Stark beauty, hidden scars Life is a struggle on God's Lake Narrows First Nation, but a will to overcome generations of hardship gives purpose

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/12/2017 (2910 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

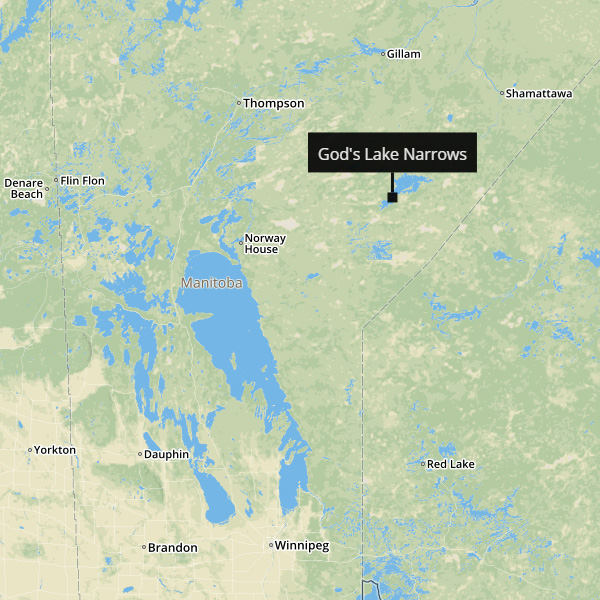

Free Press reporter Randy Turner and photographer Mike Deal travelled to God’s Lake Narrows First Nation in October with a straightforward mission: document everyday life on a remote, northern fly-in Indigenous community that only a fraction of non-Aboriginal Canadians would ever visit.

Canada has long been presented as a nation of Two Solitudes — the cultural and political divide between French- and English-speaking Canadians. Hugh MacLennan’s novel of the same name, published in 1945, was standard high school literature.

But to define Canada as a nation of two solitudes is a conceit that ignores the solitude that was here in the first place — the one experienced by Indigenous peoples.

Yet for generations, First Nations, mostly in the North, have existed in relative isolation. Their day-to-day lives, their shared history, unfolds in a world unrecognizable to the vast majority of Canadians.

In other words, true solitude.

The task for the Free Press journalists was simple; ask questions and listen to the answers. The openness and generosity shown by residents during the better part of two weeks was humbling.

● ● ●

GOD’S LAKE NARROWS FIRST NATION — Even after all these years, Wilfred Snowbird still wonders about the bullet.

Snowbird was just 16 that night, when he sat on the edge of his bed, hearing the voices that told him, “Nobody cares.”

Then the thought, “If I killed myself, where would I go?”

The short answer would be: not here, where his young life already seemed without meaning. His parents drank heavily. He had started down the same path, taking his first drink at age nine.

“You’re thinking that you’re not loved,” Snowbird recalls. “They (his parents) are too busy drinking. That’s all they care about. Nobody tells you they love you. You feel trapped. I wanted to get out of it, but I couldn’t.

“It was really hard… all you’ve seen is alcohol. It seemed normal to drink.”

So Snowbird came to a conclusion that night. “I wanted to end it there,” he says.

His attention fell to the .22-calibre rifle at the foot of his bed. It wasn’t loaded. So without really thinking, he checked his jacket pocket.

There was a bullet.

“I always question, ‘Where did that bullet come from?’” he says.

Where the bullet went, however, was the difference between whether Snowbird lived or died that night on the edge of his bed.

He turned the rifle on his chest and pulled the trigger. His grip slipped. The bullet entered his left shoulder. As Snowbird lay bleeding, his father burst into the room raging about what he had done.

He was medevaced to Thompson, where doctors thought his arm might have to be amputated.

“That’s the first time I prayed, asking God, like a friend,” Snowbird says. “He must have heard me.”

He tells this story, without a trace of drama, while sitting in his councillor’s chair in the God’s Lake Narrows band office, where phones are constantly ringing as constituents of this First Nation call with their own problems.

After all, no one has the market cornered on tragedy here. That includes the six-member council.

Coun. Larry Watt is 47 years old now, but he vividly remembers looking out the front window of his home, at the age of four, and seeing his father driving his boat in circles on the lake that boarded their property. Dulas Watt had been drinking, too, before he roared off.

Watt never saw his father alive again. He fell from his boat that day and drowned.

“There was a party in our house almost every day,” he says. “It was tough; we had our own clubhouse (in the bush). That’s where we used to sleep. That’s how bad it was.”

A few years later, Watt’s sister Sheila had gone missing on the lake, too. The next day, he and his brother went to the dock to scoop water from the lake.

He noticed something red about two metres down. It was Sheila’s lifeless body.

“I looked closely and saw her hair swaying in the water,” he recalls. Another of his sisters also drowned in God’s Lake.

Alcohol was involved in all of the deaths.

So it doesn’t take long into a 12-day visit to this isolated, fly-in community located about 550 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg to begin to understand the depths of unspoken loss. The scars are emotional, physical and lasting.

When he was younger, Watt would cut himself on his stomach and arms. “I was angry,” he says.

And Snowbird? His left shoulder has never let him forget about that bullet; where it came from and where it went.

“I still feel it,” he says. “It’s a constant reminder when I feel pain.”

It’s early October and the season is changing, winter is coming. The leaves are the colour of marmalade and the chill off the seventh-largest lake in Manitoba is beginning to bite.

There are 1,500 or so inhabitants of God’s Lake Narrows First Nation. About 80 more live on the adjacent “island,” which is not on the First Nation, so it’s governed by the province. The Northern Store, the RCMP detachment and airport are located there.

The fishing season that attracts tourists from across North America is over. Many of the men are out hunting moose. Children walk to and from school on a dirt road that runs like a spine through the community, which is made up of six “suburbs,” each consisting of one or two extended families, which explains why so many residents share common surnames.

Most mornings are slow and sleepy. The only major activity is the ongoing construction of a new nursing station.

In a small wooden building, Vicki Okemow sits behind a microphone and makes the day’s announcements on the community’s radio station, 97.1 on the FM dial:

“Thomas Clarke lost his bank card between the Northern Store and his house; west side, get your garbage ready; Geroy and Sara Hastings, hang up your phone; Pamela Chubb, phone Sheila.”

There are other messages, too; greetings, job postings, requests for donations for a headstone. “Anything that happens in the community,” she explains.

Okemow also takes requests for songs she plays via YouTube on her laptop. When the first request comes in for a rap song, she asks the caller, “Is it clean?”

“If there’s a swear word I cut them off right away,” she says.

Bingos from the community centre are broadcast, too, as are jamborees that are often held in a room adjacent to where Okemow is sitting. Only gospel music is played on Sunday and in the days after funerals.

“I love my community,” she says. “It’s a beautiful place. Our water is still clear and clean; fishing here is great.”

On the downside? The adults gamble too much, she says. The kids are hooked on their electronic devices. There’s not enough family time.

“I guess I just see it as a day-to-day thing,” she says. “We just try to do the best we can do. Nothing can be changed overnight.”

Of course, Okemow could be describing many Manitoba communities, north or south. Isolated or populated. Many families, too.

Sure, there are good times. A couple nights a week a crowd will gather to play a card game called ‘Bingo Poker’ in the band hall, where the air is thick with laughter and cigarette smoke. There are jigs once a month at the seniors home. Hockey tournaments and singing competitions are held during the long winter months.

