Winnipeg’s civil war Tens of thousands of Winnipeg workers walked off the job for six weeks in 1919, sparking a pitched battle waged across economic, class and geographical lines, many of which remain

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/05/2019 (2412 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

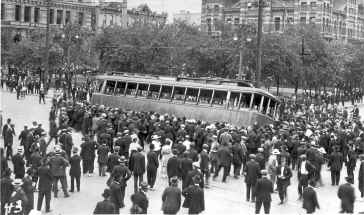

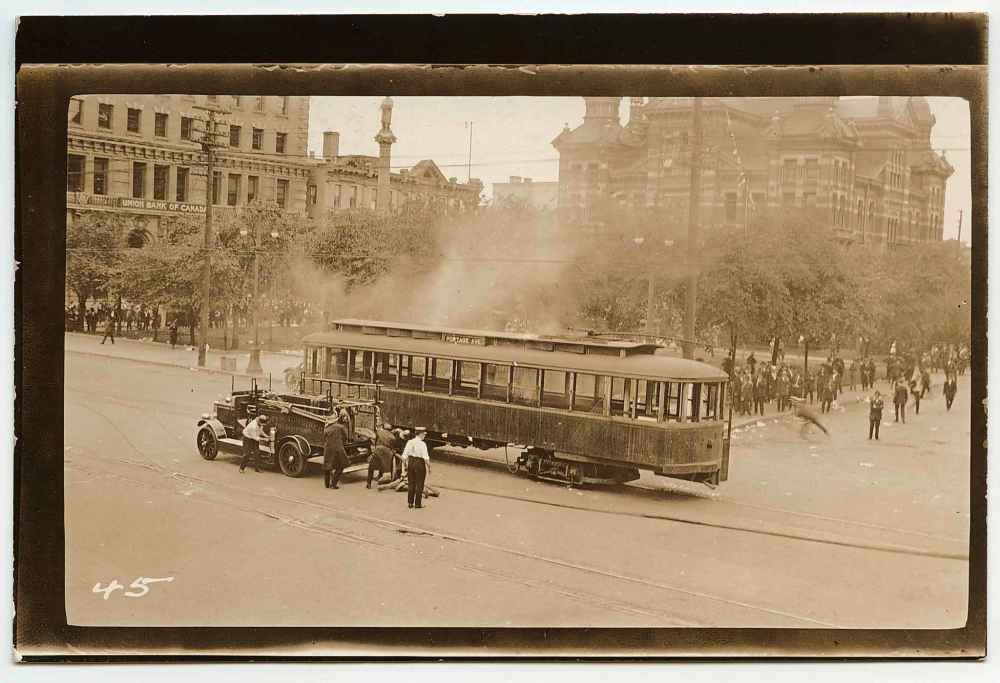

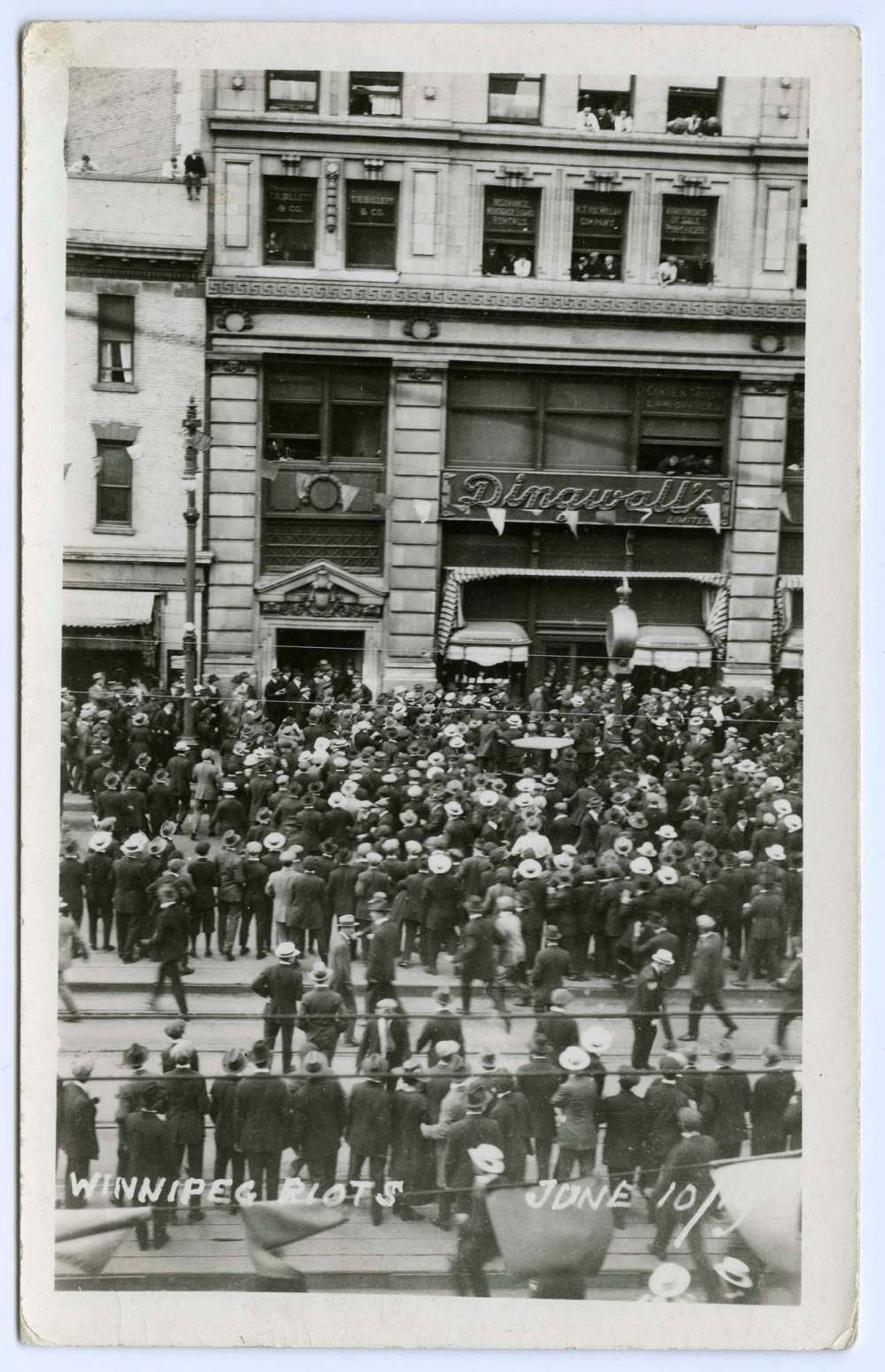

At about 2:20 p.m. on June 21, 1919, a lone streetcar rattled down Main Street toward Portage Avenue with a few passengers aboard.

There was nothing to suggest it would trigger events leading to monumental social and legal changes for generations to come in Winnipeg and well beyond its borders.

A horde descended to block the streetcar’s path. In their anger, they rocked it off its tracks and set it aflame.

A century later, the indelible image is a part of the city’s DNA; the defining moment of the Winnipeg General Strike, the greatest labour movement in Canadian history.

How the events unfolded

March 1919 —In Calgary, union leaders from across Western Canada rallied around the idea to form One Big Union. The convention spurred conversations that ultimately influenced the Winnipeg general strikers about two months later.

