Federal electoral reform under microscope once more

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/11/2019 (2234 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — Electoral reform advocates hope the other parties will push the federal Liberals to change how Canadians vote, arguing last week’s divisive regional split will only worsen under the current formula.

“We have a system that actually penalizes countrywide support, and rewards parties that have strongholds,” said Wilfred Day, national secretary of Fair Vote Canada.

The Liberals were re-elected last month with 33 per cent of votes — less than the Conservatives, and the lowest share recorded since Confederation.

Meanwhile, the Bloc Québécois is taking 10 times the number of seats as the Greens, despite earning just 1.19 per cent more of the national vote.

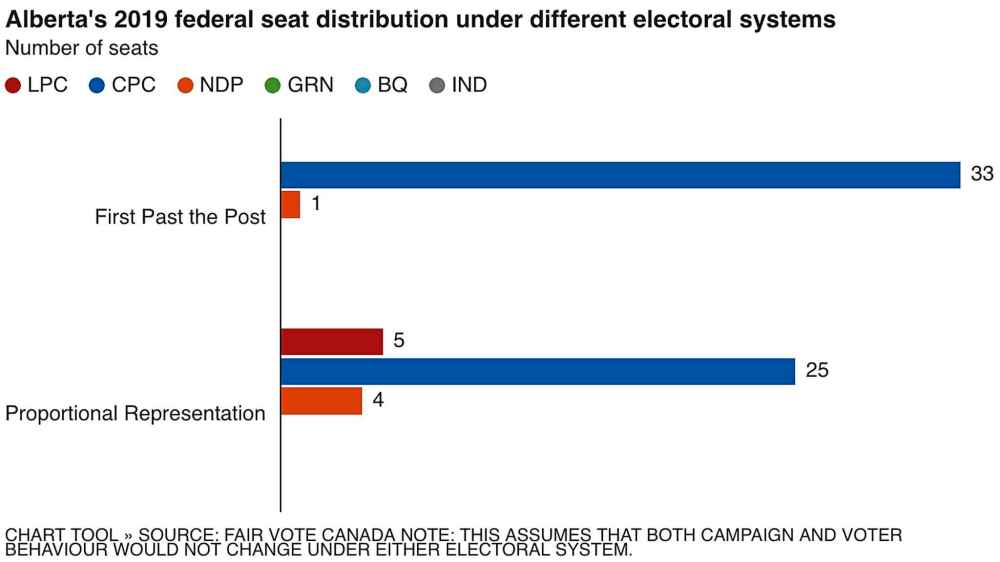

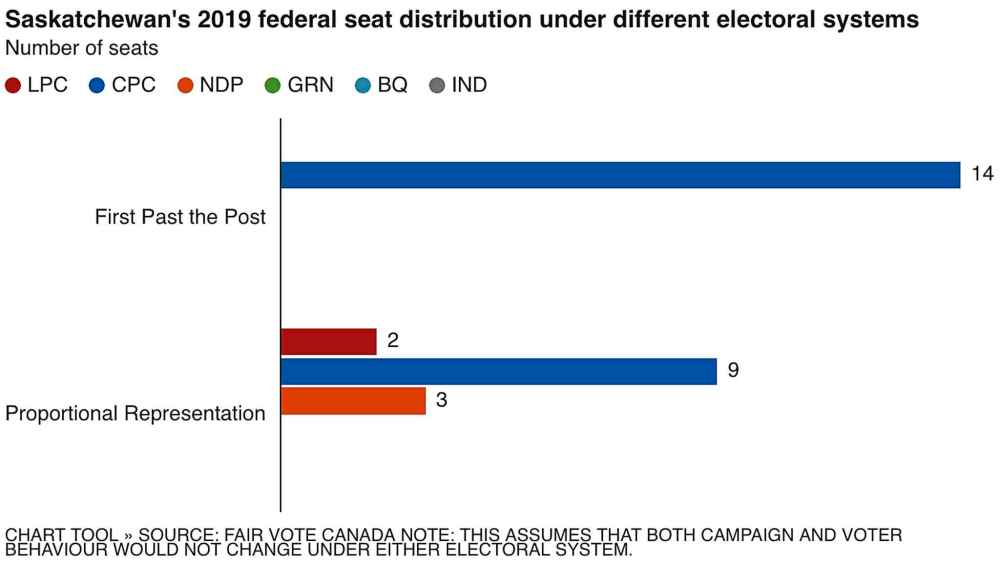

Alberta and Saskatchewan are frozen out of cabinet, after the Liberals failed to win a single seat in either province.