But dig deeper, and it becomes as crystal clear as the water in God’s Lake that the wounds residents like Wilfred Snowbird carry are a stark reminder that what’s visible to the naked eye can mask untold heartache.

Just talk to them. Stories laced with tragedy are so commonplace they are often told matter-of-factly, with little or no emotion. A 20-something kid talks about the time he held his own intestines. A man walking along the side of the road talks about having his hand and jaw broken when he got mugged in Winnipeg.

Melissa Okemow, 35, talks about her 14-year-old daughter Harmony who, just over a year ago, hanged herself from a tree on Blueberry Hill, on the edge of the community.

For Melissa and her family, the anguish of youth suicide was all-too familiar. Born in God’s Lake, she lived in Winnipeg for several years before returning to the First Nation about 15 years ago. Not long after, her 14-year-old cousin, Buddy Jr., hanged himself in a closet. Only a few months later, on March 28, 2005, Buddy’s little brother Henry did the same thing. In the same closet.

Henry was eight years old.

“He was a cheerful little kid,” Okemow says of Henry. “When he hung himself it hurt the whole community. Why did he do that? He always had that smile.”

There were warning signs with her daughter, though. Harmony was cutting herself and refused to say why. “She was hiding something from me,” Okemow says.

It wasn’t until after Harmony died that her mother found out she had been raped. At the age of seven.

“There’s domestic violence in the community,” says Okemow, who now uses her Facebook page to provide support to other sexual assault victims and offers up her home as a safe house.

“There’s drinking going on with kids in the house; these kids are roaming around at night. When a Friday comes, I have eight kids at my house. (Parents) need to pay attention to their kids. I see a lot of kids being neglected. But I don’t want them to grow up saying, ‘F— the world.’”

At the cemetery where Harmony is now buried, the headstones tell stories, too. One man, age 30, murdered at the St. Regis Hotel in Winnipeg. Another died in a house fire at age 28. Another from overdose. And so on.

The cemetery, one of three in the community, was opened in the mid-’90s. Now there’s an entire field of grave markers.

“Too many of them,” Melissa says.

Sherilyn Hill lost her mother in a house fire eight years ago.

“There’s a lot of grief that we’re going through,” says Hill, 31. “One way or another, we try to be there for one another. The way I cope with mine is to visit the cemetery. I speak to them like they’re still here.”

Who does she speak to?

“The ones I miss at the moment,” she says.

Another story. A 21-year-old man we’ll call Michael doesn’t want his name to be printed. He’s standing in an enclosed front porch with two younger women, and he politely explains that his favourite activity is getting together with friends to hang out or ride a snowmobile.

“We like to get high and talk about things,” he says. “That’s our thing. Sometimes, we don’t even say anything. We just relax.”

Michael has a Grade 10 education, having dropped out of high school after a brief time in Winnipeg. He’d like to learn carpentry and build houses someday at God’s Lake. “People always complain about their houses,” he says.

Then he abruptly changes the subject.

“I have a story about gore,” he begins.

It was three years ago in Winnipeg, in the Balmoral Street area; Michael was stumbling home after a night of drinking and lipped off to a man riding past on a bicycle.

There was a scuffle. Michael felt two hard jabs to his ribs. The man jumped on his bike and pedalled away.

Michael says he stumbled home in a daze, and realized his intestines were outside of his stomach. He had been stabbed. While his cousin dialed 911, he passed out but was wide awake for the emergency surgery.

“It was like a movie, man,” he says, “but the pain was real.”

He spent five hours in surgery and another six days in recovery at Health Sciences Centre. He lifts his shirt and provides evidence, the large vertical scar that extends from his ribcage to his navel. It took 26 staples to close the wound, he says.

He could go on, he says.

“There’s lots left to say, but not enough time.”

And that’s the grim reality for the people of this and First Nations across the country. Because although Michael might only be 21, and Melissa Okemow 35, their life experiences are inescapably rooted in a history that altered their futures long before they were even born.

Yes, prime minister Stephen Harper apologized to the survivors of Canada’s residential school system in 2008. The Truth and Reconciliation report, along with a list of 94 calls to action, was released in 2015.

But none of it erases the past in places like God’s Lake. There aren’t enough staples to close some wounds.

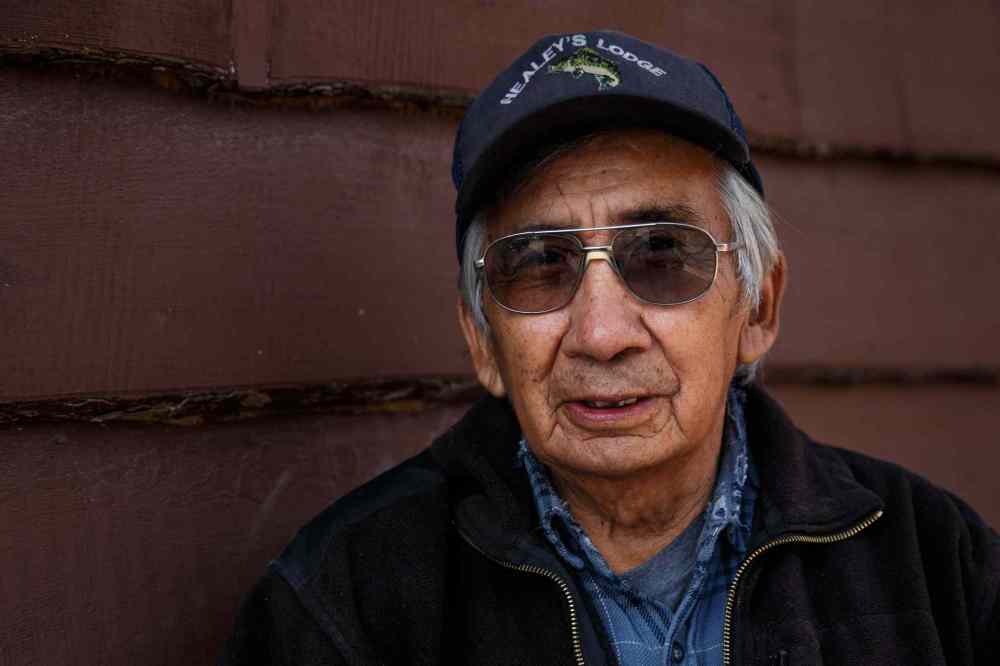

“I was born, baptized, raised and abused as a Roman Catholic,” says former God’s Lake chief Peter Watt, now 68. “That’s the story of my life.”

Watt’s father, Amos, was a special constable with the RCMP. He remembers “a lot of treasured memories as a kid before I went, the good times with my mom and dad.”

He was seven years old when he was put on a plane with other children. There were no seats, allowing more kids to be crammed in together.

“We were packed in there like sardines,” he said, repeating a story told by several other residents now in their 60s and 70s.

When the plane landed in Cross Lake, he saw men in black robes who spoke English and French. The boys and girls were separated.

“We weren’t even allowed to talk to our own sisters,” he says.

Watt was sexually abused. On those occasions, “I blacked out. And that’s all I want to say about it,” he says. “Normal behaviour for some of the pedophiles in black robes. And I’m not just talking men, too. Nuns.”

Peter’s brother Louis was sent to Cross Lake first. Now 74, he still vividly recalls the flight, on a Norseman single-engine bush plane.

