Public has power in fight against COVID-19 Individual behaviours 'the most important variable,' in how Canada fares against virus, says head of public health association

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/03/2020 (2105 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Health officials in Manitoba and across Canada are applying the lessons learned during the H1N1 and SARS outbreaks to respond to COVID-19.

The question they have is whether Canadians will do so too, as doctors urge the public to stay healthy and avoid crowds.

“There could be a degree of pressure and demand on our health system that exceeds our capacity,” said Joel Kettner, who oversaw Manitoba’s response to both large outbreaks as the province’s public health chief from 1999 to 2012.

That term included the 2003 SARS outbreak, which led Canada to reboot its public health system.

The disease from China took root in Toronto, killing 13 people in Canada.

A year later, a national advisory committee issued a large report calling for more prevention, streamlined lab resources and a stronger role for health authorities.

The report led Ottawa to split Health Canada and create the Public Health Agency of Canada, to put a focus on preventing disease and managing its containment.

The report also helped create protocols to assess and categorize possible epidemics. For example, SARS infected many health-care workers before officials realized it was an airborne disease. That’s unlike COVID-19, which spreads through contact with humans and surfaces.

The World Health Organization (WHO) improved its data collection from various countries. Sharing genome sequences and diagnostic instructions now has scientists worldwide helping each other to deploy testing much quicker.

Meanwhile, provinces created chief officers that operate at arm’s length from the elected governments that appoint them.

That’s allowed jurisdictions to respond based on local needs, like whether to close schools, while still co-ordinating national responses and reporting the data centrally.

Ian Culbert, head of the Canadian Public Health Association, contrasts that with the United States.

The Trump administration has had the White House take over communication from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and local mayors have often been tasked with informing the public.

Canadian authorities instead have a protocol that outlines jurisdictions and reporting duties, Culbert notes.

“We did pandemic planning, and those plans weren’t gathering dust on a shelf; they were kept up to date and now we’re implementing them.”

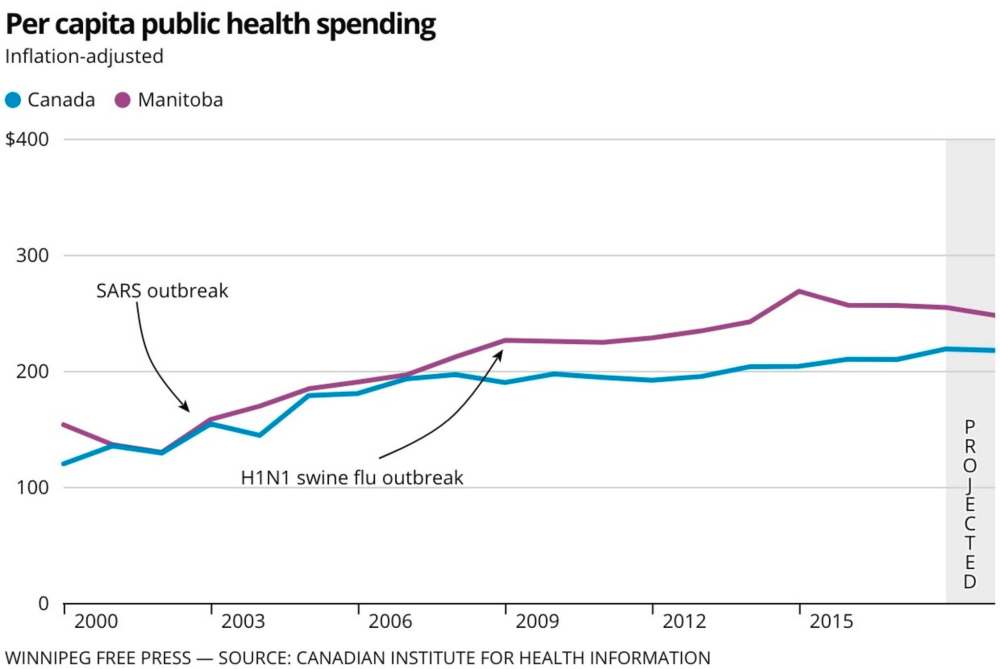

Governments have also ramped up their spending in the past two decades on prevention, research and public awareness, though it’s hard to tell whether it’s adequate.

Data compiled by the Canadian Institute for Health Information shows that provinces spent $11 per Canadian on public health in 1975 (or $56 in today’s numbers, when adjusted for inflation). In 2000, governments spent $114 per person, and a projected $296 this year.

