Every picture tells a story Seth fanning the flames is one reason why graphic novels have become red-hot

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/04/2019 (2424 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

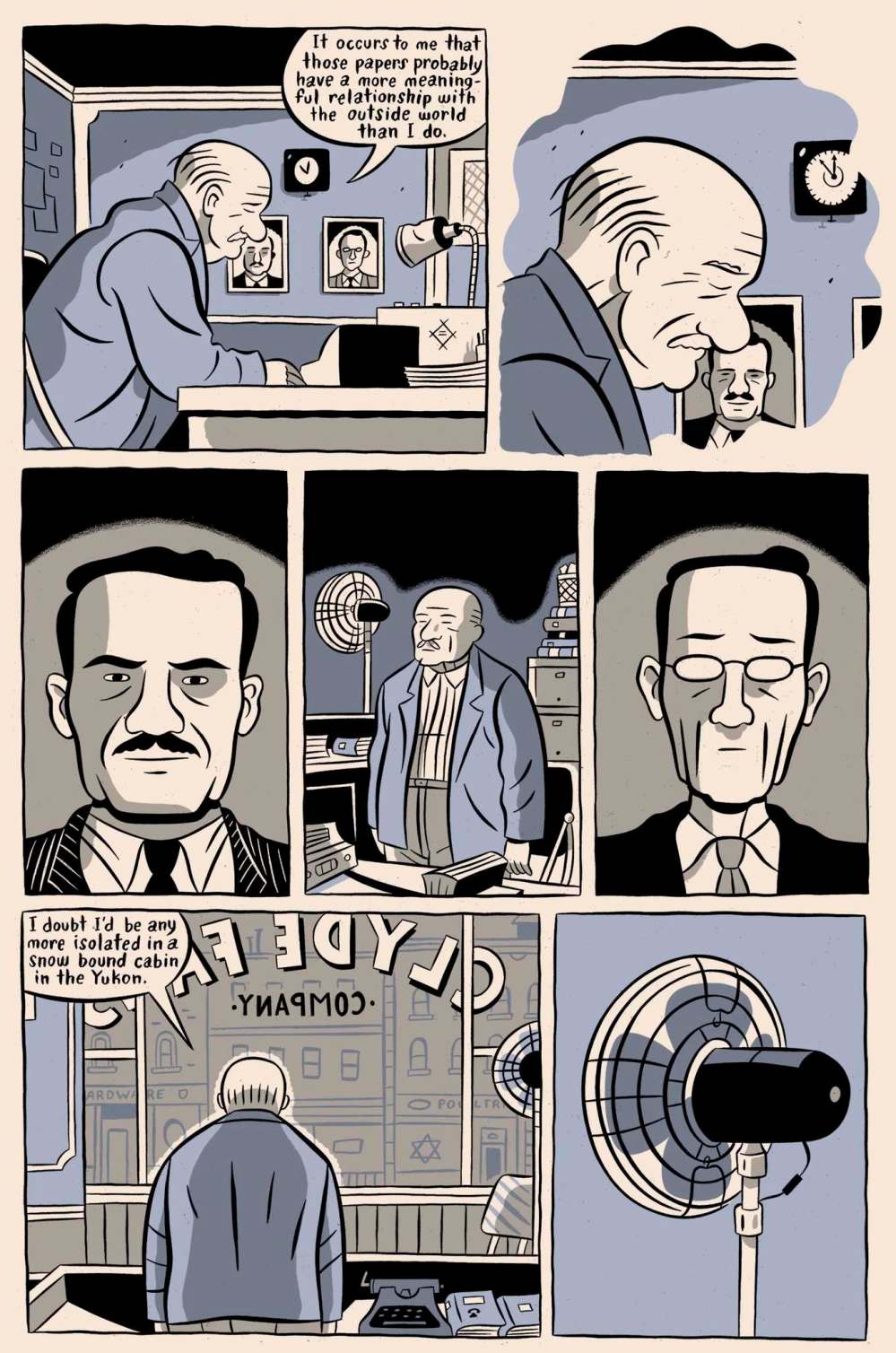

Chronicling the downfall of a company that produces oscillating fans might not sound like the stuff of gripping fiction, but in the hands of an accomplished artist like Seth it becomes a sprawling yet intimate work of melancholy beauty.

Preview

An evening with Seth

In conversation with Candida Rifkind

McNally Robinson Booksellers, Grant Park

Tuesday, 7 p.m.