“That’s one thing I’ll never forget,” he says. “When they first put me in the airplane I jumped out crying. They had to throw me in three times and hold me down. No seats. They ship you like cattle.”

There were 16 children huddled together on the plane, he says.

The sexual and physical abuse and general cruelty that the children endured wasn’t talked about when they returned home in the summer.

“Even if we told them there was abuse, they wouldn’t believe,” Louis says. “They (priests) were supposed to be holy people.”

Adds Peter: “You didn’t talk about the residential schools. You know why? Do you have to ask? It’s the shame of it.

“I came back after 10 months a stranger to my mom and dad, to my siblings. By the time I adjusted it was time to go back again.”

Arthur Williams, now 68, was sent to Norway House for Grade 8. Another “sardine” on a float plane who said his parents were helpless to keep him at home.

“They had no authority,” he recalled. “You had no choice but to let your kids go. They must have felt sad for quite a while. They weren’t used to seeing their kids go to different areas. I thought I was never going to come home.”

The impact of hauling children off to residential schools unleashed a systemic chain reaction that reverberates still in many families. In the case of Peter Watt, for example, it instilled the learned behaviour that discipline is the only method of teaching.

“We didn’t have the ability to parent,” he says. “We didn’t know how to show affection.”

Watt eventually returned to God’s Lake, married and raised four children. He worked as a band constable, a fisher and at a sawmill. He says, proudly, that he never received welfare.

Was he a good father?

“As a provider, yes,” he says. “As a father showing affection, no. I never learned to hug until a few years ago.

“(The residential-school experience) had a lifetime impact.”

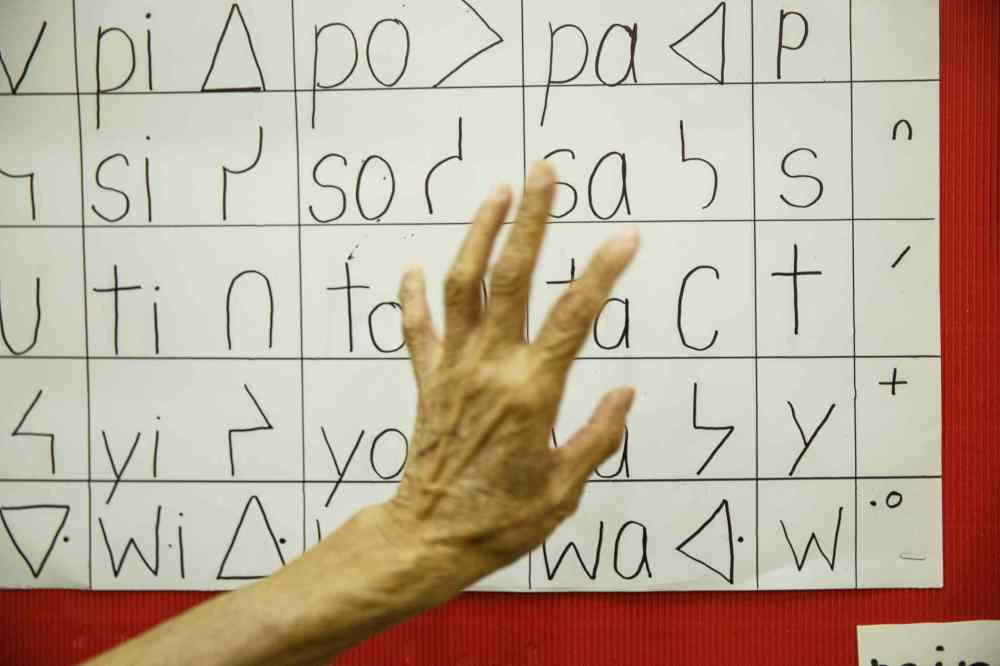

Language and cultural lifeline

Marion Mason does her best each day to introduce Cree children to their own language

The Cree language teacher at the God’s Lake Narrows School is a tiny woman with kind eyes and a perpetual smile.

Her name is Marion Mason and she’s 72 years old.

Mason raised nine children and received her bachelor’s degree at age 49.

“I was very proud,” she says.

These days, Mason does her best each day to introduce Cree children to their own language, which has been largely lost through everything from residential schools to iPads to indifference.

Up on the walls, there are lists of Cree words that Mason has her young pupils recite each day. “Tansi” —How are you? — for example, which Mason encourages students to ask their parents or grandparents at home, to encourage conversation.

“I’m trying to bring Cree back,” she says. “That’s our language, and we need to keep it alive. That’s our identity. We are Cree. If they don’t pass it along, it will be lost.”

Still, Mason’s classroom is but one small interlude in an environment where her students are immersed in English; the language of their television, their social media, their parents.

The children in this kindergarten-to-Grade 9 school — regardless of their heritage — usually have little to no introduction to their native tongue outside of this classroom.

“It’s very important,” Mason says. “They’re losing it. They don’t even understand when we talk to them, even some of my grandchildren.”

But keeping Cree alive is just one of myriad challenges facing educators here.

First, there’s a shortage of teachers, who are paid significantly less than their southern counterparts.

There are approximately 360 students in the school, which employs 26 teachers and 20 teaching assistants. Director of education Daniel Delorme says there are more than 30 kids in many classes and he could easily use five more teachers. The turnover rate is high.

But Delorme says it’s difficult to recruit potential educators when the salaries, set by the band council, average at least $20,000 less than what other Manitoba school divisions pay — and that’s not even factoring in additional costs for food and travel.

Look no further than the provincially overseen public school in God’s Lake, just off reserve, which has only about a dozen students. The minimum Class 5 salary in the school (which serves non-band families) is just over $62,000. The maximum for the same level is more than $93,000.

By comparison, the minimum Class 5 salary at the First Nations school is $46,000, the maximum just shy of $69,000.

“How are you going to get stability if you don’t pay your teachers?” Delorme reasons. “Education is such a valuable thing to have. It’s the real way out. Good teachers cost good money. That’s the bottom line.

“It’s sad, it really is.”

Delorme cites a Grade 5 teacher — whom he described as “A-plus” — trying to save money to travel home to Toronto for Christmas, which would mean spending upwards of $1,500 when airfare and other costs are factored in.

Add taxes, and the cost of groceries that can cost three times what they do in the south.

“You can work in Tim Hortons and get that kind of money in Winnipeg,” he says. “I’m scared that she’s going to go home and stay home.”

Consider that he’s been trying to hire teachers since September and has received only one response — from a retired teacher looking for a part-time job.

“It’s not that this community has a bad reputation,” he says. “It’s just that the salary is too low.”

There is also the ever-present issue of band politics. God’s Lake Narrows School principal Eli Campbell, who was just settling into his first year at the school, recently asked for an extra day during the Christmas break for travel from his home in Campbell River, B.C.

The band members overseeing the school refused and Campbell has resigned. Delorme is now interviewing for a new principal.

On the surface, the atmosphere in the hallways of God’s Lake Narrows School is not unlike any other K-9 environment, teaming with smiling, rambunctious children moving in a line from class to class.

“I see kids in the building, they have so much potential,” Delorme says. “The majority of these kids are good kids, super kids. They always smile even though you have to consider that about 80 per cent of these families are below the poverty line, even though they get welfare.

“They don’t always have the best of meals or food at home… but the majority of kids will give you a smile in the hallway and say hello. They want to learn, these kids, but sometimes they have (education assistants) taking care of them who aren’t trained teachers.”

