From footnote to martyr: execution altered Scott’s place in history

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/02/2020 (2217 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

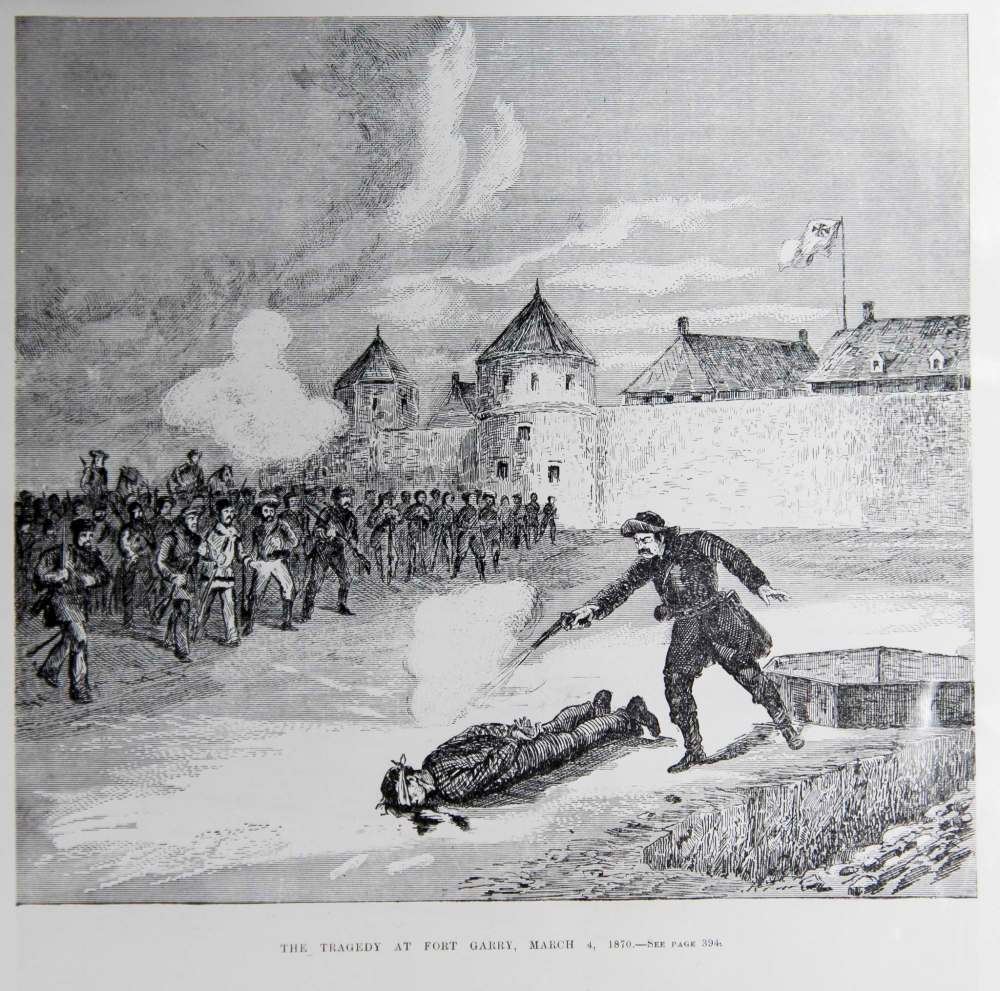

When Thomas Scott was marched outside the walls of Upper Fort Garry and executed by firing squad, it forever changed how history would treat Louis Riel and the Red River Resistance. The killing of Scott, whether a misguided error by Riel or an unavoidable step to prevent further bloodshed, would turn out to be one of the most pivotal events of the resistance.

Only a month after the Irish-born Canadian was condemned to death in March 1870, Riel opponents in Ontario used Scott’s execution to whip up anti-Métis sentiment in an effort to sabotage negotiations between Ottawa and the Red River Settlement. It nearly worked. Two of three Red River delegates sent to Ottawa to negotiate the terms of Manitoba’s entry into confederation were arrested on arrival (but later released) for Scott’s death. At the same time, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald was under increasing political pressure to send military troops to quell the resistance in Red River, rather than engage in peaceful negotiations.