May 1-2 —Members of the Winnipeg Building Trades Council and the Metal Trades Council went on strike. Employees at Vulcan Iron Works, who manufactured railway parts, and those from Manitoba Bridge and Dominion Bridge had previously struck in 1917 and 1918 as well, decrying long work hours, low wages and awful working conditions. They also wanted access to collective bargaining.

To understand the unrest and upheaval is to understand what Winnipeg was in 1919. Thousands of victorious soldiers had just returned from the Great War to a city beset by sky-high unemployment and runaway inflation. Their celebratory homecoming was short-lived, they were dismayed to find newcomers to Canada in jobs they’d abandoned to join the war effort. The poverty-stricken immigrants “lucky” to be employed worked long hours in deplorable conditions for meagre wages.

Overseas, the success of the Russian Revolution two years prior and the rise of industrial unionization fuelled hope for a new labour reality here, Canada’s third-largest city at the time and its industrial rail nerve-centre.

Those hopes quickly collided head-on with the city’s established status quo. The clash of ideas became a class war fought across geographical lines: the moneyed elites and factory owners living in mansions along Wellington Crescent and throughout Crescentwood to the south holding fast against the working poor and unemployed surviving in squalor in the city’s north.

The Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council fired the opening volley on May 15, calling a general strike after negotiations between management and workers in the building and metal trades broke down. The workers were demanding the opportunity to collectively bargain for better wages and improvements in working conditions.

In under two hours, more than 30,000 workers — men and women in both private and public sectors — walked away from their jobs. Commerce, transportation and public service ground to a halt.

Little did they know then the walkout would set the stage 38 days later for the bloody, deadly conclusion that still reverberates through organized labour negotiations to this day.

Rising temperatures, rising tensions

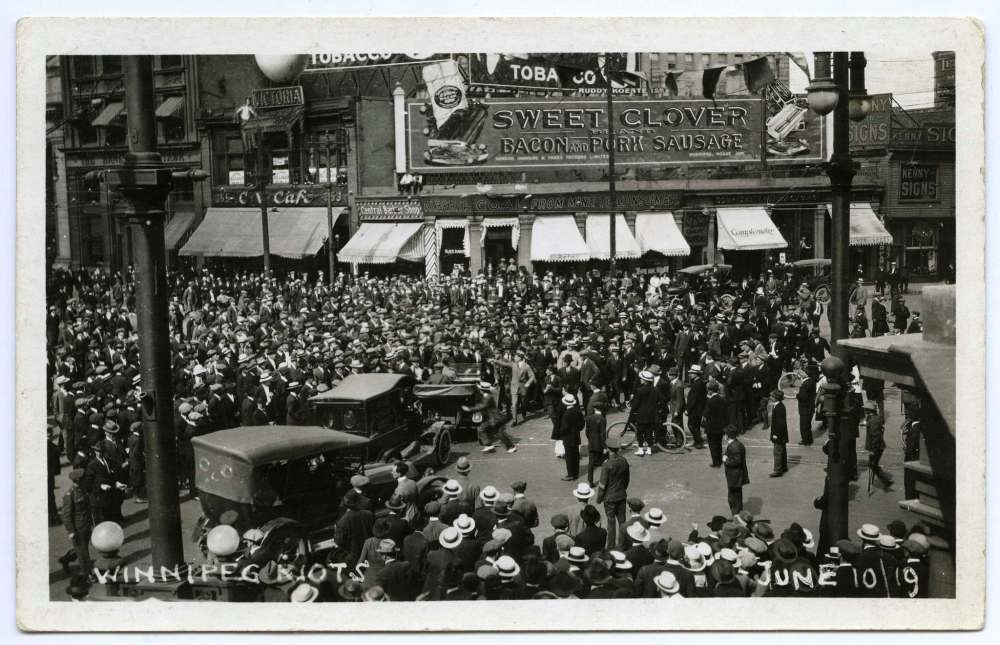

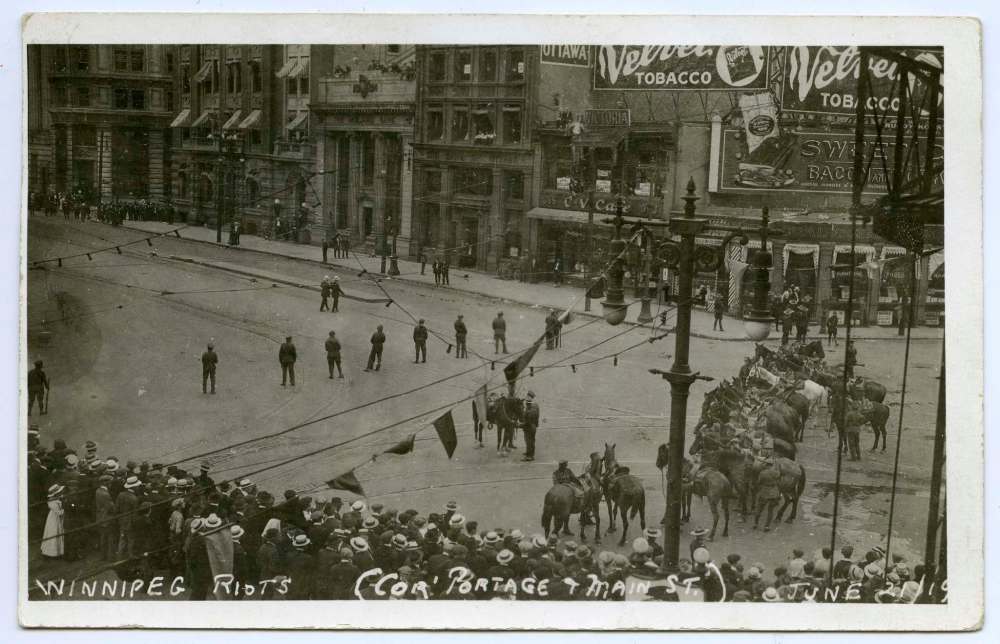

Winnipeg was in the middle of a heat wave on June 21, 1919. The forecast high was 30 C, but the temperature on the street had reached the boiling point.

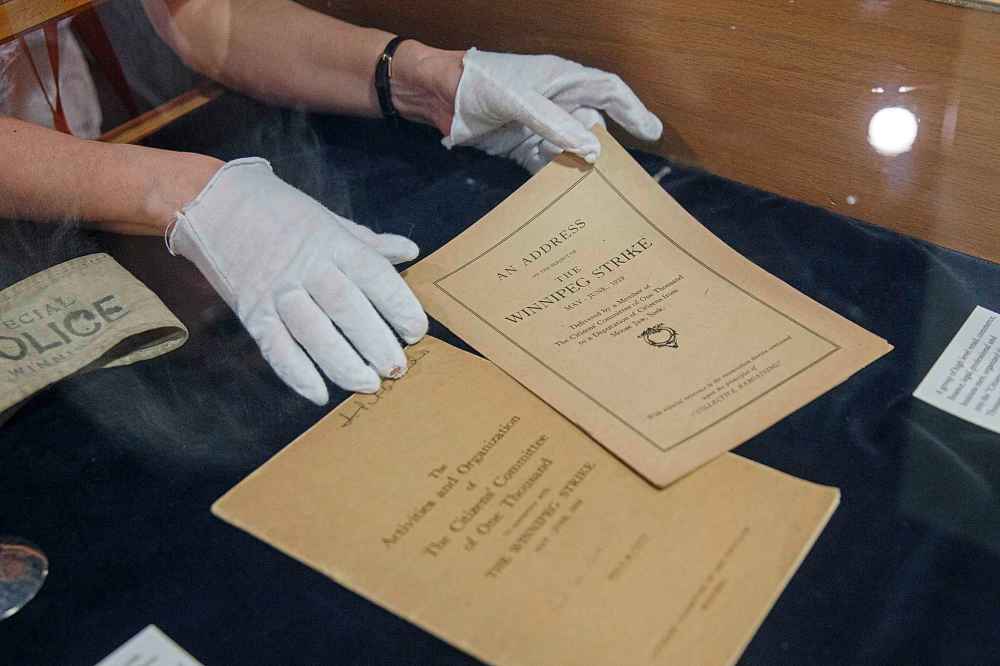

Every move made by the workers, led by the Central Strike Committee composed of representatives from each union affiliated with the WTLC, was countered by the business elite’s Citizens’ Committee of 1,000, which had the support of all three levels of government — including the military — along with the city’s daily newspapers.