Another thing holding students back is their own notion of potential, Campbell says before leaving the community. Ask a group of Grade 5 children what they want to be when they grow up and the replies are striking, he says.

The children who do have aspirations often limit their options to professions they know: teacher, nurse, police officer, truck driver, fisher. Rarely are other professional occupations such as lawyer or doctor mentioned.

“They can’t seem to put themselves in that light,” Campbell says. “They don’t have the role models. Some of them don’t see the opportunity, so they don’t see (education) as a saviour.”

Campbell is a white man who was born in Calgary. Delorme is from Ahtahkakoop First Nation in northern Saskatchewan.

“You’re the principal,” Campbell says students have said. “How can that Indian man be the boss of you?”

Delorme says the goal is not just to educate the children, but “make them proud of who they are.”

The latter objective is crucial. Because of all the challenges educators face in God’s Lake, by far the biggest hurdle is out of their control entirely: sending young teenagers away to attend high school.

This year, for example, there are 35 children attending Southeast Collegiate in Winnipeg. Another 15 are at Cranberry-Portage, north of The Pas. Most stay in school residences. A handful of others are boarded in Winnipeg and Thompson.

The numbers are not encouraging: Campbell says there are 31 students in Grade 9 classes at his school in early October. Of that number, about 25 will graduate. Maybe 13 will attend Grade 10 elsewhere. Of those, on average, nine or 10 will return.

Until recently, it was not uncommon for a single student from God’s Lake Narrows First Nation to graduate from Grade 12 in any given year.

Imagine being a 14-year-old Indigenous student raised in an isolated northern community surrounded by friends and family, suddenly uprooted to an urban environment populated by total strangers, and be expected to adapt, let alone excel academically.

One God’s Lake resident, now 35, says he was sent to a high school in St. James. He would often skip class and walk down to the shore of the Assiniboine River “just to hear the water.”

“You wake up every morning (at home) listening to the waves,” says the man, who declines to give his name. “You’ve got to hear water. Even the birds.”

He was three credits short of graduating when he left to go back home.

“I couldn’t take it anymore,” he says.

That culture shock claims the majority of kids, who feel far more isolated than they ever did in their own fly-in community. Many can’t go home to spend the holidays with family because of the cost; a one-way flight from Winnipeg is about $370.

“They get into the city and they’re alone now,” Campbell explains. “They don’t have support, they don’t know where they fit in. They go into it with a built-in fear for what they’re going to experience.”

The loneliness often leads to bad decisions.

“That’s a huge problem,” says Molly Menow, whose job at the school is to track the progress of some 400 off-reserve students each year. “It’s the No. 1 issue. They’re only 14, 15 years old. There’s always the peer pressure to do drugs and alcohol. They have to grow up and learn to make the right choices.”

So, for many, the answer is a simple one: go home. Of the 50 students who left for high school at the start of the current school year, more than a dozen were back at God’s Lake by the end of the month. “One day four of them got off the plane at the same time,” Campbell says.

There is hope, literally on the horizon, as ground has been cleared to build a new K-12 school on the First Nation. It will cost an estimated $50 million and take three years to complete. The new facility, which will accommodate up to 550 students between the ages of five and 21, could also help lure needed teachers.

Until then, however, a bitter irony remains in a community that is still ravaged by the trauma of residential schools.

“Residential school is still here for us,” band councillor Wilfred Snowbird says. “We send our kids out to complete strangers. Nobody’s watching them. It’s hard to sleep.”

Larry Watt, the band councillor, says it took him years to come to terms with his anger, and the feeling that his parents had abandoned him. His mother was a residential school survivor and so were his uncles, Louis and Peter Watt.

“I understand now,” he says. “The effects of colonization, residential schools. Our people were cheated. Even my mom wouldn’t talk about what really happened. And that’s how it was in the whole country.”

Janet Fox, a self-described facilitator who teaches seminars on traditional family parenting on First Nations communities across the country, is at God’s Lake the same time the Free Press is visiting.

Born on Samson Cree Nation in central Alberta, Fox contends that residential schools didn’t just adversely affect large swaths of the Indigenous population; it affected their children. And it continues to affect their children’s children. The evidence is self-evident, she says.

“This generation has spent their entire lives healing,” Fox says. “And it’s continuing. We keep losing our children. We fill up all the prisons, child welfare, group homes. We were taught we were savages. So we lost our ways. Our traditional teachings, our language. We really strayed from there. Slowly we’re making our way back.

“The biggest thing is loss of culture,” she adds. “How many children here even know they’re Cree? We need to make them so strong in their identity that when they go to Thompson or Winnipeg they’re able to face adversity.”

Like Peter Watt, Fox says she offered little emotional affection to her own children. “There wasn’t a lot of hugging, mostly material gifts,” she says. “That’s all I knew.

“What did I pass on to my children? Pain? Guilt? That’s what it’s about, generational trauma. It’s been a cycle for 150 years. The spirit has been so damaged and it goes around, and around and around.”

How can that cycle end?

For Larry Watt, a father of six with wife Charlene, it was a sweat lodge workshop he attended in Cross Lake in 1999 after deciding he wanted “to make a change, especially for my kids.”

“It felt so beautiful,” he recalls. “Words can’t express it. So peaceful. That’s what I was missing in my life… my connection with my spirituality. That’s when I started searching.”

More sweat lodges followed. Vision quests and fasting. Sharing circles. Traditional teachings Watt had to leave God’s Lake to discover.

“That’s where I found myself,” he says. “Who did I pray to? The Creator. You can call it God. I asked for guidance, for a better life.”

For Wilfred Snowbird, it was the determination to ensure that his four children, who are now between the ages of 15 and 25, were raised in a loving environment.

“I don’t want them to grow up like I did. I try to set an example,” says Snowbird, who has been married 25 years to his wife Leanna. “I tell them I love them all the time. And I teach them to forgive. What happened in the past is gone. I want to use that for good now.”

Other efforts are ongoing, in particular to convince elders — whom Larry Watt contends were “brainwashed” at residential schools — to welcome back spiritual traditions.

It took two years for council to finally approve the sweat lodge that now sits in Peter Watt’s backyard. There is an annual Sundance ceremony in God’s Lake.

And every summer for the past 15 years, several youths canoe and portage to and from Norway House, replicating the original trail travelled by band members since the early 1900s. It’s called Canoe Quest.

“They get an understanding of how their ancestors survived,” Watt says. “And also get away from the booze and the drugs, the negative influence, to connect with nature, the land.

“Get them to feel where they came from.”

Where else, after all, can you find a social program, available to God’s Lake residents, where couples and families can go on moose-hunting weekend expeditions to foster unity with each other and with nature?

Fox, too, says more elders who were convinced in residential schools that traditional healing was “bad medicine” are slowly coming around to the old ways that she teaches.

“Communities that have been resistant are finally accepting,” she says. “People are more open now. They understand that it’s identity that will help heal the people.

“Today’s generation has a lot better opportunity than we had growing up; today we can write our own history. The history books I grew up reading portrayed us as heathens and savages.”

Yes, history. It’s a lesson Peter Watt can summarize in just a few sentences.

“Custer wasn’t massacred,” the former chief says with a glint in his eyes. “He lost. You know the difference, right?”

RCMP Cpl. Mike Duke is cruising slowly along the dirt roads of God’s Lake and notes the residences that have kept him busy during his 22-month stint here.

