The decade that rushed by Amid curated social media, binge-worthy TV, we had Greta, Beyoncé, Keanu and Baby Yoda

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/12/2019 (1828 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Ah, the 2010s. The decade that didn’t really have a name — the 2010s? the teens? what are we calling it? — was also the decade in which everything felt both slower and faster, thanks to non-chronological social media algorithms, entire seasons of TV arriving at once, and push notifications making everything from news alerts to texts seem like pressing emergencies.

Whatever it was, it’s over. And a lot happened, especially in popular culture.

Keanu Reeves had a Keanussaince. Matthew McConaughey had a McConaissance. We communicated by emoji; we reacted in GIF. A hockey mascot named Gritty became an unlikely folk hero. A Pakistani teenager named Malala Yousafzai and, later, a Swedish teenager named Greta Thunberg, became avatars for hope.

Here, in no particular order, are 10 pop culture moments that shaped the decade.

The rise of binge-watching and Peak TV

This was the decade when Netflix morphed from a subscription DVD company into a streaming giant that helped to radically change how we watch TV.

In 2013, Netflix launched the political thriller House of Cards, its first original series — and made all 13 episodes of its first season available immediately. We no longer had to wait week to week for new episodes; we could consume entire seasons of TV in the space of a single weekend.

Other big streaming players, including Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, and Crave in Canada, began releasing original programming under this model, while premium networks such as HBO and Showtime, kept vying for eyeballs with prestige programming.

The result? The era of Peak TV. By 2018, there were nearly 500 English-language scripted original series available for viewing; of those, 160 were produced for streaming services.

The podcast boom

Podcasts pre-date the 2010s (it’s a portmanteau of iPod and broadcast), but this decade saw a bonafide podcast boom.

The appeal isn’t hard to understand: like blogs before them, pods are accessible and approachable; there’s an intimacy and looseness to them that traditional forms of media don’t have.

From comedy/interview hybrids such as WTF with Marc Maron to true crime pods such as Serial to non-fiction series such as Dolly Parton’s America, podcasts cover a huge range of topics and have become just as anticipated and talked-about as TV shows and movies.

They also became big business this decade; that’s why you hear everyone selling the same meal-delivery kit or mattress in a box on their podcast.

The funhouse mirror of Instagram

When Instagram debuted in 2010, it was a way to share heavily filtered photos of latte art, sunsets, selfies and avocado toast.

Then, people started “curating” their grids, presenting carefully constructed highlight reels of their lives for the dopamine hit that “likes” provided.

People began to leverage those likes into fame and money via lucrative brand deals, giving rise to a whole industry of “influencers.”

Studies have shown Instagram makes us feel bad about ourselves, and yet we can’t stop scrolling. By 2019, Instagram had over one billion active users.

The reign of Beyoncé

If the decade belonged to anyone, it was Queen Bey.

In 2010, Beyoncé released 4 — the album that gave us Run the World (Girls) and Love On Top — but her ascent to the upper echelons of pop music ramped up with the release of a pair of masterworks: her surprise self-titled album in 2013 and Lemonade in 2017. Both albums established her as a capital-A Artist, willing to take major creative risks.

But Beyoncé’s music was only part of her cultural dominance in the past decade; in everything from her 2018 Coachella headlining performance — henceforth known as Beychella — and accompanying documentary, to her now-famous Instagram photo announcing she was expecting twins, the control she’s had over her own image has given her an air of untouchability, aided by her adoring and highly protective superfans, a.k.a. the Beyhive.

The #MeToo movement

A movement that was founded on nascent social media a decade prior by activist Tarana Burke was given new life after the explosive sexual abuse allegations levelled against former film producer Harvey Weinstein in October 2017.

Our culture had put powerful, abusive men upon pillars for too long, and the #MeToo movement pushed them over, leading to real shifts in workplaces in every sphere — particularly the entertainment industry.

Predators were no longer protected, fans began to take a long look at who they were supporting and why, and the industry began to take real steps to stamp out abuse, including with the wider use of intimacy co-ordinators and directors on film and stage sets.

The Drag Race effect

RuPaul’s Drag Race, RuPaul Charles’ glitzy reality competition series dedicated to finding “America’s next drag superstar,” debuted in 2009 and, in the intervening decade, has normalized a marginalized art form by putting it firmly in the mainstream.

Drag had been around for decades but, for a long time, it was largely confined to cabarets, LGBTTQ+ bars and Pride parades. Now, it’s not uncommon to see Drag Queen story time in public libraries.

Many queens, including Drag Race alumni, sell out theatre shows. People are sharing the art form through reaction GIFs and memes. Teenagers are fully fluent in drag slang.

Drag Race is entertaining, to be sure, but it’s also served as an important entrypoint into larger conversations about gender and sexuality.

The comeback of astrology

“Mercury is in retrograde” was the unofficial slogan of the latter half of the 2010s, when astrology entered a new age.

Millennials, in particular, were flocking to astrology apps and calling their parents to get their exact time of birth so they could divine identity and meaning from the stars.

Astrology was no longer relegated to the backs of women’s magazines; one’s sun, moon, and ascending signs became a key part of one’s personality — or, at least, a key part of understanding memes and jokes online.

Whether you think it’s pseudo-science or regard it a spiritual practice, astrology can offer a little comforting clarity in uncertain times.

The endless reboots and remakes

This decade brought us a near-constant stream of blasts from the past, whether it was the resurrection of 1980s and ‘90s sitcoms such as Roseanne and Will & Grace or the string of live-action remakes of Disney classics such as Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King and Dumbo or the streaming sequels we didn’t know we needed (Fuller House, Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life).

