Provinces vary in disclosing pandemic data

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/04/2020 (2080 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The number of people infected with the novel coronavirus has crept above one million globally, and questions are being raised about the scattershot, patchwork approach Canadian provinces are taking when disclosing pandemic data to the public.

Health authorities across Canada are being asked to balance competing interests, including privacy rights and public safety concerns, when deciding what to reveal — and in what detail — as the pandemic continues to spread.

The result is a vast discrepancy in the public health information available to Canadians based on where they live.

A Free Press analysis of COVID-19 data disclosure shows Manitoba is in the middle of the pack when it comes to the level of transparency provinces employ as the virus spreads.

When the pandemic took root in Manitoba, chief public health officer Dr. Brent Roussin, who has been holding daily news conferences for weeks, revealed not just aggregate data on the outbreak, but also case-specific detail.

With each new case, Manitobans were provided the following information: approximate age, gender, general geographic location, and travel history.

By late March, that had changed. Now, Manitoba only releases aggregate data as the number of infections continues to rise.

On Thursday, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said he plans to work with provincial governments to improve the sharing of data in the country. He also said modelling projections for how the pandemic may spread should be made public in the future, as has been done in other countries.

So far, provinces have not had a uniform approach to what the public should be told.

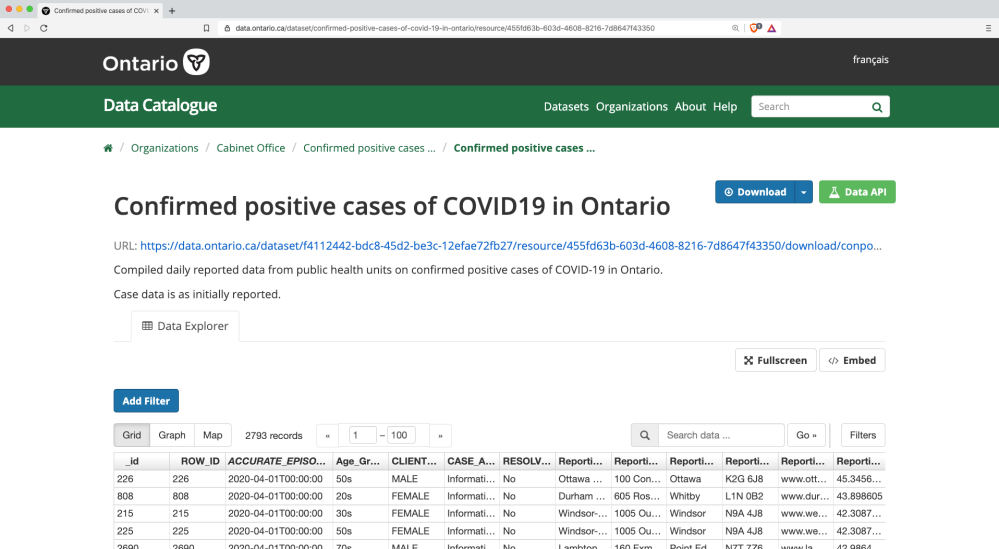

Two provinces leading the way on the breadth of information released to the public, British Columbia and Ontario, happen to be two of the hardest hit. In B.C., there are at least 1,066 COVID-19 cases, with 25 deaths. Meanwhile, Ontario has had 2,793 cases, including 53 deaths.

On many fronts, B.C. has been the most transparent of all provinces. Last week, government officials revealed not just the statistical models they’re using, but also provided a detailed accounting of medical resources, from ventilators to hospital beds.

Both B.C. and Ontario provide the public with aggregate data and epidemiological summaries. Ontario recently began uploading case-level information into the province’s open data portal.

In a written statement to the Free Press, a Manitoba government spokeswoman said multiple factors went into the decision to claw back the depth of information provided to the public on COVID-19 infections.

“From a public health reporting perspective, individual case data is less helpful than collating data over time. Age and gender are much more meaningful when collated, because it helps identify any trends in testing or cases over the long term,” the spokeswoman said.

“Providing collated data (also) helps reduce the risk of someone being identified by their personal health information.”

In addition, the spokeswoman noted the province has finite resources, so focusing on aggregate data “reduces the strain on front-line public health staff as they work to investigate cases and respond to the pandemic.”

But it remains unclear how minimal details such as age group, gender and general geographic location breach privacy concerns. Releasing raw numbers without such detail could also have a dehumanizing effect, while keeping the public in the dark about who is getting sick and where.

Crisis communications specialist Donald Steel said public health authorities across the globe, including provincial governments in Canada, are dealing with an incredibly difficult situation.

Speaking generally, Steel said it’s possible provincial governments don’t have the resources needed to compile the type of data many Canadians would like to see.

He also said governments must perform a delicate balancing act: weighing privacy concerns versus the public’s right to information, and respect for civil liberties versus mandated social distancing measures.

“There’s a general principle in communications where you want to give enough information so the public recognizes the seriousness of what’s going on, but not so much it isn’t helpful or can cause people to be overly fearful. We want the public to be alert, but not alarmed,” Steel said.

“Having said that, consistency across areas in terms of how the public is being informed would be a good thing.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

michael.pereira@freepress.mb.ca

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.