Manitoba falls in line with those numbers, and Kettner said provincial governments seemed to boost funding after outbreaks in the past. Generally, his budget was left stable after each of these increases.

However, Manitoba’s data meshes public-health lab testing and nurses with active-living programs. CIHI says many provinces lump together occupational health campaigns and drug addictions services with conventional public-health nurse budgets.

Officially, public health makes up 6.5 per cent of general health spending in Canada under CIHI’s definition.

But University of Saskatchewan epidemiology professor Cory Neudorf suggests governments have cut back. He’s been part of studies that have examined provincial spending, and found some provinces could be inflating their numbers by double, given how much they classify under public health.

“Public health, in most provinces, operates on a very tight budget. So there is no surge capacity or very little in times of crisis — like now,” Neudorf said.

He noted that contact-tracing after someone is infected is a specialized skill that is crucial to containing a disease’s spread. In many parts of Canada, public-health staff will likely soon be taken away from vaccinations and other key duties for such tasks.

“We did pandemic planning, and those plans weren’t gathering dust on a shelf; they were kept up to date and now we’re implementing them.”

– Ian Culbert, head of the Canadian Public Health Association

That’s because there are few trained staff who normally work full-time on secondary tasks like public awareness, rehabilitation classes and assessing health systems.

“The tyranny of the urgent usually wins out, in times of austerity,” Neudorf said.

It’s unclear how bad COVID-19 will hit Canada.

Federal Health Minister Patty Hajdu said her officials estimated 30 to 70 per cent of Canadians could become infected. The WHO has estimated COVID-19’s death rate at 3.4 per cent.

Kettner, who is now a University of Manitoba professor in community health, noted that the H1N1 swine flu stabilized quickly, allowing authorities to figure out who was most likely to get infected — young people and those living in disadvantaged Indigenous communities — and target people with a vaccine that was created relatively quickly. They generally knew how many cases to expect.

With COVID-19, officials are trying to contain the spread, because many people can transmit to more vulnerable people without actually feeling sick themselves.

Cities like Ottawa have already moved diagnostic testing outside the hospital, allowing a swab test in the patient’s driver seat, to avoid cross-contamination. Manitoba officials are exploring the same idea.

“It has huge implications,” Kettner said. “I didn’t have to make those tough decisions in H1N1. It looks like that might have been a cakewalk, compared to what’s happening now.”

Kettner noted that the WHO called out “alarming levels of inaction,” by governments when it declared COVID-19 a pandemic, which is not the typical language used by United Nations officials.

In Italy, where containment measures were enacted late, doctors have been warned they may have to ration ventilators and other equipment, which could include turning away the elderly.

During H1N1, the province only had about 100 ventilators, according to a 2010 review. As of Friday, Manitoba has 243 ventilators, with 20 more on order, according to Lanette Siragusa, chief nursing officer for Shared Health. Both numbers exclude operating rooms.

Kettner expects Manitoba hospitals could see patients in hallways, or surgeries rescheduled — but he doesn’t expect ventilators to be maxed out.

“I don’t feel very worried the system is going to be overwhelmed to the point people are going to be dying in the streets, who can’t get into the hospital,” he said.

“We’re tested every year with influenza, and there’s always a really bad week or two that stresses the system to the max.”

Kettner says Manitoba in particular is vulnerable to Canadian outbreaks, because of its sheer number of remote communities, as well as how many Indigenous people live in poverty and cramped conditions where disease thrives.

He said it’s hard to build immune resistance without adequate food and sleep. Limiting stress, avoiding smoking and doing exercise helps to fight off illness as well.

That’s why Kettner worries about the knock-on effect of isolation, with large events being cancelled.

“The unemployment, the cost, stress and anxiety — maybe that is going to put someone at more risk for getting sick than working; I don’t know,” said Kettner.

“As a public-health doctor, you have to think broadly.”

Regardless, he stressed that coughing into an elbow and frequently washing one’s hands are among the most effective measures to stop the spread.

Culbert says the public has more control than health professionals over how Canada fares with COVID-19.

That’s why so many of his colleagues are urging people to avoid crowds, check up on their neighbours and have bosses allow employees to work from home.

“If we can do measured responses that are in keeping with the severity of the outbreak early on, it’s going to mean that we’re not going to have to do more severe or draconian measures later on,” Culbert said.

“Our individual behaviours will be the most important variable in how well Canada responds to this outbreak.”

— with files from Carol Sanders

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Friday, March 13, 2020 10:23 PM CDT: Fixes typo.