Good days for our game Current, former elite-level hockey players willing to expose abuse, putting coaches, enabling managers on notice: there's no place left to hide

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/12/2019 (2197 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The song of Canada unfurls when the snow glints bright and the air is bracing but not bitter. It echoes in all sorts of places, from Toronto to sleepy Prairie towns and northern First Nations. An icy scrape, a rubbery smack, ripples of laughter and young exhilaration. It is vivid music, winter music, and it could never really hurt you.

Or there are the other sounds, the ones few people felt safe to talk about until now, when those who lived it finally smashed through the walls that long muffled their screaming. The sound of cruel words, flung to hurt. The sound of bodies striking bodies, not in the course of physical competition but in the abuse of power.

This is what the NHL is wrestling with now, and not just the NHL, but all the leagues that churn out its players, and some outside it, too. Abusive coaches. Sexually and physically abusive hazing gone unpunished. Players who, their careers long over, still feel the sting of things said and done to them, or things they were made to do.

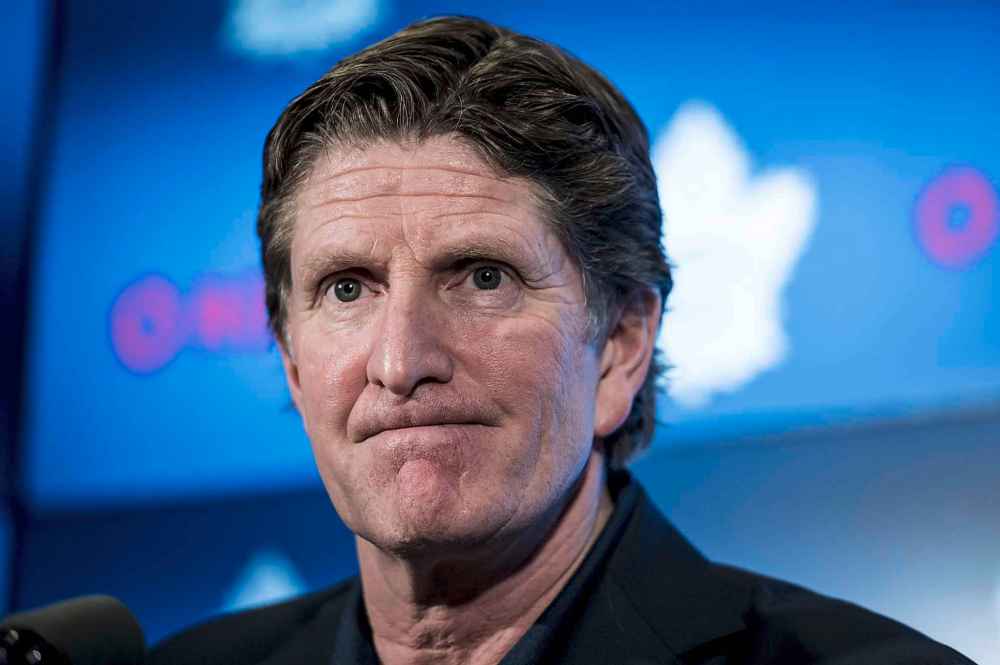

They call it hockey’s great reckoning, its turning point, its #MeToo moment. They can call it whatever. When the Toronto Maple Leafs fired Mike Babcock late last month, it was as if a dam broke loose, flooding the sport with reports of psychological abuse inflicted on players by him and others. That was only the beginning.

It was hard not to feel that something was shifting. Within days, Calgary Flames coach Bill Peters “resigned” amidst allegations he used racial slurs when reprimanding Akim Aliu, a black player. The Blackhawks suspended assistant coach Marc Crawford, now the subject of multiple allegations of physical and mental abuse.

And the stories kept rolling on, with whispers of more to come, and suddenly, it seemed as if the NHL was listening. Days after Peters was fired, Aliu met with top NHL brass, and came out of it sounding surprisingly enthused: there’s “big change coming,” he told reporters, adding that he was excited to see it move forward.

In this milieu, voices familiar, or not so much, were suddenly given platforms to flourish and to tell their truths.

The most powerful of these comes now from retired winger Daniel Carcillo, who first spoke out last year about the brutal hazing he endured as an OHL junior. Now, he rises to the fore not only because of his willingness to confront hockey’s most powerful dealers, but because of the connections he draws between abuse taken and given.

While Carcillo played, he was easy to dislike: he played dirty. He said cruel things on and off the ice. He admits to these now, openly, but gently points critics back to the core problem; once, he was just a kid with a dream, plucked for his talent and thrown into the funnel that grinds youth into grist for the pro hockey machine.