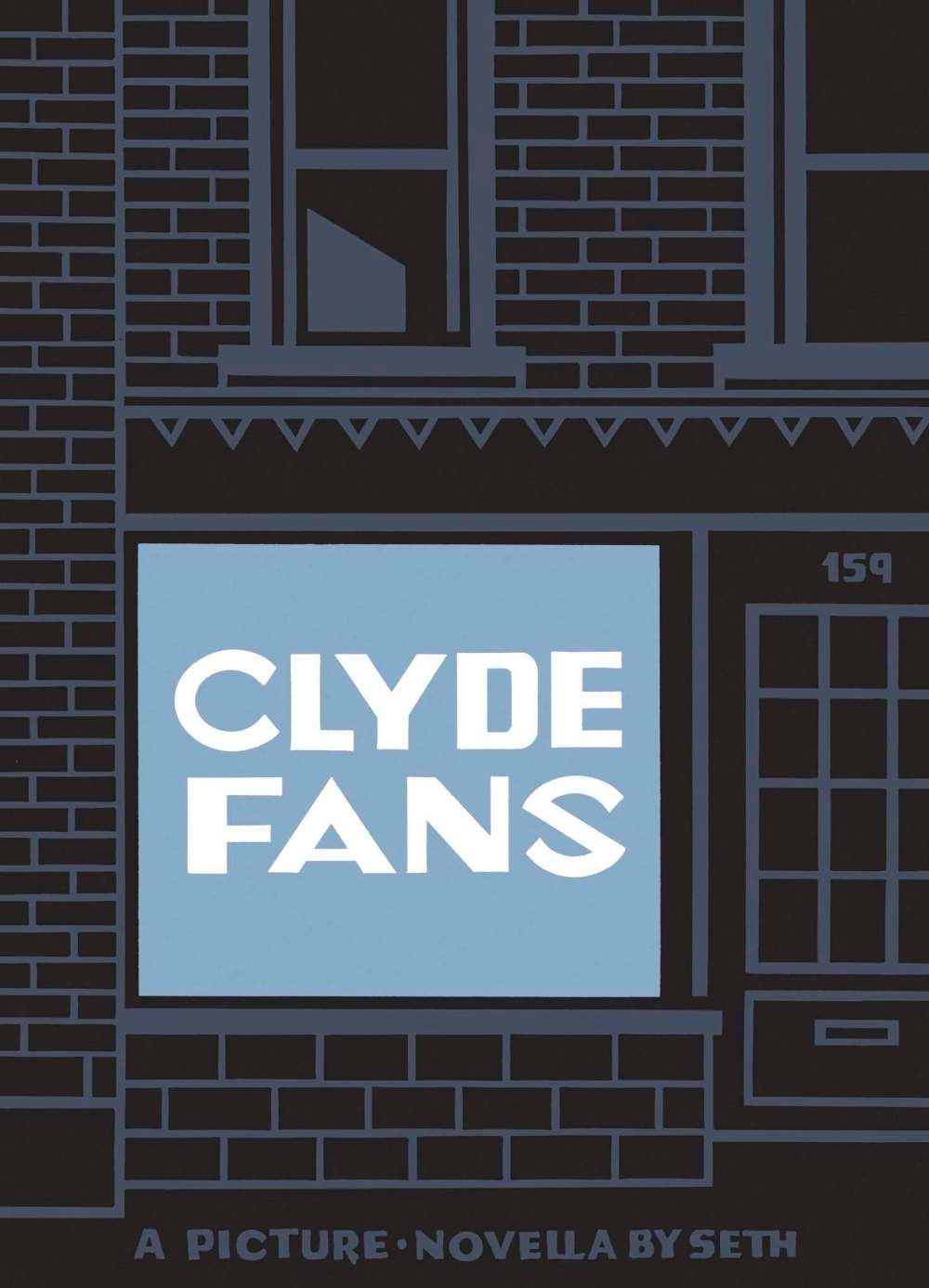

Clyde Fans, published Tuesday by Montreal publisher Drawn & Quarterly, collects Seth’s story of Abe and Simon Matchcard in an impressive, beautifully constructed volume that is certain to be a benchmark for much of what will follow in graphic fiction — from an artist who has helped define the graphic novel genre (although he prefers to call them “picture novels”).

The Matchcards’ story has been published in serial format over the last two decades — first appearing in Seth’s Palookaville comic book series and then compiled into two separate Clyde Fans volumes. And while the story was presented over the course of years before the new definitive collected works, for Seth, 56, the core story was always there.

