Ontario ruling a lesson for all governments

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/09/2018 (2649 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

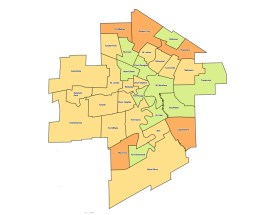

Ontario Premier Doug Ford hit the roof yesterday after the Ontario Superior Court shot down his attempt to cut the size of Toronto city council.

The provincial government can set the size of Toronto’s council, Judge Edward Belobaba found, but it cannot do it abruptly, arbitrarily, without consultation or in the middle of an election campaign. Just watch me, Mr. Ford, in effect, replied. Mr. Ford is recalling his legislature to re-enact its abrupt, arbitrary shrinking of the council. He will use the notwithstanding clause, the nuclear option in the constitutional Charter of Rights, in order to insulate his action from court challenge.

Mr. Ford took power on June 29 and soon announced he was cutting the council. He swiftly put Bill 5 through the legislature, cutting the council to 25 seats from 47, though candidates were already nominated and campaigning for the scheduled Oct. 22 election.

Judge Belobaba was clearly troubled by the slender underpinnings of the bill. “There is no evidence that any other options or approaches were considered or that any consultation ever took place,” he wrote. “It appears that Bill 5 was hurriedly enacted to take effect in the middle of the city’s election without much thought at all, more out of pique than principle.”

The immediate result may be a continuing struggle in court over the date and rules for this year’s scheduled Toronto civic election. Someone will have to figure out — with adequate consultation and consideration of options — how many councillors Torontonians will elect and when to elect them.

The wider effect should be to warn all Canadian governments against hasty action without adequate consultation. The federal government, similarly, was shot down on Aug. 30 by the Federal Court of Appeal for approving the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project without adequately consulting the Indigenous communities concerned and without adequately studying the project’s effects on killer whales.

What is the notwithstanding clause?

The Ontario government’s unprecedented use of the notwithstanding clause in order to proceed with plans to cut the size of Toronto’s city council has raised some questions about this rarely used section of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Ontario government’s unprecedented use of the notwithstanding clause in order to proceed with plans to cut the size of Toronto’s city council has raised some questions about this rarely used section of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

WHAT IS IT?

The notwithstanding clause — or Section 33 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms — gives provincial legislatures or Parliament the ability, through the passage of a law, to override certain portions of the charter for a five-year term.

ITS ORIGINS

The notwithstanding clause has its roots in the 1960 Bill of Rights, largely seen as the precursor to the charter. The clause in its current form came about as a tool to bring provinces on side with then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s signature piece of legislation. With charter negotiations ramping up in the early 1980s, Trudeau didn’t see the need for the clause, but provinces such as Alberta and Saskatchewan wanted an out should they disagree with a decision of the courts. In the end, Trudeau reluctantly agreed.

Constitutional lawyer Asher Honickman said the clause, which only applies to sections 2, 7 and 15 of the charter, was part of the grand compromise that got the charter enacted in 1982.

ITS STRUCTURE

The clause only applies to certain sections of the charter. For instance, it can’t be used against provisions that protect the democratic process — that would create a pathway to dictatorship. The clause also can’t be used for more than five years at a time. This ensures that the public has the chance to challenge a government’s decision to use the clause in a general election before it can be renewed.

ITS USE

The notwithstanding clause usually comes up whenever there is a controversial court ruling. For instance, former prime minister Stephen Harper’s Conservatives were asked about, but refused to use, the clause on a court decision involving assisted dying. While often debated, its use is much rarer. Quebec, as the only provincial government to oppose the charter, passed legislation in 1982 that invoked the clause in every new law, but that stopped in 1985. In 1986, Saskatchewan used the clause to protect back-to-work legislation and Quebec used it again in 1988 to protect residents and businesses using French-only signs. Alberta tried to use the clause in a 2000 bill limiting marriage to a man and a woman, but that failed because marriage was ruled a federal jurisdiction.

—The Canadian Press

Ottawa was confident in its constitutional power to regulate the pipeline project — just as confident as the Ontario government was in its power to regulate the size of Toronto’s city council. The two cases taken together show that it’s not enough for a government to show it has the power to act: it must also show that it had good reasons for its action, that it studied the consequences and that it consulted the people affected.

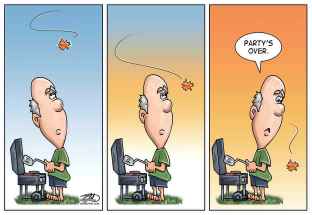

Canadians should not conclude that you cannot reform a city government in Canada anymore. Neither should they conclude that you cannot build a pipeline in Canada anymore. A better conclusion is that governments have to learn to work within the law and show decent respect for the views of the people affected by their actions. Governing in this way may seem time-consuming, but consulting people should not be seen as a waste of time. What really wastes time is acting hastily, getting shot down in court and then starting all over again.

Mr. Ford’s theory is that he won the election and therefore he need not comply with an adverse court ruling. But the law, slowly developed over many centuries, is one of the protections for the freedoms of Canadians. One electoral success should not weaponize a premier’s impatience with a city council or a prime minister’s impatience with pipeline protesters. The solution is to govern more wisely, not to swing the constitutional sledgehammer.