Truth, justice and the Dangerfield way Unsealed documents in Appeal Court review of 31-year-old murder conviction reveal troubling deal adding to Manitoba star prosecutor's dubious record of overturned verdicts

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/05/2018 (2754 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Reduce the Robert Nieman murder case to its essential elements, and this is what you have.

An unsympathetic victim who met his end at the hands of a group of career criminals who, when the going got tough, turned on each other. Police and prosecutors determined to take down as many of the bad men as possible, by whatever means necessary. And a justice system that was, in the end, betrayed and deceived by the very people charged with ensuring its integrity.

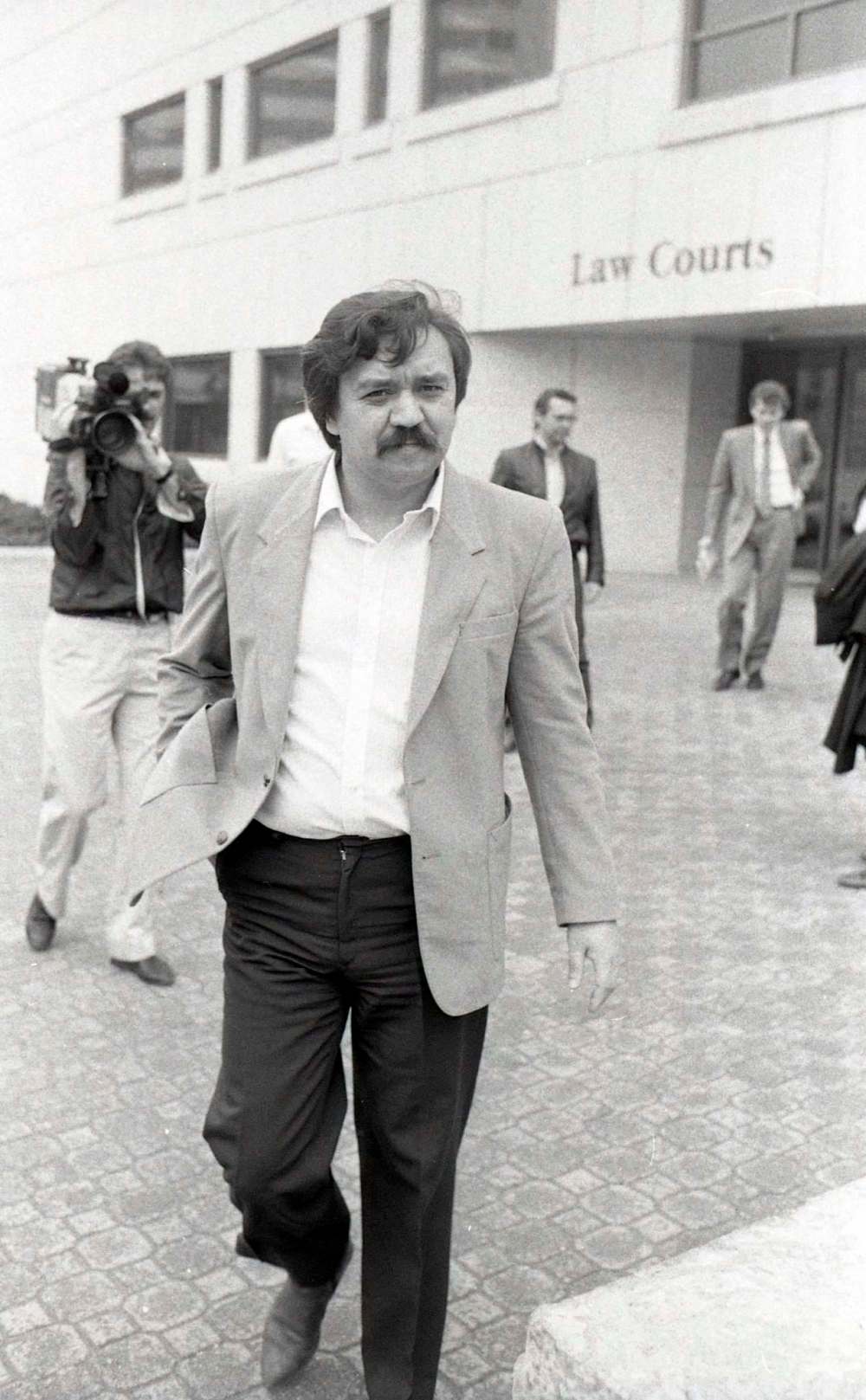

The definitive, lamentable truth of the Nieman murder case became part of the public record Monday morning, when the Manitoba Court of Appeal heard final arguments in the extraordinary review of the conviction of Frank Ostrowski, the man police and prosecutors held responsible for ordering Nieman’s contract assassination in 1986.

