Moving forward Yoga helped Winnipegger heal, inspire others after nightclub assault led to traumatic brain injury — and long road to recovery

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/06/2019 (2378 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

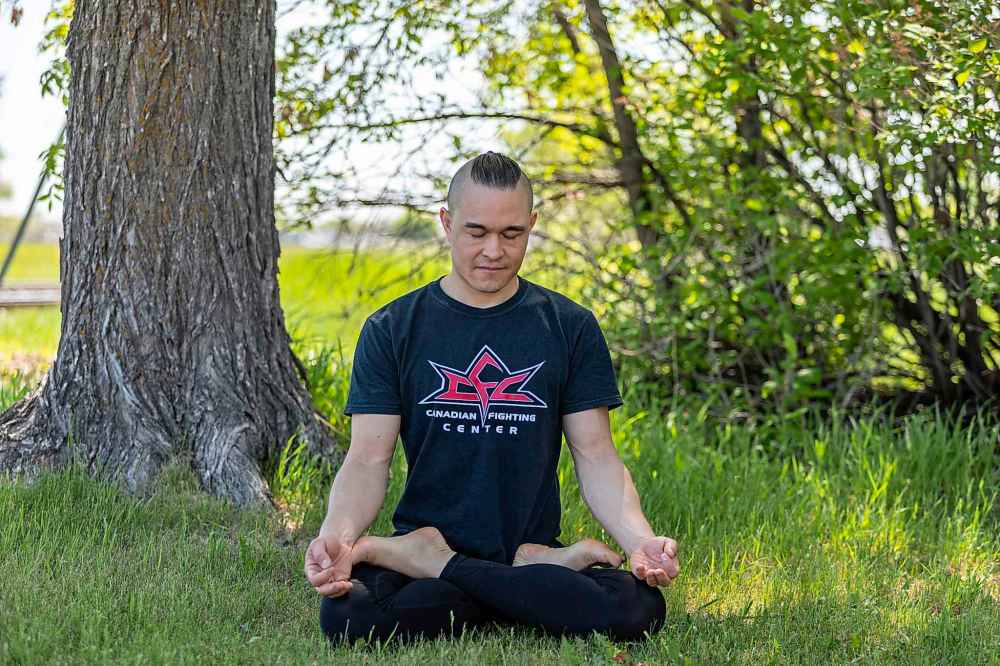

Nearly a decade after a traumatic brain injury changed his life, Derek Pang has yoga to thank for both his physical and mental recovery.

In May 2010 at age 26, Pang was assaulted in a Winnipeg nightclub and sustained a severe traumatic brain injury that left him unconscious with a fractured skull. He was in a coma for three-and-a-half days and suffered post-traumatic amnesia.

“I didn’t remember anything for over a week,” he says. “I was strapped into the hospital bed because whenever I woke up, I freaked out and tried to escape. I didn’t know where I was.”

As a lifelong athlete, Pang had suffered concussions in the past; he grew up playing soccer and hockey and holds a brown belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu. He trained for several years out of Winnipeg’s Canadian Fighting Centre on Archibald Street and had experienced several blows to the head as a mixed martial artist.

Pang spent the next two months as an out-patient at Riverview Health Centre. He dealt with bouts of anger, impulsivity, isolation, short-term memory loss and had difficulty reading. He also spent time with a speech language pathologist.

Gladys Hrabi, executive director of the Manitoba Brain Injury Association, says it’s common to feel anger and grief following a brain injury.

“Anger could be out of frustration of not being able to do things as well as you used to,” says Hrabi. “As part of the recovery process, you may need to accept that you will not be the same person you were before the injury and you may experience grief over this loss. This is normal and no cause for shame.”

Following his injury, Pang had a different outlook on life.

“When I woke up in the hospital, I had all these new realizations,” Pang says. “Everything that I thought was important before — what you look like, what other people think of you — that meant nothing.

“When you’re on your deathbed, none of that matters.”

The consequences of a concussion and other traumatic brain injury can be severe, especially for children and youth. Brain Injury Canada says 160,000 people suffer from brain injuries annually and approximately 1.5 million Canadians live with the effects of an acquired brain injury.

Hrabi says they can happen to anyone.

“A brain injury doesn’t discriminate,” says Hrabi. “It has no cure so someone with a brain injury has to live with the long-term consequences for the rest of their lives.”

Once out of his coma, Pang felt an immediate sense of forgiveness for the people who assaulted him.

“The people that did that to me, they may not even know I’m alive. I realized I could feel sorry for myself or move forward — it’s one or the other,” he explains. “All we have is the now. When you hold onto the bad stuff, the only person you harm is yourself.”

Pang had a long road to recovery and says anger weighed him down and took a toll on his emotional energy.

“I had enough things to worry about and overcome,” he says. “I didn’t need more chains to pull me down. I realized I could let go because it didn’t serve me.”

Following the incident, Pang took an extended break from mixed martial arts. Accustomed to daily physical activity, he had to search for a different physical challenge — and one that didn’t involve contact.

“Growing up playing soccer and hockey, my whole identity was being an athlete,” he says. “I didn’t know how not to be active.”

Pang discovered Bikram yoga, a form of hot yoga performed in an environment of 40 C. As a natural competitive athlete, Pang went into his first class thinking it would be a breeze.

“At the end of class I thought, ‘This is yoga?’ It was the hardest thing I’d done, both physically and mentally,” he says.

Pang was hooked. He did Bikram yoga every day for a year.

During his recovery, Pang used yoga as his primary means of healing. The following months of commitment and regular yoga practice helped him recover from his injuries and improve not only his physical conditioning but also his mental health.

Pang also stressed the importance of nutrition, sleep, physical activity, meditation and surrounding yourself with a strong community. He believes these self-care strategies were paramount in his recovery.

“Life is about the ups and downs. When you’re experiencing a low point, the more life tools we have on our belt, the quicker the bounce back will be,” he explains.

“When we’re down, it’s hard to start learning new strategies that will help us overcome what we’re going through.”

Passionate to inspire others with the power of yoga, Pang created The Hero Project, a school-based mindful breathing, mobility and movement classroom initiative.

“I’m on a mission to uplift, inspire and empower students to become their best selves,” he says. “The HERO Project is about how bringing attention and awareness to our breath, posture, choosing to smile and being present can influence the way students navigate their reality.”

Almost a decade later, Pang has fully embraced yoga and a holistic lifestyle, including physical, mental and spiritual health. He’s back training at the Canadian Fighting Centre, has completed more than 400 hours of yoga training, including his most recent certification as an animal flow instructor. He’s also a certified Onnit Academy trainer, which is a fitness facility based out of Austin, Texas.

In 2014, he completed his bachelor of social work at the University of Manitoba (he also holds a bachelor of commerce honours degree.)

Pang is also trained in LoveYourBrain Yoga from the LoveYourBrain Foundation, which provides awareness about brain injury prevention and healing. This yoga is designed to support people who have experienced a traumatic brain injury and their caregivers. The yoga and meditation series is designed based on the science of resilience.

June is Brain Injury Awareness month across Canada. For Pang, 35, yoga and his daily practice were his saving grace.

“It’s important to recognize the significance of forgiveness and the power of choice,” he says. “I learned this from my yoga practice.”

The time and effort Pang put into his self-care toolbox guided his recovery. Human beings are resilient. Through perseverance and dedication to his practice, Pang was able to heal both his body and mind.

Sabrina Carnevale is a freelance writer and communications specialist, and former reporter and broadcaster who is a health enthusiast. She writes a twice-monthly column focusing on wellness and fitness.

sabrinacarnevale@gmail.com

@SabrinaCsays