Confidence on tap

Urban breweries serving up investment and pride

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/05/2017 (3129 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Winnipeg’s positive redevelopment efforts and sense of community innovation are major draws for creative people outside the province. Kevin Selch, Braden Smith, Mark Bauche and Shannon Baxter are all non-natives to Manitoba, but each has found a home here, both for themselves and their creative endeavours.

Selch is the owner of Little Brown Jug, a 10,000-sq.-ft. brewery on the fringe of downtown’s Exchange District. He was born in Tisdale, Sask., and raised in Winnipeg. At 18, he left the city for university in Wisconsin and later migrated to Vancouver to further his studies. He worked in Ottawa as an economist for 10 years, then got to work on a business plan and moved back to Winnipeg in 2015. It took nine months to build out the space; now Little Brown Jug has been open for several months.

Smith has been Winnipeg’s chief planner for four years. He grew up in the Kootenay Rockies and then found himself in Tofino on Vancouver Island where he served as the town’s chief administrative officer. Smith marvels at the fact he has an incredible opportunity to work in land-use planning in one of Canada’s fastest growing cities: “Our growth rate has actually exceeded Toronto’s, Vancouver’s, Montreal’s, and Ottawa’s over the past two or three years and so it’s a really exciting time to be in Manitoba.”

Bauche and Baxter both moved to Winnipeg to study landscape architecture at the University of Manitoba.

Bauche was born in Weyburn, Sask., and has been with HTFC Planning & Design for more than 11 years. Bauche has volunteered much of his time advancing the landscape architecture profession through the Manitoba Association of Landscape Architects (MALA) and recently installed Big Red, a Cool Gardens installation built near the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Not surprisingly, Bauche drew on his hometown roots by joining up with his friends from Saskatchewan to design and build it.

Having grown up on a farm outside the hamlet of Demaine, Sask., Baxter’s design practice stems from a desire to be outdoors. “I had wanted to be an interior designer. Thank goodness that didn’t happen because I realized I hate being inside, so why would I design interiors?” After working in Alberta for a time, she moved back to Winnipeg to complete her Master of Landscape Architecture, and joined HTFC Planning & Design in 2007.

