A sobering reality Drug addict who got clean behind bars grieves for sister who couldn't

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/05/2018 (2310 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

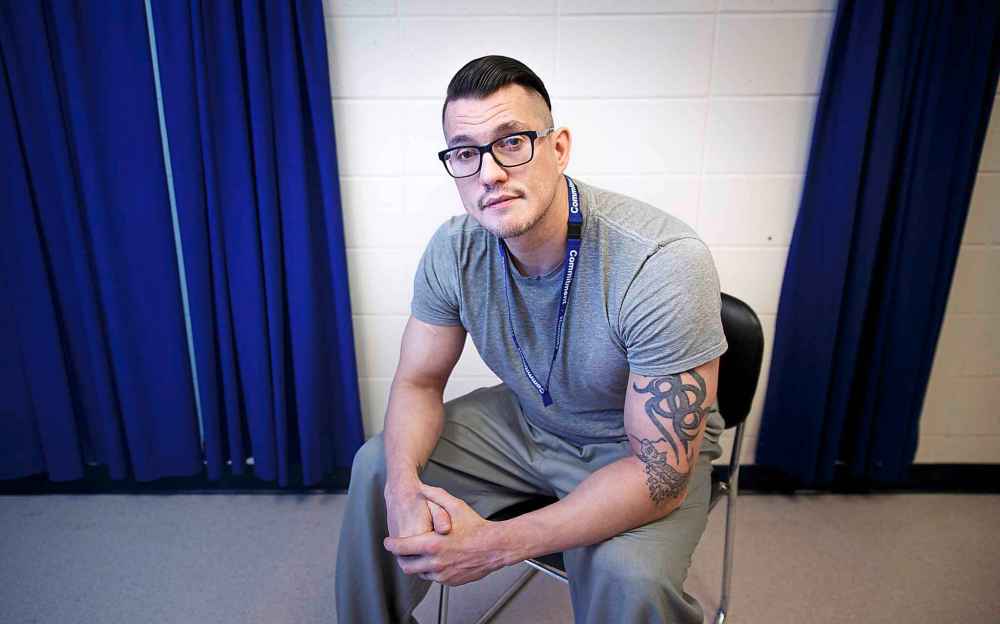

Nelson Berard was in jail, newly sober, when they told him his only sister had died of a suspected overdose.

“We need to have a word with you,” he remembers a program facilitator saying. It was April 18, sometime after 7 a.m., and he was sitting on his bunk in the Winding Rivers unit at Headingley Correctional Centre.

“S–t,” Berard thought, “am I in trouble?”

He wasn’t. They told him that his sister had been found dead the night before and that he had to call his mother.

He listened to her sob over the phone from her home outside Portage la Prairie. “My baby’s gone, my boy,” she cried. “My baby’s gone.”

For Berard, it didn’t quite compute.

