And the bands played on From crumbling wall to near-collapsing floor to crippling finances, the West End Cultural Centre has survived three decades and is still going strong

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/10/2017 (2967 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

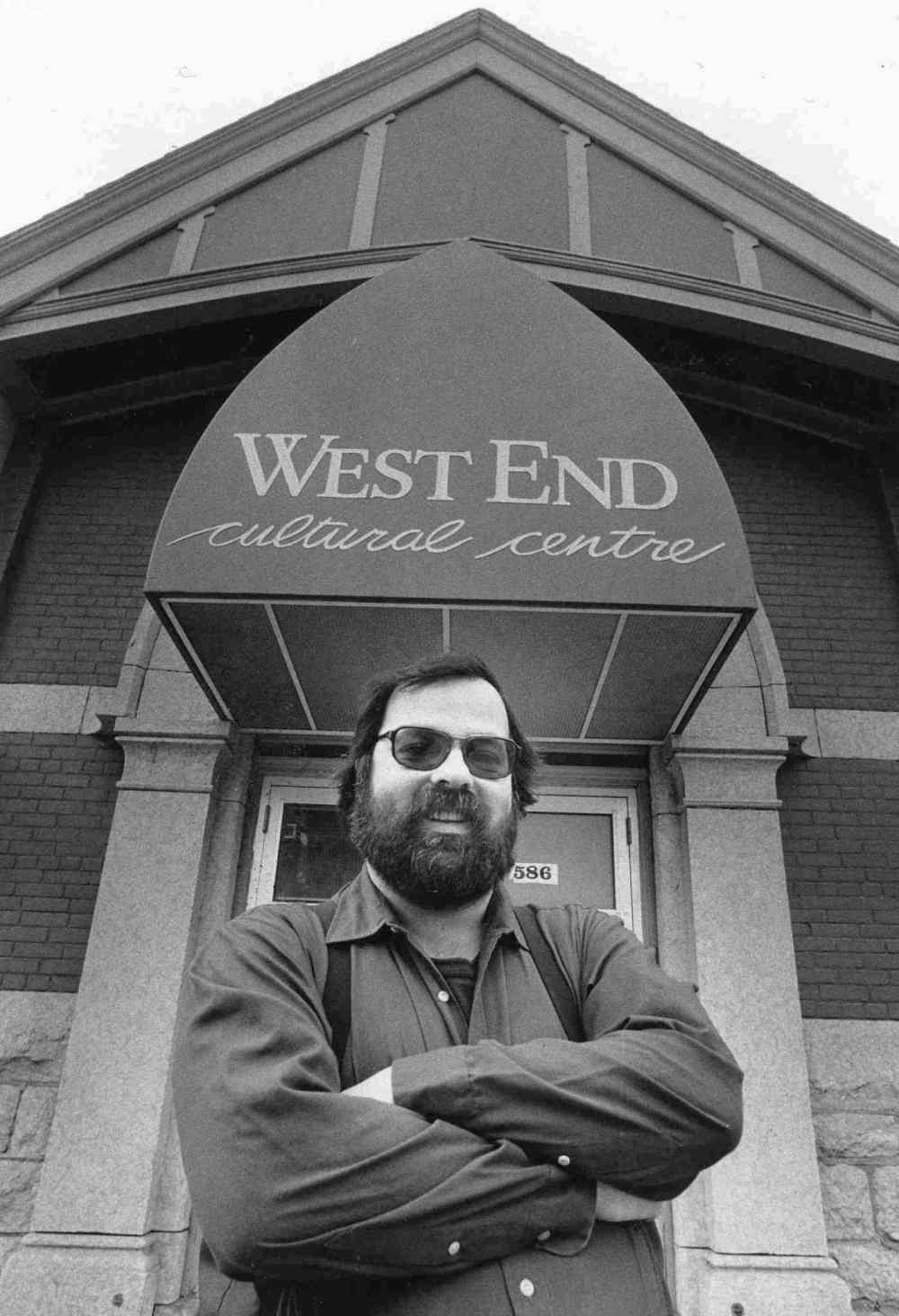

Back in October 1987, a ramshackle old church on the corner of Sherbrook Street and Ellice Avenue reopened its doors as the West End Cultural Centre.

The paint was still drying on the walls when patrons first walked through the doors and heard live music in what would become one of the most cherished listening rooms in the country.

Depending on who you ask, the first show at the West End happened on either Oct. 22, 26, 27 or 28 that year. (According to the Winnipeg Free Press of the day, it was Friday, Oct. 23.) The only thing known for certain is Spirit of the West performed, and it was nothing short of a miracle the venue opened on time for that show.

No matter the actual date, the 30th anniversary celebrations have been in full swing all month at the West End Cultural Centre, culminating Oct. 28 with Not By Bread Alone, a multi-generational tribute to the venue named after a piece of writing composed by founder Mitch Podolak that was the spark to set the whole WECC plan in motion.

Thirty years later, and the WECC is an indelible fixture of the Winnipeg music community. Ask anyone who has ever been onstage or in the audience and they’ll likely repeat a variation on a theme: it’s a special place.

From house of worship to worshipping fans

Before it brought a generation of live entertainment to Winnipeg’s West End, the unassuming building at Sherbrook Street and Ellice Avenue had been a cornerstone of the community since 1909.

It was an early home to many well-known city churches, starting with St. Matthews Anglican Church.

St. Matthews was created in the sparsely populated West End in 1896 as a mission of Holy Trinity Church. The following year, parishioners Mr. and Mrs. Horace Buley purchased and donated the lot at the corner of Ellice and Sherbrook on which the church built its first permanent home, a wooden structure with a capacity of 350 people.

Large-scale urban development came to the West End starting around 1904 when the city sent in surveyors to properly lay out streets and boulevards and the street-car system was expanded to include the area. In the next few years, thousands of new residential lots were put on the market.

The resulting population boom was reflected in the size of St. Matthews Church’s congregation. By 1907, the old church, with its popular Sunday school program and sports league, was bursting at the seams. A new home was desperately needed.

Rather than find a new location, the congregation decided instead to buy two adjacent lots for a sum of $5,000 and build their new church on the site of the old one. A final service was held at the old church in September 1908 and then were relocated to a nearby empty retail space.

The cornerstone for the current building was laid on Oct. 17, 1908, by Archdeacon Octave Fortin, the long-time rector of Holy Trinity Church. Construction went smoothly under contractors Pattinson and Eilback of Furby Street and the building was finished by the end of the year.

The church was designed by architect Herbert E. Matthews. The London, Ont., native practised in his home town for over a decade with about 100 projects to his credit, mostly large houses, before relocating to Winnipeg in 1905.

Here, his mainstay remained houses for wealthy clients but he did take on a few larger projects. Aside from what is now the West End Cultural Centre, other notable Matthews buildings that still exist include the Wardlaw Apartments on Nassau Street and the Congress Apartments on River Avenue.

Matthews’ design for the new church was in the Gothic Revival style, the most telling feature being the narrow, lancet windows. It was a popular style for churches in Canada at the time. Underneath the present-day blue paint is a façade of red brick with Tyndall stone trim.

The chapel area could hold 650 people and included a full basement to house the Sunday school classes and sports league.

The cost of the structure was $11,000, which swelled to over $15,000 by the time it was fitted out with furnishings, including a pipe organ.

The first service was held in the new church on Jan. 10, 1909.

Despite its much larger capacity, the population growth of the West End continued to swell the ranks of St. Matthews’ congregation. After just a couple of years, they had to contemplate expanding again. This time, though, they would require a much larger site and purchased land at the corner of Livinia Street, now called St. Matthews Avenue, and Maryland Street. Construction on their new home began in late 1912 and lasted for a year.

As for the Ellice Avenue building, in 1914 it became home to Elim Chapel, a non-denominational congregation that was formed in 1910 and had been worshipping in a building at Ellice Avenue at Beverley Street.

Like St. Matthews, Elim soon began to outgrow the space and purchased the vacated former St. Stephen’s Church on Portage Avenue at Spence Street. The final Elim service was held on Ellice Avenue on Oct. 27, 1928.

For the next couple of years, the building was leased by the federal government as the headquarters of the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR), serving as a recruitment office and barracks. This was one of a number of temporary homes before what became known as HMCS Chippawa established a permanent location on Smith Street.

In late 1931, the building reverted to ecclesiastical pursuits when St. Peter’s Evangelical Lutheran Church purchased it. The mainly German speaking congregation was created just a year earlier and had been worshipping in the Good Templar’s Hall on Sargent Avenue. The interior of the church was extensively remodeled before they held their first service on May 17.

St. Peters called the church home for nearly 40 years when, like St. Matthews and Elim Chapel before it, the congregation bid farewell in 1969 for their present, larger church on Walnut Street at Wolseley Avenue.

With the departure of St. Peter’s, the building’s 60-year run as a church came to an end.

The next organization to call the building home was the Portuguese Cultural Centre, which opened on April 3, 1973. It housed a library, space for dance and language classes, and a stage for cultural performances. It became home to the city’s Portuguese Folklorama pavilion.