To Day, it’s a repeat of the 2006 election, when Tory leader Stephen Harper won a minority government without a single seat in Toronto or its surrounding municipalities.

“I think one is bad as the other,” he said, arguing it’s left to chance whether a region’s traditional party wins and thus has its issues highlighted in Parliament.

In 2016, a multiparty House committee recommended Canada switch to a form of proportional representation such as the mixed-member compensatory system. Like in Germany, voters would have a ballot for their riding MP, and one for their party, who would select MPs from a list to represent larger regions.

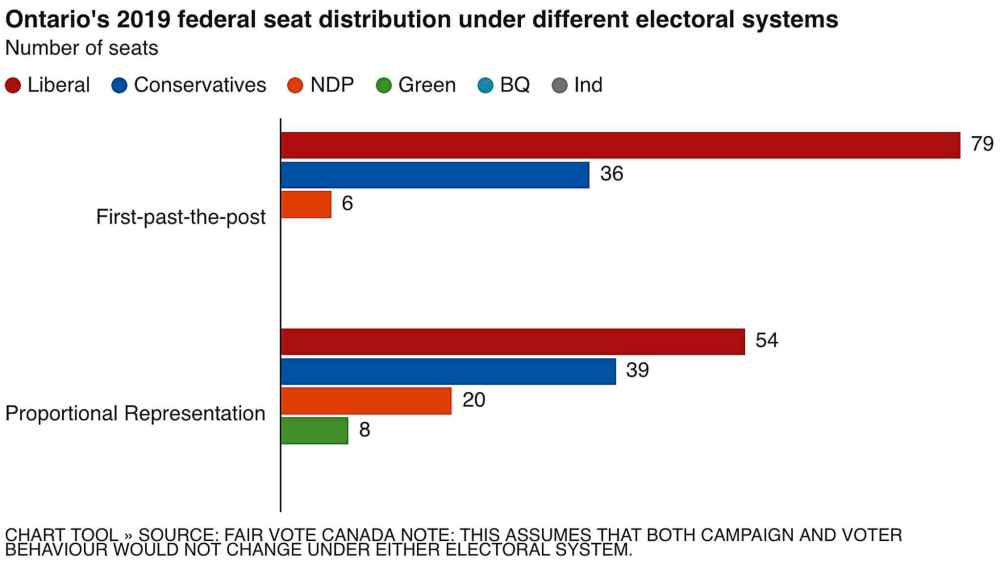

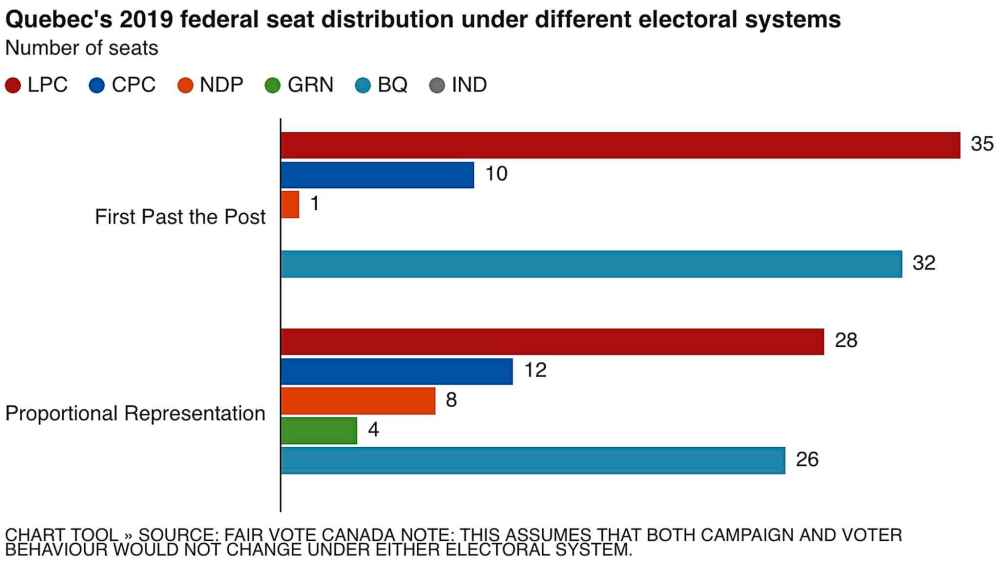