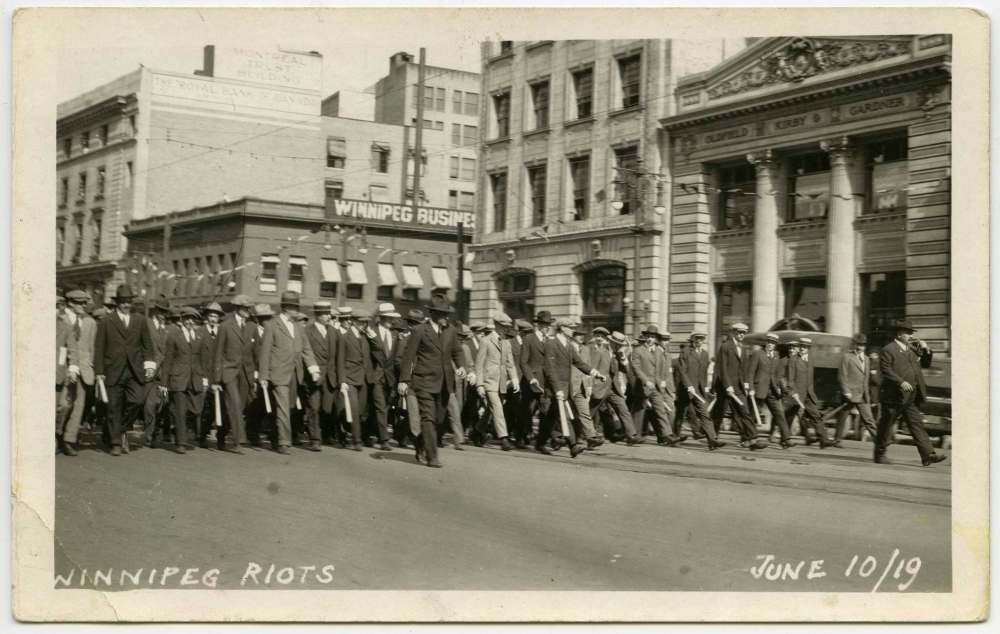

There were marches at the legislature and massive rallies at Victoria Park in the East Exchange along the Red River. Delivery drivers were prevented from entering neighbourhoods if they didn’t display strike committee-issued permission cards. In a bold move, strikers took their protest to employers’ homes on Wellington Crescent; the action led to a proclamation from the mayor banning further marches, but the strikers were not deterred.

Meanwhile, the citizens’ committee placed newspaper ads calling for the deportation of “alien” workers. Federal and provincial governments ordered strikers back to work to no avail. Ottawa amended the Immigration Act to deport anyone not born in Canada, including British citizens, accused of sedition.

The citizens’ committee refused to admit — at least publicly — that the strikers were revolting over wages and working conditions. They spread false rumours about how the leaders were illegal aliens, insisting European immigrants were vying to spark socialist revolutions, similar to those that occurred in Russia in 1917 and Germany a year later.

Their propaganda was delivered by the daily newspapers.

“(Immigrants’) ignorance is impenetrable, their customs are repulsive, their civilization is primitive, their characters and morals are justly condemned…. They are surely not the class of people paid immigration agents should seek,” an editorial writer in the Winnipeg Telegram stated.

“It was a strike deliberately engineered by Reds and planned long in advance,” Free Press editor John Wesley Dafoe wrote. He continued propagating the false narrative for at least two years after the strike’s end.

The fake accounts caught the ear of the federal government, fearing the “Red spread” of Russian influences across the country. Sympathy strikes were already springing up, from Vancouver to Amherst, N.S.

Ottawa sent two cabinet ministers to Winnipeg as reinforcements — Arthur Meighen, the acting minister of justice and minister of the interior, and Gideon Robertson, minister of labour.

