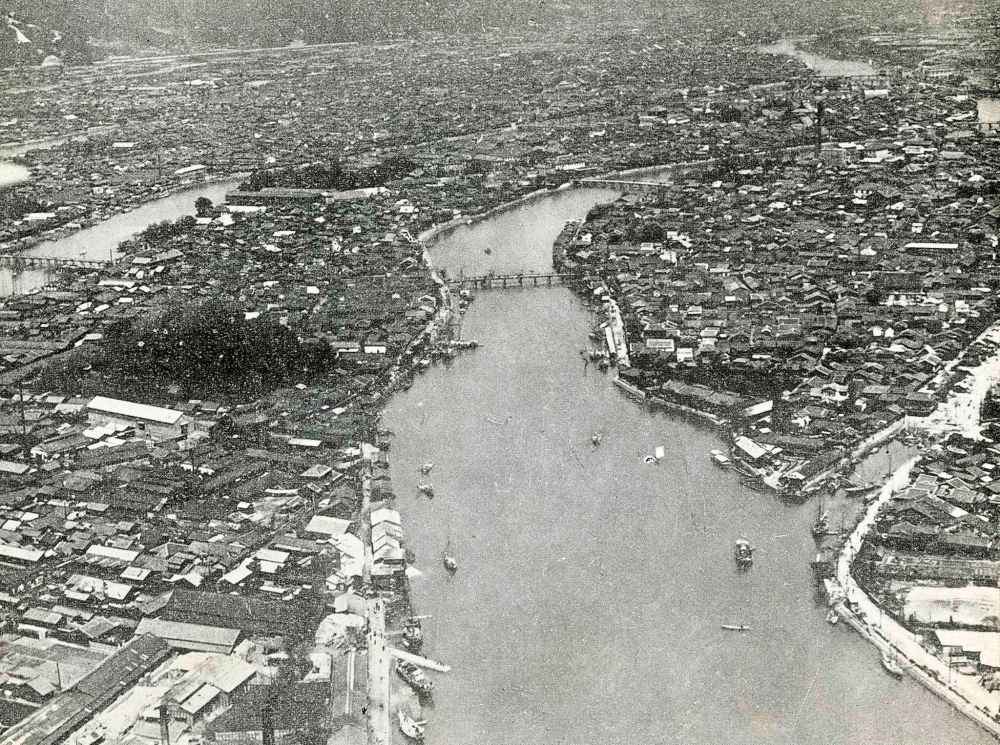

That isn’t to say that life does not go on. Today, neither city is defined by the bomb: they are beautiful and vibrant, each nestled between mountains and the glittering blue sea. In the spring, cherry blossoms scatter over the rivers around Hiroshima’s Peace Park, and people gather under the trees to sip sake and laugh into the dusk.

Everything can heal. Every hell can become a paradise, given enough time and peace to let life unfold.

So when the rest of the world thinks of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they think first of a horror that can be imagined more than seen. But in Japan the most common word associations, at least according to Google searches recently run by historian Nick Kapur, are for Hiroshima-style cabbage pancake and Nagasaki’s famous castella sponge cake.

And today, one of the photos Matsuhige took at that bridge holds a stark, gut-wrenching vigil near the entrance to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The museum was renovated last year, one of many sites across Japan to get a facelift in preparation for what were supposed to be the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Thursday, on the 75th anniversary of the bombing, the world was supposed to be converging on the country to share in the promise of peace. Hiroshima itself was planning a major ceremony, to be attended by prominent world leaders, calling for nuclear disarmament and to remember the horrors of nuclear war.

Instead, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the Olympics have been postponed until next year. The ceremony to mark the Hiroshima bombing, which began at 4:30 p.m. Winnipeg time Wednesday, was stripped down, with speakers participating by video. A vigil scattered by circumstances, calling on all of us instead to remember where we already are.

That will be the way of things soon. The average age of survivors is now 83; in a handful of years, the truth of the bombs will pass out of living memory. It will remain held for posterity by hundreds of drawings, hours of eyewitness testimony, thousands of artifacts and documents… and just five photographs of that day.

These come from many sources. But taken together, they speak with one voice, one soul and one message: let there be no more Hiroshimas. Let there be no more Nagasakis. Let us never again unleash the most destructive forces of the world on each other, and let us never forget the memory of sights too horrible to be seen.

“We hope that such suffering will never be experienced again by our children and our grandchildren,” Matsuhige said in his testimony. “All future generations should not have to go through this tragedy. That is why I want young people to listen to our testimonies and to choose the right path, the path which leads to peace.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.