As the West End’s Portuguese population continued to grow, a new, larger cultural centre was constructed on Notre Dame Avenue, opening in 1987.

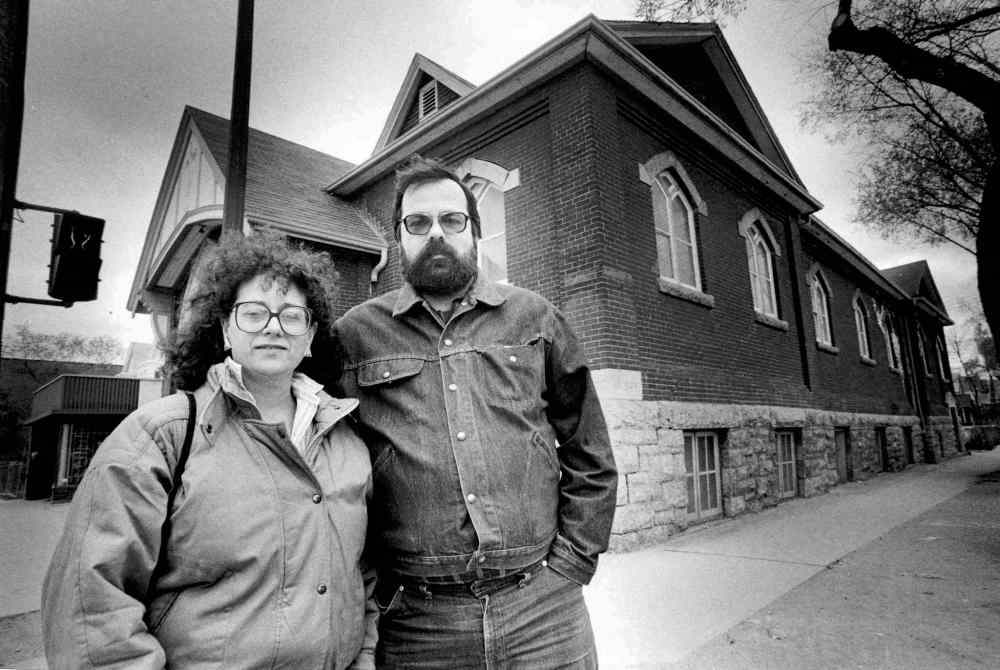

Then along came Mitch Podolak and Ava Kobrinsky who, along with a small army of volunteers, quickly began transforming it into what would become the West End Cultural Centre.

-Christian Cassidy

More recently, it has been acknowledged on a national scale, taking home the Western Canadian Music Award for Venue of the Year six times since 2002, as well as earning the WCMA for Impact in Live Music in 2017 and the Community Excellence Award in 2016 and 2017.

The latter is given to “an artist, group, or music company that demonstrates a commitment to giving back to the community or to charity(s) including contributions to a local neighbourhood initiative, a global cause, or to the broader music community.”

That’s what is also special about the WECC: it’s not just a music venue. It’s also a community hub, and a bastion of volunteerism. The WECC family, while always changing through the years, has been visionary and steadfast in its dedication.

It took vision to open the place, and it took vision to mount 2008’s $4-million capital campaign to transform it into what it is today. Keeping the doors open, the lights on — and the actual walls up — hasn’t been easy. The WECC has been a labour of love for many, many people.

Here is the oral history of one of Winnipeg’s most storied venues, as told by some of the people who built it.

By a shoestring and the skin of their teeth

Before the West End Cultural Centre was an award-winning music venue, it was an idea.

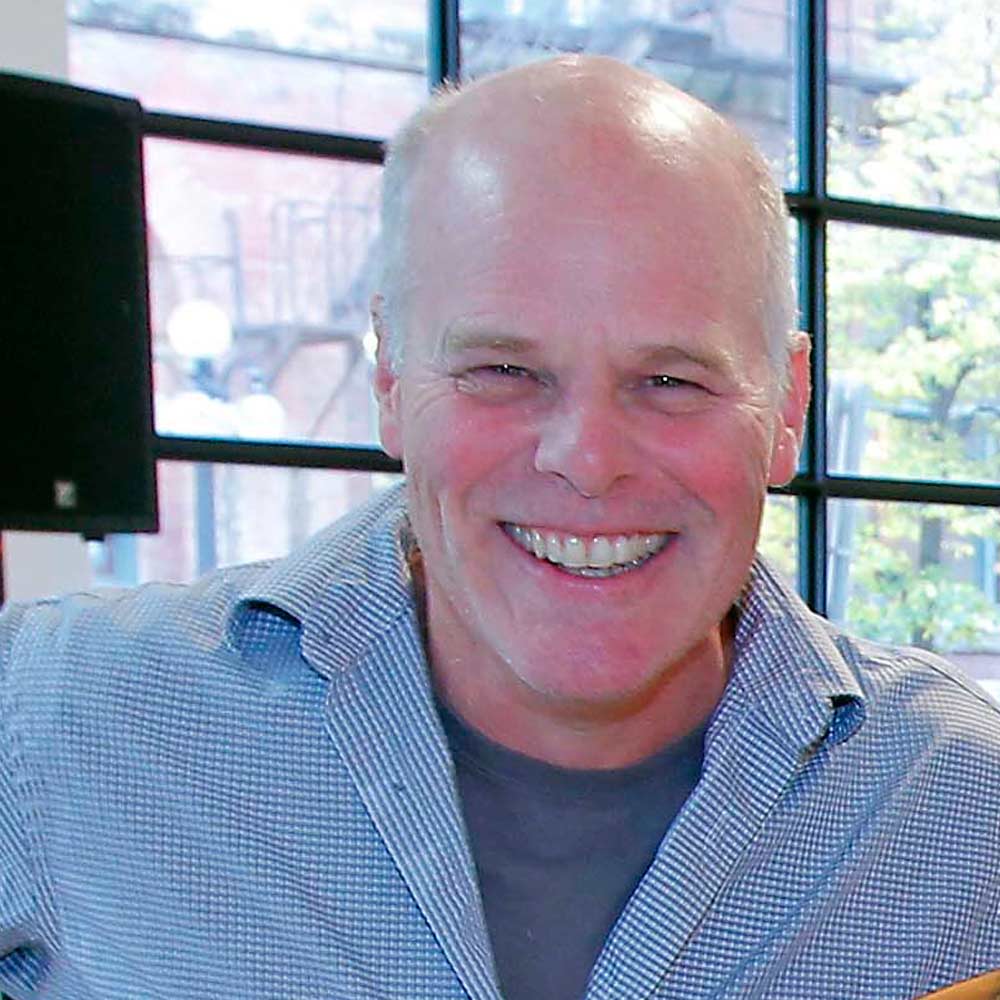

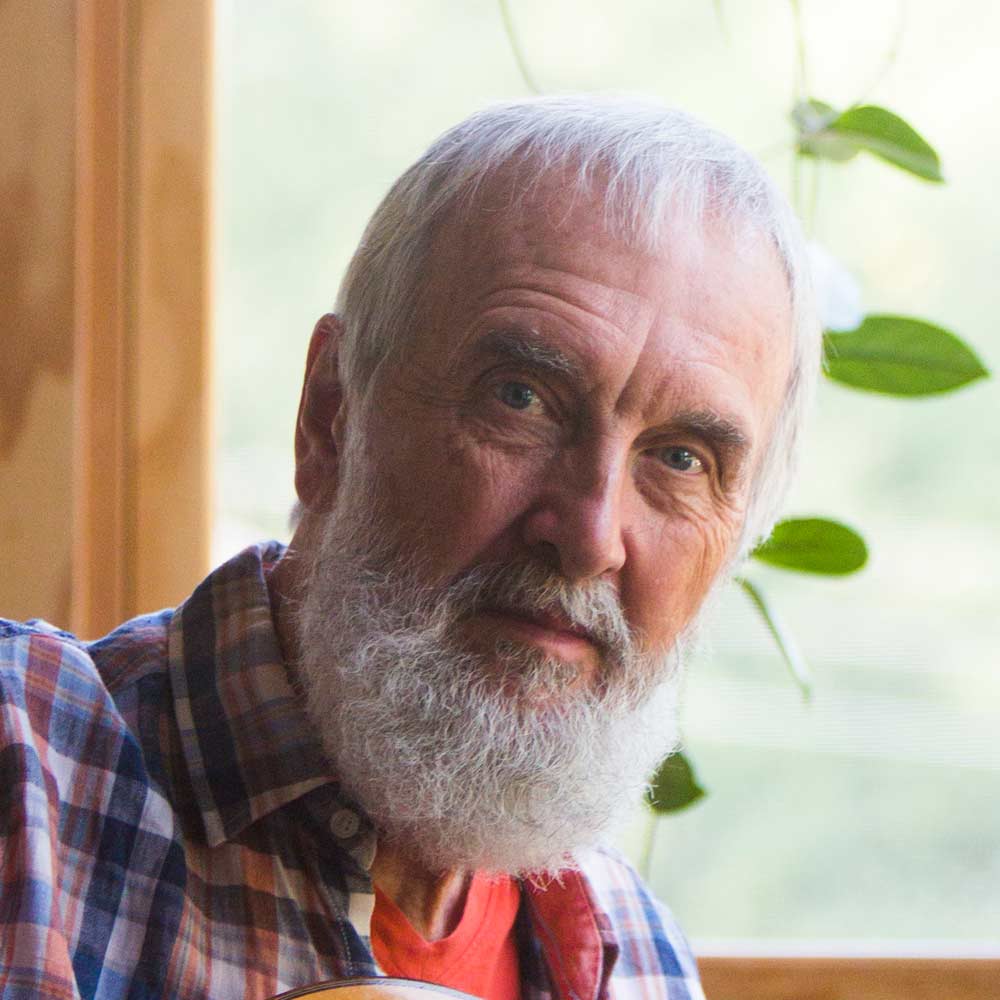

Winnipeg Folk Festival founder Mitch Podolak and his partner Ava Kobrinsky saw the potential in a little building on the corner of Sherbrook Street and Ellice Avenue, and a ragtag crew “who didn’t know what the hell they were doing” helped them turn their vision into a reality.

