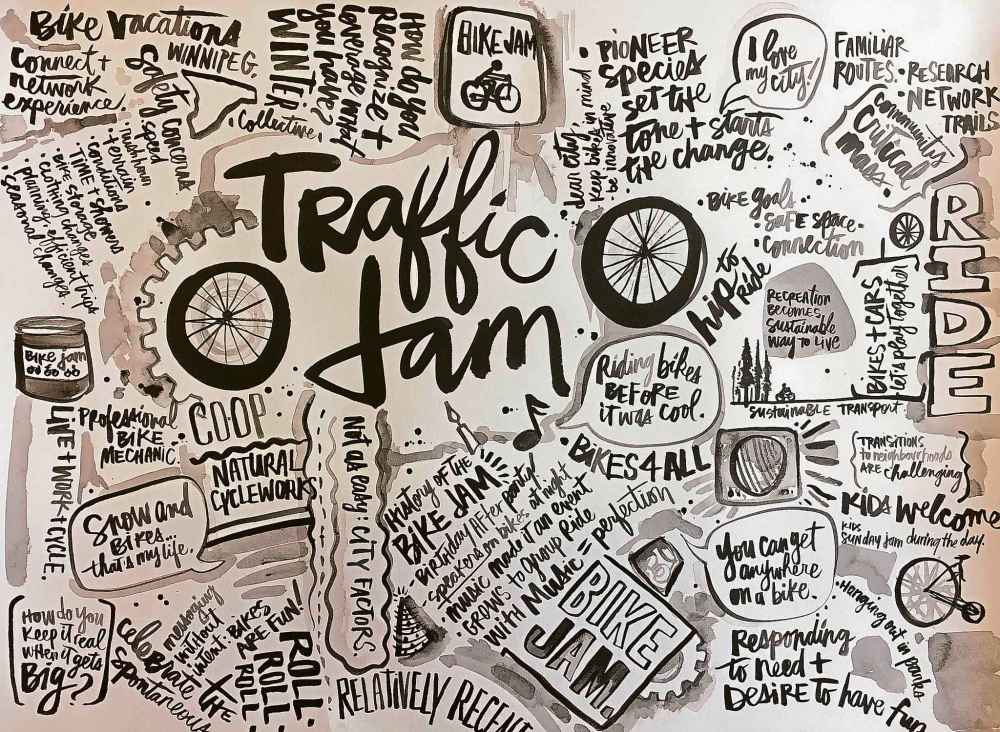

Traffic jam

Cycle advocacy transforms Winnipeg streets

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/07/2017 (3072 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It all started at a birthday party when three friends decided the evening’s festivities would continue into the early morning. With speakers fastened to their backpacks, Will Belford and his friends explored some of their favourite neighbourhoods – stumbling upon new ones along the way. Over time, this cycle celebration has evolved into what is now known as the Bike Jam, a monthly group bicycle ride led through the streets of Winnipeg, augmenting the city around them with music and celebration.

HTFC Planning & Design’s Elly Bonny and Jim Thomas sat down with Belford to explore the impact Bike Jam has had on the city — as a quick, cheap, and do-it-yourself tool to affect and change urban space. Natalie Bell, a recent Bike Jam participant, joined in on the conversation, offering insight on how this initiative has influenced her own perspectives about cycling.

Born and raised in Winnipeg, Belford attributes Natural Cycle, a bicycle repair shop he manages in the Exchange District, as a motivating factor in his desire to improve a community’s economic, social and cultural conditions.

“Natural Cycle is a worker co-op and this factors into my perception and how I view the world, and how I interact with it. I’m all about people coming together to make positive changes for themselves and others,” he said.

Thomas, native to southern Ontario, moved to Winnipeg for school in 1979 and never left. A Fellow of the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects, Thomas has been a practising landscape architect and planner for 35 years, and has recently transitioned to a new role at HTFC as a senior advisor. In between planning and designing communities, parks and regions, Thomas trains for races like Breck Epic, a six-day mountain bike race through Colorado’s back country. In addition to racing, Jim is an enthusiast of cycling holidays and uses his bike as a prime mode of transport in the city: “I have used my bike as a mode of transportation for years, since primary school. It was really uncool to ride bicycles when I was in high school, but of course now, cycling is very hip.”

Bonny, on the other hand, realized cycling could be routine after studying abroad in Kenya. Her classmates established The Otesha Project, a non-profit organization that employed experiential learning, theatre and bicycle tours as opportunities to empower Canadians to take action on sustainability and social justice issues. Bonny took part in the Otesha project’s first trip in 2003 and found herself cycling across Canada promoting sustainability: “It got me into the attitude that you can get around anywhere on a bike. I’ve been commuting ever since.” A principal at HTFC, Bonny’s practice has focused on Indigenous involvement in managing lands and natural resources.

