Stories left untold

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/05/2019 (2078 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“For all that has been written on women’s actions during the Winnipeg general sympathetic strike of 1919, it could be concluded easily that females were not there at all, that they passed the six weeks holidaying at Lake Winnipeg.” That was the opening line of my 1986 undergraduate essay published in Manitoba History.

In the early 1980s, as a history student at the University of Manitoba, the first big lesson I learned was that everyday people can change the course of history. Soon after that, I learned my second big lesson — even though women have always made up roughly half of the population, we don’t often make it into the history books.

When I first began studying history, there was only one female professor in the department, Mary Kinnear. Not only was she the only female faculty member, but she was also the only one teaching women’s role in history. During the first course I took with Kinnear, she asked students to choose a historical event and uncover women’s participation. I picked what might be considered the most famous event in Winnipeg’s history: the 1919 strike. But after spending weeks reviewing all the published work on the strike, the paper I handed in described how I couldn’t write about women and the strike because there was no information. Kinnear returned my paper and sent me off to the archives.

At the Archives of Manitoba, I pored over census reports and spent long hours peering at scratchy film reels of newspapers in the dim light of the microfilm room. I pulled photos from files and scrutinized images of crowds gathered on Main Street and Victoria Park. There, in these basic sources, were the answers. Women made up almost 25 per cent of the paid workforce in 1919 and were involved in every aspect of the strike.

“Women acted as strikers and scabs, rioters and terrorists,” I wrote in my university essay. “They made coffee and sandwiches for striking workers, and they struggled to piece together a meal for their families. Women as strikers unplugged the telephone lines and women as scabs plugged them back in. Women took to the streets during riots, they terrorized scab labour, and one woman has been credited with the infamous act of setting fire to the streetcar on Bloody Saturday.”

Kinnear then invited me to submit my essay to a special issue of Manitoba History that she was guest-editing on the topic of women’s history. When my article was peer-reviewed by a male historian before publication, he excitedly asked me where I had found this information. It struck me as odd that the question was where I found this information. The question should have been: how did all the other much more experienced historians fail to see this information about women? After all, it was in all the most standard sources at the archives.

Newspapers from 1919 spell out women’s varied roles in the strike. On May 15, 1919, the strike was officially scheduled to begin at 11 a.m. But at 7 a.m., 500 telephone operators left their shift and no one came in to replace them. Ninety per cent of these workers were women, and thus, women showed the courage, determination and faith to walk out before anyone else. Newspapers also describe the role of women trying to make meals for their families during the strike with limited food, the role of women as volunteer labourers (less charitably known as scabs) and as fierce protagonists no matter what side of the strike they aligned with.