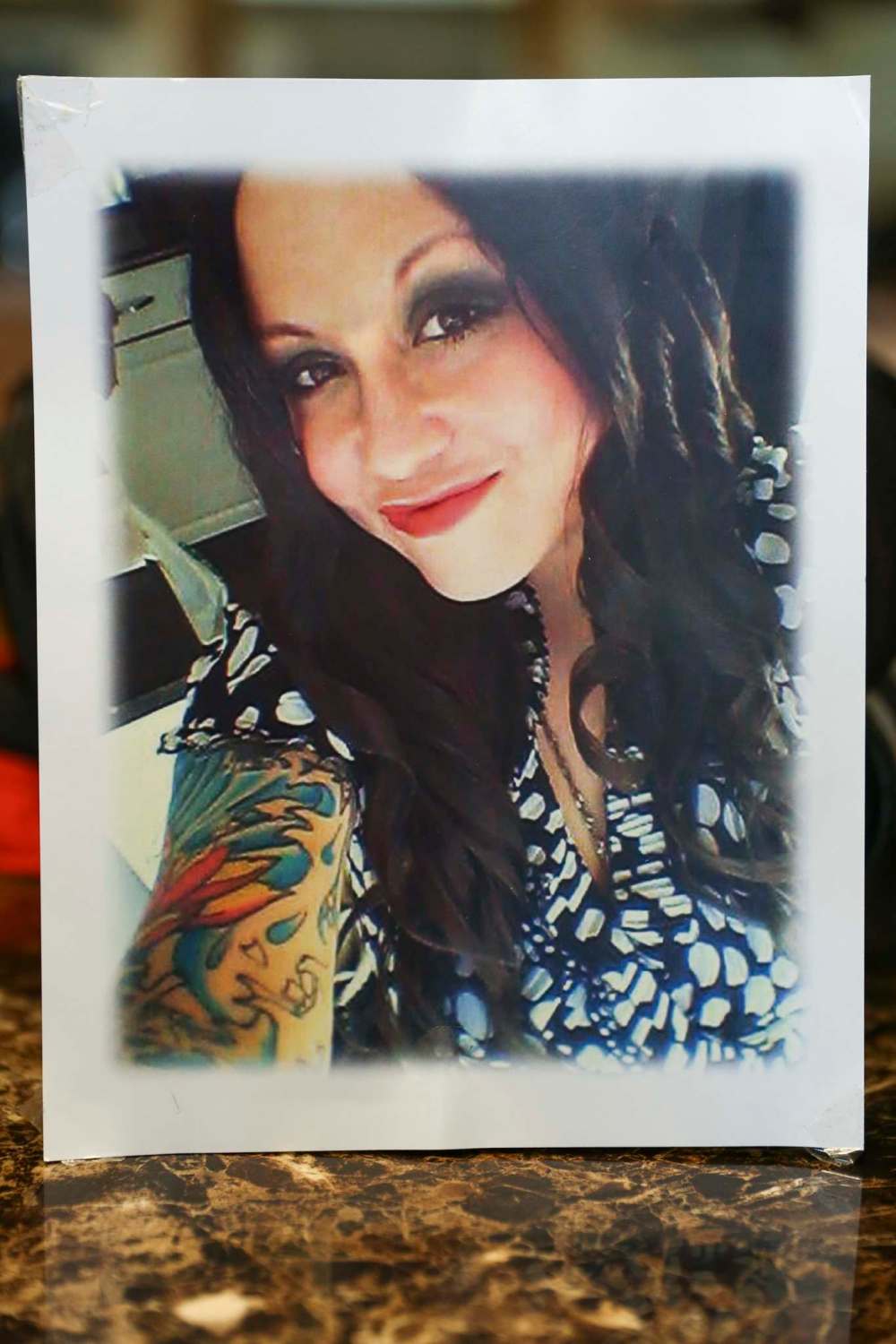

On one hand, it’s hard to mourn someone from jail because there’s nothing there of them with you — their smile, their voice, their soothingly familiar perfume. On the other, it was so unexpected. Margaret Lynn Marie Berard was an in-patient at a detox facility. Marie was an addict, yes, but she was getting help. How could you die from a suspected overdose when you had reached out to all the people who were supposed to help you get clean? When you were in a place where you were supposed to be safe from your own worst impulses?

There is an injustice to it that Berard and his mother, Linda Sheppard, turn over in their minds. It is hard for them to contemplate how Berard, in jail with so few options, could finally get clean, take ownership of his addiction and its myriad impacts, while Marie, with seemingly so many options and such a drive for sobriety, couldn’t get help.

“I’m not trying to abuse the system or lie to anyone,” Marie wrote in a letter to the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, dated four months before her death. In it she begged someone, everyone, to help her go to rehab, promising she’d excel there like she excelled in school.

“I’m scared,” she wrote, “but more scared to die with my story still in me and not told.”

The lives of Marie and her brother are twinned by childhood trauma, but diverge in adulthood.

He is a 40-year-old convicted drug trafficker, addicted to methamphetamine and cocaine, waiting for his next court date on charges of aggravated assault and armed robbery. Six months ago, he picked up a prison phone and an automated voice asked him if he wanted to participate in the Winding Rivers Therapeutic Community addictions treatment program at Headingley. Help was one “yes” away. Berard took it.

Marie died just shy of her 37th birthday. She’d been a functioning drug addict most of her adult life, a coping mechanism for childhood abuse, domestic violence and lifelong battles with mental illness. She’d been the first at work the day a co-worker had hanged himself, a moment Sheppard said her daughter could never erase. Marie was a devoted mother to her two sons and worked hard to better their lives, earning a health-care aide certificate from Red River College, a Native Studies diploma from Assiniboine College and another certificate as a hairstylist.

“She was always smiling,” Sheppard said, even as she quietly came apart.

Last week, the Manitoba government released the Virgo report, a 257-page document that outlines a new strategy for mental-health and addictions services. Flip through and you’ll find a graphic meant to remind you of a pinball machine: confusingly colourful with chutes and levers and springs that might lob you unexpectedly from one area to another, a trap door that might open suddenly at your feet.

It is meant to illustrate the many challenges people face when trying to access care and then when trying to navigate toward the services they need.

“There will be no easy fix,” the report warns. “These ‘rules’ of the pinball game will not be so easily undone.”

But they do need to be undone, Berard and Sheppard agree, if people like Marie are going to be helped.

Although she was a functioning addict for much of her life, Marie’s formal launch into Manitoba’s disjointed mental-health and addictions system was just a few years ago. An abusive former partner punched her so hard in the face she needed jaw surgery. Doctors prescribed the opioid oxycodone for the pain. She was hooked. Within a year she was frantic. Her inability to get the help she needed is reminiscent of so many of the stories and recommendations contained in the Virgo report.

“I’m buying pain meds off the street cause if I don’t I can’t move my jaw to eat or turn my neck, face throbs, so I got to do what I need to. But truth is, I worry at times for my heart to stop,” she wrote. “My doctor said two options: die or rehab.”

Marie went on methadone to treat her opioid cravings, and Valium for her anxiety. This past January she started at rehab. She wrote her family letters and diligently documented her experience in a bright-pink notebook. The inside pages were plastered with cut-outs from magazines. Save your life, fall in love, there are no shortcuts to the future.