Strike leaders jailed

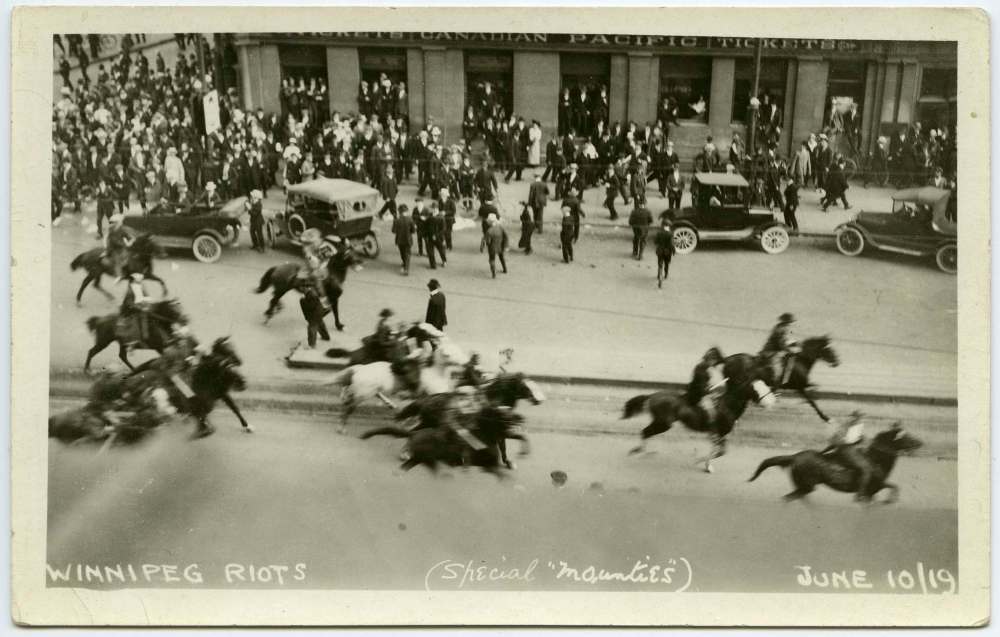

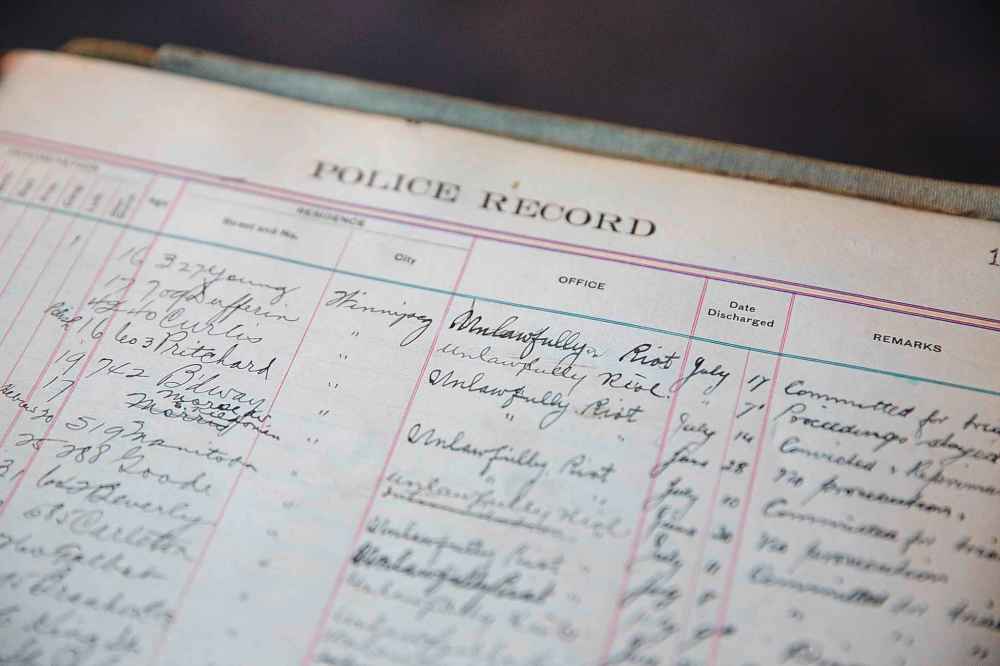

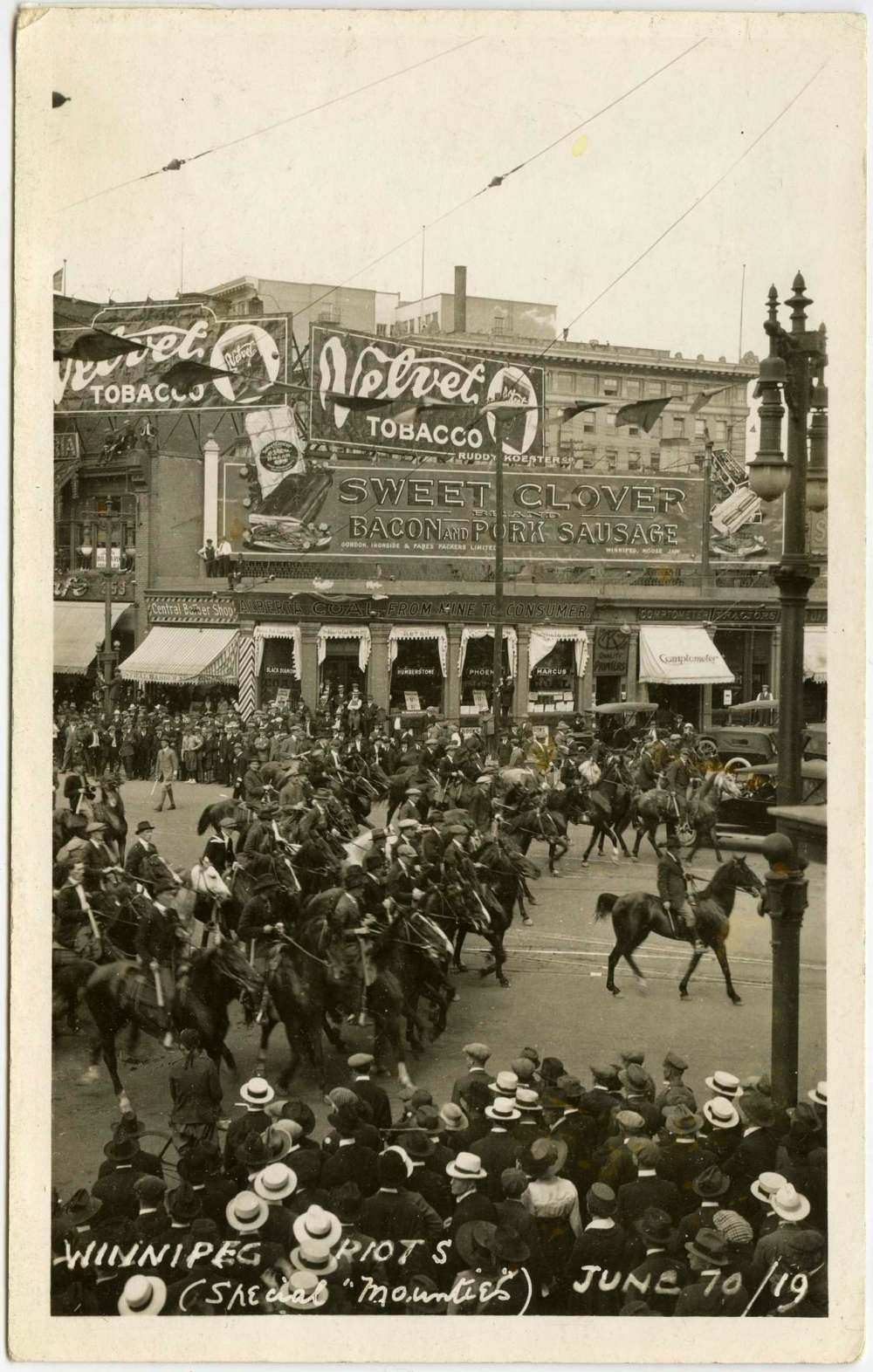

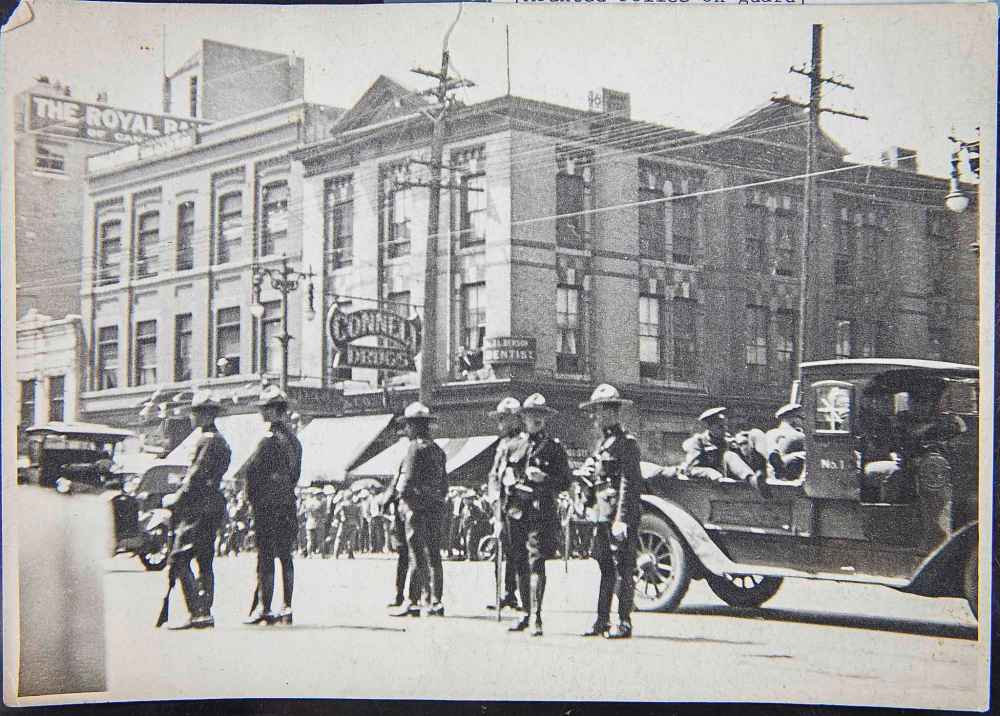

It was the Royal North West Mounted Police raid of strike leaders’ homes overnight June 17 that set the stage for the mayhem to come. Ten leaders were arrested, charged with “seditious conspiracy,” tossed in jail and denied bail, sparking protests across Canada.