Nostalgia for the ‘90s was a dominant fashion trend in the 2010s as people who grew up in that decade became adults; it stands to reason that movie studios and television networks would capitalize on that.

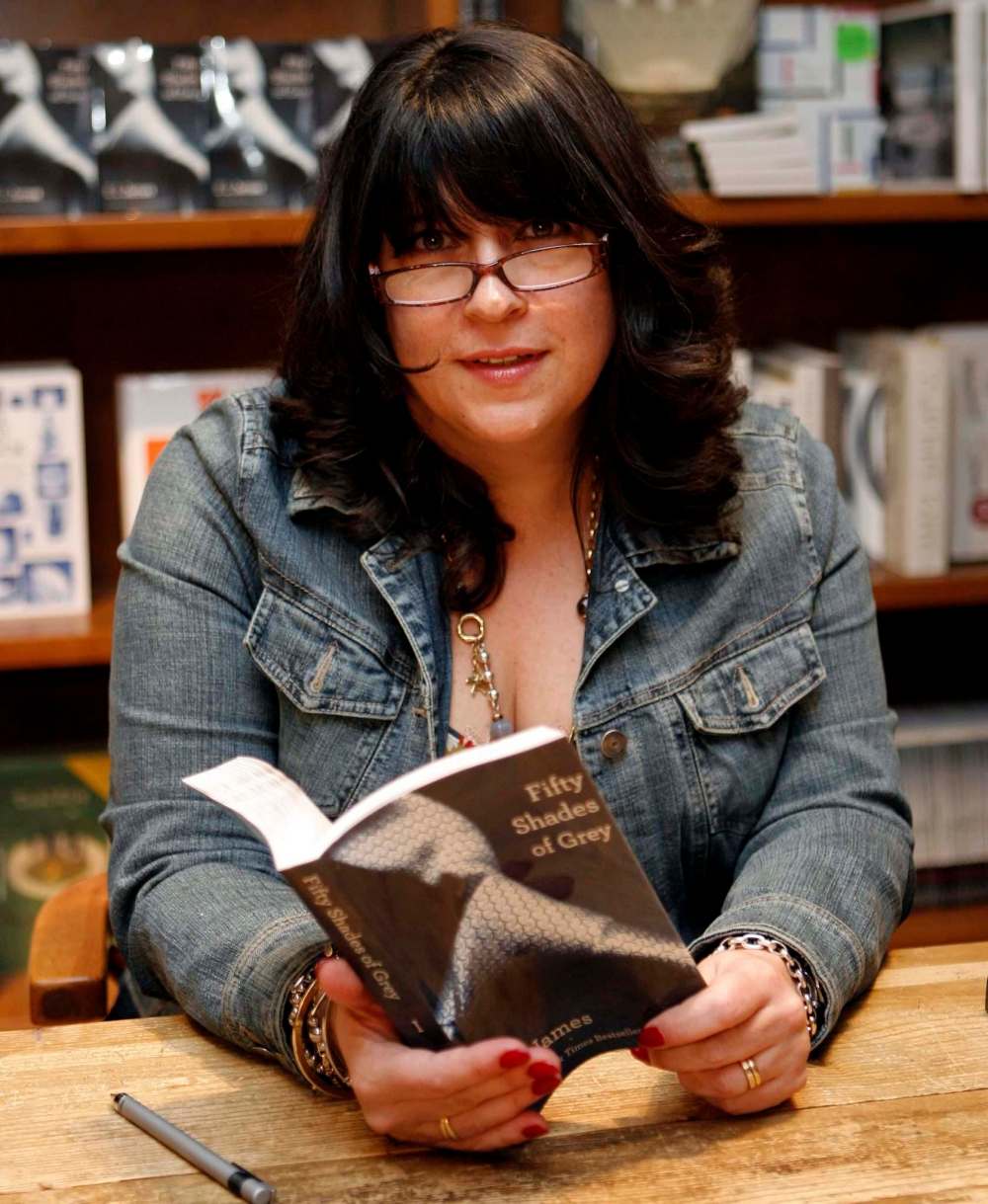

The questionable kink of Fifty Shades of Grey

Yes, that happened this decade! The first novel in E.L. James’ horny trilogy, Fifty Shades of Grey, was published in 2011, followed by two more novels and an astonishingly bad film series starring Dakota Johnson and Jamie Dornan.

The book, which was originally self-published, was mocked for its poor quality, dismissed as “housewife porn” — which is deeply condescending — and criticized for its portrayal of BDSM, and yet ended up being the best-selling book of the decade in the United States.

Well, at least people are reading.

The birth and memeification of Baby Yoda

In the dying days of the decade, a little green toddler with pointy ears united the internet — nay, the planet.

Baby Yoda quickly proved to be the breakout star of The Mandalorian, Jon Favreau’s excellent Disney Plus series set in the Star Wars universe. Memes quickly proliferated. People started getting Baby Yoda tattoos.

To be sure, Baby Yoda is unbelievably, objectively cute; you will want to protect him like he is your own baby, and you’ll miss him when he’s not on screen.

But the meme-ification of Baby Yoda is also a micocosm of memes — those easily shareable, digestible bits of content — more broadly. In the 2010s, memes became fundamental to how we communicate with one another online.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti

Columnist

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, December 31, 2019 9:08 AM CST: Removes duplicated sentence