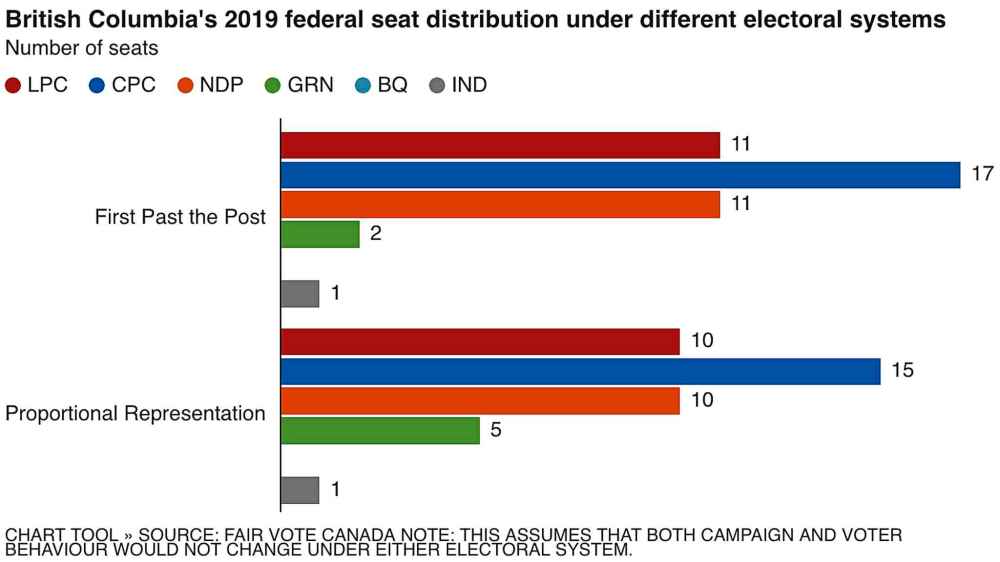

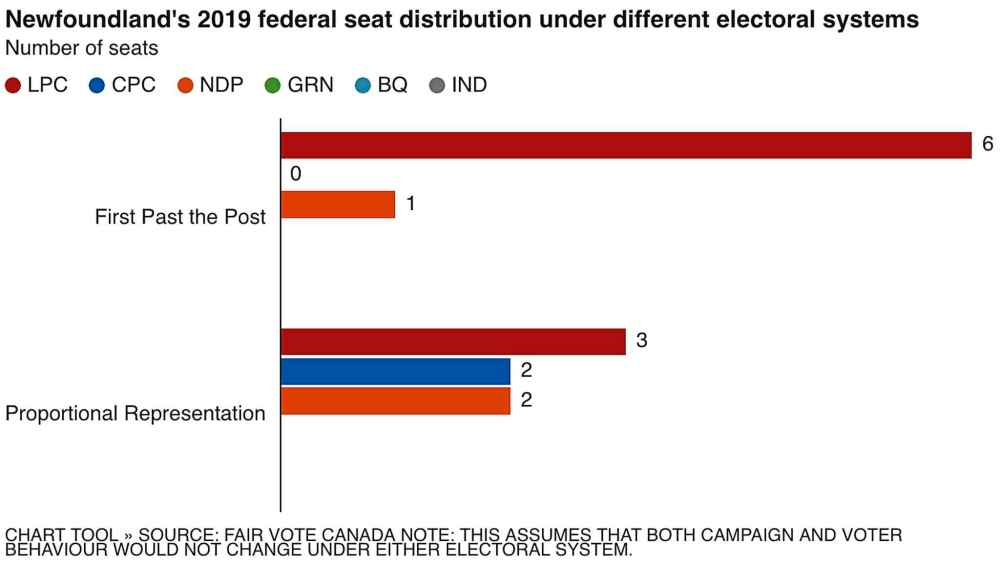

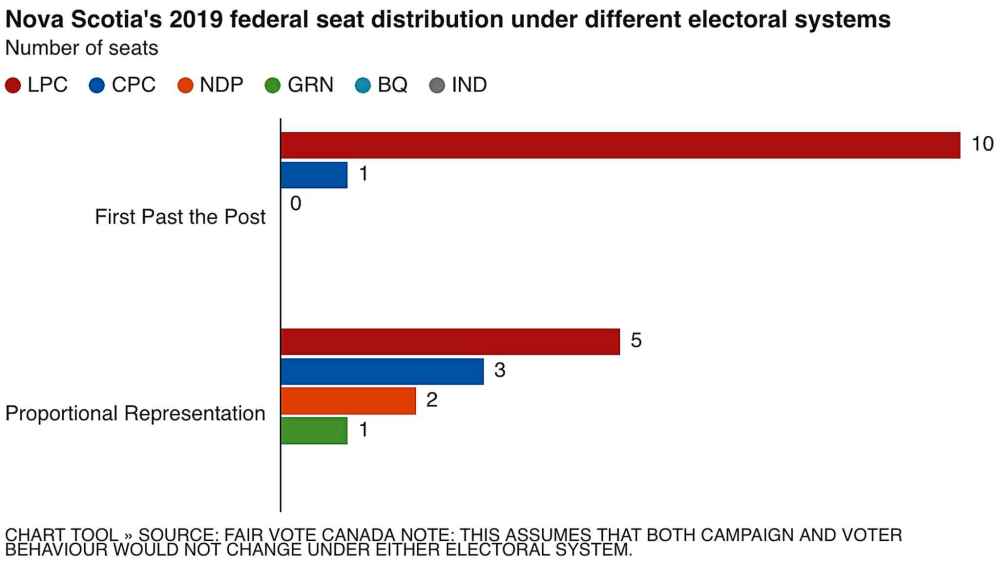

If last month’s results were applied to that system, the Conservatives would form government with slightly more seats than the Liberals — likely 118 Tory seats and 116 Liberal ridings, depending on regional weight.

The NDP would hold 56 seats instead of 24, the Greens would field 21 seats instead of three, and the Bloc would be taken down to 26 (from 32).

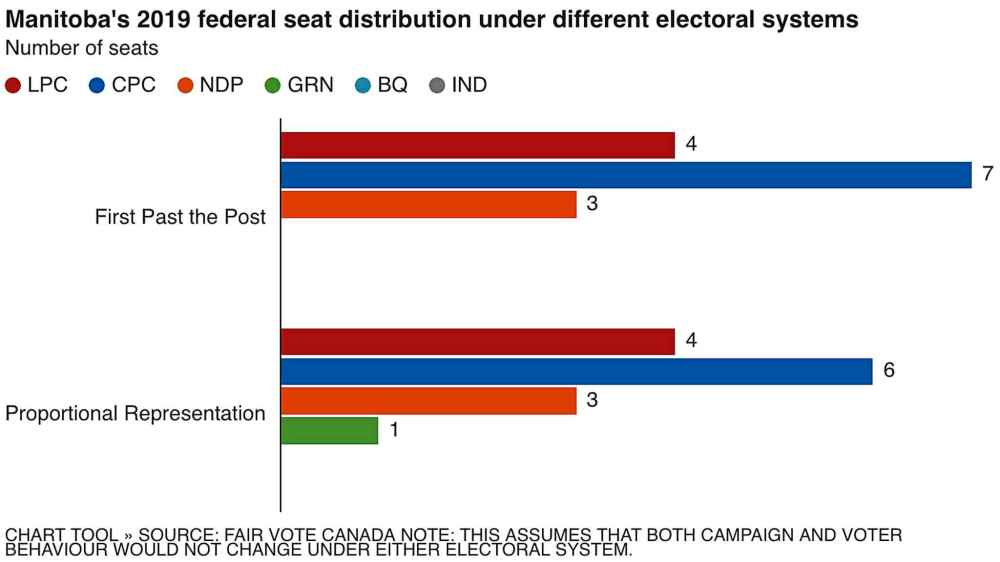

In Manitoba, where there are currently seven Tory, four Liberal and three NDP MPs, that would mean one less Tory seat, and one Green MP. The other Prairie provinces would have seven Liberals and just as many NDP MPs, while the Tories would still reign with 34 seats (instead of 47).

“Right now, we give a bonus to parties that are regionally concentrated,” Day said. He noted the 1993 election gave the Bloc official-opposition status, despite the Reform party winning more votes.

In 2011, Harper achieved a majority with just under 40 per cent of the vote, as did Liberal leader Justin Trudeau in 2015, “which gave them about 60 per cent of the seats — and 100 per cent of the power,” Day said.

In Harper’s case, he held just five of Quebec’s 75 seats, sparking concerns about regional representation. It led former Liberal leader Stéphane Dion to declare the existing system “weakens Canada’s cohesion” in a 2012 essay.