Ava Kobrinsky (founder/general manager, 1987-1995): As always, (Mitch) Podolak comes up with fabulous ideas and they’re so fabulous that he finds a way to engage so many people to make it happen.

We used to drive by that building, Mitch and I, for years, and he would say, ‘That would make a perfect cultural centre.’

Then a friend of ours, P.K. Nambiar, was, I forget if he worked in the arts branch or which department he worked in the government, he was doing community places, so he knew what was going on all over.

He found out that the Portuguese cultural organization was going to sell the building — it was their cultural centre — and they were selling it to a furniture warehouse company.

So P.K. phoned me and said, ‘Ava, your cultural centre is going to become a furniture warehouse, you better do something.’

We were living in B.C. at the time because Mitch had just left the folk festival, so we started the cultural centre from Tsawwassen, B.C. He wrote the whole paper that convinced Judy Wasylycia-Leis to start it, and it’s called Not By Bread Alone.

We started fooling around with all of this nonsense in January, I think we sent the proposal to Judy in January, and shortly after that I came and bought the building.

Thom Sparling (various roles, 1987-early 2000s): Judy Wasylycia-Leis, who was the minister of culture, gave the organization a $70,000 grant, which was enough to make a down payment on the building.

Ava: We opened the following October; that was fast, to have funding in place and the liquor licence. I worked like a dog. So did everybody else, but they were building. I wasn’t building, I was in the office doing all kind of weird stuff, cutting and pasting newsletters and mailers. The (NDP) government at the time made it happen, without that financial support it wouldn’t have happened.

Mitch Podolak (founder/artistic director, 1987-1992): It was an interesting thing. We weren’t a construction crew, we were just a bunch of people trying to get away with something. We managed to get the walls closed in time for the inspector to come along (laughs).

Up above the stage, Harry (Paine) built a structure that would have held a tank. Harry built the floor structure underneath the floor that existed — the floor collapsed once after I left, they had too many people, and if Harry hadn’t built those structures, people would have died. He saved everybody’s ass without them knowing it.

I said to him, ‘Why are you putting this up for?’ and he said, ‘Ah, there could be too many people here some time.’ Boy, was he smart. Was he ever a smart guy, holy shit.

Tracy Hucul (general manager, 2000-2002): I remember him (Harry) going grocery shopping out on his bicycle to pick up stuff to make for dinner for the artists when they would get in later, and then cooking a really nice meal with the volunteers, and the artists seemed to really appreciate being taken care of that way and being treated like family.

Mitch: Harry Paine, he just died recently… He lived in Toronto and he’d come out here every year for the folk festival for years, and when I started the West End I phoned Harry and said, ‘C’mon, move.’ I knew he was in a particularly low spot in his life in Toronto, so when he was weak was when I got him to come here (laughs).

When he came here it was a great thing because Harry built the West End, and the rest of us, we were just cheap labour through the whole process because none of us knew anything about anything. We knew nothing about drywall. There were a lot of gaps in what we did, but we did pretty good.

Maybe the most interesting part of the founding sociology of the joint is as we were building the place, people would wander by and see what we were doing and one of them was Anton DeGiusti, who became the lighting and sound guy for years. He was hitchhiking through town.

Thom Sparling showed up, all of a sudden he’s a volunteer putting up a wall. That little group of people were the ones to talk about the place before it opened and when we called our first volunteer meeting, 300 people showed up, the place was packed. What a good feeling that was!

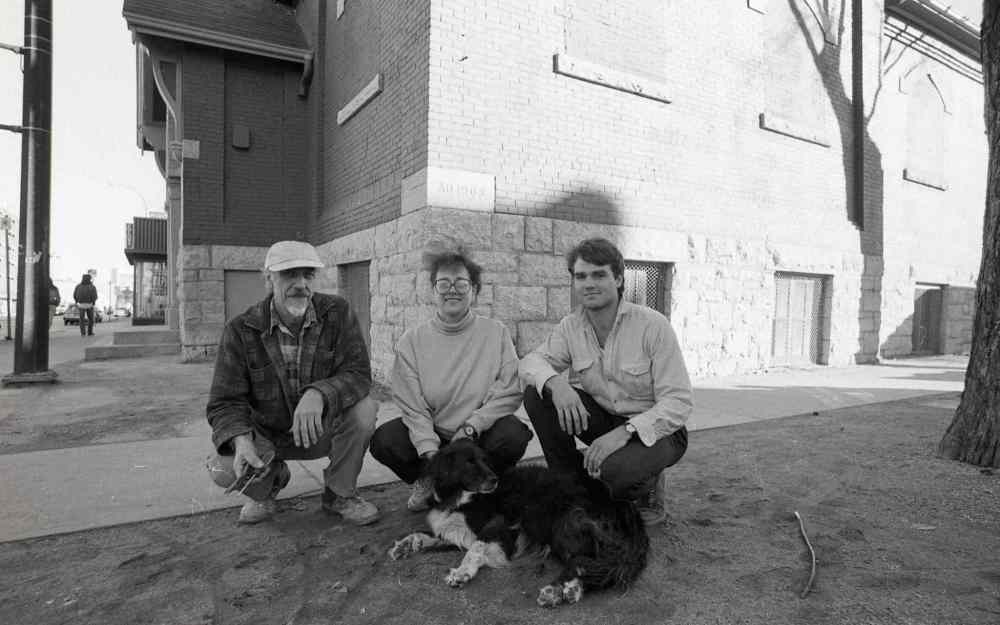

Thom: Getting it open was really interesting because it was a pretty decrepit old building that we gutted. We re-did all the electrical and plumbing and interior drywall. I was still painting the trim in the front hallway as people started to come in for the first show.

We were panicking to get the place completed, but it was amazing because it was a whole community event. Mitch got all these people to volunteer time and energy. So there were all kinds of people who showed up, whether they were teenagers or people working off fines or whatever.

It was manic. It was crazy.

I think we took possession in July and opened in October. It was myself, Craig Skene and Harry Paine who really directed the building of the place.

It was a ton of fun, but there were corners cut, I think, just because we didn’t have any money and we relying on volunteer labour. The money we did have we were using to pay for electrical contractors.

Ava: Opening day was looming and it seemed to me there was a bunch of lumber piled up in the middle of the theatre for a very long time and then all of a sudden it came together… and for many years, I could overhear conversations of volunteers and they would say, ‘I painted that part over there,’ or, ‘I did this,’ or ‘I did that.’

There was real feeling of ownership and sense of belonging and people are very proud of the fact they have been volunteers for a long time or however long. It’s become an important part of people’s lives.

We got a temporary occupancy permit because we booked Spirit of the West for October and the city was very kind and helpful to us — they gave us the permit but we had a bunch of things we had to get done for the 30 shows Mitch booked for November! (laughs)…

So, lo and behold, we just got started in that little basement. We threw out the Coca-Cola containers and rotten beer and got things going.

Mitch: We had chairs borrowed — we didn’t have chairs, they weren’t made yet. You know those red chairs? Those are from the founding, those are 30 years old.

Al Golden used to be a city councillor and a bar owner… I phoned him up and said, ‘I need 300 chairs in four hours,’ and he said, ‘Come and get ‘em.’

We opened up with somebody else’s chairs and the paint still smelling on the walls. Just by the skin of our teeth. And we were sold out the first couple nights, which was great.

Ava: That first night… you know how you say there’s a connection with the artist and the audience? There was no separation at all between the artist and the audience for those two nights.

It was a palpable thing you could feel moving back and forth between the audience and the artist, and everybody was so happy to be there and even the lineup at the bar, you got used to that after a while. It was really something.

Vince Ditrich (drummer, Spirit of the West): We had a pretty awesome house. My recollection of the place is actually being downstairs, there was a song that I didn’t play drums and I went downstairs to grab some water — actually, probably beer — off the rider and the place was jumping so much that the floor above me was bowing and flexing and the doors of all the rooms in the basement were going in and out in time to the music. So, we had ‘em rocking that night.

And I remember seeing Mitch Podolak by the side of the stage and said, ‘Go downstairs and check this out. Are we safe?’ And he came back up and gave me a little thumbs up and went, ‘Nah, we’re good.’