“Problem house, problem house, problem house,” he says, pointing. “Been there, been there, been there…”

Duke, 49, has been a Mountie 24 years, and he’s served in several fly-in First Nations communities in Eastern Canada and Nunavut. His heritage is Anishinaabe, from the Chippewas of the Thames in southern Ontario.

When Duke first arrives at a First Nations community posting, he asks about traditions and customs. “If I’m stepping out of practice,” he tells them, “please be kind and tell me.”

Duke is operations superintendent on a 10-member staff that also services God’s River, located about 50 kilometres to the northeast, but much of his time is spent on patrol in God’s Lake. There are also five First Nations safety officers in God’s Lake Narrows, and another three in God’s River.

Many of the calls to the RCMP are drug- or alcohol-related, he says. And echoing what urban police statistics in the inner-city show, most involve chronic offenders.

“I don’t think it’s a violent place,” he says. “It’s not. The majority of our investigations are on a small portion of the community.

“People are people. They’re the salt of the earth. Even with the tragic things going on I see the love that they have for one another.”

Still, Duke is fully aware that he and other officers are dealing with the societal issues outlined in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings that stem from the ruinous actions of government and church.l

And the RCMP.

“It’s systematic,” says Duke, who is in the process of transferring to Little Grand Rapids. “There’s a lack of resources and supports. There needs to be reconciliation. (TRC chair) Justice Murray Sinclair said that very clearly in his report.”

Duke’s personal mantra follows the TRC conclusions, too: remember what happened, take ownership and build a better future.

“That’s what I try and do every day,” he says.

And the boiling point is inevitably fuelled by alcohol. God’s Lake is a dry community, but that’s a meaningless term. The winter road is a pipeline for both liquor and drugs.

Year-round ‘road to hell,’ or a path to prosperity?

Perhaps nothing divides the residents of God’s Lake Narrows more than the prospect of one day having an all-weather road linking the isolated First Nation with the rest of Manitoba year-round.

Perhaps nothing divides the residents of God’s Lake Narrows more than the prospect of one day having an all-weather road linking the isolated First Nation with the rest of Manitoba year-round.

The people who support the proposed road believe it will bring prosperity. Those against believe it will bring “hell.”

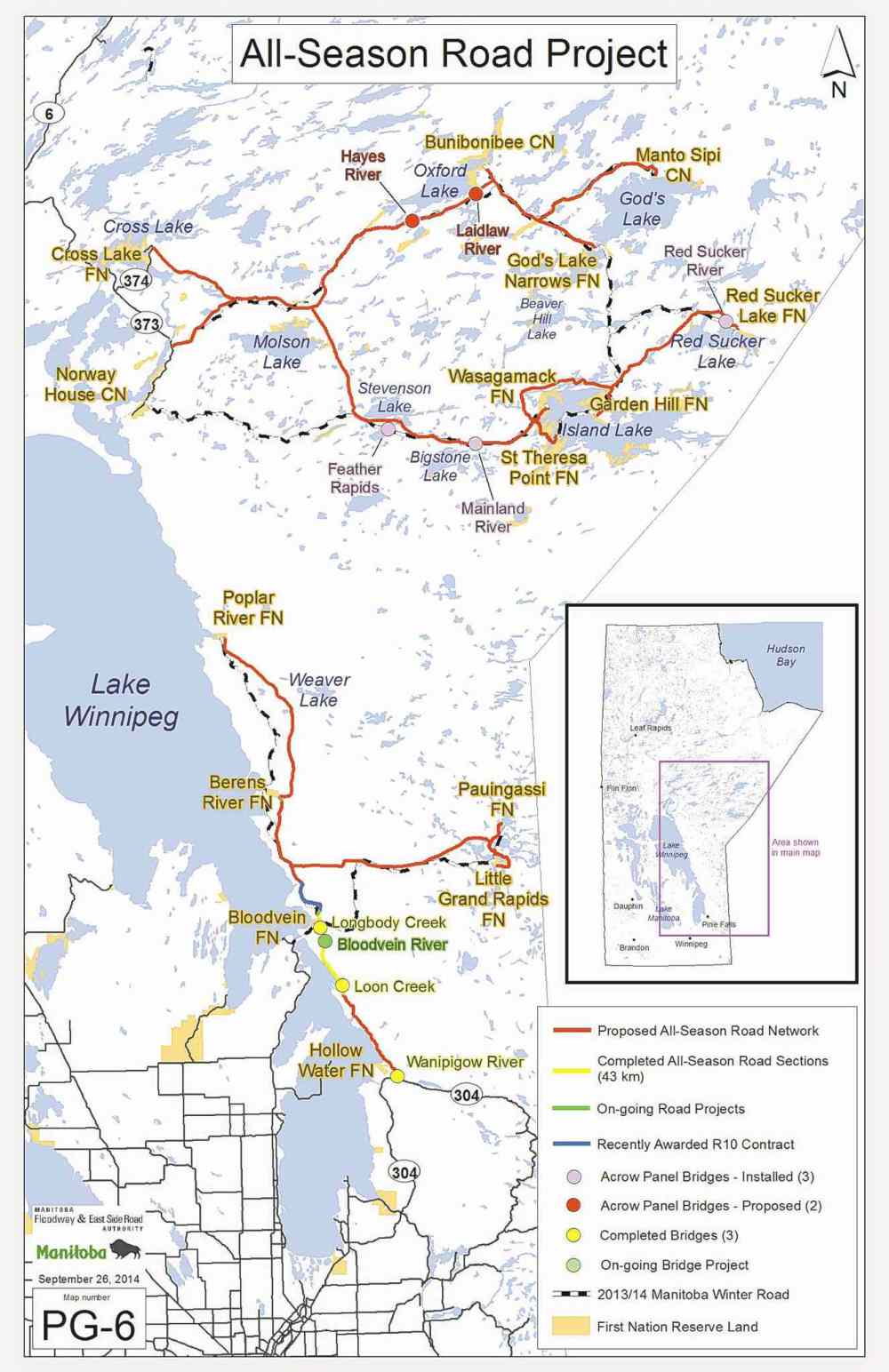

The former provincial NDP government began construction on a permanent road network to link 13 communities on the east side of Lake Winnipeg in 2011. The 1,028-kilometre project was estimated to cost approximately $3 billion and be completed in 30 years. The Pallister government has not yet made a commitment to continue the project.

The network is divided into two sections. The southern part starts at Provincial Road 304 near Hollow Water and threads 150 kilometres north along Lake Winnipeg, connecting communities such as Bloodvein and Berens River (completed in late 2017), along with Poplar River.

An east-west extension is designed to branch off north of Bloodvein and run 93 kilometres to the communities of Pauingassi, Little Grand Rapids First Nation and the airport at Little Grand Rapids.

The northern section of the network would be a 650-kilometre road starting at the northeastern tip of Lake Winnipeg near Norway House and Provincial Roads 373 and 374. The road would go east and split into a Y section at Molson Lake, with one arm ending at God’s Lake Narrows, and the other passing through Island Lake and on to Red Sucker Lake.

Opponents point out the majority of drugs and alcohol flowing into God’s Lake Narrows arrive via the winter road.

“There’s going to be a lot of sickness, a lot of depression,” says Molly Menow, who works as a counsellor at the First Nation’s kindergarten-to-Grade 9 school.