A silent parade on June 21 was organized by military veterans who backed the strike.

Thousands of citizens gathered in front of city hall at Main and William to watch the events unfold that day. They were joined by reporters from the New York Times, the Toronto Star, the Manitoba Free Press and others, pencils and cameras at the ready to record details of the increasingly tense situation.

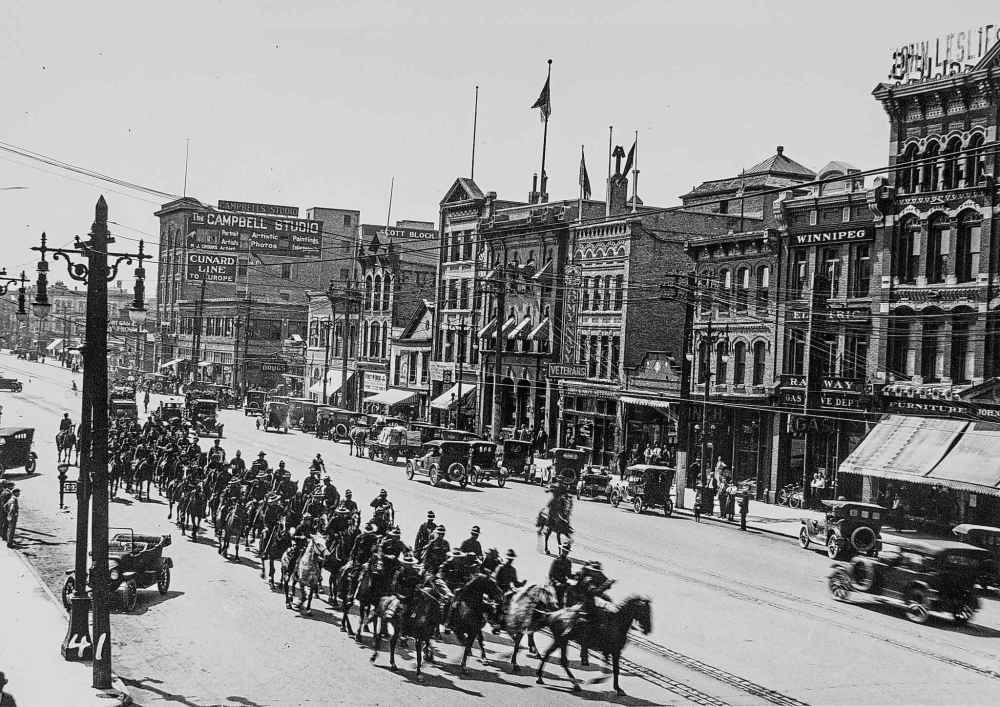

Panicked officials informed mayor Charles Frederick Gray that things were getting out of control. Gray ordered the Royal North West Mounted Police and the military onto the streets; more than 50 police officers on horseback and 36 men in trucks lined up on Main Street near Portage Avenue.

The labour leaders

Helen Armstrong (1875-April 18, 1947): Before the 1919 strike and even before the First World War, Armstrong helped organize women in workplaces such as retail stores and garment factories to fight for their rights. Originally from Toronto, she came to Winnipeg in 1905 with her husband George (also one of the strike leaders who was arrested on June 17, 1919).

Armstrong was anti-war and brought food and clothing to men who were in prison for refusing to serve. She led the Women’s Labour League, which organized a Labour Café downtown that fed thousands of mostly female strikers who couldn’t afford meals without their work paycheques.

Helen Armstrong (1875-April 18, 1947): Before the 1919 strike and even before the First World War, Armstrong helped organize women in workplaces such as retail stores and garment factories to fight for their rights. Originally from Toronto, she came to Winnipeg in 1905 with her husband George (also one of the strike leaders who was arrested on June 17, 1919).

Armstrong was anti-war and brought food and clothing to men who were in prison for refusing to serve. She led the Women’s Labour League, which organized a Labour Café downtown that fed thousands of mostly female strikers who couldn’t afford meals without their work paycheques.

Armstrong headed the Hotel and Household Workers’ Union for a time and was the first woman on the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council. She was nicknamed a “Wild Woman of the West” by newspapers because of her socialist views. She was also arrested many times during the strike for her conduct, which included intimidating “scabs” who replaced striking workers.

She was part of the Central Strike Committee in 1919, the inner circle of about 15 people who plotted strategy. Armstrong pushed for women’s right to vote, but distanced herself from other suffragettes such as Nellie McClung, who opposed unions. She was the subject of a documentary called The Notorious Mrs. Armstrong in 2001.

RB (Bob) Russell (Oct. 31, 1889-Sept. 25, 1964): Russell came to Canada in 1911 from Scotland and worked as a unionized machinist with the Canadian Pacific Railway at the Weston Shops. He refused to utter a racist line in the International Association of Machinists’ oath that asked members to “never nominate for membership… anything but a sober industrious white machinist,” but was allowed to become a member anyway.

In March 1919, Russell attended a major labour conference in Calgary where discussions took place about forming One Big Union, rather than several smaller ones. He was intrigued. Two months later, in May 1919, he became an important player in the Central Strike Committee in Winnipeg.

Russell was among the 10 men arrested for his activism during the strike and found guilty of “seditious conspiracy.” He was sentenced to two years in prison — the most of any strike participant — but served only 11 months due to public outcry. He wound up running for provincial office while incarcerated, but lost to a fellow inmate, George Armstrong.

Russell ran for office a few more times, but never won. He was a prominent member of the Socialist Party of Canada and later led the One Big Union, which evolved into the Canadian Labour Congress in 1956. R.B. Russell Vocational High School on Dufferin Avenue was named in his honour.

Fred Dixon (Jan. 20, 1881-March 18, 1931): A Brit who came to Canada in 1903, Frederick John Dixon wore many hats during his 50 years. He worked as a gardener, construction worker, insurance salesman, journalist, labour activist and MLA.

Dixon was elected to the Manitoba legislature four times, starting in 1914. He once beat out his opponents by collecting more than three times their votes. Dixon pushed for an investigation into corrupt business practices around the construction of the Legislative Building, which eventually pushed premier Rodmond Roblin to resign in 1915. During the 1919 strike, Dixon stepped in to help run the strike bulletin with James Woodsworth after editor William Ivens was arrested.

The bulletin was later renamed the Western Star and Enlightener after the citizens’ committee tried to shut it down. Police put out a warrant for Dixon’s arrest on a charge of libel and, after Ivens was released on bail, he turned himself in.

Dixon fought his charge in court, representing himself in front of a jury during two days of testimony. He won his case, then trotted back across the street, from the law courts to the Legislative Building, to grill the government over who was paying for the strike trials. Dixon never belonged to a union. He was a liberal and fan of reform. Still, he helped the labour movement make major strides in Manitoba. He died of cancer in 1931 and is buried at Brookside Cemetery, but doesn’t have a headstone marking his grave.

Jessie Kirk (1877-Dec. 2, 1965): Jessie Kirk was a schoolteacher and Winnipeg’s first female city councillor. She lived on Wellington Crescent in a chauffeur’s apartment above a detached garage with her husband William (who drove for a living) and their daughter Mary.