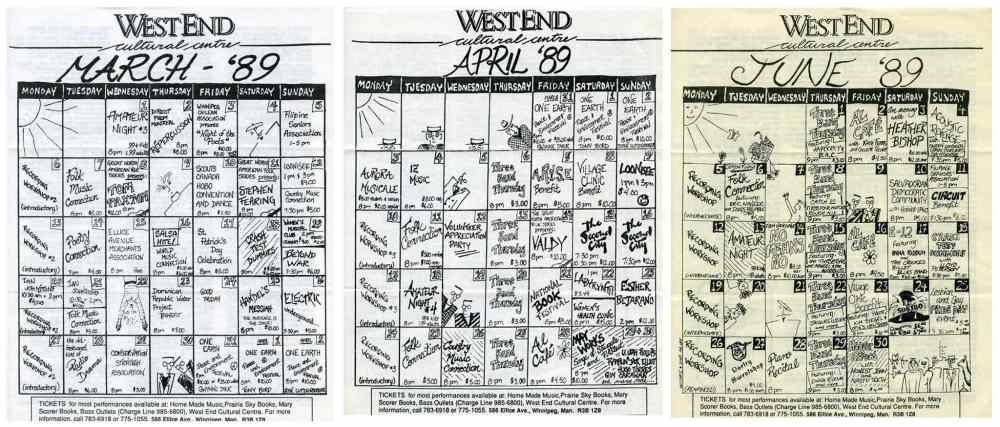

Thom: When we opened, it was sort of this free-for-all. We had Neal Rempel and Bill Spornitz, who were running the Winnipeg International Street Performers Festival — they were in the basement. Every Monday afternoon the Filipino Seniors Association rented the place and came in and did bingo and lunch. Little Filipino grannies used to feed all of us, which was great. Mondays were awesome.

Mitch: Well the first few months, what we did is we programmed pretty hard and we did almost every night. That was a mistake (laughs). We sold out a lot of those shows but we had some empty ones, some great empty ones, which was real sad in some ways. But it kind of established a feel to the place. It was good.

We didn’t know what the hell we were doing, we were making it up as we went along. Who ever heard of a cultural centre that was self-producing? It also could be a rental unit, but largely it was self-produced, and we were really interested in learning how to do that.

And we knew this was needed for the infrastructure, we were pretty damn sure about that, and history has proven us to be right. It’s an important joint in town and I’m really proud of it.

Ava: It was a fun place in a lot of ways, but it was a big struggle because of the funding situation. We were running a building, running a staff, and when the government changed (Gary Filmon’s Progressive Conservatives took power in 1988) they weren’t so friendly to us…

Thom: I think the quote was, ‘I’m not giving that commie one red cent.’ So, for eight years, there was no provincial support. Period. Mitch pissed off all the provincial government people and it was like, ‘No you’re not getting any money.’

So, we had to sell tickets and sell beer and make a go. The place ran on beer sales. There’s no way to put a finer point on it: the bar sales are what kept the place open for the first eight years.

Note: While the ‘commie’ comment above was unattributed, others in the Conservative government were quoted on record. Tory MLA Gilles Roch was once quoted in the Winnipeg Free Press as saying he thought the WECC was a front for communist propaganda.

Mitch: The government changed and we got no support from the second government. We had commitments to have that support and all of a sudden there was a moment of, ‘My god, what are we going to do?’

And we just did it, that’s all. We ignored the realities of that world and we just went and did it. Produced, did our best, tried to build a social base under the place, try to build a community base.

There’s people who just love the place. To me the most important element of it is it’s community base, that’s why it survived any hard times. The hard times always come, there’s never any arts group in the world that doesn’t have them.

Thom: It got to the point where we were the only venue in the city that would allow punk rock to be played. I had a delegation of punk rockers come to me at some point and go, ‘Can we do our shows here?’ and I said, ‘Well, you can do your shows here if you leave the place cleaner than it was when you got here. We can’t afford you to break anything, we can’t afford any trouble.’

I remember John Stewart from Red Fisher got up at the beginning of the next punk rock show and said, ‘OK everybody, we gotta be on our best behaviour or we won’t be allowed back here, and if we’re not allowed back here, there won’t be anywhere for us to play.’

And it was great. We would pack the place. On Saturday night we’d have the folk concerts, but on Friday nights we’d have 400 kids coming in for some really loud punk rock show with five bands. The dichotomy of music genres was phenomenal.

And everybody loved the place. It was a home for punk rock, but it was a home for folk music. It was the best blues jam in the city for a number of years. We even had the Manitoba Chamber Orchestra do performances there for a while. We did everything.

John K. Samson (musician; Propagandhi, The Weatherthans): The first punk show (I attended), my first all-ages show was Red Fisher opening for Gorilla Gorilla, and I was transfixed and changed (laughs).

It sounds silly but it was really important for me. I could see people on stage in a beautiful venue in my home city and see myself being able to do the same thing.

The all-ages punk shows there were extremely important to me. That first show I saw there was the beginning of many. It was the first time I saw Jason Tait play, who I’ve now been playing with for many years…

It’s definitely a building that’s encouraged me as an artist over the years. There weren’t any venues for me to make music when I was young and the West End was dependably open to kids making sometimes horrendous noise in their venue.

Stephen Carroll (general manager, 2014; Weakerthans guitarist): Why I think it’s so seminal for most musicians is because it’s one of the few actual proper venues for a young band to play because of the fact it’s all ages. I remember seeing Gorilla Gorilla, which was a Bif Naked early project. I have distinct memories of that one performance — more, probably, than of any other concert.

(The WECC) gave you an opportunity to grow as a performer, but it also enriched you, perhaps, as a musician because you’d be able to see these kinds of artists without having to sneak into the Albert or the Pyramid with a fake ID.

That venue served as a real community hub for my friends and I growing up in high school. It was a place to play, to see each other, and discover new music.

Thom: I think that was what motivated people to participate and what kept it open: that the vision was, it was about music. At a time when all of the live music clubs in the city — like maybe the Royal Albert allowed original music — but everywhere you had live music in clubs was all about cover bands.

So, to have a venue in Winnipeg at that time that was committed to people coming to watch music — of all kinds, original music — and audiences that were coming to listen to music and not just be in the bar with a band in the background was really transformational in terms of the psyche of both bands and audiences.

Mitch: I remember watching my then 11-year-old son (Leonard)… we came over to the West End and (musical comedy duo) McLean and McLean were on the stage — toilet rock. There used to be this pole by the bar area and Leonard got that spot and he leaned against it and he laughed, he laughed for an hour and a half.

I didn’t watch the show, I watched Leonard laughing. It was one of the neatest experiences I ever had, watching my kid watching a couple dirty old men up on stage.

There were so many nights… watching my own kid play that place since I left, watching Leonard grow up in the West End Cultural Centre. Boy, what a place to grow up.

Overworked and underpaid

The public seemed to be embracing the artist-focused, volunteer-reliant model of the WECC, but those working at the venue every day were exhausted. They were working seven days a week, 12 or more hours a day, and most of the time they, too, were volunteers as the pay was less than stable.

So, by the time the mid-’90s rolled around, many of the originators of the venue decided to take a step away.

Thom: I started to do some number crunching and a preliminary business plan, and it was like, ‘For us to make any money, we have to be open six nights a week, and we have to sell this much beer, we have to bring in this much at the door.’

I don’t know that we were ever busy seven nights a week for extended periods of time but we’d certainly have two-week runs. I’d be there from 11 a.m. to 1 or 2 a.m.

We had a really great relationship with the guy who sold take-out curry across the street. We ate a lot of samosas.

My mom used to phone me at 9 a.m. every morning to wake me up because I was wasting my life, and I got really good at being able to roll over and go, ‘Hi mom, I’m just on my out the door to work, bye,’ and go back to sleep.

When I look back, it’s like, ‘Where did I find the energy?’

Ava: I was so burnt out and tired and exhausted that we moved to B.C. and left my son behind (at 20 years old)… The tension level was always high, trying to keep the place going all the time, it was a lot.

We did not have proper operating support for what was going on, so it was working on cash-flow all the time, but I think by the time I had left we had retired some of the deficit. I don’t remember all the details, but it’s still there.

Mitch: It wasn’t hard to step away. No harder than it was for me to step away from the Winnipeg Folk Festival or the Vancouver Folk Festival or any of the other things I’ve created.

The thing is, if things can’t operate on their own without me, then what the f— good are they? I think it’s very important that the founders of organizations step away from them, to see whether they have a life on their own or not. Founders are weird people… they’re obsessed.

Thom: It was a labour of love. I couldn’t not work at another job or I couldn’t not manage bands and do the things that I did because I never really made a real paycheque for the whole time I worked there.

It’d be like, ‘We did a show and made a bunch of money, here’s a couple hundred bucks,’ sort of deal.

That was one of the first things when I came on as a board member and went, ‘Wait a minute, board members are liable for staff wages. We’re paying everybody.’

So, nine years in, that was the first time there was a formal policy instituted that staff would be paid regularly. The place started under sheer force of will. There was a whole crew of people who came through and put in what they could.