On her third day in rehab, Marie wrote that she was anxious and shaky. “Felt so tired during the first group I fell asleep,” she wrote. “The days go by so fast and my cravings to use are getting less and less. But today I did have the urge but went and bought clothes and jewelry.”

Reading that makes Sheppard chuckle; Marie always did like buying clothes.

But the drug cocktail that made Marie fall asleep during her group classes eventually proved an impediment to the program she was in. They told her she would need to wean herself off of enough of the drugs that she could stay awake before they could help, Sheppard said. Marie wasn’t a quitter, so she went to detox.

This is the part where Berard vibrates with frustration. Whenever Sheppard visited her daughter there were people milling about outside smoking marijuana, offering to sell her drugs. Nobody searched his sister’s room or her belongings while she was there, nobody made sure she stayed safe while withdrawing.

“In a jailhouse setting you are forced to clean yourself up,” Berard said, then “when you’re clean your mind is different.”

Marie was found dead in her room with pills that she shouldn’t have had, her mother said. She’s awaiting the results of the autopsy, but Berard doesn’t need them to explain his sister’s sudden death.

“My sister purchased something and then went right back to detox to do it,” he said matter-of-factly, then quickly became angry, eyes watering. “Why was my sister allowed to leave?”

Marie tried to get sober but didn’t; her brother didn’t go to jail to get sober, but he did. This painful dichotomy is what made him want to share his story. He’s read snippets of the Virgo recommendations and is optimistic, enthusiastic even. That’s new.

When Berard arrived at Headingley he had what he calls a “jailhouse mentality” toward recovery, namely: “f–k it.” But he picked up that phone and said yes to Winding Rivers; his mom told him to do the program or he’d end up dead.

There are two units, one that houses between 80 and 85 inmates and the other 90 to 95, and they are separate from the general population. Days are structured starting at the same time, and there is a morning meeting and an evening meeting. Half the day is comprised of programming that includes cognitive behavioural therapy and relapse management; the other half is spent working — gardening for Habit for Humanity and refurbishing bikes, for example.

Winding Rivers is designed to allow for “social relearning,” said Sheryl Reid, the units’ manager.

“They’re learning from each other and they’re also learning from themselves,” she said. “Staff are working with them to really get them to be productive when they get out of here; that’s our goal, we’re trying to take out that inmate mentality.”

Berard said the community focus is what’s helped him the most. The men in his unit propped him up when he learned Marie had died, sharing their own stories of mothers and sisters they lost while in jail.

“It’s hard. I’m super vulnerable right now,” he said. “If I wasn’t in the (Winding Rivers) program when this all occurred I would be scrapping left and right, I know I would be, in anger.”

When Berard spoke he would occasionally twist a blue lanyard in his hand. It has the words “honesty,” “humility” and “commitment” on it, the core values of the first of the program’s four phases. The second lanyard is green for Phase 2, which Berard is currently in, and has the words “teamwork,” “willingness” and “tolerance” on it. Phase 3’s yellow lanyard reads “empowerment,” “responsibility” and “acceptance.” The lanyard from fourth and final phase is black with the words “leadership,” “confidence” and “change.”

“You can just see by the core values the expectation is holding them accountable,” Reid said.

The full program, which has been in place since 2012 and can handle 156 participants at a time, takes a year to complete, although since it accepts inmates who are both awaiting sentencing and who have already been sentenced, some people spend much less time in it. That’s both a positive and a negative, said Michael Weinwrath, a criminologist with the University of Winnipeg who was part of a team tasked by Manitoba Justice to evaluate the program in 2015.

“When you run a program in a provincial correctional facility you always have the problem of the fast turnover of the inmates,” he said, noting the overall evaluation was good.

Inmates who participated in the program were 71 per cent less likely to be arrested for any kind of crimes in the year following their release, compared with about 56 per cent of inmates released from Headingley’s general population.

“It was a positive place to do time,” Weinwrath said. “There were less inmate assaults, less inmates being moved out because they can’t get along. It promotes, I think, constructive relations between inmates which, in the end, is what you want to see them engaged in when they’re released.”

“In a jailhouse setting you are forced to clean yourself up,” Berard said, then “when you’re clean your mind is different.” – Linda Berard

The impact the program has already had on Berard was unexpected, Sheppard said.

“I was really surprised,” she said, to hear her son admit over the phone, after so long, that he is an addict. It’s Marie’s influence, she’s sure, that will keep him sober.

“All he can see is Marie laying in that coffin,” she said.

Berard went in handcuffs, shackled at his feet, to the viewing.

The chance to be a better brother is gone, but Berard said he could still be a better son, a better father to his two daughters, to his own son.

“I am so selfish on drugs. I have done it for 20 years. I didn’t care,” he said. ‘I love my kids. But I picked drugs over my kids, I picked drugs over family, over everything.”

Berard phones his mother four times a day from jail. Sometimes they cry, other times they talk about how suddenly they’ll inhale and smell the scent of Marie’s perfume. She wore patchouli and she wore it strong.

jane.gerster@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Wednesday, May 30, 2018 6:20 AM CDT: Adds photos