Ostrowski had always pleaded his innocence, and claimed he was set up by criminal colleagues who were seeking deals on other charges. He won the opportunity to plead his case before the appellate court in 2014, after the federal Justice Department concluded “there is a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice likely occurred,” largely because “relevant and reliable information was not disclosed” to Ostrowski or his lawyers during his original trial.

Based on those findings, and the fact it would be very difficult to retry Ostrowski more than 30 years after the original trial, Manitoba Justice indicated Monday morning it is prepared to expunge Ostrowski’s conviction and enter a stay of proceedings. Ostrowski’s legal team, which includes Toronto lawyer James Lockyer and Winnipeg attorney Alan Libman, are seeking an acquittal.

Most of the new evidence, which has now been obtained by the Free Press, has been kept from the public record because of an unusual publication ban ordered by the Appeal Court when hearings began last year. As final arguments began this week, that publication ban was lifted, allowing the full and awful truth of the Ostrowski case to come into view.

Take away the personalities and the broad spectrum of dirty tricks and double-crosses, and the new evidence tells us this: the Nieman murder case is a prime example of how certain prosecutors and police officers believe it is acceptable to use whatever means necessary to put bad men in prison. Even accusing and convicting them of something they didn’t do.

•••

There is only a handful of facts everyone can agree upon.

Just after midnight on Sept. 25, 1986, Nieman was shot three times in the head, execution-style. He did not die immediately; it took nearly a month before he succumbed to his injuries.

In the intervening weeks, police built a case against four men, all of them hardened criminals: Robert Dunkley, the so-called trigger man; Jose Luis Correia, an accomplice to the murder; Jim Luzny, who had helped orchestrate the hit; and Ostrowski, who police argued ordered the killing to punish Nieman for ratting him out, leading cops to a stash of cocaine and drug money hidden in a safe under a hot tub in Ostrowski’s house.

The case would ultimately hinge on the testimony of a fifth man, Matthew Lovelace, another experienced criminal. As was the case with Ostrowski, prior to Nieman’s murder, Lovelace was arrested for cocaine trafficking. It was following this brush with the law that he would, according to justice officials, become the key informant who described Ostrowski’s plans to have Nieman murdered.

Lovelace would testify at trial Ostrowski told him he had put a hit out on Nieman for being a rat and had provided Luzny with a gun he would pass on to Dunkley and Correia to carry out the execution. Lovelace testified in the hours just before the shooting, he called police to warn them Ostrowski had arranged a hit on Nieman.

More important, when he was on the stand, Lovelace repeatedly denied he was getting anything in exchange for his testimony. In particular, he denied any deal had been reached to reduce or eliminate his drug-trafficking charges.

Dunkley and Correia were convicted of murder, along with Ostrowski. Luzny was acquitted. Lovelace, meanwhile, appeared to have won the justice-system lottery.

In November 1988, Lovelace’s drug-trafficking charges finally made their way to trial. The federal prosecutor handling the case declined to call any evidence and entered an acquittal. The court accepted the prosecutor’s motion and adjourned. In all, it took a matter of minutes to make Lovelace’s legal troubles go away.

At the time, no one from the justice system would explain why the drug case against Lovelace had fallen apart. Final decisions on abandoning these cases rarely result in explanatory memos or other correspondence. Prosecutors generally do not discuss their reasons for the decisions they make. And yet, Ostrowski and his legal team always believed there was more to the Lovelace acquittal.

And there was.

Among the recently uncovered documents are two key pieces of evidence that show not only was Lovelace lying to the jury when he testified, but justice officials were aware he was lying and did nothing.

The first smoking gun is a series of documents offering solid proof federal prosecutors collaborated with Winnipeg police, Manitoba Justice and Lovelace’s attorney, Hymie Weinstein, to construct a secret deal to make the drug-trafficking charges disappear.

This deal was first revealed publicly in 2014 when Ostrowski applied for and won bail pending the Court of Appeal hearing. Weinstein said at the time he had asked for a quid pro quo for his client — a walk on the trafficking charges in exchange for testimony against Ostrowski — but did not tell his client about the deal so he wouldn’t “taint” his client during the trial. He did not reveal the existence of the deal for two years, until after Ostrowski had exhausted his avenues of appeal.