The family arrived in Winnipeg from England in 1912. Kirk organized with the Women’s Non-Political Union and lobbied for women’s equality, hospital improvements, food security and adequate housing. She ran unsuccessfully for school trustee in the Winnipeg School Board election in 1919. She nabbed a Ward 2 council seat in Winnipeg the following year. In the 1920s, it was common for politicians to seek office at the municipal and provincial levels, since both were considered part-time jobs that didn’t pay well.

She was selected as a Labour candidate in the 1920 provincial election, but later withdrew her nomination when the party decided to support a full slate of men who were arrested during the strike. Despite her major contributions in Winnipeg’s history, Kirk isn’t well-recognized and doesn’t have a headstone marking her grave in the Brookside Cemetery (although she is buried next to her husband William, who does have a marker).

John Queen (1882-1946): A former barrel-maker who was active in his coopermaker’s union, John Queen grew up in Scotland and arrived in Winnipeg in 1906. He delivered bread, sold insurance and ads for the Western Labour News. But most importantly, Queen became the first socialist mayor of Winnipeg and held a seat in the legislature at the same time.

Queen helped lead the Winnipeg general strike and was one of the 10 men arrested for “seditious conspiracy” due to his involvement. He spent a year in jail and while incarcerated, he was elected as an MLA in 1920. Queen served five terms as MLA and also served as leader of the Independent Labour Party for five years.

Because the MLA position was part-time, he also decided to run for mayor and won that position in 1934. He served two separate terms as mayor. Queen died in 1946 and is buried at Brookside Cemetery. Queen Street (in the King Edward area) is named after him.

Sources: 1919 Winnipeg General Strike Driving & Walking Tour: 100th Anniversary Edition, Magnificent Fight: The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, Brookside Cemetery Tour, The Manitoba Historical Society.

At that moment, things got ugly four blocks north as the streetcar, headed south from city hall, was set upon by fist-shaking strikers blocking the track, shouting epithets at the driver, whom they believed was a citizen’s committee volunteer.

Within minutes, they muscled the 21,300-kilogram vehicle off its tracks, shattered windows and set its seat cushions aflame. The driver and the passengers were able to get out safely.

Police and soldiers made their way from their position near Portage to the pandemonium at William Avenue. Some pro-strike veterans took offence to seeing soldiers in uniform marching with the police, throwing insults first, then rocks and bricks.

Amid the chaos, Gray appeared on the steps of city hall and read the Riot Act, ordering the streets cleared. He was barely audible in the tumult.

The crowds, fuelled by the strike committee’s urgings — “the only thing the workers have to do to win this strike is nothing; just eat, sleep, play, love, laugh and look at the sun” was the message that had been published in the strike bulletin — didn’t budge.

The police, clubs in hand, rode north and then south again in an attempt to disperse the crowds. They did the same thing again with both clubs and pistols in hand. The protesters moved aside to let them pass, but police unexpectedly turned into a crowd at Main and William firing shots, ostensibly to scatter, but some fell wounded, including Steve Szczerbanowicz, who was hit in the legs. He died a few days later from gangrene infection, a result of his infected bullet wounds.

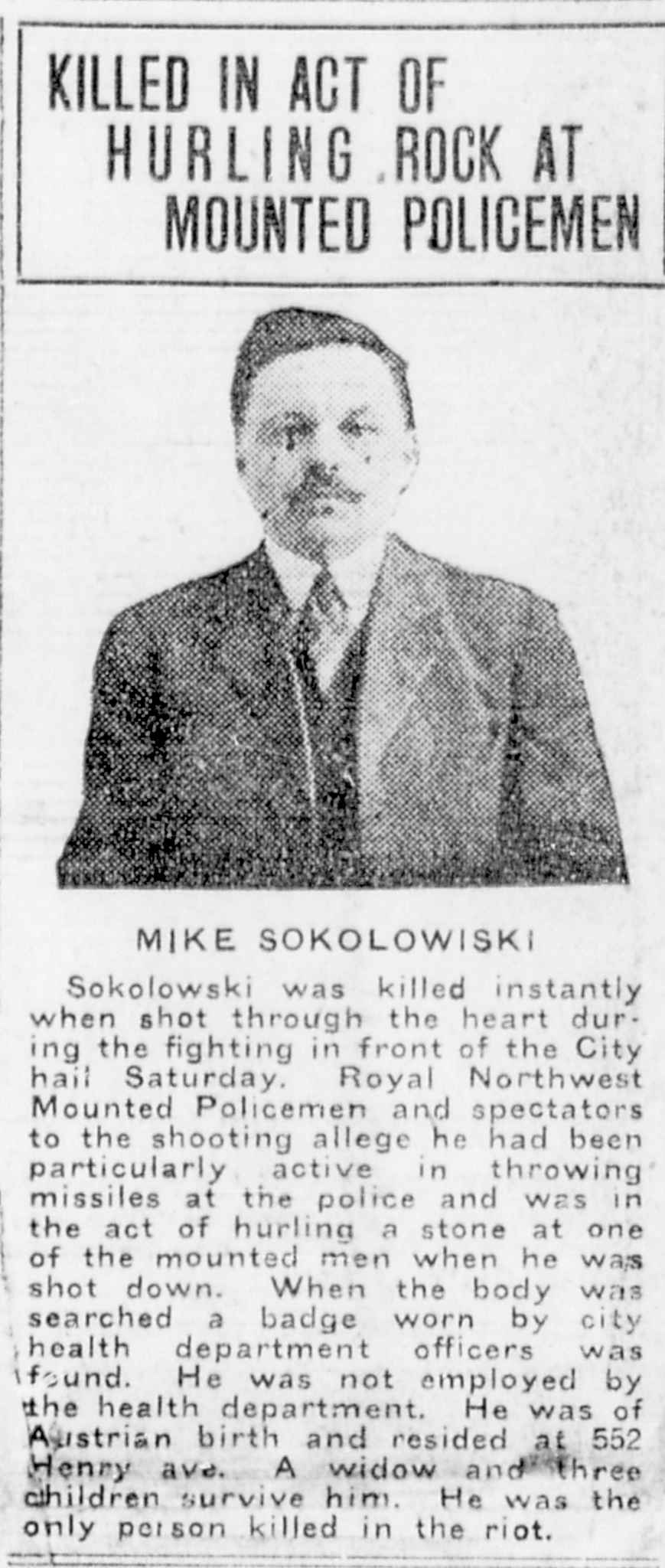

Mike Sokolowski, an immigrant born in western Ukraine, was shot through the heart and died instantly. Local newspapers said Sokolowski, a tinsmith, was throwing bricks at police. Accounts from visiting reporters, however, claimed he was an innocent bystander cut down in the spray of police bullets.

Two weeks earlier, the overwhelming majority of Winnipeg’s police officers were fired after refusing to sign “loyalty pledges” outlawing union organizing among their ranks. The citizens’ committee recruited and paid for “special police” to take their place; most were war veterans as well.

As the violence erupted at Main and William, an estimated 200 of the “specials” charged out of a nearby police station, cornering fleeing men, women and children in alleyways, attacking them with batons and other weapons. Some in the crowd responded with bricks, bottles and their fists.

Fred Livesay, a reporter with The Canadian Press, stumbled upon Sokolowski’s lifeless body in a pool of blood.

“As if reaped by a scythe, the old soldiers lay down, while the rest, men, women and children, streamed like quicksilver into the neighboring courts and alleys,” Livesay wrote later.

