One dog at a time Animal rescue volunteers, vet with mobile clinic spend weekend on Manitoba First Nation in effort to reduce dangerous stray dog numbers By: Jessica Botelho-Urbanski Posted: Last Modified: Updates

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/03/2018 (2820 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

EASTERVILLE / CHEMAWAWIN CREE NATION — Standing on the harbour between Easterville and Chemawawin Cree Nation, it feels like you could be alone in the world.

Blankets of snow and ice stretch as far as the eye can see, freckled with trails from disappeared snowmobiles. All that’s audible is the sound of your own breathing.

Then you hear the barking.

Located about 475 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg, Chemawawin is one of 63 First Nations in Manitoba. Many grapple with an overpopulation of stray dogs.

Driving into and walking around the community in February, it often seems there are more dogs than people.

Dogs howling. Dogs strutting down the street. Dogs eating garbage. Dogs following in your tracks, wanting to play.

In reality, Chemawawin is home to about 1,400 people and there are about 30 more in Easterville, its neighbouring town. It’s near-impossible to count just how many dogs there are; the population fluctuates constantly.

This far north it’s difficult to access health services for people, never mind dogs, says Chief Clarence Easter. The nearest medical centres are in The Pas (about 200 kilometres northwest) and in Winnipeg.

That’s partly why Chemawawin’s council invited Manitoba Underdogs Rescue into the fray for Project Amber, a mobile spay and neuter clinic at Chemawawin School. It was MUR’s second time there. The clinic was orchestrated with help from Ashern’s Hudson Reykdal Veterinary Services, and the relationship between the community and the rescue organization is ongoing.

“It’s more of a health drive for us. We’re trying to provide access to services in the community, not just (for) dogs, but for people as well,” says Easter, the leader here since 1994.

He points to recently paved roads, new playgrounds and an anti-smoking policy as other parts of the health plan.

The council wants to “create an environment where people can be able to move around the community, without being afraid of dogs.”

“After 50 years now, we’ve relocated and the devastation happened,” Easter says in an interview at the band office.

He’s referring to Chemawawin’s forced move to the southeast shore of Cedar Lake in 1964.

Across the frozen harbour is where residents used to live, before the Manitoba government flooded their land to build the Grand Rapids Hydro station. Hydro built new homes for those who were displaced, but couldn’t recreate Chemawawin’s livelihood.

“We can’t change that. But we can change the way we live today and we can change the way we’re going to live next week, next year, 10 years or 20 years from now,” the chief says.

He was six years old at the time of the move. His community never quite rebounded, unable to live off the land as it previously had. But he’s hopeful for the future.

“We’re in a new location now. Let’s start over and whatever happened years ago happened,” Easter says.

“Now, I’m telling people, ‘Let’s turn a new leaf.”

The 18 volunteers from MUR start arriving Friday evening, most embarking from Winnipeg after working day jobs at offices, stores, schools, a dog-therapy centre, a chocolate shop.

They make the five-hour commute and fight the urge to fall asleep, starting by setting up dozens of kennels on one side of the school gymnasium floor. Air mattresses, cots and sleeping bags occupy the other half. A beige curtain is pulled down the middle to divide barks and snores.

It’s about 11:30 p.m. and anticipation is building for the weekend ahead.

This is MUR’s 14th mobile spay and neuter clinic since 2011. The volunteers have already visited Long Plain, Brokenhead, Sagkeeng, Ebb and Flow, Sandy Bay, Easterville and Westman First Nations and their last visit here was in November. So, for the most part, volunteers know the drill.

There are a few rookies this time though, including Orah Moss. The high school English teacher has fostered pups through MUR in the past, but wanted to do more.

“To be in a group of people who just donate three days, plus exhaustion time, just to do something for a bunch of animals they might not ever see again… I think that’s really cool to be a part of that,” she says.

On Saturday morning, Desiree Klippenstein starts by warning everyone to be prepared for “an emotionally charged day.” There’s no telling what’s in store or what kind of animal neglect may be seen.

Besides their work in the gym, volunteers take turns driving around the community looking for strays to bring in. Differentiating strays from owned dogs can be difficult; few of the pups wear collars and not many are leashed. Volunteers do their best to figure out who’s who with help from the community.

As one of the leaders in the crew, Klippenstein will deal with any rambunctious dogs and act as a liaison with the group’s go-to vet, Dr. Keri Hudson Reykdal.

“If anyone says anything that offends you, just let it slide,” she cautions before the clinic begins.

The volunteers huddle in the foyer for the initial debrief beside a mountain of handmade dog beds donated by a sewing circle. There are also nearly 200 bags — about 4,500 kilograms — of dog food piled opposite. Visitors will get to go home with a bag and a bed, plus a toy and blanket for their pet.