A self-proclaimed “suburbanite,” Bell lives in Sage Creek with her three kids and husband. Bell works as a human resources consultant in health care by day, and moonlights as a digital influencer and blogger by night. While her job has her navigating the city and to and from meetings by way of car, she recently bought a bicycle as a way to explore the city.

“I ride around Sage Creek all the time. I ride the Bishop Grandin Greenway. I try to ride as much as I can just to have an evening to myself. I love my city. I love what we’re doing. And I love the Bike Jam.”

The quartet talked about ways to encourage and support cycling in the city, and how local initiatives like the Bike Jam provide participants with an opportunity to find new neighbourhoods for the first time and to experience urban space from a different view.

Can you tell us about the Bike Jam — why it was created, who helped support it, and what impact it has had since its first ride?

● Belford: Bike Jam started with my friend Luke’s birthday. It was a very warm night for a September and his birthday events were winding down but we still had a lot of energy. So we decided to grab a portable speaker and put our iPod in it. Ben, Luke’s brother, and one of the co-artistic directors for Rainbow Trout Musical Festival (along with Belford) strapped the speaker to his backpack and then the three of us rode around Winnipeg. It was a party for us. We played electronic dance music. We wore our sunglasses at night and had the best time. I’ve had many moments cycling through the city at night but that night, in particular, was my favourite because we added music and stayed up late. The streets felt like they were ours. We didn’t get home until 11 a.m. the next day. That’s the tale that started circulating, and people’s interests were piqued. So, we started inviting more people. On Canada Day, we called our friends and they called their friends to come out for a bike ride. At different events, we’d assemble a crew of friends and have a huge party and ride. The thing that persisted was the playing of the music — that elevated the whole concept of cycling in single file. We wanted to be as close to each other as possible so we could hear the music. People on the street would say, “Play this song!” The first official Bike Jam brought out 30 people. Andy Rudolf, who works at Artspace and is a musician and audio technician, helped us rig the biggest speakers on the back of a bike — he knew just what to do! So now, we have an inventory of scooter batteries, a half dozen amps — and now, we solder these all together in advance of a Bike Jam, put it on the back of a utility rig, and go for our ride.

● Thomas: Was it somewhat random? Or did you have the route planned ahead of time?

● Belford: We always do a pre-ride. And now we have two dozen volunteers. Pre-rides are an event in themselves. When we first started Bike Jam, we were more nimble and could get into smaller places because there were fewer people to worry about — pre-planning wasn’t always necessary.

● Thomas: The volunteers help to make sure people don’t get broken up as a group?

● Belford: Yeah, there are leaders, corkers, and trailers! The leaders are the pace car. They stay at the front, and make sure no one goes ahead of them. The trailers are like, “This is the end of the Bike Jam — if you’re with us, stay ahead of us!”The corkers are the leap-frog team that go from intersection to intersection and help with crowd control. They’re like the faces for the event — helping to acknowledge the cars: “I see you! You see us! This is not normal! But we’re having fun! And we’ll be through in a minute!” I think that’s an important part to Bike Jam — we let people know that we’re self-aware and that this isn’t an act of defiance, it’s a celebration of the city.

● Bell: It’s about creating a sense of community. I met so many people from that night when I went. It was amazing. I tell everyone everything so I make a point of telling everyone about Bike Jam and how it is such a great way to feel comfortable on the street!

● Belford: The thing about the Bike Jam is that it’s fun. It’s about riding to places that you normally wouldn’t go on a bicycle. We’ re not so brazen as to ride through Portage and Main… yet! But it’s really amazing — riding through intersections and everyone has a lot of positivity. It’s instilled into the group that it’s not a protest, it’s a celebration and everyone can come along. We have a catchphrase, “Smile and wave!” People are pumped. The feeling of doing that and having others wave back at you, and residents dancing as you bike by, that’s what it’s all about. It helps you experience and take in the city.

As Bike Jam gets bigger, how do you keep the original message of it?

● Bonny: With Bike Jam, it’s about a fun Friday night. You’re bringing out all types of people.

● Bell: But there are people who are cyclists. My cousin, for example, loves to cycle everywhere. We brought him to the Bike Jam and he loved it. He’s usually the type of guy that goes where he wants to go and has his routes but he was easily persuaded by Bike Jam and loved trying something new and learning from others. It’s more about fun than it is about protest. It’s a mixture of the two though.

● Belford: We recognize that there is a message that gets conveyed whether the intent is political or not. I definitely don’t think this is an event that is just for cyclists or it’s a cyclist event, it’s for people who like to bike and want to have fun.

How important is this type of grassroots cycling advocacy in informing and influencing design in the city?