Harry Paine’s premonition

One of the most well-told tales from the West End Cultural Centre involves a Skydiggers show in 1995 at which the dance floor cracked.

Dom Lloyd (artistic director, 2004-2009): Chris Pegis, who was the house manager there for years, apparently it was his first night on the job.

I have a theory about why it collapsed, and my theory is that if everybody who claims they were there when it happened was actually there, then it would have collapsed because there would have been 5,000 people at the place.

But, I mean, that’s part of the lore, too. It’s a storied venue. Talk to Andy from the Skydiggers — he’ll tell you all about it.

Andy Maize (Skydiggers singer): We were on tour with Weeping Tile from Kingston, which was Sarah Harmer’s group at the time. Weeping Tile played their set and we had just started — I think we were about the third song in with our set and we were playing a song, if I remember, it was Just Before the Rain.

Just Before the Rain is an up-tempo kind of shuffle and everybody in the audience was moving up and down at the same time.

It was kind of fantastic to look at and, the next thing I know, I’m singing one of the verses of the song and Cam Giroux, who’s the drummer in Weeping Tile, was suddenly right beside me… I thought, ‘Wow, things are going really well if Cam felt he had to jump up on stage with us, this is great!’

But he’s trying to get my attention and grabs my elbow and says, ‘Andy the floor is collapsing.’

They were downstairs in the dressing room which, at that time, was right under where the front of the stage is, and so the floor was supported by these big beams and they were sitting down in the dressing room and one of the big beams cracked. Cam said it was like a gunshot.

So he came up on stage and we had to stop. We stopped playing because the floor was literally in danger of collapsing.

We got people to move back and we encouraged them to dance less aggressively — I think at the time I called it ‘sexy dancing’ — and we went on another couple songs and at that point the folks in charge of the venue made the decision it was too dangerous to continue, the potential of the floor fully collapsing was too great.

I do remember the show was off to a great start, though.

Less money, mo’ problems

In the late ‘90s, the West End Cultural Centre fell on hard times financially. While there weren’t too many people willing to discuss the extent of the debt, it accumulated in large part due to an audit by Canada Revenue Agency.

The general manager at the time, Katarina Kupca, respectfully declined to participate in this story, and then artistic-director Tremaine Burrows did not return a request for interview. The turn of the century brought in a period of renewal — both organizationally and artistically.

Chris Frayer: (artistic director, 2000-2003): (My time at the WECC) actually felt pretty long, to be honest. It felt longer than four years. We were really rebuilding. We were rebuilding financially, we were rebuilding our administrative systems, and we were reinvigorating the venue artistically. It was a time of transition, so it was a good time to give it a shot in the arm.

Tracy: It was just a couple of years, it was short but it felt like a very transitional time for us.

Chris: I quickly outgrew the size of the room, so we did a lot of out-of-venue productions. We became a production company. That meant engaging the volunteers more outside of the venue. It meant using Le Rendezvous a lot.

There was one night we had AFI at the Convention Centre, we had Garnet Rogers at the West End and Hawksley Workman at the Burt. In one night.

Doing a lot of things outside the venue helped out bottom line. It was an interesting time.

A lot of the shows we did do there were shows that didn’t happen anywhere else in Canada. For example, I did a lot of the Fat Possum blues stuff there at the time. We’d literally fly in the musicians from Oxford, Mississippi to play.

I felt like we needed to have those really special shows no one else was getting. I also got sick of driving to Minneapolis. I wanted to bring music to us instead of us having to go to music.

Tracy: It was a very exciting time musically with Chris Frayer as the artistic director and a difficult time operationally.

So there were lots of great shows that were happening, we were really bustling, but our finances were strained and we were concerned about the building as well, and the integrity of the west wall.

So we got an opinion from a structural engineer and obviously the resulting news was what lead to the beginning of the journey to the new building.

Thom: The west wall on Sherbrook was collapsing. The building inspectors came in and said, ‘We’re going to shut you down if you don’t do something about this.’

We shut down and built a two-by-six wall to support the roof because the exterior wall had become compromised. It was Kat (Kupca, former general manager) who I have to give credit to for raising the $70,000 or something like that to rebuild that wall and strengthen the foundation.

Tracy: My primary goal was to help stabilize operations and to try to get us back on track so we could keep doing what we were good at, which was being an intimate musical and community space.

We had just underwent a CRA audit, so we were dealing with the outcome of that. And some of the things that I did to help us start working our way through that was working with our board and our partners to develop a plan to get us back in the black.

I converted positions at the centre from contract to payroll positions, which meant regular CPP and EI and all the fun stuff (laughs). And, you know, making sure we were doing our regular Revenue Canada submissions, developed job descriptions, started looking for additional grant funding.

… We had hired a couple of new positions, an office co-ordinator and a community co-ordinator, because it became apparent we needed more boots on the ground to get done what we wanted to be doing, and that was through a federal jobs program.

The wicked wall of the west

The West End, which was originally built in the early 1900s, was starting to show its age. The wall facing Sherbrook Street was collapsing and the temporary wall erected to support the roof was only a stop-gap for a serious structural problem.

A decision had to be made: move, shut down or rebuild.

Nan Colledge: (general manager, 2002-2009): The two projects I knew I would be taking on were to get community programming started, which had always been a dream that had so little opportunity to do it, and to get out of our financial hole, because there was a big financial crisis before I got there.

So I knew I had to dig us out of a financial hole, but I didn’t know I’d have to dig us out of a literal hole as well.

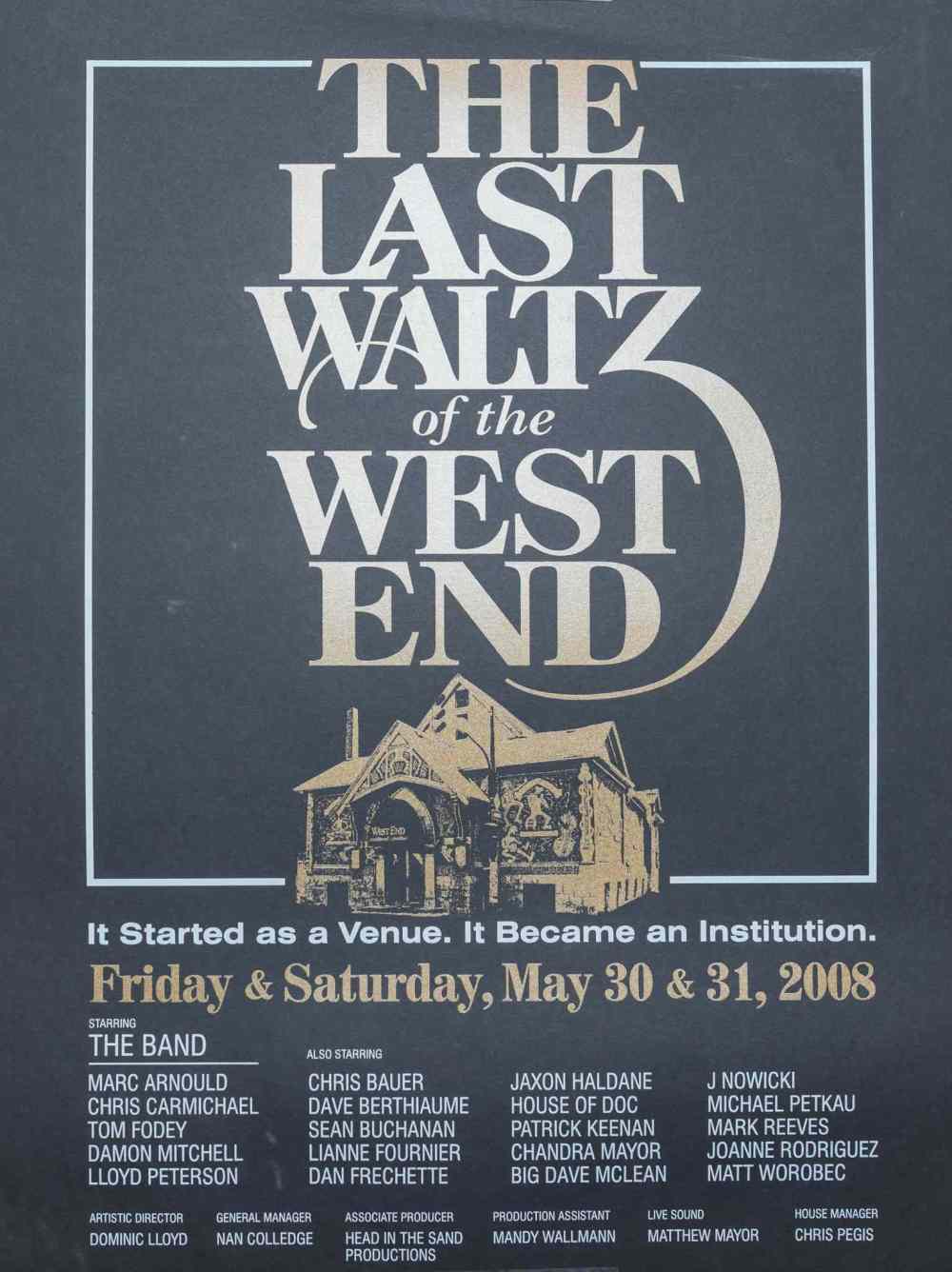

Dom: I was the AD through that period, including the year we were closed down and had to host shows in other venues.