Additional documentation uncovered by Innocence Canada (formerly known as the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted), which is representing Ostrowski, confirmed what Lockyer and Libman argued in court was a complex and deliberate effort by justice officials at both the federal and provincial levels to keep the deal secret.

The key piece of new evidence is a December 1986 memo written by then-federal prosecutor Judith Webster, in which she confirms the preliminary details of a deal with Lovelace to have him walk on the drug charges if he comes through with testimony against Ostrowski. The memo notes the deal should come to fruition if Lovelace “delivers the goodies.” She also confirms in the handwritten note Weinstein had asked that no written account of the deal be produced, something that was later approved by her superior in federal justice, Peter Kremer. Other correspondence strongly suggested provincial Crown attorneys would have to sign off on the deal.

At trial, Lovelace repeatedly denied receiving any consideration for his testimony. His pleadings were aided to a significant degree by provincial Crown prosecutor George Dangerfield, who took the time to explain to the court his office was convinced Lovelace was providing testimony as part of an effort to turn his life around and his concern about how Nieman was treated by Ostrowski. “Those charges that (Lovelace) faced then, he faces now,” Dangerfield told the jury. “He never made a deal to give them Frank Ostrowski…. Here is Lovelace, a young man with no prospects in life. The only hope he has is that he’s going to serve a term of imprisonment.”

According to Weinstein and others, the deal to stay his drug charges was not revealed to his client until just before his trial, which just happened to be several months after Ostrowski’s appeals were denied. Although just about everyone in the justice system has decried this strategy as morally and unethically unacceptable, it was par for the course back in the day.

However, this was not the only smoking gun that reveals the extent of the Crown’s capacity to play dirty.

The Lovelace deal documentation becomes particularly damning when it is combined with something known in the case as the Jacobson report. Written by a former Winnipeg Police Service Sgt. N. Jacobson, the report summarizes the call Lovelace made to police to tip them off about the Nieman murder. Except the report, backed up by Jacobson’s testimony before the Court of Appeal, confirmed Lovelace was not talking about Nieman when he called. He was trying to tip the cops off about another man he thought Ostrowski was going to have killed.

Jacobson’s notes show Lovelace said on that call “Frank (Ostrowski) has a contract out on my friend, I am not taking any chance.” Lovelace later goes on to describe that friend as “the carpenter.” The Innocence Canada investigation confirmed the friend in question was Dominic Diubaldo, a carpenter who had built the secret safe for Ostrowski that contained drugs and money.

The theory Diubaldo may have been the “friend” referred to by Nieman makes sense given an informant did, in fact, provide police with information about the secret safe, and that only Diubaldo and Lovelace knew of the safe’s existence.

However, when Lovelace testified, he indicated the “friend” he referred to in that call was Nieman. Someone, at some point in the leadup to the trial, convinced Lovelace to lie about his call to police prior to the Nieman murder. The Jacobson report was never included in the Manitoba Justice file on the Ostrowski prosecution, and was not disclosed to his lawyer. To this day, Manitoba Justice officially denies any of its people had knowledge of the deal with federal prosecutors.

Add them together and you have what Lockyer and Innocence Canada have described as a deliberate strategy to not only keep Lovelace’s deal secret, but also coerce him into lying to the jury. That seems, at first blush, to be a rather tall tale. However, it’s not the first time one of Dangerfield’s star witnesses lied to a jury.