Easterville resident Jeff Thomas is one of the first community members to arrive with Cotton, his fluffy white Pyrenees, to be spayed. She has already birthed three litters.

Thomas says there’s still lots of trust to build between MUR and the community, although he’s already a fan of their work.

“A lot of people were a little hesitant (to bring their dogs in) because some people were like, ‘Well, am I going to get my dog back?’” he says.

“If we assure them and bring them in and show them, ‘this is what we do and how it works,’ people will be more receptive to the neutering program.”

A bit later, a man comes in to get his dog vaccinated but refuses to have him neutered.

MUR’s executive director Jessica Hansen tries to persuade him, but he won’t budge. She has heard every excuse in the proverbial book against spay and neuter. Many people say they want their dog to have just one litter.

“Every time a dog gets pregnant, that’s six to eight puppies, and a dog can get pregnant a few times per year,” Hansen says.

“We try to explain to them that their dogs will stay healthier if they are fixed and we try to focus on them bettering their community. It’s not just about them and what they want.”

● ● ●

Cotton, Afro, Bro, Becky, Chop, Twinkle, Chuncho, Bongo and Miskegees 1 and 2 are just a few of the 50 dogs getting spayed or neutered by Hudson Reykdal this weekend. Her team will also vaccinate even more animals.

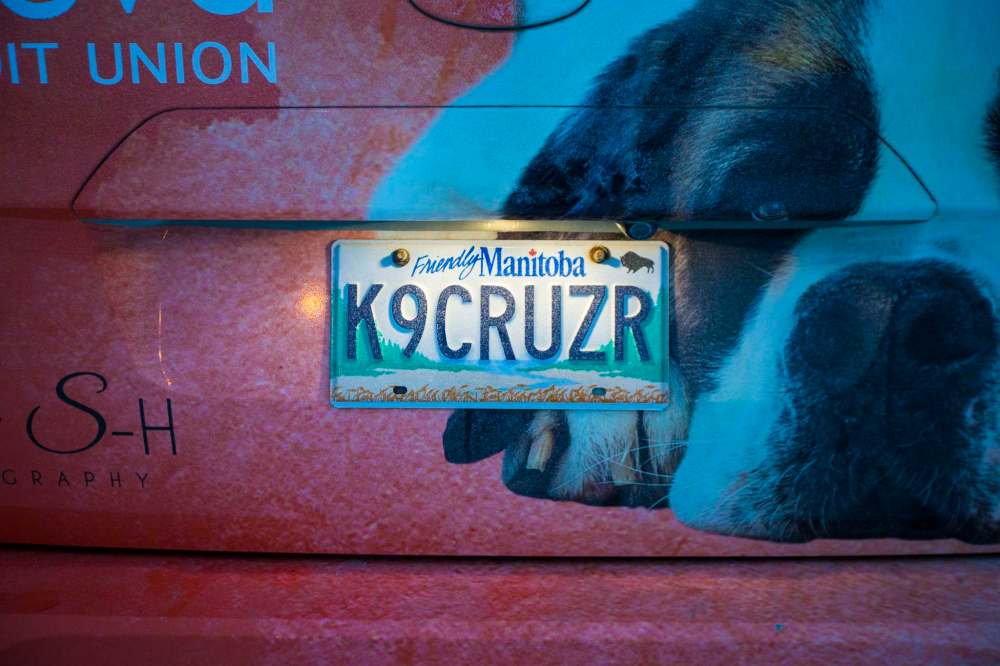

Ashern is nearly 300 kilometres south, but the vet’s custom-built trailer, made in Ohio, enables her to set up almost anywhere.

Increasingly, that’s meant helping in remote First Nations communities where the work can make a real difference toward public health and safety. Hence their current setup in the Chemawawin School parking lot.

Once Hudson Reykdal gets going in her mobile clinic she doesn’t like to stop, performing surgery on as many dogs as she can with military-like precision.

Her trailer walls are covered in whiteboards which, in turn, are covered with scribbled to-do lists: check breakers, drain tap, clean kennels, mop, charge X-ray, furnace on.

Reykdal’s surgery table is tucked in back, where a master bedroom might be in a typical RV. It’s still a comfort zone, as she snips, stitches and fields questions.

Interviews are nothing new for the star of Dr. Keri: Prairie Vet, her 10-part TV series, which finished airing its first season on Animal Planet last month.

“We’re trying to help them curb their dog population in a positive manner,” she says. “So by spaying and neutering, instead of the alternatives we sometimes hear about.”