It was a great room and it was a place that everyone loved — but it had a lot of issues. From lack of access to people with mobility issues to no wing space, no storage space — and, on top of it all, the wall was falling down.

We used to measure it on a semi-regular basis. We used to climb this ladder on Sherbrook Street, and there was a bunch of marks on the top of the wall in Sharpie. We’d climb this great ladder in the middle of the day and, like, measure how far the marks had moved.

Nan: The building was in very bad shape when I got there, which we all knew about, and the main problem was that the west wall was collapsing, so we were monitoring it all the time and constantly under threat of being kicked out.

So we knew we had to fix the wall and that was going to cost about $100,000 which, for a shoestring operation, we were going, ‘How on earth are we going to find that?!’

And then it morphed into a $4-million capital campaign. We decided rather than just try to fix it, why not just try to go big and see if we could create the most environmentally sustainable performing arts centre in Western Canada on that corner. And that if we went big, you could always climb down from there, but nobody would get excited about fixing a wall.

But people did get excited about us wanting to stay in that neighbourhood, to really be able to expand our community programming, which was kind of wedged into odd corners — like drumming lessons outside my office door, which was… a challenge (laughs).

And the environmental side of it caught a lot of people’s imagination. And we had really wonderful support; private sector and public sector, a lot of people got the vision and got on board and it took a long time, it took us five years to do it, but we got there and I still kind of wonder how we did.

It was fundraising, designing, having a fit at the costs, redesigning, more fundraising, so it was primarily trying to get ducks in a row and money in place.

And then the construction took about year (in 2008). We were out for almost a year.

Dom: We had no home for a year. We had to continue programming. We did shows at the Pyramid, we did shows at the Park Theatre.

If you ask Erick at the Park Theatre, I’m sure he’ll tell you that we were the ones who brought music programming into that place regularly, and now it’s a real cornerstone of the music community — local and touring.

We did shows at Crescent Fort Rouge, we did a show at the Albert. We were all over the map.

The amount of programming we did that year isn’t what we’d normally do, but we certainly did a lot.

Erick Casselman: (Park Theatre owner): It’s true, we had only done a few shows prior to that, but the two main instrumental events were the WECC shutting down for that year for renos and me being able to pick Dom’s brain like crazy, and JP Hoe recording the Live Beta Project here.

The West End Cultural Centre helped take live music from the community halls and backrooms of Winnipeg and gave it a real stage to showcase itself.

Without it, there would not be a Park Theatre or many other Winnipeg live music venues.

Meg McGimpsey (general manager, 2009-2013): At one time it was sort of thought, ‘Can we run community outreach programming if don’t have a facility?’ What we ended up doing was mostly going directly to the schools.

Much like the concert programming, it presented this really interesting outcome that I don’t think any of us were anticipating in that we ended up reaching out and making new connections with our community — whether it was other venues or school groups because we were no longer using our facility as home base.

When we moved back into the room, we had even more connections in the community and a space that would allow us to bolster our programming.

Nan: We did a lot of consulting with people in the community, our volunteers, our audience members to find out what was important to people. And what was important to all of us was keeping that cozy feel and trying to save the building, which we did, and I’m so glad we did.

It probably would have been easier to just knock it down and build a box, but it just would have no character. It felt like it kept its soul.

Dom: We worked with a really great team — musicians and people from the community and all sorts of different people to figure out what was needed and how we could do it.

We came up with this fantastical design. My impression of it was that there was a tremendous building boom going on in the city, so between the time we started figuring out what a $4-million building could look like and when we finished designing the $4-million building, it was no longer four million bucks. So we went back to the architects and they redesigned it.

So the rebuild wasn’t exactly what we’d hoped and dreamed, but it was certainly done in a way that made it a better place and did it in the most fiscally responsible way possible.

Meg: The building has its LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) silver designation — the first venue in Canada to have that designation that we could find.

Which is also a testament to the organization. They put their money where their mouth is.

The organization has always kept the ethos of the WECC at its heart, and I really appreciate that about the organization. They try really hard to meet the values that it espoused.

Nan: There are things like geothermal heat, a ton of recycled material, a lot of the flooring is from old elm.

There was a courthouse in Calgary that was being torn down, a new courthouse so it was crazy, and our construction manager went out there and managed to get hold of all the doors, a whole load of glass and windows.

The stairs in the upstairs balcony bit, they came from the old Epic Theatre on Main Street. And CentreVenture were really helpful; in the changeover, before the Epic was knocked down, they owned it for something like half a day and said, ‘OK, during the time we own it, you can come in and harvest anything you want.’

So we went in with a whole team and took chairs and took marble. So there’s lots of really neat things that went into the building and it was lovely to give them a second life, as well as cutting down some of the costs.

Fred Penner (musician): What some people may not know is the floor in the boardroom is made out of elm trees (lost to) Dutch elm disease. All these trees had been cut down and you cannot burn them because that releases the spores into the air. So all these beautiful elm trees were being held and ultimately cut into planks that makes the floor of the boardroom.

Also in the washrooms when they were creating the sinks, the product they poured to make the sinks was made of old toilets, old porcelain, glass bottles, wine bottles, beer bottles, ground up into small enough pieces to mix with the hardening substance and then they poured the sinks in the bathrooms. You can see it. It’s such a beautiful recycling of material.

Meg: There were obviously challenges, but I think back to when we were reopening the facility. It opened at the end of May (2009), and the two weeks leading up to that, we had all our chairs in storage and they were dusty and needed to be cleaned.

So, you would work your eight hour day in the office, and then you’d go to the parking lot and pull out chairs and clean them.

On the week we opened, they were still putting some of the finishing touches on the inside of the hall. So, the bands would be sound checking and staff were tearing down scaffolding and doing sweeps to make sure there wasn’t a hammer lying around somewhere.

The amount of work the volunteers did — like running the cabling for phones and internet — that was all done by volunteers.

The work that people have put into that place is incredible. I know it sounds like I’m giving you a cheap sound bite, but I sincerely mean it.

Nan: We had an opening night reception for our donors, our first concert was for our volunteers and then we had a week of concerts.

And it was lovely because I think people were… we were all fond of the place in its quirky way, but there was lots of stuff that did not begin to meet code, and having the washrooms next to the stage was kind of weird.

So it needed to be done, but we didn’t want to create a really startling, modern box. We wanted to make the new concert hall feel that same cozy feeling.

And I would see people walking in that first week, I was up on the balcony, and they would walk into that big lobby area and I could hear them go, ‘Oooh, I’m not sure about this,’ and then they’d walk into the concert hall and just go, ‘Ahhh.’ It felt like home.

So many performers said it’s so nice to be back in this hall, but I would think, ‘You’ve never been in this hall! It’s a new building,’ but you don’t realize it because it feels just like the old one, just without the washrooms by the stage.

It gave me a lot of sleepless nights, but no regrets.

Dom: (The re-opening) was awesome. I don’t even know how you describe it. Everybody was behind it. And peeking in over the course of that winter, like, ‘Oh my God they put a balcony up, this is amazing,’ and there’s no roof on it and the snow’s all piled up in what is now the hall.

But, man, I certainly do remember that moment when we reopened — we had Greg MacPherson and Hawksley Workman to reopen it — I will proudly say I remember walking out onto the stage and saying, ‘We did it.’ And the crowd just cheered.

Hawksley walked into the room and said, ‘I thought you rebuilt it? It looks exactly the same.’ And it does — the bathrooms notwithstanding, and the fact that (the stage is) 100 feet to the south of where it once was.

Thom: I just remember Mitch railing at me, ‘They’re gonna wreck it! They’re gonna wreck it! They’re gonna wreck it!”

I remember Danny Michel (who performed during the grand reopening week) onstage going, ‘This is really crazy, I can’t tell I’m in a new building. They’ve done an amazing job capturing the essence of the old building. The only difference is, there’s no buzz in the sound system.’

It was really great. When I think back to what we went through in the first 10, 12 years to get the place open and keep it open until it had enough reputation and organizational structure in place that Nan was able to do the capital campaign and build it, it was really remarkable. It really needed it.

Meg: The staff going through the transition — we had a really strong team of staff and we had a really strong team of staff after we were in the new facility, too. The place has really called people with a tremendous amount of talent and passion and intelligence.

But we were tired. We’d been sprinting through a marathon for several years. I think we all wanted to take a moment to take a deep breath, but you get into a new facility you realize, ‘Oh no, we still have to sprint.’