Someone built him into the player he became. Someone trained him that way. Kids whiffing at pucks in backyard rinks don’t grow up with dreams of hurting people. They’re just lost in the music of the game. It’s what happens to them along the way that shifts their thinking.

“My past is proof of purchase,” Carcillo wrote on Twitter, as powerful a statement in so few words as can be remembered.

As days move forward & the truth continues to surface about people & abuse in the hockey world, more & more ppl would like to try & discredit the stories of abuse bc of my past

My past is proof of purchase

I am guilty of being a racist, homophobic bully on & off the ice

— Daniel Carcillo (@CarBombBoom13) December 3, 2019

In an earlier tweet, he’d expanded on this thought. “The way I played and how I treated (people) off the ice was a direct reflection of the hockey environment I grew up in,” he wrote. “I was bullied and became a bully. I was abused and am guilty of abuse.”

2/ As for the media members who are trying to attack my character & on ice playing style

The way I played & how I treated ppl off the ice was a direct reflection of the hockey environment I grew up in

I was bullied & became a bully

I was abused & am guilty of abuse

— Daniel Carcillo (@CarBombBoom13) November 29, 2019

What came to define the moment, like so many others that have surged through the world, is that, in this clear-eyed honesty, Carcillo gave others permission. In replies to his tweets, others began to come forward, both to give their testimony as victims of abuse in sport at all levels, and also to admit acting as its perpetrators.

This moment is the key to all great social transformations; sunlight is a disinfectant, and before those who harm can be held to account, there must first be a full accounting of the harm. To support the calls for this accounting is not to attack the sport — it is, in fact, an act of love for all of those who played it, and all those yet to come.

Because hockey is not the problem, just like gymnastics was not the problem, just like movies weren’t the problem, or faith in God. The problem wherever abuse finds space to fester is never the particular of the place; it is always about the balance and imbalance of power, the systems built to stifle dissent and elevate some above others.

And so any institution where some are powerful and some are not risks giving cover to abusers; this is the source of the rot. On social media, many dug in their heels, chiding that the whole debate was over a “few bad apples,” and that engaging in it at all amounted to a smear job of the majority of decent, caring coaches.The problem wherever abuse finds space to fester is never the particular of the place; it is always about the balance and imbalance of power, the systems built to stifle dissent and elevate some above others.

But the problem has never been that most coaches are bad; they aren’t, which everyone who has been in or around the game knows deeply in their heart. The problem now being exposed is the systems that give room for the abusive coaches to rise through the ranks, unchecked and unaccountable for the damage left in their wake.

In a live video on Twitter, Carcillo explained why he never told his parents about the hazing he was tormented by in junior. It’s because they would have done what any parent would do, he explained, and driven out to Sarnia to take him home and then his dream would have been over. Then he would never be an NHL hockey player.

— Daniel Carcillo (@CarBombBoom13) December 1, 2019

And so he would have done anything for his coach, he said, because he’d been trained since he was just a child to see hockey as religion, to believe that its blessings could only be handed down by the big men in charge. This is the key, the thing that not all who engage this debate feel comfortable exploring. The problem is systemic.

So out of this, a necessary truth: the NHL is not the game. Hockey Canada is not the game. The game does not belong to the institutions that build it for cash and glory, or the people at the helm of those institutions. These are the systems, as flawed and prone to failure as any other humans can create, and they are not the game.

The game is winter music. The game is red cheeks on brisk afternoons. The game is the flow of movement, eked out on sledge or skates and with varying degrees of speed and grace, but the joy of it remains the same. The game lives wherever kids find pucks and sticks.

If the institutions find ways to hold coaches and teams accountable for toxic environments, then more youths– whether destined for The Show or just playing for fun in their spare time — will come out of their training with their love for the game intact and ready to thrive.

And whatever change must come to the institutions, it will not dent the game.

And so hockey will not only survive the reckoning in the NHL and its feeder leagues, it will be better for it. If abusive coaches are held accountable, then there is more room for the good coaches to flourish, the ones who draw talent out of players with equal doses of respect as determination, the ones who inspire resilience and drive.

Above all, there is this: if the institutions find ways to hold coaches and teams accountable for toxic environments, then more youths — whether destined for The Show or just playing for fun in their spare time — will come out of their training with their love for the game intact and ready to thrive.

To get there will take more courage from more people. It will take a lot of introspection from those who could have done more to hold abusive staff accountable. It will take more voices speaking up to say — yes, there are these two words again — “me too,” and every time those voices are heard, they call down a little more light.

Shine on, shine bright. The NHL may have some problems, but the game?

The game will be all right.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.