“It will be the road to hell. The world is going to enter in.”

And that’s why the prospect of a year-round link has raised fears in the community.

“Especially the elders, isolation makes them feel safe, says band councillor Wilfred Snowbird.

Former band council member Leona Okemow says she was initially opposed to the road, too, “because our land and our lakes would become tainted. We have such beautiful land and fresh water.”

But she eventually agreed with council to approve the road after the majority of residents voted in favour of the project.

“As a leader, I had to go with what they wished for,” she says.

God’s Lake Narrows Chief Gilbert Andrews says a road could open up the region for job-creating industries, such as mining and timber-cutting.

“I know a lot of people look at the negative part of it, which is drugs and alcohol flowing in freely,” Andrews says. “(But) It will create jobs. Tourism. This place was full of Americans all of the time. We used to have four or five lodges on the lake. Now there are only two.”

Goldie Healey, owner of Healey’s Lodge, says the road would alleviate two of the biggest economic challenges now facing community residents: the cost of food and airline transportation.

“We pay so much and… it’s so hard on people,” Healey says. “The freight costs are so high. But if people had the road, they could go in their trucks to Thompson or Winnipeg or Norway House. That’s a lot of money.

“We’d get more people out, too. They can’t afford to take their kids on Perimeter (Airlines). If you have five or six kids, you’re looking at $5,000 return (trip).”

The Selinger government predicted that once the all-season roads were in place, the cost of transporting goods and supplies to the communities would be cut by 50 per cent, while the cost of medical transport would be expected to shrink by 40 per cent.

A 26-oz bottle of hard liquor can fetch up to $150. A water bottle filled with vodka can go for $120.

Then there’s the more economical option, known locally as “juice,” which is a crude mixture of sugar, yeast and water — left to marinate at least 24 hours, then flavoured with beans or orange juice — that is now a growing problem.

Up until the last year, juice would often be made in large tubs that were shared at house parties, Duke says. But the arrival of gallon milk jugs at the Northern Store allowed for the homemade alcohol to become both marketable and portable.

“They used to make it in the bush and then go out and get it,” he says. “Now it’s a cottage industry. People are selling it. It’s underground. It’s black market, it’s prohibition.”

Snowbird says jugs of juice sell for $40-$50 each, a handsome profit in a community where the unemployment rate is upwards of 85 per cent.

But attempts to control or curb bootlegging are complicated, Snowbird says. It’s a small community. The identities of the people making the liquor and selling the drugs are not a well-kept secret.

However, RCMP can’t raid the homes of suspected drug dealers, and band police don’t have the resources to shut down operations. More often than not, council members try to reason with drug dealers, in particular, about the harm they’re doing to children.

“There’s a lot of tragedies,” Snowbird says. “All that weight falls on you. There’s nothing much we can do. We can talk to (the bootleggers and drug dealers). It’s like they don’t have a conscience. They don’t care. It’s a big problem.

“Drugs are not supposed to be here, since it’s such an isolated community. But crystal meth is here. Now cocaine. Prescription drugs.”

Patrolling the winter roads would be nearly impossible, he says. Besides, another not-well-kept secret in the community is that there’s often no one inspecting check-in baggage on Perimeter Airlines flights (the only airline serving many Manitoba fly-in First Nations) on the weekends.

“The plane is always packed because they know they can bring in anything,” he says. “It seems nobody cares about the amount of drugs flying into our community. People from the city use people from here (as drug mules).”

Carlos Castillo, vice-president of commercial services for Perimeter, insists the airline runs all baggage through X-ray scanners for all flights.

“We have cut down substantially the amount of contraband going to the community,” he says. “The machines are operating on all flights. We believe we’re doing an excellent job.”

Castillo acknowledges, however, that unlike security at major airports, security guards for Perimeter are not allowed to do body searches on their passengers.

And there’s another problem: councillors are members of a small, intertwined community. They know who the troublemakers are, but the drug dealers know them, too.

“Sometimes, I worry about my kids, my family,” Snowbird confesses. “You don’t know how these drug dealers or bootleggers will react.”

There are residents who says alcohol abuse was a much bigger problem in the 1970s and ’80s. And others who say that for too many in the community, nothing has changed.

Mary Okemow was born in 1945 on Elk Island, just northeast of God’s Lake Narrows. Along with her husband, Louis Jack, she raised five children in a log cabin on the lake. They got by on the land, hunting and fishing.

“It was a good life,” she says.

She speaks softly, sitting at her kitchen table. She looks weary. And she is reluctant to talk about her time at a residential school in Norway House from age 11 to 16, which she describes as “an open wound,” or the loss of her daughter a few years ago.

“It hurts,” is all she’ll say.

Okemow has eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren now. But she laments that the younger generation is not as disciplined or active.

“It wasn’t like this before,” she says. “Not like today. They (younger generation) don’t behave. No respect at all. That’s what I see around these days. They don’t do anything. Kids are bossier. I don’t know.

“There’s too much bad stuff. You see drunken people every day. Even the kids, they’re just roaming around. They’re not doing anything to help their parents.”

As if on cue, there is loud banging on the front door. A man stumbles in, mumbling incoherently. He reeks of alcohol. Okemow raises her voice to him and he becomes momentarily quiet.

“That’s my son,” she says with an audible sigh.

The man sits down at the table, yelling incomprehensively and waving his arms, but not violently.

His mother is standing now, slumped against the kitchen counter. This is a daily occurrence, she says.

“That’s why I feel like moving away sometimes,” she says. “I don’t know where.”

She calls out and a young man appears from the living room. His name is Chad and he’s Okemow’s son’s nephew.

Chad, in his early 20s, wants to be an electrician or a plumber but dropped out of high school in Winnipeg after one year. He was homesick and felt isolated.

He says his uncle is a good person, but ends up in his current state every time the welfare cheques arrive.

“It just makes me think I don’t want to be like that. Ever,” Chad says.

Okemow, still slumped at the kitchen sink, says, “Now you see what I mean?”

Outsiders who’ve never set foot in an isolated First Nations community might, at this point, ask why anyone stays here where there is so much pain, so few opportunities for employment and so many people living below the poverty line.

Wrong question.

“They’re full of baloney,” says Chief Gilbert Andrews, who has heard such questions before.

“They just take everything for granted because they’re down south. They’ve never been up north. All they see are the natural resources coming out of the North, not the people. If we were treated like Manitoba citizens instead of wards of the government we’d be much better off.

“I don’t think people should have to leave here. Before all this western culture came in everything was fine. No need for welfare. People knew how to live.”

Andrews’ position is straightforward: a society that forced his ancestors to live on a plot of land, then tried to strip away their entire culture and inflicted the damage of residential schools has no right to even suggest those same people should now abandon their communities because of the systemic, generational suffering that same society created in the first place.

They live here. Their family members are buried here. And their roots stretch back to when the treaty establishing the First Nation was signed with the Government of Canada in 1909.

Andrews, 60, spent eight years in Norway House residential school, followed by two years in Birtle and three years in Portage la Prairie. In the summers, in his teens, he was placed with farm families in Ontario. He was sent there to work and was paid only in room and board.

“I didn’t think about what was happening to me or why it was happening to me,” Andrews says. “I accepted it as a part of my life. That’s what made me come back and stay here forever. When I went into politics in 1986 it was for personal reasons, not to help the community. I didn’t think that way at that time. I thought this might be a way to get back at the system that put me through that ordeal.