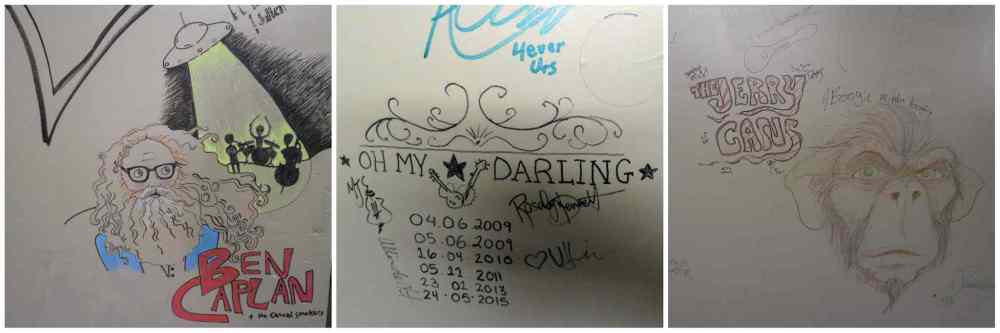

The great mural debate

A mural was painted on the outside of the WECC in 1990 by artist Larry Spittle featuring a colourful crew of figures playing musical instruments. It became part of the visual iconography of the neighbourhood.

The decision to replace it with a new art installation after the renovation was, to quote then-artistic director Mike Falk, “a bit of a to-do.”

Nan: A couple of people were sad about that and in some ways we were sad, but I had heard a few complaints over the years about the murals and some had said they were racist.

I thought, ‘Hmm, you know, that hadn’t occurred to me, maybe there is an issue there.’

You know, they had their day and I was happy with being able to do a new art project to replace that, so that there was still something exciting there.

Ava: Here’s a story about the murals: Rosalie Goldstein, she showed up in 1977 when the folk fest was in financial trouble and helped us raise a bunch of money and eventually became artistic director.

Well, we came back and they were doing whatever they were doing with the West End, and I was explaining to Rosalie, possibly in a vehement manner, that I was upset they painted over the mural that the people of Manitoba paid for and that Larry Spittle had painted (in 1990), and she said, ‘Ava, you have to let it go, just relax.’

And then we drove by and saw it was painted over and saw what was there and she didn’t like it very much and she started to get as vehement as I had been.

So I told her, ‘Rosalie you have to let it go,’ and that was that.

The WECC 2.0

Although the walls were no longer crumbling down around them, the West End staff were dealing with shifts within the music industry.

In recent years, the roles of general manager and artistic director attracted some high-profile people from Winnipeg’s music scene, including: Jack Jonasson, who managed the Lo Pub and played in Novillero and the Paperbacks; former Weakerthans guitarist Stephen Carroll, who is now the manager of music programs at Manitoba Film & Music, and Mike Falk, who is now the artistic director of the Winnipeg International Jazz Festival and founder of the local label Head in the Sand.

Jason Hooper (artistic director, 2011-present): It was a little bit upbeat when I started, because it always is with change.

I’m not sure there were too many issues at the time that were any different from any not-for-profit or music venue.

The industry was changing then and we’re still going through the changes.

Jack Jonasson (general manager, 2014-present): I come from the music venue side and the musician side and not so much from the not-for-profit side, so that’s been a steep learning curve.

When I came in, there had been a gap between general managers, so there was a couple of months in between — and I’ve gotten lots of help from previous GMs— but there wasn’t a direct transition.

The board (and staff) was helpful, but there were a lot of things I had to figure out. But I like that, I like a challenge.

Mike Falk (artistic director, 2010-2011): Obviously, you have to keep the doors open, which means selling tickets and selling booze.

Every now and then you book a show that maybe artistically you’re not quite as keen on but you do it to help pay the bills. Every artistic director for every non-profit and even for-profit organizations have to book shows to pay bills, too. You’re not going to be in love with 100 per cent of what you book. And that applies to the festivals, too.

That’s the nature of the music industry — trying to stay alive, keep everyone engaged and employed, and keep the audiences coming.

Even while the West End is a not-for-profit, it’s still an entity within the music industry. And the music industry is very much a business, and a very competitive one. You’re navigating artists and agents and labels and local competitors as a business person, within the framework of a non-profit arts centre.

Jason: I wanted to be a little more accessible for local artists and local bands, to create a more welcoming space for them, which brings in a little bit more risk.

But my previous job was here as community programming, so it kind of felt like there was this gap between the cultural centre and the community that happened around the time of the renovation and I think mostly that was just from being closed.

So I wanted to fill that up, close that gap up, and put us back in people’s minds as the first place they want to do their album launches.

Mike: I wanted to present artists on that stage who might not play that room otherwise or come to Winnipeg otherwise. I tried really hard to bring in people that were outside the original scope of the venue.

Because it’s a listening room, I wanted to present quiet music that can impact deeply. You’re only going to sell 50 tickets for that show, but it’s still going to be better for the audience and the artist to have them play there than to have that show at a loud rock club where the artist has to play into the noise. I was keen to make sure that if someone was a listening artist, we could give them a show that would be valuable to them.

Often on those kinds of shows, especially developing artists, you’re not making money on those shows — you’re losing money on those shows — but it’s part of the West End’s investment in the music community.

Dom: A perfect example is Feist. I can tell you exactly how many people were there on June 15, 2004 — there were 56 paid and 96 comped. And that was one of the first shows I had booked.

It was before Let it Die (Feist’s 2004 sophomore record) came out, and we put it on and no one bought tickets. It was like, ‘Come on you guys, she’s gonna be a big deal.’

Then she won a Juno and never played the West End again because she got too huge.

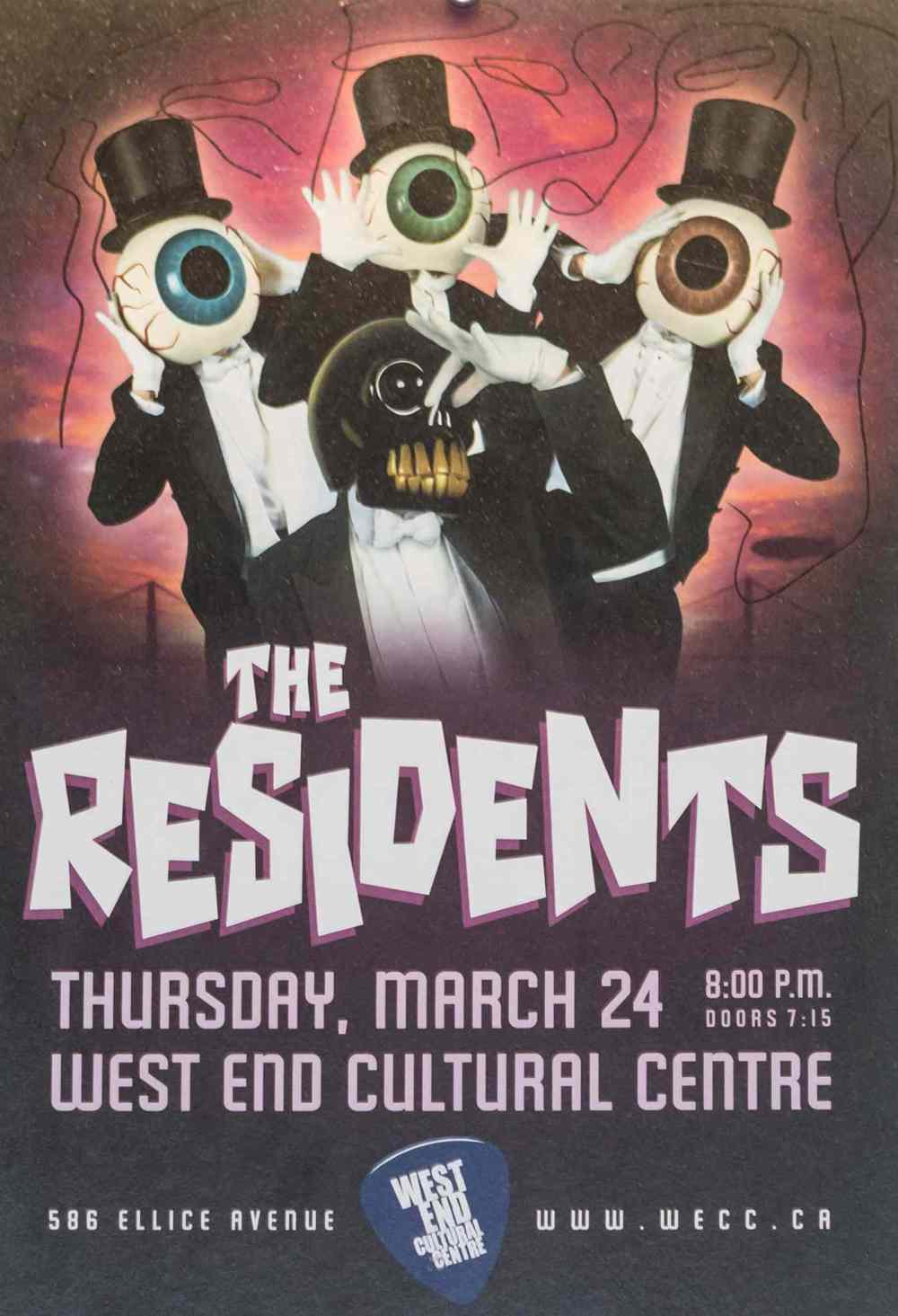

Mike: The Residents show we pulled off: we totally botched the announcement and let it slip onto Ticketmaster before it was supposed to, and all of a sudden we sold 75 tickets without the show being on sale. I was like ‘Oh no, what have we done? What if the agent pulls the show?’ But it worked out.