The “alternatives” are dog culls, an option few here seem to want to mention by name.

wfpsummary:

Little Grand Rapids shaken by tragedy

Donnelly Rose Eaglestick, a petite, 24-year-old mom to one daughter, was killed by a pack of dogs in Little Grand Rapids First Nation last May. :wfpsummary

Little Grand Rapids shaken by tragedy

Donnelly Rose Eaglestick, a petite, 24-year-old mom to one daughter, was killed by a pack of dogs in Little Grand Rapids First Nation last May. The remote reserve is located 265 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg. Adults and children have been known to walk in the community with sticks as protection against wild dogs.

Eaglestick was returning home from a friend’s place early on a Saturday morning when she was attacked. Her body was found after daybreak by people on their way to work. About 30 dogs were spotted in the vicinity.

Judy Klassen, Liberal MLA for Kewatinook, said her husband was one of the people who discovered Eaglestick.

Klassen visited the community again last week as part of a northern tour before winter roads melt. She said families are still reeling over Eaglestick’s death.

“I heard there’s still some families who believe that the dogs responsible have not been put down. And then I hear that somebody was hired to go and kill roaming dogs,” she said.

Little Grand Rapids Chief Raymond Keeper said there have been three more dog-bite incidents since Eaglestick’s death.

It seems there are fewer strays roaming in the community than there were last year, Klassen said. But she is still annoyed with the way police dealt — or didn’t — with the situation.

“The thing that still irritates me is when the RCMP, who had the resources, could have gone out right away and hunted the dogs down,” she said.

At a local band office meeting, an RCMP officer told community members that police take care of animal-control issues only in extreme circumstances, she said.

“I was just shocked,” she said. “What do you qualify as an extreme circumstance? A young mother was torn apart.”

The province did not send conservation officers to help deal with the dog problem after the mauling, either.

A spokesman for Manitoba’s Office of the Chief Veterinarian, which enforces the Animal Care Act, acknowledged the risks feral dogs pose — from carrying diseases that can infect humans and other animals, to being aggressive towards people.

But the office would not commit to additional funding or animal-control action up north, although the office “strongly support(s) the efforts of communities to mitigate these risks.”

“However, it is important to note that animal-control issues are under the jurisdiction of the municipality or community, and it would be their decision as to whether an animal-control bylaw is required in their community and how to enforce that,” the spokesman said.

“We try to support municipalities and communities when appropriate and will respond to animal welfare concerns brought to the attention of the Animal Care Line (204-945-8000) by first-hand eyewitnesses.”

Though First Nations have final say over their animal-control bylaws, Klassen said there needs to be a balance struck between community autonomy and getting resource help from police and government.

— Jessica Botelho-Urbanski

RCMP and bylaw enforcement officers will kill strays when the population is getting violent or out of control. It typically occurred once a year, during the winter melt in March or April, says Easter.

That’s when the council starts to get “a lot of calls with dogs being all over the place, following the kids to school and things like that, roaming in gangs.”

But the chief doesn’t want to see culls ever happen again in Chemawawin. The last one occurred four or five years back.

“We want to stop doing that. We want to be able to catch the dogs and take them (away),” he says.

Strays gathering in packs and attacking people have long been concerns, but the problem took on new urgency last May when 24-year-old Donnelly Rose Eaglestick was mauled to death in Little Grand Rapids First Nation.

Construction crews found her body near a water treatment plant; there were more than 30 dogs nearby. That event was “always our biggest fear,” Easter says.

The chief says a video that went viral on social media two years ago also contributed to a change in thinking about the situation. An 18-year-old man from Easterville went to jail for throwing a puppy in the air. The dog suffered significant soft-tissue damage when it hit the pavement, and was nearly paralyzed.

About a dozen dog bites have also been reported on the reserve in the last year, according to Ann Catt, the local bylaw enforcement officer. The bites were quickly treated at nursing stations.

● ● ●

By Saturday afternoon, the MUR team encounters its first major surprise.

A shy wiener dog named Kirby, previously thought to be pregnant, was just stuffed with — wait for it — wieners. She had four undigested hotdogs in her stomach. Amusing, perhaps but expensive.

“There’s like, a $1,000 surgery right there. So that’s great,” Hansen says, sounding exasperated. “And we’re obviously paying for that.”

Kirby will be fine, but gets close attention (namely coos and cuddles) from volunteers for the rest of the day.

Sarcoptic mange has so far been the biggest health concern for dogs in Chemawawin. At their last clinic, MUR found about 90 per cent of dogs here showed symptoms of the skin disease, usually rashes and hair loss. The prevalence is lower this time around.

The disease is contagious for humans, though it’s treatable with antibiotics. No human cases have been reported in Chemawawin yet.

“We want to make the dogs’ lives better, but we also want to make the peoples’ lives better,” Klippenstein says. It’s all part of the public health puzzle.

Expenses are another major factor. This clinic alone cost about $12,000 to stage, money MUR raised through fundraising along with $20,000 donated by retail chain PetSmart.

