Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Opinion

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/06/2017 (3102 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

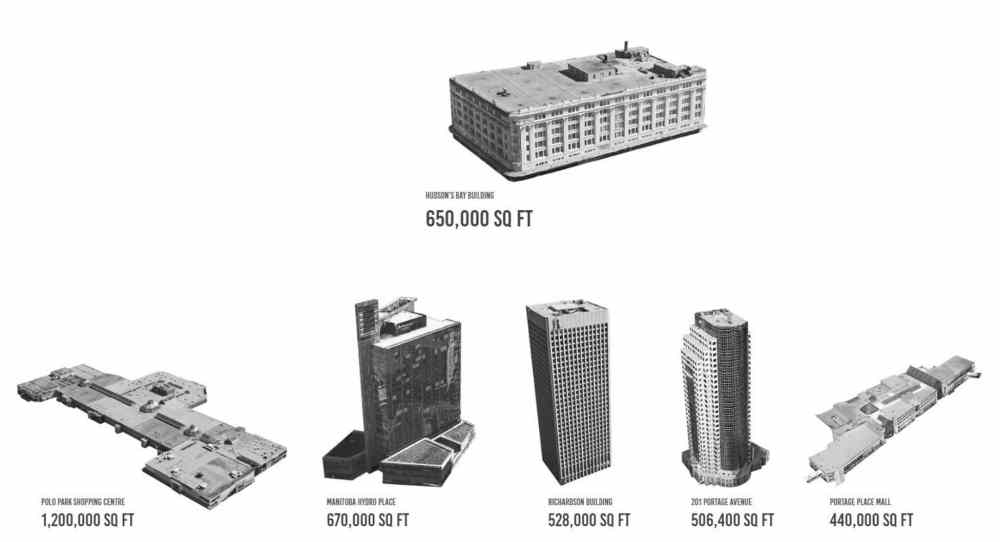

It’s very big. The imposing but nearly vacant Hudson’s Bay building on the southeast corner of Portage Avenue and Memorial Boulevard, one of Winnipeg’s most important intersections, is many things. Big is certainly one of them.

At just over 650,000 square feet, it is a behemoth whose size is concealed by its modest six-storey construct.

That makes the building as big as any structure downtown, rivalled in total square footage only by the largest suburban shopping centres.

It is comparable to Manitoba Hydro’s headquarters, but 20 per cent bigger than the tallest office towers at Portage and Main, and nearly 50 per cent bigger than Portage Place mall.

The floor plates are approximately 85,000 square feet each, large enough to fit both the Centennial Concert Hall and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, with space to spare.