“In a moment the square was quiet. Even the troops had passed on, and I stood alone . . . a dead man lay before me.”

Livesay stole Sokolowski’s immigration card to identify him and scooped the rest of the reporters.

At least two others, Robert Johnstone and Jack Barrett, were seriously shot but recovered. Reports had the number of injured at 87, although it’s believed there were many others, primarily immigrants, who wouldn’t have risked deportation by seeking medical help.

It was “Bloody Saturday,” the strike committee’s Western Labor News reported.

In the aftermath of the violence, the military was called in to patrol city streets armed with machine guns.

The strike officially ended five days later, June 26 at 11 a.m. What amounted to about half of Winnipeg’s workforce at the time returned bruised and bloodied to their jobs, at least those who still had them; some strikers found themselves unemployed as angry business owners meted out punishment where they could.

“Those of you who wish to return to your work can do so without fear of molestation, and if you are in the slightest way interfered with or intimidated, notify at once the mayor or chief of police,” Gray proclaimed in the papers days after the violence.

“Any foreigners who make any threats of any kind or in any way intimidate or worry would-be workers in the slightest degree can expect immediate deportation to Russia or wherever they come from.”

It was anything but a harmonious transition. People went back to their lives, but bitterness and resentment continued to simmer just below the surface. Winnipeg would never be the same.

‘They should not be forgotten’

Steps away from where most of the blood was shed, a couple of dozen history buffs shiver in silence on a late-April Saturday morning nearly a century later.

Retired University of Winnipeg history professor Nolan Reilly talks about Bloody Saturday for about 20 minutes.

It’s the last stop on the day’s walking and driving tour of Winnipeg General Strike sites and memorials that he and his wife Sharon decided to offer in the 1980s. Using the steps of the Centennial Concert Hall as his pulpit, the U of W Senior Scholar delivers a speech he’s made myriad times:

“It’s about paying tribute to those people who did all of that (work) for us. And they should not be forgotten and their commitments should not be forgotten,” he tells the group, most of which is made up of union representatives.

“The torch has been passed.”

Victoria Park, now occupied by condominiums and the Mere Hotel on Waterfront Drive between James and Pacific avenues, was ground zero for strikers.

No plaque or any type of obvious marker tells the story of the area’s history, which was nicknamed “Liberty Park.”

Labour leaders shouted from pedestals and their speeches were translated into various European languages for hundreds, at times thousands, listening en masse. The park was where people went to get the news of the day; they couldn’t all fit inside the strike committee’s headquarters at the nearby James Street Labour Temple, now the location of the Manitoba Museum.

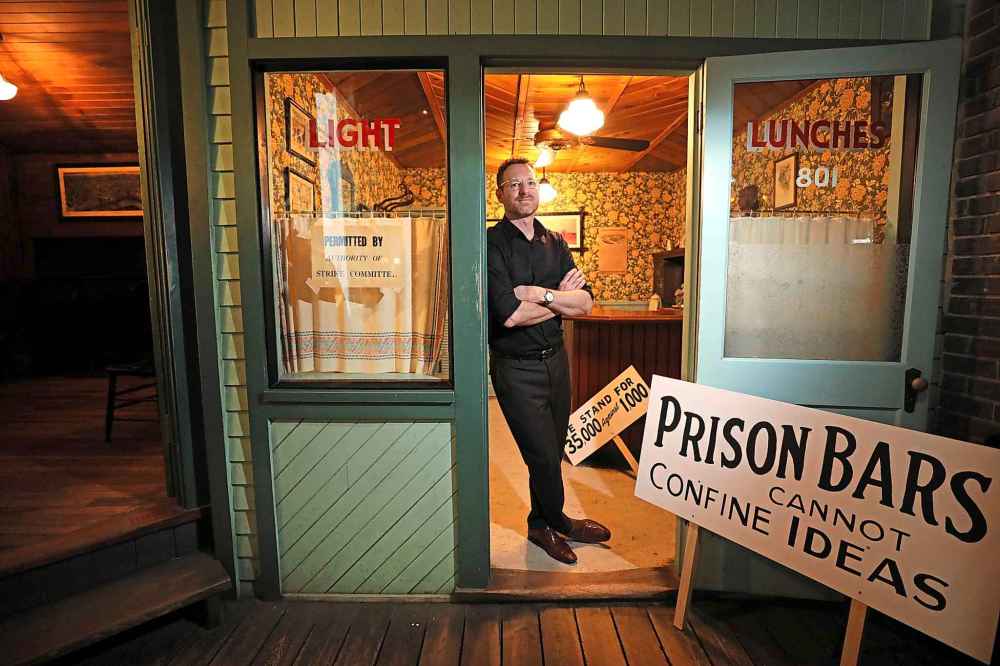

Curator Roland Sawatzky helped organize one of the museum’s latest exhibits, Strike 1919: Divided City, which echoes some modern stressors despite its Old Town setting.

“Labour is not an irrelevant thing. It still makes up a huge part of our lives — how much we get paid, what kind of benefits we have, family work balance,” Sawatzky says.

“All those things are addressed by modern-day labour and have been for a long time. I think sometimes people forget that the standard of living in Canada was developed by people like (the strikers) over decades.”

The battles continue today

The Reillys have worked to ensure students learn about the events in the spring of 1919. Many Winnipeg and Manitoba adults have limited, if any, knowledge of what took place beyond the iconic image of the besieged streetcar.

Beginning in 2010, Sharon Reilly prepared curriculum kits for Manitoba Education and Training. The former Manitoba Museum and Canadian Museum for Human Rights curator has a wide-lens view of the subject, which most students are exposed to in Grade 6 social studies.

The couple has collected strike memorabilia over the years, including pins, posters, a billy club and a ballot box.

She’s aware of how many intersectional battles existed in the labour movement then. And now.

“Some of the things that came out of the strike, the movements that people put their energy into following the fight for a social-welfare system, for universal health care, for minimum wage, for compulsory education to (age) 16…. It’s easy to forget people didn’t have any of those social safety networks at that time,” she says.

“And there are many more battles, like affordable wages, equal opportunity in the workplace, where women get as far as men get. We still have to keep working to make that happen. And then when we push beyond women… look at Indigenous peoples’ struggles, persons of colour, LGBTQ people. All kinds of folks have to struggle even harder.”

Nolan Reilly chimes in, holding the billy club for emphasis.

“What they were doing in 1919, they were drawing attention to those (injustices) and they were searching, and maybe that’s the most important lesson,” he says.

“You don’t stop searching for those alternatives that will improve and make things better.”

