Our mother who art in journalism Pioneering, powerhouse turn-of-the-last-century Free Press reporter remains a north star for every Canadian woman who followed her peerless footsteps

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/05/2019 (2409 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

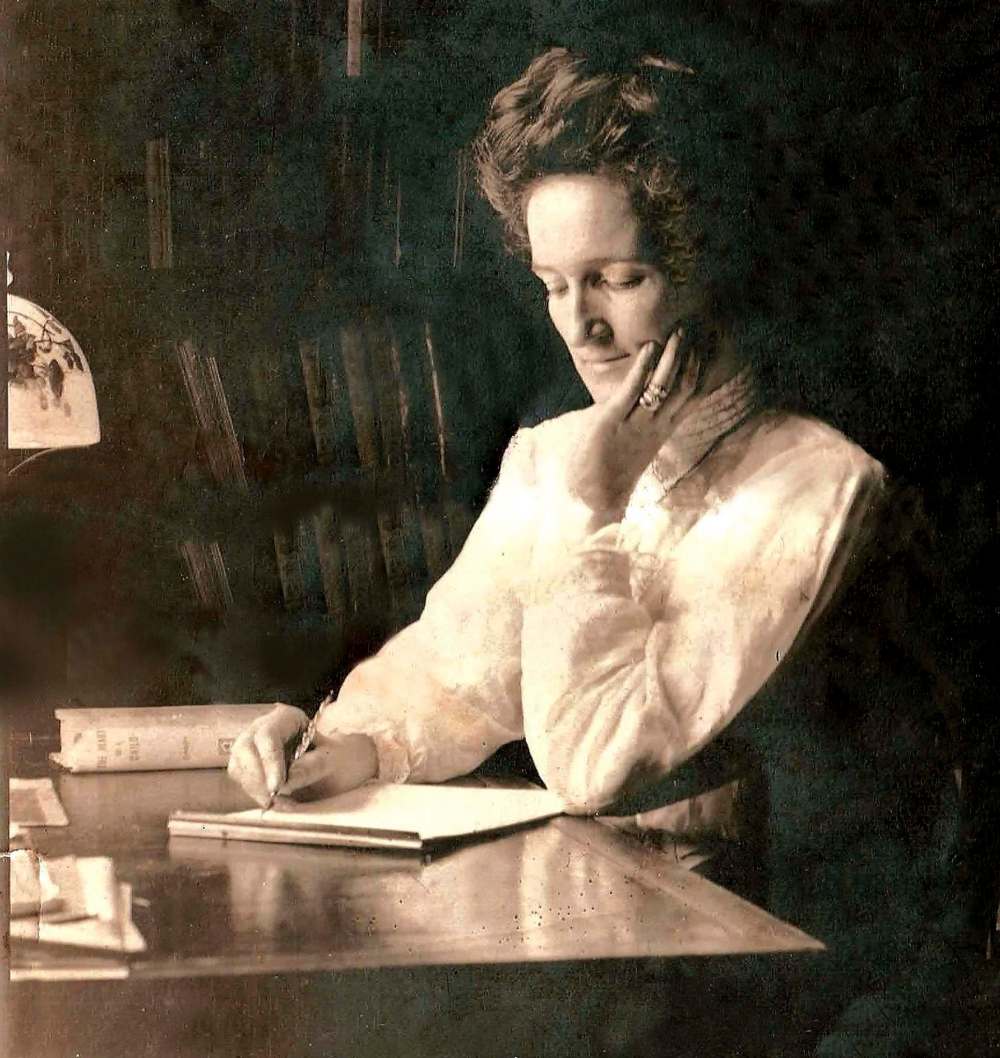

If she had some heavenly view of that night, and that room in Toronto, maybe Ella Cora Hind would have been smiling. The iconic Free Press journalist has been gone nearly 77 years, but her name still reverberates in the newspaper industry, and last Friday it rang out again on one of our most notable stages.

Among the 22 categories at the 2018 National Newspaper Awards (NNAs), one was named in her honour: the E. Cora Hind Award for Beat Reporting. Sponsored by the Nellie McClung Heritage Site, it was bestowed on the category’s lone female finalist: Globe and Mail journalist Zosia Bielski, for her work delving into issues of gender and discrimination.