“Now I’m there to protect our people from the same system. I try to keep them (government officials) honest and on their toes.”

Andrews has been chief for 14 years — and was a councillor before then — and oversees an annual budget of about $13 million.

“But that’s nowhere enough to look after the community,” he says. “We’re forever falling behind.”

For example, he says, the community has a fire truck, but nowhere to house it. “It’s no good when it’s 40 below and the fire truck is outside,” he notes.

Housing is in constant shortage, with up to 20 people living in a three-bedroom dwelling. Last year, there were 100 applications for housing from residents, Andews says. The federal Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation approved the construction of six homes.

The majority of residents still rely on sewage pickup and water delivery. Larger structures, like the school and nursing station, have their own sewer and water lines. A couple houses have no running water at all.

It’s the children’s future, however, that concerns Andrews the most.

“We try to turn it around, but the alcohol part, the drugs….kids turn to it, even though there’s education programs about that,” he says, noting that the community has a youth centre, but no programs or co-ordinator. “We have a hard time getting our youth out to tell us what they want. When we call a meeting only one or two show up. It’s hard to read their minds, you know?

“But I think kids today are so preoccupied with their electronics stuff. You talked to them, they don’t hear you. They have their earphones in. I think we’ve lost our cultural identities, our cultural abilities.”

Still, there’s no shortage of God’s Lake residents who refuse to give up on their community.

Curtis Bee, the 29-year-old co-ordinator of Bright Futures, which oversees domestic and family violence programs, doesn’t sugar-coat the realities he sees first-hand every day, but that hasn’t stopped him from trying to make lives better.

When Bee was a teenager, he was often left to tend for his two younger sisters. He didn’t complain, he managed.

“All I cared about was helping my young siblings, that they weren’t hungry, they weren’t cold,” says Bee, who now has four children of his own. “They were taken care of. It made me who I am today. When there’s struggle, I’m not one to give up. It may be be slow but I’ll still get there.”

After high school, Bee took adult education classes. He got a job with social services. Now he works to get youths involved in sports programs, hunting trips, medicine-picking camps and teaching them how to prepare fish and stretch furs. “For those who don’t have anyone to teach them, but want to learn,” he says.

“It’s not only my view to get in touch with our old ways,” Bee adds. “Everything is too modern. What if everything goes to s— tomorrow? How are we going to survive?”

Leona Trout, a community co-ordinator who helps collects Christmas gifts for the kids who might otherwise go without, understands the challenges, too.

“We are survivors of the residential school ourselves and we have to deal with it alone,” she says, while treating a couple of guests to a fireside meal of fried Klik and bannock. “What about the next generation? There’s no support groups.”

That past, Trout says, affected “the way they ate, the way they slept, the way they acted, the way they talked. The people of this place need healing. They need to get more understanding of their background, the traditional ways.”

But, she adds: “Our people are very friendly. Very respectful. They have big hearts.”

Trout lives in a four-bedroom bungalow that houses 10 family members. There’s a litter of puppies under the back porch being weaned by a stray dog.

“You get to go out and do your own thing,” she says of her community. “Awesome scenery. It’s quiet. And you know everybody… it’s like one big family.”

She means that literally. When she lost her parents years ago, one of her neighbours told her, “You’re more than welcome to call us Mom and Dad.”

She still does, to this day.

Her hope is that when the new K-12 school opens, more of the children will graduate, then perhaps pursue careers in nursing, justice or social work.

“They can all bring that back here to work with their own people,” she reasons.

Lorraine Trout, a child and family services worker in God’s Lake, adds: “I wouldn’t trade anything for my community. We’re solid in that unity. When something happens, the community comes together. You have that compassion for them. It’s a close-knit family here, in spite of the other problems out there.”

Goldie Healey has seen this togetherness since she arrived with her husband John from Newfoundland in 1968. He was a principal, she was a teacher and they brought their two young sons with them. They first settled in God’s River before moving south to God’s Lake in the early 1980’s.

“It looked so beautiful,” she says. “We thought we were in heaven.”

She remembers that residents watched over her family like hawks. “There was nothing but love and kindness in their eyes,” she says. “I loved it right from the beginning and still love it. I’m so at peace here. A lot of contentment and well-being.”

John died a few years ago, and now Healey runs a lodge, visited by construction workers and anglers, where she still fixes lumberjack meals for her customers three times daily, while her cats Skit and Skat roam about with impunity.

All these years later, the petite, patrician woman from Newfoundland has a passel of grandchildren and great-grandchildren underfoot in the lodge, representing the third and fourth generations of her family living in God’s Lake.

Others stopped here for a short time and never left either.

Nancy Ferguson was just 24 years old, and had never been on a plane when she flew into God’s Lake in 1977. “I was terrified,” she remembers.

Ferguson was raised in Brockville, Ont., but came to northern Manitoba after seeing an ad for a teaching position in the Globe and Mail. When she arrived at the teacher’s quarters, located off reserve on the island, there were no phones, no television, no bridges. The way on and off the island was a barge in warmer months and snowmobile or walking during the winter.

But the residents, she says, were as warm as the winters were cold.

“The people were so wonderful,” she says. “They were so kind and friendly. They’d give you the shirt off their backs.”

Soon after, Ferguson met Bello Okemow, a man raised on the traplines who one day screwed up the courage to ask the teacher out for a snowmobile ride. He sent her chocolates on Valentine’s Day and took her camping and fishing.

In 1978, Nancy and Bello married. They raised two children, both grown, and have 11 grandchildren.

“I came here to teach one year,” she says. “It’s been 40 years now. I never dreamed it, but I never wanted to live in a big city.”

Her husband, now 73, still tends his trapline and stays nights at the old family cottage in the bush.

“I love the outdoors,” he says. “That’s what my parents taught me. They used to tell me, ‘When I’m gone, don’t be sorry. The generation goes on and on.’”

Their son Duncan killed his first caribou at age 11. Duncan’s son is already a regular out on the trapline.

The generation goes on and on.

Brian Bee turns off the outboard motor, and the fishing boat sits in the unusually still and silent waters just off the shore of God’s Lake Narrows.

In the distance, you can hear the loons calling and dogs barking.

“Did you hear that?” Bee asks as water gently laps against the boat. “You know the loon’s talking to you, eh? You have to go far away to find that peace.”

Bee, 51, has come a long way to find peace, too. He’s a former gang-banger who openly admits to terrorizing the community in his youth.

“We shot up the town,” he says. “Shooting up the street lights. We started all the trouble. We started all the gangs. We scared people. I took so much from the community. We were just trying to survive… the older crowd.