“I do not see why we should maintain a voting system that makes our major parties appear less national and our regions more politically opposed than they really are,” Dion wrote. “I no longer want a voting system that gives the impression that certain parties have given up on Quebec, or on the West.”

Day lives in a rural Ontario riding that, in 2015, elected a Liberal MP who supported electoral reform — likely due to strategic voting given a drop in support for the Greens and NDP compared with previous races.

Last month, that MP lost her seat to a Conservative by a small margin. If slightly more than half of Green voters in the riding supported her, she’d be returning to Ottawa.

Day believes many of those Green voters thought they’d be rewarded with a new voting system when they supported Trudeau in 2015, and went back to casting a ballot for the party they actually want.

“The Liberals broke their promise, and the broken promise came back to bite them,” he said.

Day noted Winnipeg North MP Kevin Lamoureux was a vocal proponent of proportional representation while an MLA for the Liberals, who struggle to gain provincial seats.

After reaching the Hill, he said he favoured a preferential ballot in which voters rank their choices, a system that benefits larger parties. When the Liberals failed to get buy-in from the other parties for such a system, they scrapped the idea of electoral reform entirely.

Yet, Day argues the Liberals have enough grounds to revisit the issue, on the premise the current system imperils national unity. He says they could save face by creating a citizens’ assembly of randomly-selected non-partisans to study different electoral systems.

David Herle, a senior Liberal strategist who runs the Gandalf Group polling firm, is unconvinced.

“I don’t think there is a legitimacy issue in the broad public about the government,” said Herle, who hails from Saskatchewan.

He argues the current system awards centrist parties that moderate their platforms to be the most widely attractive, and get support from as many regions as they can.

Under the mixed-member compensatory system, one of the main options studied by the parliamentary committee, Maxime Bernier’s fringe People’s Party of Canada would have won six seats. The existing system made sure none of the party’s MPs would be challenging climate science or calling for radical immigration reform.

“All the underlying schisms in Canadian society would be significantly exacerbated by proportional representation,” Herle said. “I don’t actually believe that would produce more legitimate governments.”

Herle said the Tories’ meagre results outside the Prairies shows the system rewards those who court voters in different regions, with a mix of urban and rural ridings.

So how much support does a party need to form government?

In the backrooms, he says, political staff largely ignore national polls unless a party is approaching 40 per cent support, which suggests a majority. Otherwise, staff are focused on polls at regional levels, such as parts of different provinces.

“If you’re running a campaign, you know what you need to do in various regions to get to the seats that you need, and that’s what you’re looking at.”

While the Tories gained more votes in October than any other party, they lost support in Canada’s two most populous provinces, especially in the key battleground areas near Toronto and Montreal.

Polling expert Philippe J. Fournier said he found some of the Conservative campaign bizarre, such as the day of massive climate-strike rallies.

Despite climate change ranking as the highest issue for most voters, Tory Leader Andrew Scheer shirked those rallies and instead made an announcement about widening highways, before flying to Edmonton where his party was widely expected to already win a few seats on top of its existing dominance in the province.

The Tories ended up with overwhelming support in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

“Those are basically wasted votes,” said Fournier, creator of the prediction site 338Canada.com. “This was a winnable election for the Conservatives.”

Fournier doesn’t have an opinion on electoral reform. But he noted last month’s result echoes the 1979 election, which ended with Conservative leader Joe Clark taking the most seats, despite losing the popular vote by four points, with the Liberals’ support concentrated in Quebec.

“It really is about regional distribution in this country,” said Fournier.

Typically, he said a party needs about 35 per cent support nationally in order to form a minority government, if the NDP is at is typical threshold of 15 per cent support.

But with the Greens and the Bloc gaining more support, it’s almost impossible to look at national polls and get a sense of who will form government, he said.

“It really is about regional distribution in this country” – Polling expert Philippe Fournier

“For me, if you get 40 per cent of voters to agree on something, you should be rewarded. But with 34 or 35 per cent, it seems there’s a psychological level coming into play, that two-thirds of the country did not vote for you.”

Within Quebec, the provincial government is debating implementing a proportional-representation system, but is facing outcry from rural regions such as Saguenay and Abitibi, over fears cities will dominate the legislature.

Similar worries about electoral reform have been raised at the federal level, where it’s unclear if Canadians will have another debate over changing how they vote.

“It’s not coming back soon, I think,” Fournier said.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Friday, November 1, 2019 7:02 PM CDT: Adds photo

Updated on Monday, November 4, 2019 9:10 AM CST: Clarifies references to mixed-member compensatory system