While the beat category has existed since 2002, this year marked the first time that the awards have featured name sponsorship. It’s a change born partly in response to the industry’s tough economic climate, but it’s also a nice touch; newspapers have many departed greats. It seems right to connect their legacy to the work that is ongoing.

But those greats are also, to put it delicately, a fairly homogenous bunch. Indeed, of this year’s seven sponsored awards, six were named after men. It just so happened the Free Press had the perfect candidate to include a female legacy, and that the Nellie McClung Heritage Site had a unique connection to her story.

The choice of category was fitting. Few journalists in the early 20th century knew their beat as well as Hind knew agriculture. She was relentlessly analytical, with a head for figures that few peers could touch. On the Prairies, she was considered essential reading by farmers and traders, famed for her accurate crop yield predictions.

So significant were her contributions to agriculture in Manitoba that, when she died in 1942 at age 81, the Winnipeg Grain Exchange paused trading for two minutes to honour her life. For years, her name graced a scholarship and a research award. The impact she had on agricultural knowledge in the province can’t be overstated.

Meanwhile, Hind was also a role model for young Manitoba women. She was an outspoken suffragist and, along with Nellie McClung, one of the founders of the Political Equality League that won the vote for non-Indigenous women in 1915. But before that, she was one of McClung’s own idols — a female journalist with a fearless voice.

In her 1935 autobiography, Clearing the West, McClung devoted a chapter to the first time she saw Hind, who paid a visit to Manitou, where the Nellie McClung Heritage Site now sits. McClung rushed to the train station, hoping to catch a glimpse of Hind. She was nearly in awe when she did.

“I had seen her!” McClung wrote of that first sighting. “I had seen what a newspaper woman could be at her shining best. Like the sad little girl of whom Katherine Mansfield wrote in the Doll’s Playhouse, I could say, ‘I seen the lamp.’”

Yet for all the renown she drew during her career, Hind had not had an easy path into journalism. She had grown up on a farm in Ontario, a hardscrabble life. She studied to be a teacher, one of the few jobs open to women at the time.

When she moved to Winnipeg in 1882, she quickly applied for a job at the Free Press, which was marking its 10th year of publication. Her application was rebuffed. The paper’s first editor, W.F. Luxton, told her that the newspaper business was “no place for a woman,” especially one without journalism experience.

Instead, Hind became a typist, though she never stopped pushing to get into journalism. In 1901, she became the agricultural editor at the Free Press and, at the same time, the first female journalist in Western Canada. She would work for the paper for decades, and even travelled the world at age 75 to observe grain production up close.

The trail she blazed would eventually become well-trodden: it’s notable that many post-secondary journalism schools now report that a majority of their graduates are women. Yet if Hind’s legacy lives now in the name of the NNAs’ beat reporting honour, that fact also underscores that the work she began is far from over.

Of individuals named as finalists at this year’s NNAs, there were 24 women and 54 men. What is worse is that the finalists were more gender-diverse than they were diverse in any other way; Free Press columnist Niigaan Sinclair, who was named best columnist, appears to have been the only Indigenous journalist nominated.

Those numbers reflect where the newspaper industry has been. They should not reflect where it is going. Because what E. Cora Hind so deftly showed, decades ago, was that newspapers better serve their readers when a broader range of perspectives is included; imagine what would have been lost had she never had the chance.

Still, if she had been able to look down on that night in Toronto, maybe she would have been smiling. Because times have changed. Nobody would now say that journalism is no place for a woman. Even more, on one of the industry’s most sought-after stages, her name was used to honour work that centred on gender discrimination.

To even write about that in a newspaper would have been unimaginable in her day. To name the ways that women faced discrimination would have been unremarkable at a time when it was perfectly acceptable to say that gender alone was a disqualifying factor for the work of reporting a community’s stories.

So, we keep facing forward, knowing that the work Hind helped launch at this paper — and, by extension, Canadian journalism more broadly — is not yet finished. And believing that, by recognizing where that journey started, we can see a clearer route for the part that lies ahead.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.