● Bell: If folks are open-minded and see a whole bunch of cyclists, they would be like, “Wouldn’t it be nice if these people had a proper lane to cycle on?” as opposed to thinking, “These people are in my way.” Open-minded Winnipeggers appreciate change and want to see their city improve. They may even get involved with the Bike Jam, and advocate for more bike lanes and bike-related infrastructure to foster more cycling in Winnipeg, versus the shaking of the fists. When I was on my first Bike Jam, there was some shaking of the fists, but they wouldn’t get out of their cars. Why? Because there were a thousand cyclists! Strength in numbers.

● Thomas: It certainly sounds like the volunteers are friendly and are about having a good time. They aren’t saying: “We’re mad. We’re here. We’re cyclists.” They’re more like, “We’re citizens and we’re having a good ride through the city.” That approach in itself gives people in their cars a different view into what cycling can look like. It has a temporary impact on traffic like a Santa Claus Parade — do you get angry about it? Bike Jam is like that.

● Barteski: I don’t bike a lot because I don’t feel safe biking downtown. I don’t feel confident in my own bike skills. Participating in Bike Jam gives you the muscle memory to continue trying to cycle: “Hey I can do this, I’m biking downtown!”I feel safe because I’m with all of these cyclists. It’s good for the cycling community, to change people’s perceptions.

● Bonny: It’s about creating that safe space. I like that Bike Jam was organic — it just happened. Events like Ciclovia were based on a model that existed elsewhere and it was brought here, whereas Bike Jam just happened. It’s very honest and very authentic.

I like how Bike Jam emerged as part of a birthday celebration. My friend Andrew planned a similar event, where a bunch of our friends signed up to serve an appetizer, entrée, and dessert. We visited each home and then biked around the city. How can Bike Jam help to expose people to different types of neighbourhoods and people?

● Thomas: There have been many bicycle studies and plans done by and for the city, and only recently it seems like things have started to stick. But there have always been safe and interesting bicycle-friendly routes, through most of Winnipeg’s neighbourhoods. With bicycle signage and maps, you can explore these routes and discover connections. So I think that’s cool about bicycling. If you’re in a car, you stick to your route. The best bicycle route is often the quiet street that’s parallel to an arterial street. Many neighbourhoods lend themselves quite well for bicycling, but there are places and streets where travelling by bike can be unnerving, if not dangerous. Projects that provide safe passage around such barriers, linking existing routes, are creating an amazing and extensive bicycle network, for relatively little cost.

● Belford: There’s certain places that we go all the time and there’s certain places that we just can’t get to. While I grew up in the south and all my friends were raised in Whyte Ridge, St. Norbert and Fort Garry — we’ve never taken a Bike Jam over to these parts of the city. We just can’t figure out how to do it, unless we start down there and just stay there. We like starting centrally because everyone comes. Going down Pembina and taking the underpass would be incredibly terrifying for a lot of participants. I’ve ridden that route umpteen times but it’s tough.

● Bonny: Do you stop at parks for events?

● Belford: Yeah, we definitely stop at many parks. Especially at night!

● Bonny: You have this safety in numbers for people to feel safe going to these parks in the evening. You’re using all these parks and designed public spaces. You’re bringing people to places that are meant for people. Could Bike Jam get big enough that it is considered a “user group” for engagement when these spaces get re-designed?

● Belford: Put my name on that list!

Is Bike Jam free?

● Belford: People donate. It allows us to do stuff. We did a pizza cookout in the North Point Douglas park on Rover. We made dozens of pizzas and handed out slices to the community. Donations help to support future rides and adding new and exciting features to it.

What support should the city provide?

● Belford: For a baseline, just as a person who rides a bike, keeping bikes in mind with new projects and knowing that it’s not a debate. That questions like “Do people bike? Do people bike enough? Is it worth it?” shouldn’t even be asked anymore. If you make streets inhospitable then people are not going to bike. If you want to see people on bikes, just give them the opportunity. Give them a comfortable place to put the Chariot (trailer), to put the groceries in a nice big bike that can handle it.

● Thomas: So here’s an interesting question. Because bicycling is becoming trendy and attracting attention and there are events like Bike Jam, it’s turning things around and building positive attitudes. And the numbers make a difference because it makes politicians pay attention. When I was riding in the ‘80s, I must have been one of the first commuters in the city to wear a helmet and it was this big pith helmet. It was just dorky. There were few designated bicycle facilities in Winnipeg yet there were ways to get around on a bicycle. It was amazing. There were abandoned mud tracks and rail yards before The Forks was developed. These were places that people would bike on. It was cool. They’re still there. My father-in-law grew up in Riverview, and he talked about the monkey trails (along the river). They’re still there and kids are riding them. There’s also that bridge that takes you from Wolseley to Wellington Crescent to Omand’s Creek. A car can’t do that. It’s a fun thing to do when you’re on a bike. These shortcuts are interesting and also are the city’s best-kept secrets.