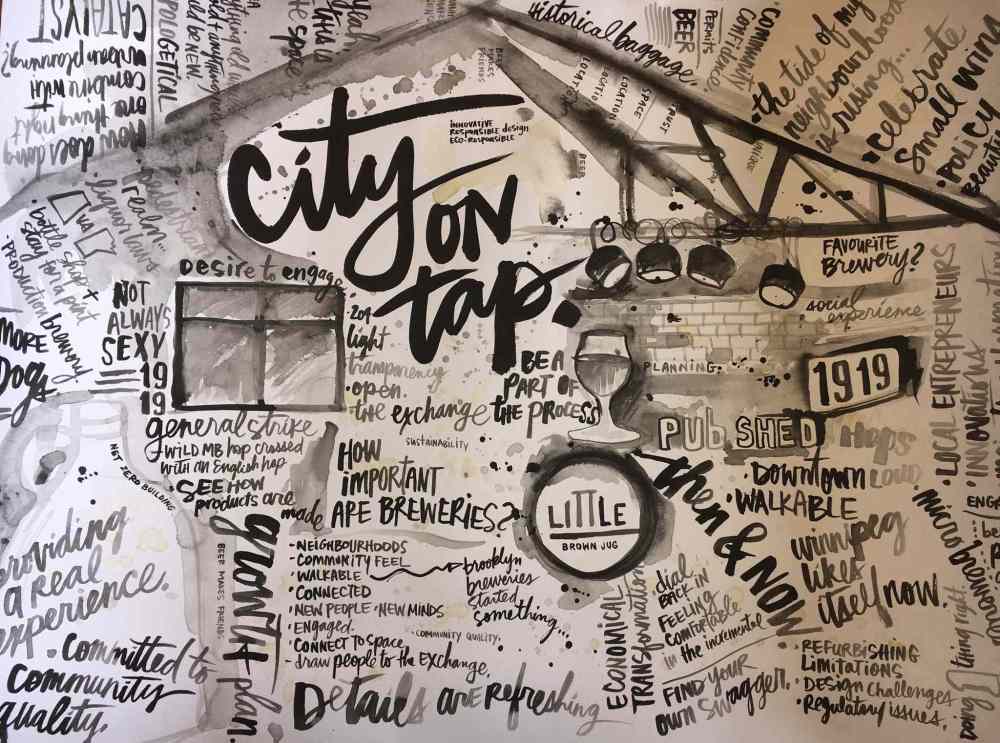

Discussion brewed around Winnipeg’s newfound confidence when Selch, Smith, Bauche and Baxter gathered over pretzels and craft beer. The quartet acknowledged the impact of urban breweries in creating a sense of arrival and pride in the Exchange District, a feeling of investment, and a desire to renew the art of “making” with one’s own hands.

Many breweries are opening up in the downtown. Why do you think this is?

● Smith: There’s a strong connection between local breweries and the environment that they are in. Our downtown has a fantastically diverse and intact pedestrian realm. I think there is a strong connection with these conditions and the emergence of breweries.

● Baxter: Were the liquor laws not changed that have made it easier for breweries to open up?

● Bauche: Winnipeg was way behind, very 1950s. I used to get jealous when going back home to Saskatchewan because there were tons of new brew pubs in Regina, and so many other places. Manitoba’s finally opened up these laws and it’s great to see.

● Selch: I always planned on coming back to Winnipeg even before the laws were changed. In our business plan, I knew we’d have the bottle shop, which is a big part of our business — so anyone could come in and pick up their beer. The major change now is that taprooms are allowed, so people can come in and stay for a pint.

How much of this success is attributed to entrepreneurs, designers and planners looking to create a walkable downtown?

● Smith: Downtown is a fairly permissive land-use regime but with certain regulations. The success has been an iterative and collaborative exercise between many parties, but driven in large part by entrepreneurs.We want to use our space in innovative ways… On the community side, our space should be used.

-Kevin Selch

● Selch: The city just made changes about where brew pubs could be located. I’m sure that comes about with an entrepreneur wanting to do it, provoking that discussion.

How many breweries is enough? Will Winnipeg reach a saturation point? Why or why not?

● Selch: I don’t think we’re anywhere near that yet. When I lived in Ottawa, I would go down to Vermont. Vermont has nearly 600,000 people and around 40 microbreweries. So there’s a lot of space in the Winnipeg market for new breweries.

Can breweries pioneer communities?

● Smith: I think it provides an opportunity for a connection to the pedestrian realm and the larger community. Local pubs are in our DNA; they bring back some energy into surrounding neighbourhoods.

● Selch: There are many examples where breweries have had transformative impacts on urban centres. The Brooklyn Brewery in New York is a prime example. Opening in the mid ‘80s, it helped transform the neighbourhood into a vibrant place, to a point where the brewery couldn’t afford the higher rents and had to move.

For us, Little Brown Jug draws in so many different people into the downtown, a real cross-section of Winnipeggers. We want to use our space in innovative ways. We’re hosting yoga in here and in the summer, we’ll become a pick-up location for community supported agriculture boxes! We even hosted a bubble hockey tournament. On the community side, our space should be used.

● Smith: I’ve been thinking a lot about how our city helps to facilitate economic development activities and often times, we spend a lot of energy on capturing the next big manufacturing business or call centre because they help promote jobs and growth in the city.

But I think local entrepreneurs also transform the community. We talk about “ped sheds”– how far you can walk to certain amenities. In Winnipeg, a “pub shed” is emerging.

I think the community is seeing the level of investment and commitment in social capital. People start to think, “Something is going on here! My neighbourhood tide is rising. I want to be part of that!”

From a regulatory and urban planning land-use perspective, I think about what you’re doing here and think, “What can I do as a planner to help facilitate the tide rising throughout the neighbourhood?”

People are looking for those indications that things are changing and transforming. That’s why I see the local entrepreneurial effort as something that is very important and special and we need to find a way to support that as a community.

● Bauche: The fact that this is on the fringe of that area means that you’re helping to bring people here, which will push the area further, making it more of a neighbourhood.