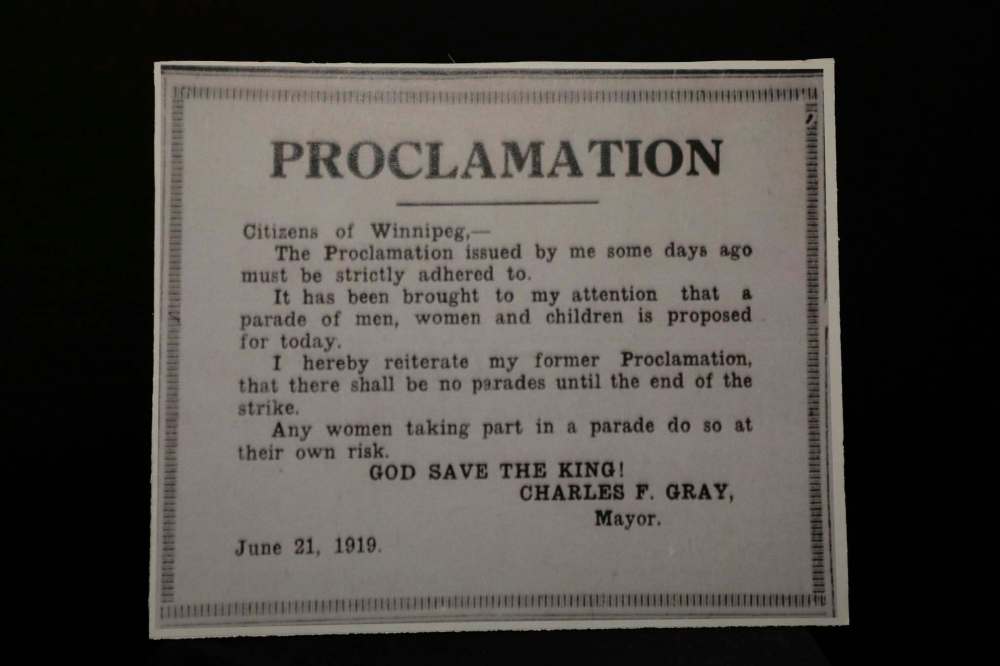

One newspaper report described the women of the Brooklands and Weston neighbourhoods who wrecked three delivery trucks and assaulted not only the drivers but even the police who had been sent to protect the drivers. One policeman reported that he “wouldn’t advise any man to go out there” and risk being caught working during the general strike. Throughout the strike, several women, including strike leader Helen Armstrong, were arrested on charges of assault and disorderly conduct. Even mayor Charles Frederick Gray, on June 21, made special notice of women in a proclamation warning strikers and supporters off the streets.

Almost every archival photo of a crowd shows women among the throngs. Often, the women are wearing long white dresses and big-brimmed white hats and stand out among the dark suits of the men. Another photo at the Archives of Manitoba shows two women dressed in pants, tall boots and jackets, operating gas pumps as volunteers. Sure, these women are likely scabs, but don’t they look strong and sassy!

The oral history tapes, photographs and newspapers in the archives underlined the prevalent discrimination against the “alien enemy” and described both the fears and strengths of immigrant women. These archival records also described with sympathy the dire straits that forced some workers, including women, back to work during the strike.

My 1986 article took the first sweep at the story of women’s involvement in the strike, and in that way broke new ground, but it was not inclusive enough. David Russell, a descendant of one of the strike leaders, said in an oral history interview: “There were people involved who were never mentioned, you know.”

New work from historian Adele Perry examines the relationship of Indigenous dispossession of land to the 1919 strike and the building of the Winnipeg aqueduct (the other significant event of 1919). As another example, the forthcoming movie of the strike by Danny Schur, whose musical has done much to popularize this story, will include a Métis war veteran and a black domestic worker from Oklahoma. A recent conference commemorating the strike included a session on disability and labour history. These are some of the ways that the story of the strike could more fully express the diverse stories of Winnipeg, become more meaningful to us all and unite us to build a better future.

This leads to my third big lesson learned about history: the importance of archives. If we do not have access to the historical material, we cannot craft the stories. We are fortunate Winnipeg archives have supported the centenary of the strike with initiatives that have greatly improved the ease of research.

The University of Manitoba Libraries, in collaboration with a number of other archives, launched a digital exhibit on May 15 that includes an extensive and impressive list of archival resources. The City of Winnipeg Archives has created a 24-page guide to its records relating to the strike. Resources at many archives can be searched online through the Manitoba Archival Information Network (MAIN) database supported by the Association for Manitoba Archives. As well, the University of Manitoba Libraries hosts digitized copies of all the strike newspapers on its website and the 1921 census that I used in my research is now available online.

However, we also need better access to the records — except for the small percentage of records that is digitized, archives are inaccessible to the public outside of Monday-to-Friday business hours. We need archives that provide access at least one evening and Saturday. Further, it is unacceptable that our own municipal archives have been relegated for the past six years to an inadequate building described as a “metal shed” in an out-of-the-way industrial park.

If we want our archives democratized so that we can tell our diverse and complex stories, it is vitally important that we ensure our archives are stocked with the records of all of our experiences — written, photographed, told, sung, painted, sewn and created by all of us. This valiant effort, unfortunately, will be hampered by the fact that all the major archives in Winnipeg have already reached a crisis level in storage capacity. In 100 years, if humans still exist, will we find anything in our archives to tell how we marked this centenary? What will be there to tell future generations about how we chose to move forward from today?

In the commemorations of the 1919 strike, it is gratifying to see that some of the stories of women’s involvement are now becoming commonly recognized. The purpose of describing historical events is not just to more fully understand our past, but also to understand our present situation and to help shape what is to come. Let’s stop telling the same old stories and do the necessary work to create new stories for a better future.

Mary Horodyski is an archivist, researcher and writer.