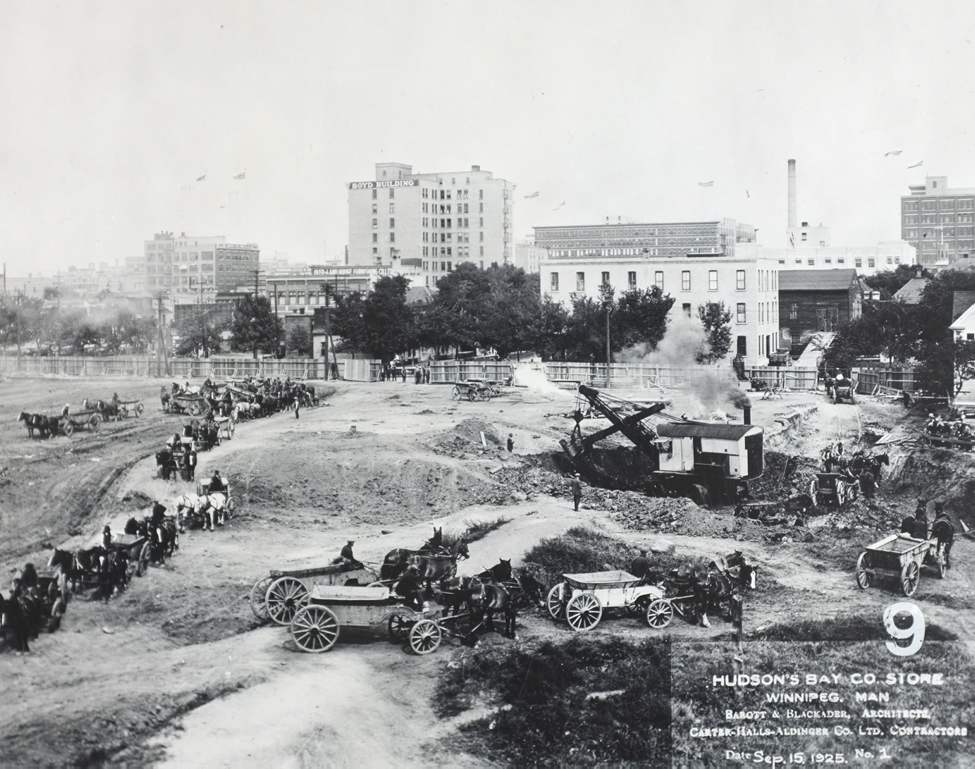

Built in 1925, just five years after the opening of Manitoba’s splendid Legislative Building, the Bay was completed at what was then the astronomical cost of $5 million — almost $72 million in 2017 dollars.

It may not seem like much today, particularly when it costs hundreds of millions of dollars just to build an underpass. But consider that in 1925, Winnipeg’s population was over 200,000.

That’s an incredible investment that reflected both the dynamic nature of Winnipeg’s economy and the culture of excess that characterized the pre-Depression era.

The total cost is also driven by the incredibly high engineering and construction standards.

The Bay building is one of Canada’s most robust and sturdy structures, a marvel of engineering that features 150 reinforced concrete columns that run eight storeys from a sub-basement to the sixth floor. The columns support 50-centimetre-thick concrete floor slabs.

It has a full commercial kitchen as part of the renowned Paddlewheel Restaurant. The sub-basement level featured a 180-metre-deep saltwater well. Cool air from the well was drawn up with fans to moderate interior temperatures during the summer.

The original design even incorporated strategically located structural caissons — deep holes dug down to bedrock and filled with concrete located beneath the building’s foundation — that would allow an additional four storeys to be added to the building at some future date.

There is every reason to believe that long after many of the more contemporary buildings in this city have been reduced to rubble and dust, the Hudson’s Bay building will remain a stoic presence at what serves as the western gateway to the deep core of Winnipeg’s downtown.

Unfortunately, it is nearly abandoned, a consequence of the fact it was designed at the time for a purpose that is no longer viable.

It is too big and too clumsy to be converted into residential or office space as is. Even if someone came up with a design that worked, most real estate industry observers believe it would take a nine-figure investment to bring the project to fruition.

Lingering hopes that it could continue to be used as a department store are vanishing quickly.

The building’s owner and only tenant, The Hudson’s Bay Co. (HBC), is on a slow death march with other traditional bricks-and-mortar department stores, seemingly unable to change quickly enough to adapt to increasingly popular online shopping.

Only the first and second of the six above-grade floors are occupied now by the Bay’s steadily shrinking retail presence, and what’s there looks more like a slightly upscale dollar store than a slightly upscale department store.

The other four floors, and the cavernous basement, are vacant now and trapped in some sort of suspended animation; retail displays, counters and furniture all remain eerily untouched, almost as if the occupants stole away one night when no one was looking.

HBC — which still boasts 66,000 employees and 480 stores worldwide — has fought valiantly to regain its profitability. Controlled largely by U.S.-based investors, the company now includes iconic retail labels such as Lord & Taylor and Saks Fifth Avenue and is reportedly making a play to acquire the Macy’s brand. Outside North America, HBC has expanded into the Netherlands.

And yet, all these acquisitions serve only to mask a depressingly uncertain future.

Just this month, HBC announced it was eliminating 2,000 jobs in a bid to cut costs after confirming that it lost $220 million in just the first quarter of this year.

Add it all up and you have one of the most famous, important and resilient buildings in the history of Winnipeg that is underutilized and inappropriate in its current form for most other purposes.

It is truly the most glorious, most inconvenient building in Winnipeg.

● ● ●

● ● ●

Other than its enormous size, the biggest hurdle to redevelopment of the Bay building is light.

In short, there isn’t much.

Although it does have large, majestic windows carved out of the facade on each floor, many are covered over and those that are open are effective in bringing natural light only to the first 30 feet of interior space.

The deeper you go into the centre of the building, which encompasses most of the square footage of each floor plate, the more artificial light becomes the only source of illumination.

Marketable office, retail or residential development would require access to significant amounts of natural light. It is this challenge that has both haunted and inspired the architects and designers that have tried to “re-imagine” the building as something else.