“The biggest surprise was that the book was basically written in note form, 20 years ago, and that I followed those notes pretty much exactly,” he says from his home in Guelph, Ont., prior to tonight’s launch of Clyde Fans at McNally Robinson’s Grant Park location, where he’ll be joined in conversation with University of Winnipeg professor Candida Rifkind.

“There’d be new notes over the years; I’d write notes to myself like ‘don’t forget to include such and such,’ or ‘don’t forget to do this in Part 4.’ I kept folders of these, and I’d read them as I went along to remind myself. But in my head I had a pretty clear map of scene to scene from the start.”

This attention to detail has long been one of the hallmarks of Seth’s visual work.

In the late 1990s his debut graphic novel, It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken, caught the attention of many in the cartooning world, and he’s been producing a steady amount of high-quality, critically acclaimed work ever since, including books such as 2009’s George Sprott and 2005’s Wimbledon Green.

In addition to his graphic novels, Seth has also worked on jackets of other writers’ books, albums and film covers and more, and in 2014 was the subject of a National Film Board of Canada documentary called Seth’s Dominion.

Dominion is the name of the fictional Ontario town in which most of Seth’s stories take place. His world-building doesn’t just take place on the page; he has also created his fictional town in model format that features dozens of buildings rendered in fine detail and that allows Seth’s imagination to take him in new directions within the town.

“There’s no end to what you can make up about a fairly large city,” he says. “I just did a long script in one of my notebooks that covered about 30 pages. I thought, if you walk between the train station and one of the big hotels, what do you encounter in between?

“So I wrote this thing, made up all this history, and at the end of that you have a big historical section of the city’s story that you didn’t have before. So now you have 20 new ideas, and those will later combine with other things you’re writing.”

For Seth, constantly sketching and writing in notebooks is a way to process all manner of storylines and ideas — whether they ever end up on the finished page or are simply secondary detail.

“Over the last 10 years, Dominion has grown in complexity. And of course there are a ton of characters — different mayors, historical figures — and none of them are in any of my finished work. They may never be, except perhaps in the background.

“When I do a story that takes place in Dominion — and I will again in the next few years — I’ll know where I am, the history of that neighbourhood. It makes for a very rich imaginary world in my head. In some ways that’s maybe the most important part of anything I work on.”

The story of Clyde Fans spans the course of four decades between 1957 and 1997, as a combination of personal issues and a declining commercial market for oscillating fans sends the titular company spiralling downward.

The five-part novel jumps back and forth in time and from brother to brother as Abe tries to keep the company afloat amid his dissolving marriage while Simon’s psychological issues assures his failure as a travelling salesman for the company, returning instead to become reclusive while tending to brothers’ aged mother.

Together with Drawn & Quarterly, Seth worked fastidiously on compiling the story into one volume, and was involved in every aspect of the book’s design.

“I’ve had a 30-year relationship with Drawn & Quarterly. The company has changed dramatically since I started; initially it was just the publisher, Chris Oliveros, in the corner of his bedroom,” Seth recalls.

“Now it’s a real publishing house… but the amazing thing is that somehow, over all this time and through all these changes, the company has as much integrity, and has shown as much personal care towards what I’m doing. I always feel like it was a miracle that I got involved with them.”

When Seth started out as a cartoonist, the opportunity to collect his Clyde Fans story into one sprawling volume would never have existed. But the surprising rise of graphic fiction (and non-fiction) has provided the chance to earn new fans and regular readers.

“Around the late 1990s it looked like comics were dying entirely. But now cartoonists of my generation are surprisingly well-placed to take advantage of this change in that we have a large body of work behind us.”

“Around the late 1990s it looked like comics were dying entirely,” he says. “But now cartoonists of my generation are surprisingly well-placed to take advantage of this change in that we have a large body of work behind us.”

And while Seth can’t definitively explain the rise in popularity of graphic novels, he has a theory or two.

“One of the reasons I think the graphic novel has become successful maybe isn’t the most flattering. I think in this era of digital communication, people are used to looking at combinations of words and pictures, and it’s an easy form.”

Which is not to say graphic novels are simple things. For the first time, last year’s Booker Prize short list included a graphic novel — Nick Drnaso’s widely lauded Sabrina.

And for artists such as Seth, the combination of words and images is a medium through which great emotion and profound ideas can be communicated.

As for building the story through images versus words, in Seth’s mind there’s no question which comes first.

“It’s like writing a song,” he explains. “Nothing really starts to come to life until you write the music. For me, the drawing is the music.”

books@freepress.mb.ca