•••

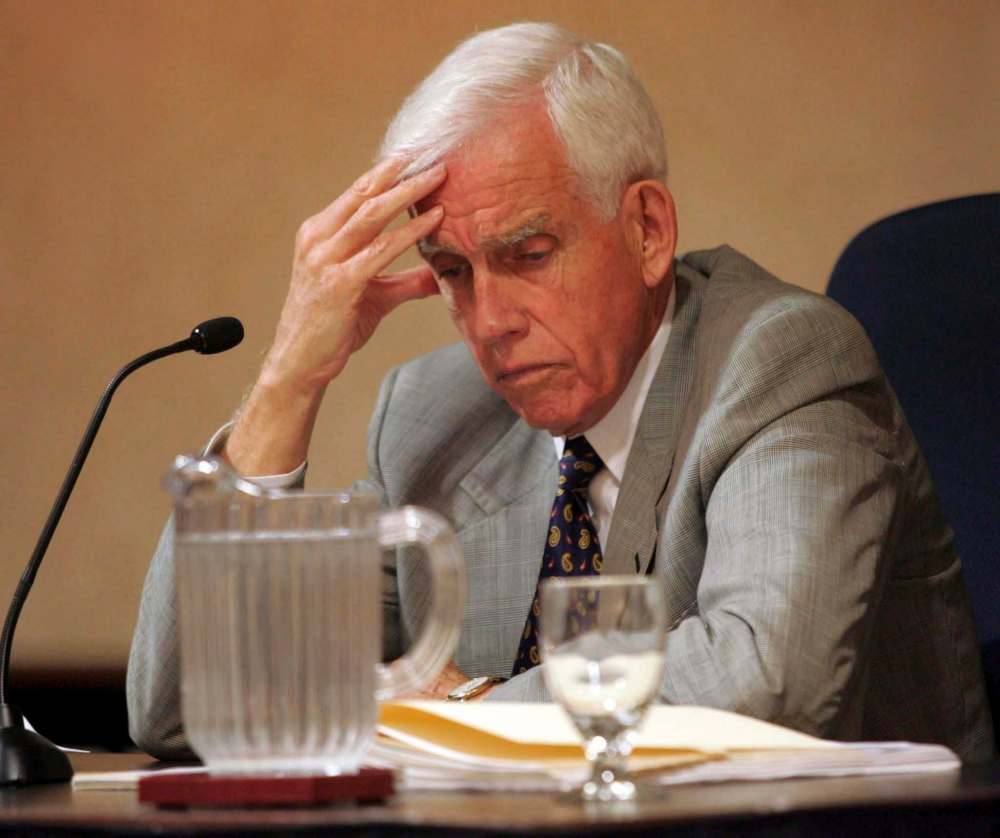

Frank Ostrowski may be the man fighting for his life before the Manitoba Court of Appeal, but the extraordinary hearings before the province’s appellate court are focused just as much on prosecutor George Dangerfield.

If Ostrowski is freed from his original conviction — and given Manitoba Justice has already offered to expunge the conviction and enter a stay of proceedings — it would be the fourth wrongful conviction of Dangerfield’s career. One of the most storied prosecutors in the province’s history, Dangerfield was also the lead prosecutor for now-vacated convictions of Thomas Sophonow, James Driskell and Kyle Unger. In all of those cases, it was revealed Dangerfield resorted to questionable tactics to secure convictions.

Driskell is the most relevant case for Ostrowski’s purposes. A 2003 investigation by the Free Press revealed the star witness used to convict Driskell, Ray Zanidean, was paid tens of thousands of dollars and given a full witness relocation deal in exchange for his testimony. He was also freed from having to face arson charges in Saskatchewan.

At trial, Dangerfield led Zanidean through testimony in which he denied receiving any consideration. When the full extent of the Crown’s payments were made public, Dangerfield claimed he had no personal knowledge of what his witness was being paid or provided with during the trial.

Those claims were deconstructed at the 2006 judicial inquiry into the Driskell wrongful conviction. Justice Patrick LeSage, the inquiry’s chief commissioner, determined in his final report Dangerfield did, in fact, know enough to be aware his witness was lying at the original trial. LeSage wrote Dangerfield’s actions were “just plain wrong.”

“The rationale was that since no explicit promise or favour was given the witness prior to his testimony, he would not be contaminated and not testify in return for rewards granted. The fallacy and disingenuousness of this position is that police knew that (he) was going to be rewarded… yet he was able, under this process, to totally mislead the jury.”

This was not the first time Dangerfield’s work was subject to scathing criticism. In a 2001 judicial inquiry into the Sophonow case, once again Dangerfield was found to have withheld evidence that would have weakened testimony from a Crown witness. “This was a serious error on the part of the Crown,” wrote former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Peter Cory, the commissioner for the Sophonow inquiry. “The error contributed significantly to the wrongful conviction.”

Perhaps most remarkable at this stage of proceedings is the extent to which the entire justice system — or at least those involved directly in this case — have gone to protect themselves and Dangerfield.

In the Court of Appeal testimony, both federal and provincial prosecutors claimed they could not recall the intimate details of the Ostrowski prosecution, even after being given an opportunity to review the documents in question.

Judith Webster, who would go on from the federal prosecution service to serve as the first female chief judge of the Manitoba provincial court, claimed she had “no memory of this file” even after reviewing her memos. She denied she knew the specific details of the deal with Lovelace, only that a deal was in place to stay the federal drug charges. She could not remember if she spoke directly to Dangerfield about the deal. Ostrowski’s legal team referred to her as “not a helpful witness.”