Tell us a bit more about the design of your space. Why was it important for your space to be large, open and with windows facing the street?

● Selch: The idea behind the space was that everything old will be old, and everything new will be new. Anything existing, we left, but then anything we were going to put into the space had to be new and unapologetically contemporary.

All of this wood you see around is 100-year-old Douglas fir that was hanging in between the beams — we just brought it down, cleaned it up, and sealed it off to make all of the furniture in here. With all the stainless steel, there’s a real contrast of then and now.

● Bauche: I think it’s good because it’s not only facing out but it’s also facing in. When you walk by here, you see into the space. You see all of the activity that you wouldn’t have seen before Little Brown Jug. It engages the street. Outside, you see the light from within; inside, you see the sunlight from outside. It engages both ways.

● Baxter: The design really speaks to honesty, one of your business’ principles. You’ve chosen on purpose to be very sparse. You’re not doing super-big colourful motifs; you’re not plastering a lot of big imagery. It’s clean and simple.

Your space is like your brand. It tells you what’s going to be inside. We lack interior spaces that have enough light in winter cities, and we all want a sun catch, so it’s great to have large windows.

● Smith: I have a question about your door. Was it always intended to be on the side?

● Selch: We didn’t have that in our original plan. We had to work through that a little bit because we were refurbishing an old building. There are limitations on what you need to do to meet current code. So the door swing at the front of the building was going to be an issue on the front side.

In the summertime, it would be great to have that front door open up. We’ve talked about chairs and tables in front of our windows so that people can sit outside in front of them.

It would take up no more space than a sandwich board. It’s very cosmopolitan and very modern. But there will be regulatory challenges to do it.

● Smith: This reminds me of a design response that an entrepreneur came up with in Tofino. One day I was in front of a coffee shop, and there were these big rounds of firewood, 18-inches off the ground. When asked, “Is this seating?” They were like, “No, these are just stumps.”

It’s actually quite remarkable that the property line of your building is right at my back. It really closes up that space, that public-private space. There are so many things you nailed beautifully in terms of design.

But I think the logo and how it reflects back to the building acknowledges where you are and your commitment to the neighbourhood. It’s that little nuance; it’s a Winnipeg touch. It’s really well done.

● Selch: The Exchange District is the “Home of Little Brown Jug” and a reminder that we have a stake and emotional connection to Winnipeg.

Selch, your beer, 1919 is inspired by the General Strike. Can you tell us a bit more about that — your process, your inspiration, and how you go about deciding on flavours and ingredients? Do you think it’s important to celebrate Winnipeg milestones through your business?

● Selch: We use Brewer’s Gold as our hop in this beer and that was a Manitoba connection. It was the first commercially available hop in the entire brewing industry, made by crossing a wild Manitoban hop with an English hop. It was made in 1919.

That was the major thrust of our beer — the ingredients, having that Manitoba connection. It’s an important year for our city’s history with the General Strike, too, so the beer is a way to pay homage to the city.

What type of beer for Winnipeg would you brew if you could? What Winnipeg milestone or moment would you celebrate?

● Bauche: I think when they eventually open up Portage and Main. That will be a good time to have a beer. It could be called the Portage Porter.

● Selch: The glass is only half full when you have to run across the street with it.

● Baxter: Right before I moved here, Winnipeg had lost the Winnipeg Jets and had the Flood of the Century. We learned in architectural school about “Little Chicago” and how Winnipeg “could have been a contender.” That was very much driven in our heads, and I think drilled into the psyche of Winnipeggers.

At that time, Winnipeg did not love itself versus when I moved back to Winnipeg for my master’s degree, we had just got the Winnipeg Jets back, there were plenty of cranes in the downtown, and all of a sudden, Winnipeg liked itself. And you could tell. So, for me, there’s been a rebirth. I’d call my beer The Contender.

In a Winnipeg Free Press article, Kevin mentioned how Little Brown Jug should “Do one thing and do it perfectly.” This was in reference to starting with one beer, 1919. This can also be true from a planning perspective — not everything can be done at once. Sometimes incremental change is how communities can generate buy-in from the public and from investors.

How do Kevin’s sentiments connect with urban design and city planning? How can incremental change support long-term planning efforts?