Recently, StorefrontMB — a coalition of leading minds in the architecture, planning and design communities — hosted a forum at the Winnipeg Free Press News Cafe to discuss concepts for the redevelopment of the Bay building. The event was part of a StorefrontMB-Free Press series to re-imagine the city’s design and architecture.

Two architects made presentations on the Bay building: U of M architecture student Aaron Pollock and Dudley Thompson, founding principal of Prairie Architects. Both independently conjured new designs to bring more natural light — and new life — to the historic structure.

“The lack of light is a significant detriment to the building,” said Pollock, who devoted his master’s thesis to the question. “If you want to do something else with this building, you have to find a way to bring more light into the equation.”

Thompson noted that it is quite unlikely a building like the Bay would be constructed today without some accommodation for atria to bring natural light to the interior.

In fact, it is unlikely any multi-storey building would be constructed today with such a broad footprint. When developers want to create a building of significant square footage, they typically build up rather than out to ensure there are no problems with light, he added.

Thompson said that current design and environmental standards require that the interior space of any new building be no further than 15 metres away from a source of natural light. The Bay building is 70 metres wide and more than 120 metres long, creating what is, in effect, an expansive black hole at the centre of the floor plates, he added

“Light is absolutely key to whatever you do in terms of design,” said Thompson. “Right now, you can really only use the perimeter of the Bay building. The rest of it is really of no use.”

Both Pollock and Thompson believe the solution to the problem is to cut out sections of the building’s interior to allow natural light to flood in. Although this would be difficult from an engineering perspective in most modern buildings, in the case of the Bay building, the strapping internal concrete frame makes removing entire sections a fairly simple matter.

Imagine constructing a building of similar dimensions with Lego blocks. Each floor of the building would feature 150 Lego columns that stretch from the base to the very top. Then, go into the very middle of your Lego building, and start removing some of the centre-most pillars; the surrounding pillars, and thus the building, would be unaffected.

The Bay presents a similar opportunity. With only a few load-bearing exceptions, entire sections of the interior concrete structure can be removed — either on a single floor or a series of floors — without compromising the overall structural integrity.

This allows for the creation of shafts that, if shaped and positioned properly, can bring natural light deep into the interior of the structure. It can also help to create communal areas: courtyards, plazas and other spaces that have an almost park-like sensibility. Across these gaps, new staircases and ramps can be created to change the way people move up and around the building.

Thompson said this kind of design approach has already been used in older buildings in other cities around the world that suffered from the same lack of natural light. Three in particular caught Thompson’s eye: Butler Square in Minneapolis; Queen’s Quay Terminal in Toronto; and Tip Top Lofts, also in Toronto.

Bringing new life to old buildings

Three repurposed buildings in particular drew the attention of Dudley Thompson.

Butler Square in Minneapolis involved the conversion of an architecturally significant warehouse built in 1908.

Queen’s Quay Terminal in Toronto is an art-deco style cold-storage warehouse built in 1926.

Tip Top Lofts is the former head office and factory for Tip Top Tailors.

Butler Square involved the conversion of an architecturally significant warehouse built in 1908. It was converted in the 1970s to mixed use, largely through the creation of two large atria to bring light deep into the interior. The frame of Butler Square was constructed with enormous Douglas fir wooden beams that were strong enough to allow for sections to be removed without compromising structural integrity.

Both Queen’s Quay Terminal (art art-deco style cold-storage warehouse built in 1926 and converted in the 1980s) and Tip Top Lofts (the former head office and factory for Tip Top Tailors, built in 1929 and converted in the early 2000s) feature concrete-column construction that is nearly identical to the Bay building in Winnipeg.

In both Toronto examples, residential development was a key to the economics of the projects. Four storeys of condos were added to the Queen’s Quay building; six floors of condos were added to Tip Top Lofts. Significant sections of the interior structures of both buildings were removed to create dramatic pockets of open space complete with breathtaking mezzanines and balconies and new connections between floors.

Thompson said his re-imagining of the Bay building was influenced by those projects. After adding three storeys of condominiums to the top of the building, Thompson envisioned creating at least two large atria — one on the south end of the original structure, the other on the north side — to bring light into the interior.

As an added feature, Thompson said he carved out a tunnel through the centre of the ground floor that would serve as a transit corridor connecting Graham Avenue with Memorial Boulevard.

“From a design and engineering point of view, it’s very simple really,” Thompson said.

