Lake Winnipeg needs us now

Ailing body of water gives life -- it's long past time to dive into saving her

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/08/2019 (2318 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Steadily this summer, Lake Winnipeg’s algae blooms have been growing.

This year saw some of the earliest emergence of blue-green algae blooms in the lake. The blooms coat shores with sludge, kill vegetation and suck oxygen out of the water — creating toxic “dead zones.”

It’s impossible to ignore our growing algae problem. Fish are dying or coalescing in pockets of “safe” water throughout the lake. Water consumption is becoming a problem for cottagers, evidenced by an advisory warning issued by the RM of Victoria Beach. Vacationers are migrating from Grand Beach’s goo-covered shores to swim in other parts of the lake, like Albert Beach. Blooms are now visible from space.

No matter how far we run from this problem, though, the truth is this: algae is slowly killing Lake Winnipeg.

For four decades, algae has been steadily increasing in Lake Winnipeg. While some algae is necessary for life, large toxic blue-green algae blooms are caused by nitrogen and phosphorus from sewage, fertilizers and pesticides draining into the Lake Winnipeg watershed.

Simply put, Lake Winnipeg is like a giant funnel where the waste and products from seven million people across four Canadian provinces and four American states end up. That water is supposed to drain into Hudson Bay — but is blocked up by hydro dams along the way.

This all goes to produce a stagnant water system, ripe for algae production.

There are some proposed solutions. The Lake Winnipeg Foundation and the International Institute for Sustainable Development are proposing a chemical called ferric chloride to reduce the levels of phosphorus in Winnipeg’s north end water-treatment plant (which treats nearly 70 per cent of our city’s waste). It’s an exciting idea, but suffers from a lack of political co-operation as the city and province argue about how it will be done.

The problem is that even if ferric chloride or another strategy works at the north-end plant, the effects on algae in Lake Winnipeg would be a fraction of that produced from the rest of the watershed.

Restoring the natural filtration marshlands system, which absorbs nutrients and pollutants before entering the lake, is the most effective solution. A coalition of academics, politicians and groups is beginning a small project this summer to restore parts of the Netley-Libau marsh. This is the most cost-effective and sustainable solution, but suffers from a lack of widespread support.

The real issue with stopping the rise of algae in Lake Winnipeg is convincing two national governments, eight provincial and state legislatures, and thousands of private and public organizations that algae is a problem that needs addressing. Voters and citizens simply don’t take the problem seriously and the few voices telling them aren’t being heard.

Lake Winnipeg, of course, is telling us all there is a problem, but no one listens to her.

The only solution is seeing Lake Winnipeg for what it is: life.

Lake Winnipeg is not just at the heart, but is the heart of North America.

Virtually everything flows in and through it: from food to water to people.

Like healing a toxic, sick body, medicine must come from its centre for all the extremities to survive and thrive.

It’s time we recognize the life of Lake Winnipeg.

Rallied by Indigenous nations and leadership, governments across the world are increasingly recognizing waterways and spaces as carrying the life force in communities.

And what defines life in society? Rights.

In India, the Ganges River was recently given rights on par with those that people enjoy. Ecuador’s constitution dictates that nature “has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes.” This means that anyone can demand Ecuadorian authorities protect and enforce the right of nature to live like any other being. This defines polluting, therefore, as not just an inconvenience but a punishable destruction of life.

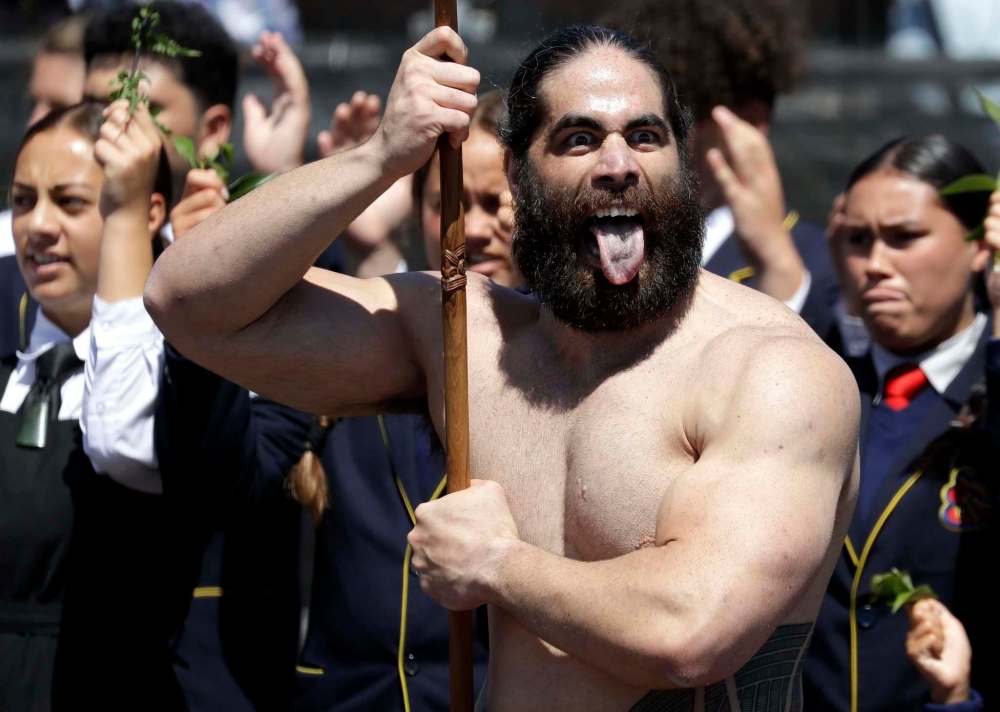

In New Zealand, the Maori successfully convinced authorities to make the Whanganui River a “person” under domestic law. The river is a part of their creation story — a sacred site of life. The decision means that anything affecting the flow, shorelines and watershed of the Whanganui River must be legally considered by a committee of government and Indigenous representatives.

Recognizing waterways as beings with rights is not crazy. We do it for corporations. Today, businesses and people have more rights than nature — which I would suggest is what got us into this Lake Winnipeg mess in the first place.

In terms of contributing to our community, by the way, I’ll take Lake Winnipeg over any corporation, government or citizen.

Lake Winnipeg has given us more than we could ever give back.

Now, it’s time to help her.

Declaring Lake Winnipeg a being with rights would be simple and, for the first time in North American history, legally recognize a relative who has taken care of our families, our food and our water.

Declaring Lake Winnipeg a being with rights would ensure that every single government, legislature and business affecting the lake would have someone to answer to.

And declaring Lake Winnipeg a being with rights would ensure someone — somewhere and somehow — would be advocating, defending and fighting for it. Right now, it’s just something Indigenous Peoples, a few interested organizations and some volunteers are doing.

Lake Winnipeg is dying and we can do something about it.

It’s the least we could do for a relative and, in the end, we might even save ourselves.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, August 6, 2019 6:46 AM CDT: Photos added.