● Baxter: I think that all you need is a catalyst, someone who’s making a product who cares about quality and craftsmanship, and the incremental growth that comes from that. And because Little Brown Jug is here now, chances are another shop will open up across the street, or a residential development will rise next door.

● Bauche: One simple gesture, when you look deep into it, feels more special. You could easily do a whole bunch of little things; it might be more, but will feel like less.

● Smith: You were talking earlier about Winnipeg’s historical baggage and that we have a city that sometimes lacks confidence. Prior to five years ago, the response to development was always, “We need to do something, and it needs to be big and monumental.”

I think this is changing, thankfully. As a city, I think we have a better sense of who we are and where we’re going. We can be incremental and can be great at the things we do.

Kevin, your business approach is very solid. You’ve asked yourself the question: What are we in the business of and let’s dial it in before we move forward. Instead of saying, “Let’s do 12 different taps to compete with Labatt’s.”

For the city, maybe a five-storey template in the downtown is actually reasonable and more viable. Maybe the incremental conversion of our surface parking lots to a development scale that is consistent with many other successful midwest cities is a solid approach to city building.

And being comfortable with that and having confidence and swagger in who we are as a city.

Whether it’s city building or brewing beer, I think authenticity and fidelity to core values is vital. I think that makes a lot of sense here.

● Bauche: Thank you for brewing a Belgian beer that isn’t just a wheat beer. You’ve taken it to the next level with craft and design with its own specific glass. You go to a pub and you get a nice Little Brown Jug glass. It’s refreshing to see that type of level of design thought – and also so very Belgian.

● Baxter: I think a lot of people don’t realize that most design is invisible. When I describe to people at home what I do, I tell them, “We do all the things that you don’t think of or notice.” Planners do all of the things that we just assume happens —people don’t think of the policies that lead them.

As a building architect, it’s easy to point to a building and say, “I did that.” But as a planner or landscape architect, it’s not always as sexy.

When we did the first round of site development at the Winnipeg Folk Festival, some folks didn’t understand where the money was spent because it went underground, to make sure there was enough power, water access, and improved drainage.

Overall, I think it will take more engagement with the public for people to understand the value designers bring. I think entrepreneurs are getting behind design, too, as they are working with us more and more.

Any other thoughts or comments you’d like to make?

● Baxter: I’d encourage more patios. There was a beautiful weekend in November and there was nowhere to have a beer outside. Winnipeggers love the cold.

People want to take a photo and show off that they can embrace the cold. Roll out the red carpet, create cool winter patios, where people can drink outside, enjoy some roasted marshmallows and outdoor games.

● Smith: Last fall, I took a minivan full of city planners down to Minneapolis/St. Paul to meet with planners there and explore innovations in community development and revitalization.

It was interesting to see the relationship between an emerging neighbourhood, like the Warehouse District, and the role new craft breweries have in creating community vitality. One in particular, Surly Brewing Company, was very cool because they had a fire pit that was burning dried wort. It was really pungent.We have a 100-year-old building in downtown Winnipeg and no dedicated heat source. Instead, it will all come from process heat.

-Kevin Selch

But it’s that sustainability practice and getting people outside to interact with the outdoors. I thought that was really cool.

● Selch: We want to do right by the community. So, all of the heat from our boiling goes to our heat exchanger. Once we’re done boiling our wort, we need to drop the temperature down from 100 to 18 degrees before we add the yeast, then it goes through another heat exchanger. All of that heat energy is recaptured and stored for the next brew or to wash tanks. At the very back corner, we have a 24-horsepower chiller and a 10-horsepower air compressor.

We built the room on the inside and we hooked up a system of louvres, so in the summertime, it ejects the heat outside, but in the winter, it puts all of that heat back in the building.

We have a 100-year-old building in downtown Winnipeg and no dedicated heat source. Instead, it will all come from process heat.

We also separated our rainwater from our sewer and our effluent. And as we grow, there’s a little basement, so we’ll be able to treat our water here before it goes back out to the city.

● Smith: That’s huge actually! Let’s take stock of that for a second.

● Barteski: It’s awesome. It’s our job as people of this planet, to make sure our businesses and our lives leave less of a footprint.