Webster’s boss at that time, Peter Kremer, was equally challenged when it came to remembering the specifics of the Ostrowski case. Specifically, Ostrowski’s legal team had hoped Kremer could have established the extent to which Dangerfield was consulted on the Lovelace deal.

Weinstein, one of the city’s best-known criminal lawyers, did not testify before the Court of Appeal, but in his 2009 testimony at the Ostrowski bail hearing, he was calm and casual and he described the process by which he negotiated a deal for Lovelace, asked that no written account of the deal be produced, and then claimed to have kept it from his client for nearly two years. Weinstein has continued to maintain he asked no one inform his client of the deal that had been worked because otherwise it would “taint his evidence.” He also continued to maintain there was nothing unethical about a practice that, in the Driskell inquiry in particular, has been universally decried as a manipulation of the justice system.

Finally, we are left with the testimony of Dangerfield himself. After trying unsuccessfully to avoid appearing before the Court of Appeal because of health problems, Dangerfield did testify. He continued to deny knowing anything about the Lovelace deal. Specifically, he claimed he “had no recollection at all of making a specific inquiry about the status of (Lovelace’s federal) charge.”

This claim is refuted by correspondence he penned during the 1987 trial, which certainly implied he was aware of the terms, and the fact all his co-workers have previously testified in other judicial inquiries a deal like this could not have been reached without his approval.

In their final submissions to the Court of Appeal, lawyer James Lockyer made this observation about the almost systemic amnesia suffered by the federal and provincial prosecutors who testified.

“These people did not live in bubbles; they worked on the same side of the justice system and in close proximity.” He went on to note the manner in which the deal was negotiated — orally, without written confirmation — “made unravelling the deal — who knew what and when — much harder. It created what may be termed a ‘veil of deniability.’”

The Court of Appeal has received a submission from Manitoba Justice to expunge Ostrowski’s original conviction and enter a stay of proceedings. However, the province continues to oppose Ostrowski’s request for an acquittal, arguing while he may have been denied a fair trial, it would be too difficult to try him now, 30 years later, and there is evidence suggesting he was involved in the crime.

The court will likely take some or all of the summer to reach it’s final verdict. In any event, Ostrowski will no longer be a convicted murderer.

The only other certainty seems to be others in the justice system who bear some responsibility won’t have to account for their roles. As we have seen in the cases involving Sophonow, Driskell and Unger, no formal action has ever been taken against Dangerfield, despite compelling evidence of dishonesty and deception.

Somehow, that doesn’t sound like justice.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Timeline

1986

Sept. 9: Jim Luzny arrested on drug-trafficking charges.

Sept. 13: Matthew Lovelace arrested on drug-trafficking charges.

Sept. 14: Frank Ostrowski arrested on drug-trafficking charges

Sept. 24: Lovelace calls Winnipeg police and says Ostrowski is planning to kill “a friend” that he describes as “the carpenter.”

Sept. 25: Robert Nieman is shot three times in the head as he returns to his apartment; Ostrowski arrested and charged same day with attempted murder. Robert Dunkley and Luis Correia are also arrested and charged with attempted murder.

Oct. 21: Nieman dies; charges upgraded to first-degree murder.

1987

May 13: Luzny acquitted.

May 23: Ostrowski and Correia are convicted of first-degree murder; Dunkley pleaded guilty just before the trial and was convicted of second-degree murder.

1988

September: Ostrowski’s conviction is heard by the Manitoba Court of Appeal

November: At Lovelace’s federal drug trial, prosecutors call no evidence and an acquittal is entered.

1989

February: Ostrowski’s appeal is dismissed.

2001

The Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted (now Innocence Canada) agrees to take on Ostrowski’s case.

2003

AIDWYC investigation uncovers evidence of a deal with Lovelace that was never disclosed to defence or jury; also discovers the Jacobson report that shows Lovelace’s tip to police was tied to another man he feared would be killed, not Nieman.

2009

July: An application is made to the federal Justice Department for a review of Ostrowski’s claims of innocence.

December: Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench orders Ostrowski released on bail pending review of his case by Ottawa.

2014

November: Then-federal justice minister Peter MacKay determined that based on the Crown’s failure to disclose “a significant amount of relevant and reliable information,” he was convinced that there was “a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice likely occurred.” Case is referred to the Manitoba Court of Appeal.

2017

Hearings begin at the Court of Appeal

2018

May: In its final arguments, Manitoba Justice tells Appeal Court it is willing to expunge Ostrowski’s conviction and enter a stay of proceedings. Ostrowski’s legal team presses for an acquittal.

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, May 28, 2018 10:26 PM CDT: Updates story to final edit