There haven’t been any contributions from government at any level to MUR’s efforts yet, Klippenstein says, adding they are looking into grant possibilities.

The Chemawawin band office is offering to cover members’ spay/neuter and vaccination fees, about $20 for each dog.

The council also set up a raffle box and there are door prizes – two flat-screen TVs and Winnipeg Jets tickets —just to encourage residents to, at least, visit the clinic for consultations.

By Sunday’s end, MUR has picked up 60 adult dogs and puppies. Some are surrenders, others strays.

A few dozen dogs will be driven to rescues in Alberta and Ontario. The rest are dispersed among local rescues, including Manitoba Mutts, Manitoba Pug Rescue and D’Arcy’s ARC, to be adopted.

MUR hopes to come back to Chemawawin in another six months or so for a third clinic, where they’ll likely pick up just as many dogs.

They’ll also be back by the end of March, to pick up more animals and drop off more than 240 donated collars.

If they don’t come back regularly, the situation might never improve.

One Chemawawin resident is extra grateful for MUR’s support. Catt, the primary person in charge of bylaw enforcement, usually deals with stray or unruly dogs on her own.

Catt is responsible for ensuring residents follow five bylaws — about curfews, smoking, fire burning, peacekeeping and dog control — but the dogs take up much of her time.

“It’s almost like one person could be (just) a dog person,” she says.

She feeds strays near her home to prevent them from digging in other peoples’ trash cans for scraps. And she tries “to put the food not too close together, because they fight each other.”

Since Catt started in the role about a year ago, only two dogs have been registered, despite a request from council for all dogs to be licensed.

“We had it announced on the radio, but nobody’s come. Nobody’s taking it really seriously about that part,” Catt says, sounding defiant, her voice raising an octave.

“But that will be another task to focus on and tackle.”

Catt used to be afraid of rez dogs, not letting her own pup out of sight when she visited Chemawawin decades ago. “We didn’t want them ripping up my little poodle,” she says.

Now that she lives here, her goal is to open an animal shelter in the community.

A dog’s purpose in Chemawawin has evolved significantly over the last few decades, Easter says.

“It used to be that dogs played a major role in taking you around to places before. You’d have dog sleds. Dogs were a way of transportation 40 years ago,” he says. “Now the traditional way is they become your companions. They’re part of your family, as family goes.”

That closeness makes surrendering some of the animals even more difficult.

Coun. Russell Chartier makes the tough call to give up one of his furry family members, three-year-old Cedrick, described as “100 per cent rez dog.”

“He’s not very friendly and I’m scared for the neighbours and their kids, and all the rest of the people walking through my yard,” Chartier says. “It’s very hard. I’ll probably get emotional.”

Elizabeth Umpherville surrenders one of her four dogs; this one doesn’t have a name. She found him eating trash at the garbage dump last summer.

“I think he would be better off with another family that would give him the proper care that he needs,” she says before waving goodbye.

•••

In total, MUR has rescued 1,100 animals since it assembled seven years ago. But the group realizes there’s much more to do.

“Taking dogs in and out of communities is great and it helps, but it’s a temporary solution,” Hansen says. “We really need to help the communities establish better bylaws and help them get their populations under control.”

The chief agrees and says vets who provide spay and neuter services should be mandatory, though he’s not sure how they’d be paid.

“We’re here to stay and we need to be healthy,” Easter says. “And the dogs are here to stay and they need to stay healthy along with us. We’ve got to come to grips with that and we’ve got to deal with it in a positive way.”

At the school throughout the weekend, a few volunteers relay how they would rather be doing dog rescue and clinics like this as their full-time jobs, but they don’t want their names published out of fear they’ll lose their jobs.

It’s also taboo to get paid in the rescue community, says volunteer Kayla Simpson, because some people could get into it for “the wrong reasons.”

“But if they did get paid, they could do so much more,” she says.

Hudson Reykdal acknowledges having to actively avoid burnout. A lot of vets develop “compassion fatigue,” she says, adding she tries not to get too emotionally bogged down.

Before her shift begins at 7:45 Sunday morning she’s out driving around the reserve to see if the clinic has made a dent yet. Are there fewer dogs wandering around? Probably not.

As everyone else snoozes and snowflakes dangle mid-air, Reykdal spots a few strays.

She heads back to the school to start again. Her work — MUR’s work, Catt’s work, the chief’s work — goes on, with no end in sight.

“You can’t help the world, but you can try to help one community at a time hopefully,” she says back in the trailer. “Part of the job is knowing that you can’t help every single animal out there. You help the ones that you can.”

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @_jessbu

History

Updated on Friday, March 23, 2018 12:00 PM CDT: Updates thumbnail