“All of the columns will, for the most part, remain. You just have to cut out the floor slabs between the columns, and that isn’t very difficult at all.”

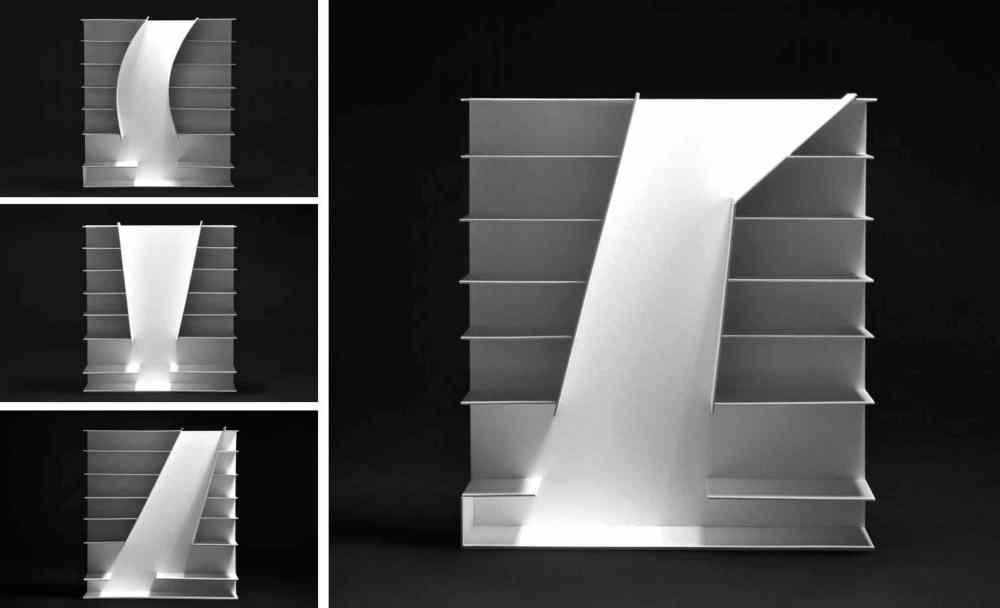

Pollock’s plan is similar, although much more ambitious in terms of the design of the light shafts and atria.

He envisions highly articulated shafts that snake their way from the roof level deep into the interior structure. Each is shaped and angled in such a way to catch the most natural light as the sun passes overhead.

On the exterior, entire sections of the Tyndall stone facade have been cut away to add even more light to the interior.

Inside, new walls, ramps and staircases connecting the levels are also given dramatic angles. Utilizing the rigid geometric symmetry of the original structure, Pollock has introduced a degree of asymmetry that is still well within the reach of real-world engineering capabilities.

Much as is the case with Thompson’s proposal, Pollock envisions a building of true mixed use: bistros, bike shops and a large downtown grocery store mix with other retail on the lower levels, with funky office space on the middle floors, extending up to residential development above.

“I didn’t want it to be too crazy,” he said. “I wanted to show people the true potential of the building, and that it really could be completely transformed thanks to the way it was originally constructed.”

•••

For every dreamer with a grandiose plan there must be someone grounded in the hard realities of economics and business. For the most part, that person is Angela Mathieson.

The CEO of CentreVenture, the city’s downtown development agency, has no official involvement in the fate of the Bay building. Still, given the precariousness of its situation, and the nature of CentreVenture’s mandate, Mathieson has spent a considerable amount of time coursing through all possible options for future redevelopment.

Reusing the building more or less as it is. Bisecting it and creating multiple free-standing structures. Driving multiple light shafts into the interior space. Adding floors to the top of the building to expand the future revenue-generating potential.

After studying all the options, Mathieson has arrived at one inescapable reality.

“This is a really huge and expensive project,” she said.

How huge and expensive? Mathieson said there are two main areas where financial concerns come into play.

First, there is the issue of acquiring the building from its private owners. And second, there are the costs involved in turning it into something else.

On the first — acquiring the property — the hurdles are profound.

It is widely accepted that despite the life-and-death struggles currently faced by traditional department-store chains, the Hudson’s Bay Co. is not actively shopping it’s Winnipeg flagship store around. Rumours in the real estate and development sectors suggest the company has had discussions with a few tire-kickers, but nothing serious has resulted.

The closest that anyone has come to prying the building away from HBC was in 2012, when it was learned the company had offered to gift the building to the University of Winnipeg. Ultimately, the school was scared away from the offer because of the enormous costs of both maintaining the existing structure and the astronomical price tag for a conversion necessary to make it practical space for academic use.