We put it on sale for real, it sold out in heartbeat and it was really beautiful. That’s one of those bands you get to see once in a lifetime.

We had to, like, find a fireplace for them. Their rider had a fireplace on it. And I think Jason tracked down this decorative fireplace in some industrial building. We went and picked it up and brought it on stage for the Residents and they were like, ‘What!? No one ever gets the fireplace!’

That fireplace is at the West End still to this day.

Stephen: Some days, the show ends and things go sideways. Evan Dando was there, legend from the Lemonheads. He loaded his stuff into his car and came back in to settle and in the 10 minutes it took to settle, someone stole his guitar and cello from his car from the back lot — which was brutal because it was a heritage Gibson and it happened so quickly.

I found myself the next day on Kijiji trying to locate this guitar. He needed it, he was emotionally attached to it, we felt terrible.

I found myself walking around with Kelly (Leschasin, former WECC communications person) to all the pawn shops in the neighbourhood like a couple detectives on the case, asking people if they’d seen anything. We did get it back, through a miracle of Kijiji.

The cello — never been located. So, if anyone sees a cello in a black case with flames on it, that’s Evan Dando’s cellist’s.

Jason: I came in the year before the 25th anniversary and am kind of surprised to still be here for the 30th. It’s a really tough job sometimes. It’s really hard, it’s really draining, very stressful.

In some ways it’s kind of like a hockey coach in that sometimes you’re hired to be fired. It’s incredibly rewarding, but sometimes when I look back, because it is my sixth anniversary… it’s a little amazing.

Jack: We had already started talking about the 30th when I started here (in 2014). One of the first things I did was hire a new marketing person… and so we had already started talking about the 30th and I started thinking about the rebrand.

It hadn’t been done since the renovation in 2008 and there are ghosts of old logos and marketing directions that have made their way through the years and so the rebrand is the big project that I had seen coming down the pipe.

And now we’re doing it — we just put out a new logo and are working on a new website and we have merch for the first time since I’ve been here. The logo and rebrand was all done by Roberta Landreth.

We presented a questionnaire for the rebrand and a lot of it is about feelings and what kind of message do you want to convey and we kept coming back to that (renown Inuit throat singer) Tanya Tagaq show (March 18, 2017). There was something really transformative about that night, it was like she was tapping into something otherworldly, on a different plane of existence and pulling it down into the room for all of us to experience collectively.

That’s what we strive for every night. We know that music is a life-changing force; all of us that work here, all the people that come to shows here, are people that love music.

They know the effect that music has on your soul. So that message really permeates everything we do.

Jason: There’s moments of transcendence, which is a big word to use, but I experienced it and I know a great many people experienced it with Tanya Tagaq.

And I don’t know that you can experience that in a bigger room or a different kind of room, so I think that’s part of it.

When you have that moment, whether it’s surprise or transcendence, that creates a bond in your memory and in your experience that makes people feel like this is a second home or a place where you can go and know you could have this very incredible moment at any time.

The most magical place on earth

The WECC means many different things to many different people.

For some, it’s a place to see a once-in-a-lifetime concert, but for others, the connection goes beyond the artist onstage.

Mitch: I think it’s the social base. I think the West End and the Winnipeg Folk Festival and the Vancouver Folk Festival and a whole bunch of other things across the country are built with a technique that is based upon volunteerism.

The thing about volunteers is they are also your PR. They’re your word of mouth in the community, and word of mouth, in terms of giving anything longevity or giving a thing a life, the word of mouth and your social base is the most powerful tool you need… It’s bloody wonderful.

It’s not the geniuses who run the place, it’s the energy provided by everybody else.

Dom: People really like the fact it’s a volunteer-driven organization. The people who are selling merch, and the people who are tending bar, and the people who are taking tickets are all volunteers, so it has that community feel to it.

It’s also an artist-driven organization, too. It puts the artist first. It treats artists well and, in return, artists provide the best show they can.

The shows are always great. Everyone’s got a story about it.

Mike: (The volunteerism) is really powerful. Every day, every show, a bunch of people show up to give a few hours of their time. It’s a little mind-blowing.

It really expanded my view of the graciousness of the people in Winnipeg’s music community who do that. They do that for the West End, they do that for the Folk Festival and the Jazz Festival and Fringe — they give so much time to our arts events and cultural institutions. It’s really amazing.

Jack: Volunteers are the backbone of the WECC. This place wouldn’t operate without a strong committed dedicated core of volunteers that buy into the mission and vision of the West End Cultural Centre, a place that is a community not just for music.

“There’s a sweetness to the WECC because of the volunteers. It’s so community oriented and they want people to have a great experience. That’s one of the core values of the WECC, whether it’s written down or not.”–Stephen Carroll

Stephen: That was one of the highlights, to sit down with the volunteers after a show. They’d have their pizza and soak up the vibe and tell their stories of the night and kind of their own rejuvenated energy from the experience.

There’s a sweetness to the WECC because of the volunteers. It’s so community oriented and they want people to have a great experience. That’s one of the core values of the WECC, whether it’s written down or not.

Thom: There used to be a lot of networks of people before social media. With social media, a lot of that interpersonal connection seemed to get subsumed by social media and people’s fascination with that. But there’s still a need for people to come together and share a common experience.

I don’t think the West End is ever going to diminish in its place. It’s that whole connection of people, and music is what draws them to it.

Fred: It has its foundation within the community, that sense of community is so vital, it’s so important because as the technologies seem to increase, people are spending more time at home that making the effort to buy a ticket and leave your home and go through finding parking to go into a common place with 400 other people to share in the performance of music by these talented human beings is almost becoming unique in its simplicity. But really a vitally important balance to the insanity of the technology that has taken over.

Tracy: I think the intimate space and the way the hall was developed makes everybody feel like they’re part of something special when they’re in the room. I think people are more connected to the artists. The sound and the views are great and you can feel a notable energy in the room when you’re in there.

Mike: I think because you can tell throughout its history that people care. They care about music. They think about how it will sound. They think about sightlines. They think about the stage and how it will feel to performers and the audience.

The experience for both artist and audience inside that hall has always been something a lot of care has gone into.

It wasn’t a place to cram a bunch of people in and have a sweaty show and make a bunch of money on the bar. It was about creating memorable experiences for people.

“Even if people don’t know all the nuances of the story, they recognize that there’s a small little arts organization that, even in the face of great adversity, said, ‘We can absolutely do this,’ and did it.”–Meg McGimpsey

Meg: I think it’s because it’s the Little Venue That Could. It was this little community venue, this old church one-room space that brought people in and had a really folksy, community-oriented feel to it.

I remember there would be work weekends for volunteers and we would go in and help paint the inside of the theatre. How else can you build a sense of ownership for a place than to have people actually get their hands dirty and help keep the place running?

Volunteers used to make full meals for artists. It was those kinds of activities that built community.

As the organization has grown and strengthened, it’s done a really great job at keeping that — everybody rolls up their sleeves and pitches in to move the organization forward.

It also accomplished this tremendous thing. It’s no small feat for an organization of that size to have fundraised a campaign of that size, to build a new building, and then come out of it debt free and ready to take on new challenges and new programming.

I just think even if people don’t know all the nuances of the story, they recognize that there’s a small little arts organization that, even in the face of great adversity, said, ‘We can absolutely do this,’ and did it.

I will not say that at every point in time we were sure that we’d be able to complete that renovation on time, or on budget, or at all, but all those things happened.

Chris: If people think it’s just a bar, then they aren’t familiar with what the West End does as an organization.

It’s not unfair that they get help to do the things they do because they do things that are just a break-even return for the organization but have huge gains in terms of community impact. And it is a beacon. Any musician who has ever played there will tell you. It’s a cornerstone of the West End.

“It’s had a couple generations of people who just love the place and do good work. It is alive… it’s exactly what it should be.”–Mitch Podoluk

Vince (Spirit of the West drummer): It exists because it’s in Winnipeg. That is not going to exist anywhere else. Winnipeg’s sorta the last bastion of the old-fashioned middle-class city where people have carports and basements for the boys… It became a big city and an important one, but it’s the only one of its kind left and so the cultural interest and drive of a population of that particular variety are reflected well by the West End.

It’s not high-falutin’, but it’s hard working and foresightful and it’s a good embryonic location for people to be loved and taken care of through their middle years before they burst into the greater-sized venues. And the whole mentality surrounding that is one of nurturing, and it’s a throwback to the old folk tradition when people really, really paid attention to the artist and what they had to say.

Ava: I’m so happy that the West End is there and it’s still a place to showcase new artists. We always tried to have an opening act with so-called name acts to expose them and bring people together, and as far as I know it’s still happening.

Mitch: I love the fact that the West End is up and running and it went through such a hard time to start. It’s had a couple generations of people who just love the place and do good work. After we left, the place was alive. It is alive… it’s exactly what it should be.

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, October 28, 2017 9:26 AM CDT: Typo fixed.