Want to duet with us? Email HTFC Planning & Design at info@htfc.mb.ca.

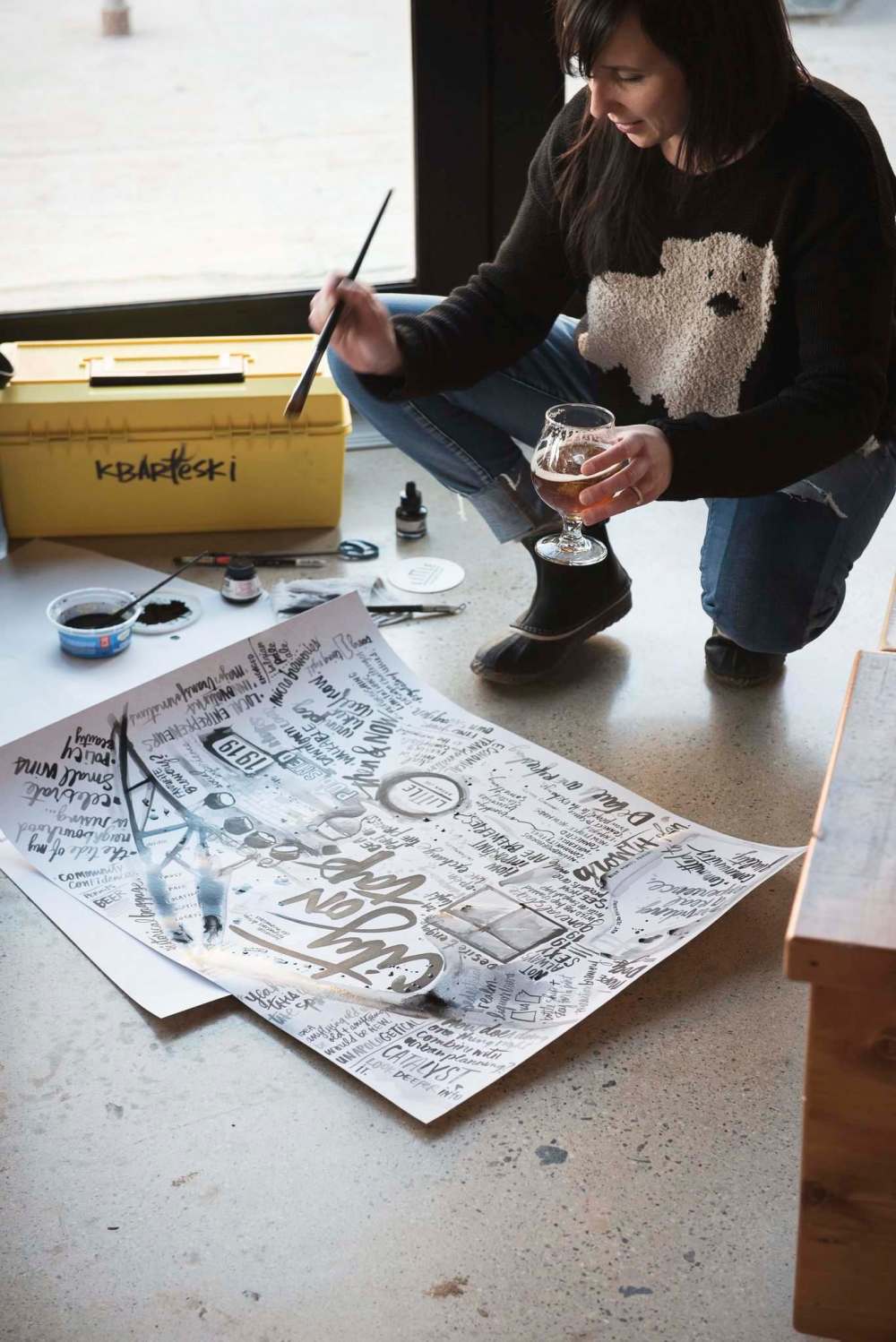

Duets is written by HTFC Planning & Design’s Jason Syvixay, with imagery and photography provided by Kal Barteski and David Moder Photography.