Lamentably, Lloyd Axworthy, then the university’s president and chief intermediary with HBC, had no luck trying to assemble a consortium of public and private interests that could have helped spread out the cost of redevelopment. There is no evidence HBC is still interested in giving the building away to anyone, and the company has declined numerous requests from the Free Press to discuss its future.

Mathieson said all interested parties would be well advised to assume now that HBC wants to be paid for the building. That is problematic, she said, because when you consider the costs of converting it into anything approximating the visions created by Thompson or Pollock, the building really has a negative value. That is a real estate industry term that describes a property that costs more to bring into service than its current value.

In very rough terms, Mathieson said she can imagine HBC looking to get somewhere north of $20 million for its asset. That price may be prohibitive when all of the work that needs to be done to bring the building up to contemporary occupancy standards is factored into the equation. In addition to renovations to bring more natural light to the interior, the building would require a complete overhaul of its fire-suppression, HVAC, plumbing and electrical systems.

Which brings us to the second issue where money comes into play: the cost of conversion.

There is no firm price tag associated with any proposal, but Mathieson said a plan of that magnitude could easily cost upwards of $150 million. A private developer may be able to eventually recoup the money necessary to pry the building from HBC, but most observers believe it would be an extremely difficult task without some sort of government involvement.

In this province, at this particular point in time, that is going to be a really tough sell.

Premier Brian Palllister’s Progressive Conservative government has made it clear that while it battles to reduce a chronic budget deficit, it does not have money to invest in signature infrastructure projects in the city’s downtown.

After being elected in April 2016, Pallister has cancelled construction of a $300-million building for CancerCare Manitoba and a $75-million plan to convert the Medical Arts building on Kennedy Street into the new headquarters for Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries. The province has also refused to confirm a $15-million contribution to the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s new $65-million Inuit Art Centre, now under construction on Memorial Boulevard across the street from the Bay.

Using those decisions as context, it seems rather unlikely the province would advance money to help acquire the Bay building and put it into the hands of a government-led consortium.

Unfortunately, the province’s aversion to projects such as this has trickled down and dampened the city’s enthusiasm. The recent provincial budget froze or cut grants to municipalities. In a recent interview, Mayor Brian Bowman said that while he has high hopes a solution will be found to transform the Bay, he “could not see a scenario” where the city would advance any money to help acquire the building.

Thompson said that government’s reluctance to get into the project is largely driven by the fact that no one knows for sure how much it would take to acquire and redevelop the building. If government does not want to buy it, then certainly the city and province should be able to find some money to do a detailed feasibility study to find out exactly what would be involved to realize the building’s full potential.

“A feasibility study does not have to cost a lot of money, but it could answer a lot of questions and show people that this can be done,” he said.

Others, like Jeff Palmer, chairman of StorefrontMB and founder of Catapult Community Planning, argue that government’s aversion to getting involved in the Bay conversion is short-sighted. Palmer said that while the total price tag may scare off public and private investments, the economic upside would likely protect anyone who got involved in helping to kick-start the conversion.

In terms of financing the project, government has many options to explore before considering an outright advance of cash to buy the building, Palmer said. For example, the province could allow an agency such as CentreVenture to borrow money at preferential government interest rates to acquire the building and start the process of looking for partners and tenants to develop and occupy different levels, he added.

“We know it’s technically feasible,” Palmer said, referring to the renderings done by Thompson and Pollock. “But in terms of economics, it can also be done. The size of the project is so great, it will take some time to fill it up. But if we do it properly, it can definitely be filled up.”

It has been generally presumed that there is no rush to redevelop the building, largely because it is built to standards that make it one of the most enduring structures ever seen in Winnipeg. But Thompson said that it would be a mistake to think it can remain in its current under-utilized state for an indefinite period and still be eligible for a makeover.

The building is too important from a historical and architectural point of view to take a casual attitude towards its future, he said. Rather than a single structure, government needs to recast the building as an infrastructure project, no less important than building a bridge or resurfacing a highway.

“It’s such an important building, and has so much potential,” Thompson said. “But unless we, as a community, are proactive, it will at some point just implode. And then where will we be?”

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, June 17, 2017 1:09 PM CDT: Photo changed.

Updated on Tuesday, December 4, 2018 9:26 AM CST: Corrects typo