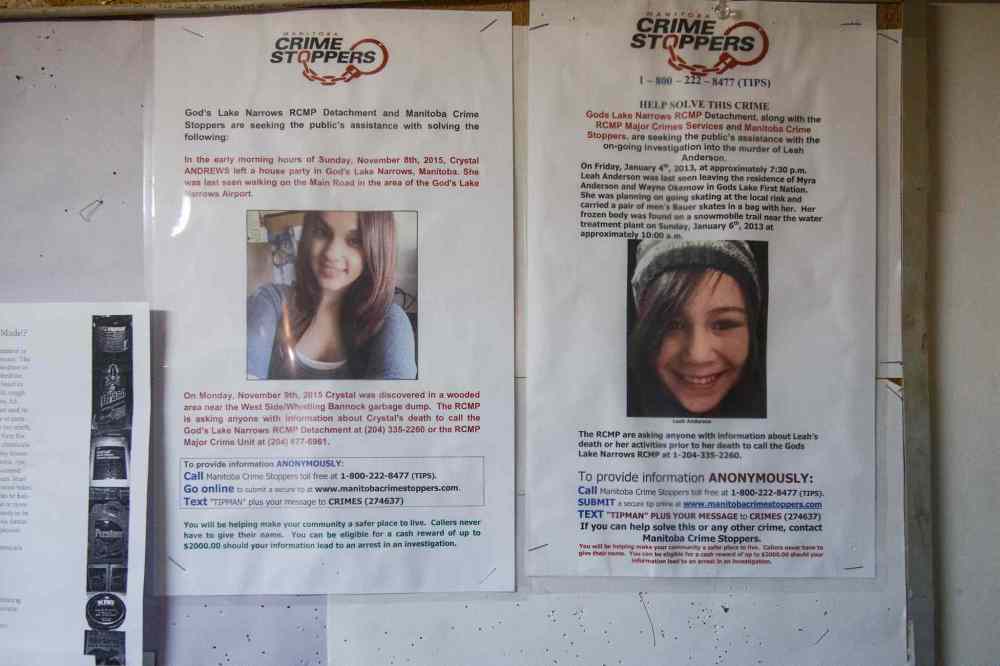

Young women’s unsolved deaths rattle community

People in God’s Lake have expressed fear, confusion and frustration over the unsolved deaths of two young women.

There is a white cross standing where Krystal Andrews’ body was found in early November 2015.

The cross is beneath a canopy of white birch and spruce trees, down a bumpy path on the edge of the town’s garbage dump. A small red New Testament, covered in plastic, hangs off the cross, as does a rosary.

There are other offerings, too; candles, a photo of Andrews — who was 23 when she died — and a purple wreath.

Andrews was last heard from when she called her boyfriend to tell him she was on her way home from a friend’s house. She never returned. Her body was later found by trappers in the secluded area where the cross now stands. RCMP immediately described Andrews’ death as “suspicious.”

On Jan. 4, 2013, Leah Anderson, 15, left her aunt and uncle’s home in God’s Lake for the local arena at around 7:30 p.m. She was alone, carrying her skates. Her last Facebook post to a friend, shortly before leaving, was “hey hey hey! you you you! how are you.”

Anderson’s body was found two days later on a snowmobile/walking trail, just on the edge of the lake. According to RCMP, she had been brutally beaten.

“Somewhere between between her door and the arena, Leah met her killer,” the RCMP said, in a Twitter/Facebook post.

To date, no charges have been laid in either case, although the RCMP investigations continue. RCMP are confident that the killer was male and known to Anderson, and there was “clear evidence that she had tried to defend herself during the attack.”

In a twitter statement, the RCMP added: “Several suspects came to the forefront right away, but one by one, were ruled out through investigative avenues. Other suspects were identified during the course of the investigation and ruled out after successfully passing a polygraph. Investigators were able to rule out numerous community members after DNA samples were collected and analyzed.”

In July 2017, police arrested a 23-year-old in Anderson’s death, calling the development “significant.” But the man was released shortly afterwards.

RCMP spokeswoman Tara Seel was asked if, given his release, the man was no longer a suspect.

“No,” was the reply.

People in the community have expressed fear, confusion and frustration over the unsolved deaths of the two young women.

“People were panicking, scared,” said God’s Lake councillor Larry Watt. “They don’t know who to blame. A lot of rumours going around. A lot of parents are scared to let their daughters out at night. They don’t know who to trust anymore.”

Wayne Okemow, Anderson’s uncle, told the Free Press that his niece was outgoing.

“She trusted people,” he said. “It has taken a toll on us as a family. “It has brought us a lot of sorrow and traumatic stress. Who did this to an innocent young girl who had a lot to live for?”

Okemow questions the RCMP’s investigation, claiming investigators have not been forthcoming with details of any progress being made.

“They’re not telling us the truth,” he said.

Robert Bee, Andrews’ grandfather, said the two deaths, with no closure, have led to widespread tension.

“We’re still grieving because of that,” Bee said. “There’s still fear. And also a sense of injustice. Sometimes, it even gets to the point of animosity. There’s accusations. Some of it can even be hate and revenge.

“I try not to expose my bitterness over it, but sometimes it surfaces, because she didn’t deserve it.”

Since Anderson’s homicide, RCMP have repeatedly asked for community members with any information to come forward.

“We continue to encourage anyone, particularly people living in the community of God’s Lake Narrows, who has information related to Leah’s death to contact RCMP,” Seel said.

But Bee noted some residents don’t trust the police. Others fear for their safety if they come forward with information.

“People don’t want to be considered a rat,” he said. “If they tell, they will be beaten up or excluded. They don’t want to tell on each other.”

God’s Lake chief Gilbert Andrews also questioned what he considers a lack of progress in the cases.

“I don’t know why they (RCMP investigators) haven’t laid any charges,” Andrews said. “I don’t know what they’re waiting for to tell you the truth.”

Sheila North Wilson, Grand Chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, said the deaths of Andrews and Anderson reflect the larger issue of missing and murdered women in the Aboriginal community, and the struggles still facing First Nations in general.

“Leah Anderson had dreams of being a leader,” Wilson said, referring to Anderson’s position on her school’s junior council. “Now she’s gone. She might have been a great leader but we’ll never know because of everything that culminated in her loss of life.”

“Those were dark times. You know what alcohol does. Bad things happen.”

Now Bee calls himself one of the “Fish Warriors,” a group of guides who assist tourists in locating the wealth of enormous walleye, northern pike and trout that populate the lake.

His transformation, he says, was the result of his grandfather passing on his knowledge of not only hunting and fishing, but sharing with the community. And keeping the family safe.

“You know what my character’s built out of? Old people’s way of life,” he says. “That’s what it’s going to take for these people to survive. We’ve got to start doing more. We’ve got to go back to those things. I’m going back to that way. I’m going to live like that until I die, probably.”

Bee dries and smokes his own catch. Some he sells, some he gives away. It’s part of his reparations. “That was my way of giving back,” he says.

Now with eight children of his own, he is determined to raise them in a different environment, too.

“There was no love and hugs in my time,” he says. “I’ve made a lot of improvements. I’m not as hard as I used to be. I tell my kids I love them all the time. And they sense that. Our home is very peaceful inside. No chaos. I’m so rich in what I have.

“This is why I always pray. I ask the Creator to forgive me for all my sins. I ask for his blessings for all of us here. I always ask him for safekeeping for everyone here.”

Bee is a big man and he speaks in a deep, monotone voice. Before heading back for shore, he tells the story of a loon that last year spent all winter on the lake. It didn’t leave; digging itself a hole under a dock to survive the brutal conditions.

“People thought the loon was crazy,” he says, chuckling at the analogy of his story.

What if — just like 16-year-old Wilfred Snowbird — an entire population of Canadians thought that they weren’t loved, that no one cared? What if they felt trapped and wanted out, but couldn’t find the way?

“We’re all survivors,” the Fish Warrior concludes. “There’s lots of broken people here. That’s why I don’t leave them.”

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @randyturner15

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, December 30, 2017 11:28 AM CST: Slideshow removed.