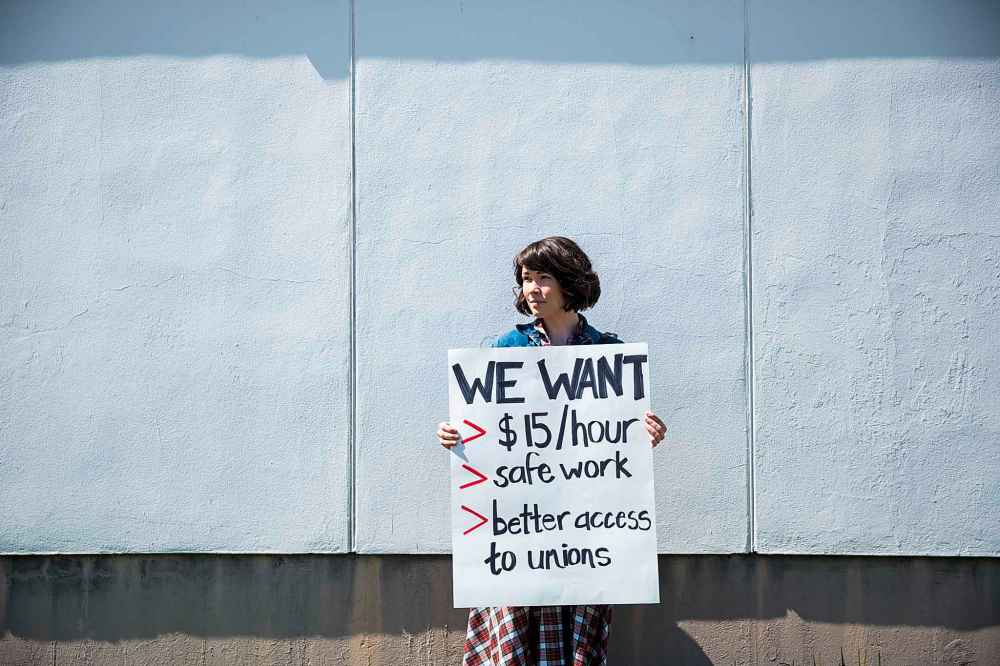

What was then is now, too. Anti-poverty activists are currently fighting to raise Manitoba’s $11.65 per hour minimum wage to $15.

Emily Leedham, an organizer with the Fight for $15 and Fairness Manitoba campaign, is advocating for stable working conditions as Western societies shift to a more freelance, gig economy.

Officially kicked off last September, Fight for $15 is a long-term campaign with a big-picture vision, she says, with focus on workers who are fed up with the status quo.

“I have worked minimum-wage jobs since I was 15 years old and I’m almost 30 now and still working a minimum wage job,” Leedham says.

The University of Calgary grad has a women’s studies degree. After applying for and losing out on a job she was qualified for at an agency where she volunteered, Leedham learned she’s far from alone on her uphill climb in search of decent work.

More than 300 people applied for the same job she did, management told her.

“This isn’t a situation where if I work hard enough, if I go through all the steps, I will finally get a good job,” she says. “So many people are in this position and it’s a problem with the wages people pay.

“Even if you get a job that might be considered a good job, (bosses) are still trying to drive down wages. They’re still trying to squeeze you in different ways, right? So no matter what job you’re in, being involved in a union and labour organizing is important.”

She’ll get no argument from Paul Moist, president emeritus of the Canadian Union of Public Employees.

After serving in a multitude of union roles, he retired in 2015 and began researching people who were connected with the strike who are buried at Brookside Cemetery.

Moist has organized tours examining the personal histories of 14 key contributors buried there in hopes echoes of the past will inspire future generations to keep fighting for labour. Recent Statistics Canada data shows about 31 per cent of Canada’s workforce was unionized in 2015 and the rate is trending downward.

The graves include one for arrested and jailed strike leader John Queen, who went on to serve in the legislature and as Winnipeg’s mayor. Mike Sokolowski’s headstone is one of the newer markers, installed in 2003 after a fundraising campaign spearheaded by Winnipeg playwright Danny Schur to remember the fallen labour soldier.

The missing headstones are, perhaps, even more powerful. Three of the graves — those of Frederick Dixon (a former MLA), Jessie Kirk (Winnipeg’s first female city councillor) and Matilda Russell (a women’s rights activist) — aren’t marked, something Moist hopes to rectify.

There is a lot of interest in the strike’s history in its centennial year, he says.

Lunch-hour information sessions offered at the Millennium Library recently were well-attended. The Mayworks Festival of Labour and the Arts has more than two dozen related events running until June.

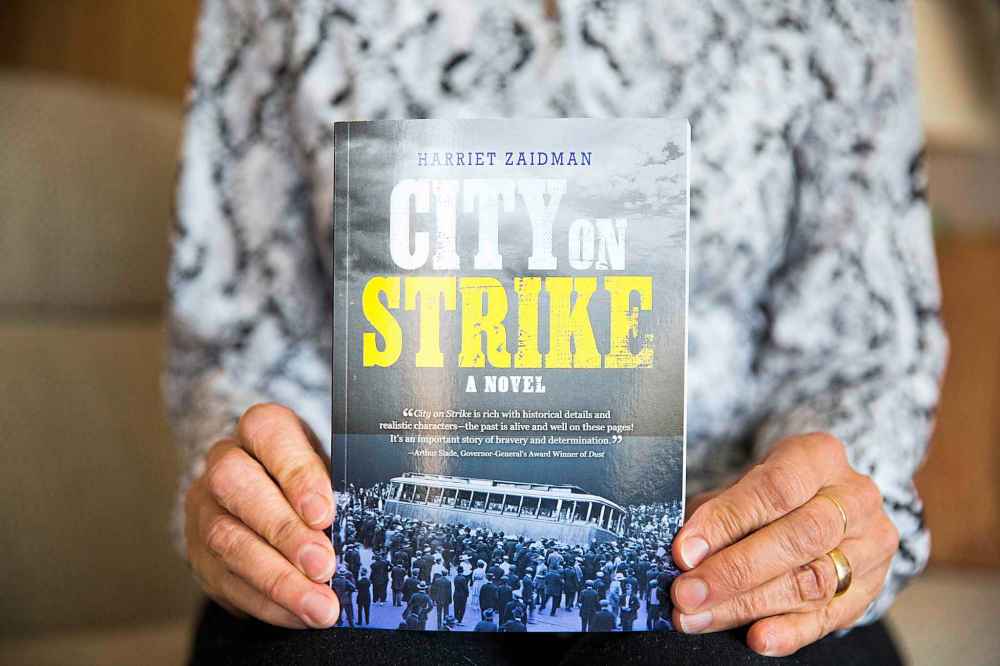

Several books marking the strike’s centenary have been or are about to be printed, including Harriet Zaidman’s fictionalized young adult book City on Strike.

Zaidman, a retired Winnipeg teacher and librarian, mined her own family’s history, among several other sources, to construct the story. One of her grandmothers was a garment worker and one grandfather managed to flee to safety on Bloody Saturday.

While she didn’t want to write a play-by-play of her own family’s history to protect their privacy, Zaidman sees the value in retelling the strikers’ stories, especially to children.

“When I talk to kids, I talk to them directly about racism and being critical thinkers,” she says.

Most of the students don’t quite understand what she means by racism, Zaidman says, because they’re surrounded by multiculturalism in their schools. They haven’t been witness to Winnipeg’s past and present prejudices.

Many kids are new to Canada and know little about the city’s history. Stories — both fiction and non-fiction — can help them understand, she says.

Easier said than done; much has changed in 100 years. Sadly, much has not.

Winnipeg was divided by race, class, gender and geography in 1919. It still is in 2019.

Labour activist Dixon once called the strikers’ mission a “magnificent fight.” Those in the local union movement say it isn’t over.

“Labour was not prepared for the long and bitter struggle, which was forced upon her by the bosses six weeks ago,” Dixon wrote in the Western Labor News, as the strike came to its end in 1919.

“But in spite of her unpreparedness labour made a magnificent fight. Now get ready for the next fight,” he urged.

“Never say die. Carry on.”

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @_jessbu

History

Updated on Saturday, May 11, 2019 3:09 PM CDT: Deleted incorrect information pertaining to R.B. Russell

Updated on Saturday, May 11, 2019 4:11 PM CDT: Made correction to R.B. Russell fact box

Updated on Monday, May 13, 2019 3:37 PM CDT: Corrects date when walking tour started