Scott’s death didn’t just complicate matters for the Red River delegates. It undermined their efforts to bargain with Ottawa.

Scott was tried and convicted by a “military council” on March 3 for rebelling against the provisional government and attacking a Métis guard at Upper Fort Garry, where he and other political prisoners were held. The trial wasn’t conducted under normal court rules, even by 1870 Red River standards. Scott had no defence counsel and wasn’t present for much of the proceedings, which were conducted in French (a language he didn’t understand). Riel, one of the chief witnesses in the case, had to act as translator. The military council was not unanimous in its decision to sentence Scott to death. Some felt the penalty was too harsh.

After failed pleas by several prominent members of the community to spare Scott’s life, he was taken outside the east walls of Upper Fort Garry on March 4 — roughly where Fort Garry Place’s parking lot is today — and shot by firing squad. According to some witnesses present — about 100 bystanders arrived after hearing word of the planned execution — Scott didn’t die right away. One of his executioners shot him again at close range with a revolver.

Scott was then placed in a makeshift wooden coffin and brought back inside the fort. Endless rumour and speculation swirled around how the execution was carried out, including whether the executioners had been consuming alcohol at the time. His time of death, including the possibility that he remained alive for several hours after the execution, has never been settled. Even the whereabouts of his body remains a mystery. Some reports had him buried on the grounds of Upper Fort Garry. Others said several Métis cut a hole in the ice of the frozen Seine River and secretly dumped his body there. His remains were never recovered.

No other single event that occurred during the Red River Resistance has attracted more debate and commentary from scholars and historians. Many saw Scott’s execution as a grave error that could have been avoided. The killing has been described as illegal and morally reprehensible. Others saw it as a necessary step to maintain order in the settlement and to show Ottawa the provisional government meant business. Prior to Scott’s execution, several prisoners had been tried and condemned to death but were spared by Riel.

If Scott, who was relentlessly abusive towards Métis guards while in captivity, had not been executed through some form of tribunal, he may have been murdered by guards without any due process at all, others have speculated.

“Almost every historian over the years has condemned the execution of Thomas Scott as being without any legal foundation,” wrote Maggie Siggins in her biography <Iz>Riel: A Life of Revolution.<z> “But the Métis and Riel believed the government was a legitimate one, invested with the power to mete out justice and impose the death penalty if need be.”

Whatever the case, Scott’s death not only made it more difficult for the provisional government’s delegates to negotiate with the federal government, it changed Riel’s life forever. The Métis leader fled Red River later that year when the Wolseley military expedition arrived from Ontario. He became a fugitive for life, unable to take his seat in Parliament after he was elected several times as an MP, fearing arrest or other forms of reprisal.

Ambroise Lépine, one of the top officials in Riel’s provisional government who presided over the Scott trial, was the only one ever convicted for Scott’s death, four years after the resistance.

Alive, Thomas Scott would barely warrant a footnote in the story of the Red River resistance. Dead, he became a martyr for an anti-Métis cause in eastern Canada that changed the course of Manitoba history.

— Tom Brodbeck

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

![Thomas Scott (c. 1842 – 1870) was an Irish-born Canadian and fervent Orangeman. Scott was born in the Clandeboye area of County Down, in what is now Northern Ireland.[1] He was recruited by Canada to fight in the Red River Rebellion and was captured and imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry by Louis Riel and his men while trying to attack it along with 34 other volunteers. Scott made an attempt to escape but was recaptured by Riel's men and was summarily executed for committing insubordination. Scott's execution led to an outrage in Ontario, and was largely responsible for prompting the Wolseley Expedition, which forced Louis Riel, now branded a murderer, to flee the settlement. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Scott_%28Orangeman%29](https://dev.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/Thomas+Scott.jpg?w=100)