● Bonny: I did my undergraduate degree in biology. I’m thinking about the concept of pioneer species. For example, if there is a clear-cut or burned area, pioneer species are the first plants that come up in the disturbed area, and they create micro-climates that allow other species to grow. Then other plants come and soon you have a hospitable ecosystem. Maybe, as it relates to cycling, the pioneer species were the guys with the dorky helmets like Jim. Now, there are people riding downtown. While not everybody is completely comfortable, there are bikes visible on the streets, and the environment may start to change as the streets become designed for them. Hopefully, with time, the streets will become friendlier, and people will feel more comfortable showing up with their kids in trailers or their six-year-olds on bikes. Maybe we’re somewhere in that continuum right now.

● Belford: Absolutely. When we talk about bike paths, people say that maybe it’s not as good as Ottawa’s or Montreal’s or Portland’s or Amsterdam’s. But even Amsterdam, which is considered to be cycling heaven, was a fairly recent success story. Amsterdam hasn’t always been that and it wasn’t always part of their being. It only happened just a little while ago. That can be us too. Let’s do it.

● Thomas: Going back to Bike Jam, it is exciting to see a mass of cyclists. It shows in a remarkable way the growing interest in cycling in Winnipeg. While cycling as a mode of transport is growing in popularity in Winnipeg, the number of people travelling by bike is still low compared to those travelling by car. But Bike Jam gives the sense of strength or power or profile. But it’s not just the mechanics of moving, it becomes celebratory and it gives that extra look into what the city has. So the fact that Bike Jam is an event means that it’s more than just promoting a new mode of transportation, it’s about community. It’s going to build cred.

Do you get a permit for Bike Jam?

● Belford: We don’t get permits. When we first started, there were so few people that we never even dreamed about getting permits. It grew so organically that we changed and adapted how we were doing things as needs started to evolve. There was only one time when the police shut down the Bike Jam. And we know why: that Bike Jam was really big and we weren’t responding with enough support. After that happened, we started to think about how we could be proactive, and be safe. So we started pre-rides with volunteers, so that everyone knew what was going on. Then we added the positions of leaders, trailers, and corkers. We really do guide through the city. We don’t just go through Portage and Main with our middle fingers in the air. We wait for the red light to turn green and then we go.

● Thomas: It’s almost like the folks who meet up with their vintage cars. That wasn’t organized. That just evolved. There was some concern when it morphed into street racing. And then that was sorted out. It naturally turned into a celebration of people cruising.

● Syvixay: I imagine you start to build relationships with city staff, police, as you become more proactive. I’m sure they just like being communicated with.

● Belford: They do! In fact, I was doing a pre-ride last night, and we were stopped at a red light, and a police car rolled down the window and said, “Hey, are you guys with the Bike Jam?” I replied, “Yeah, that’s us! How did you know?” When we do get stopped by the police, it’s because they just want to check in. More often than not, they’ll get on their loud speakers and shout, “Have a nice time, Bike Jam!” It pumps everyone up. I feel like the police on the street know who we are and what we are doing. In my life as an event planner, I meet people and collaborate with people. People know what’ s going on.

● Thomas: You don’t create cool neighbourhoods for the Bike Jam, the Bike Jam finds them. Bike Jam gives people the chance to explore the great neighbourhoods of the city like downtown and the Exchange District. You find all these funky, interesting parts of the city. It starts to acknowledge that Winnipeg has this really interesting history that so many Western cities don’t have. There are some cool nooks and crannies. Guess what? They look so much better from the perspective of your bike.

● Bonny: I was asking some friends about Bike Jam, and they commented about how it took them to places they had never been before, like the North End. In terms of social mixing in the city and building comfort across communities, Bike Jam helps with that.

Any other comments or questions for each other?

● Thomas: This is the thing that I find so exciting. While Bike Jam is extremely well planned and organized, it is collaborative and feels like a spontaneous gathering of individuals. The Bike Jam and similar community initiatives, in addition to all of the organized activities and festivals, makes the city a great place. There is something to do all the time.

● Bell: I hate when people say there isn’t anything to do! Seriously?

● Belford: My answer to that is, “Just do something. Let’s go!”

Thomas: You wonder if Bike Jam will become one of those events that tourists can participate in. I think we’re still some distance away. Get them to be part of the jam!

● Syvixay: That’s what’s cool about the Bike Jam — it brings people to these hidden spaces, a look into what the insiders know about where to go and what to do.

● Belford: I have this dream where the Bike Jam rolls up and cleans up a vacant lot, and plays baseball. Get them working!