Growing up is a never-ending task

Checking in, halfway through Grade 4

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/01/2009 (5820 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Meet some of Winnipeg’s busiest citizens. They’re currently involved in a long-term development project at one of the city’s most important institutions.

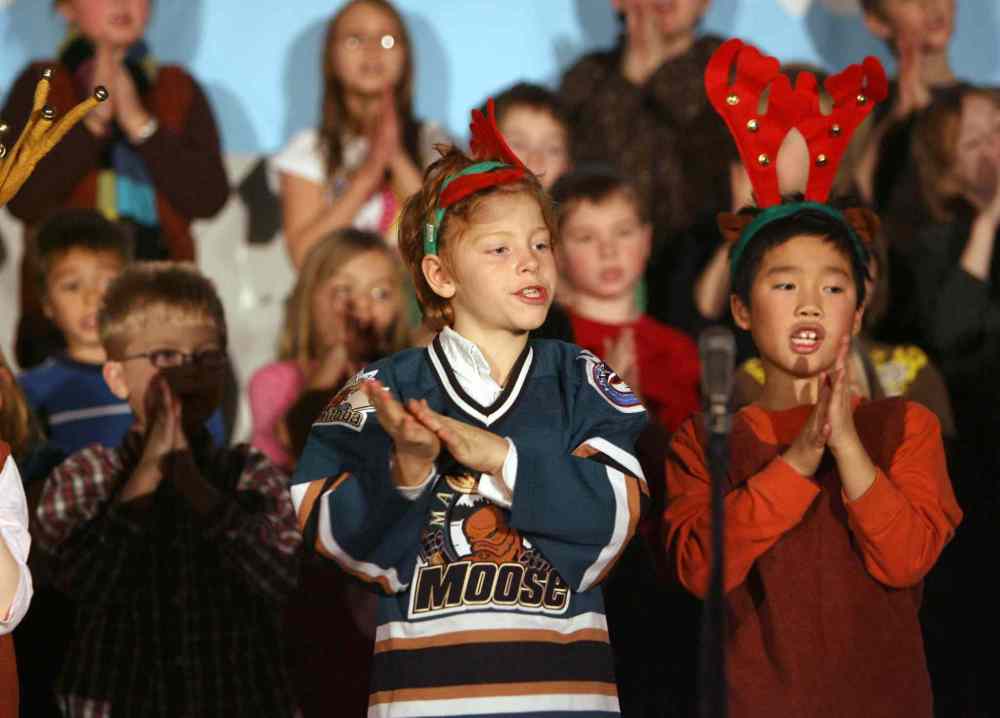

In addition to all the reading, writing, decision-making and problem-solving that entails, they’ve also been learning French, singing in choirs and performing in theatrical productions.

Although their workday officially ends at 3:30 p.m., the busy-ness continues well into the evening — at swimming pools, hockey arenas, scout halls, music schools, dance studios…

When your full-time job is to develop the cognitive, social and behavioural skills needed for adult life, there’s bound to be overtime.

Even if you’re more interested in climbing the monkey bars than the corporate ladder.

Welcome back to the Class of 2017.

"I don’t think kids should be busy all the time, but one or two things after school is good. It gets you active and you learn some things that are useful in life," says Hailey, a Grade 4 student at Windsor School.

Kids have always been busy.

How they spend their time, however, is a relatively recent concern; even a few generations ago, helping the family put food on the table sufficed to keep idle young hands from becoming the devil’s playground.

Today, Canadian children like Hailey typically have around 67 hours of discretionary time each week, which is more than they spend in school.

And when you consider the developmental tasks that await her and her classmates between now and Grade 7, it’s not exactly one big recess.

Middle childhood has long been the neglected member of the developmental family — probably because physical growth is less dramatic than in early childhood and adolescence — but that’s changing as researchers recognize its importance as a bridge between total dependence and approaching independence.

"Evidence is mounting that middle childhood development is a more powerful predictor of adolescent adjustment and success than is early childhood development," Kimberly Schonert-Reichl, a University of British Columbia educational psychologist, writes in Middle Childhood Inside and Out. Her 2006 survey of 1,300 kids was among the first in Canada to explore the psychological and social world of kids aged nine to 12.

As children’s worlds expand to include peers, adults and activities outside of family and school, they begin to try on new roles in which they earn social status — and build self-esteem — by their performance and competence. Experiences of success or frustration in these new settings can play a crucial role in development, experts say, as they either exacerbate or compensate for experiences in school.

Schonert-Reichl notes that developing competence becomes particularly important during these years when children are more heavily engaged in activities that require mastery over something.

Like tap dancing, for example.

Inspired by his cousin’s dance recitals — and a live performance of Riverdance — Liam now spends his Tuesday evenings at a local dance studio. He has no problem being the only boy in class, but recently brought Avery along as a guest to introduce his pal to the joys of the Broadway finish.

Liam also has piano and swimming on Mondays. "Swimming isn’t something he chose, it’s something I put him in," says his mom, Tara. "To me, it’s a life skill."

It’s a skill that now seems to now be mandatory on most parental curricula. "They have to learn how to swim, especially living in this province," says Julian’s dad, Bruce.

Liam is slightly busier than Hailey, who has piano on Fridays and swimming on Sundays, but less so than Aby who, in addition to violin lessons, volleyball, Sunday school, church and occasional volunteering at Winnipeg Harvest, has a job delivering flyers.

"She doesn’t like being really busy," says mom, Mary. "And we always say, ‘when you join something, you have to see it through.’"

Aby started asking for violin lessons in Grade 1, but her parents waited to see if the interest would last. "She was still asking in Grade 2, so we bit the bullet," Mary says.

Sarah, who takes piano and gymnastics, also has a job delivering the Lance with her two younger sisters. "I want them to have music and I want them to learn responsibility with money, and then they have their sport," says mom Kerri.

Gabriel is one of the busiest kids in Mrs. (Donna) Konoski’s Grade 4 class. He has hour-long Kung Fu classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays, piano and two hours of Korean school on Saturdays, plus church and Sunday school.

His mom, Erica, she and her husband are vigilant about ensuring Gabriel and his older brother don’t get overwhelmed by their schedules and that they learn to self-manage.

"I was an over-scheduled child myself," she says, "piano, tap, ballet, art classes, skating, field hockey, Korean school — you name it. Being the child of immigrants, I think my parents wanted to afford us the opportunity to be involved in different arenas.

"But there’s got to be a balance. I want my kids to have a childhood."

Just how heavily engaged kids should be at Gabriel’s age is a question that generates a lot of debate.

Whether he realizes it or not, Liam throws in his two cents.

"If you get high in dancing and you get really old, you’ll end up doing it five times a week," he says.

Winnipeg child psychologist Rayleen DeLuca concurs with Hailey on what constitutes busy enough for a fourth grader.

"The rule-of-thumb is two or three activities besides school — one sporting activity and one artistic activity," she says, "and then you’ll have those children who need to have a social activity, like Scouts, to enhance their interpersonal skills.

"Another rule-of-thumb is there shouldn’t be any actitivity that takes more than a few hours a week."

DeLuca, who has had clients who did gymnastics every day, also suggest kids not focus on a single sport until adolescence. "By the age of 13, three-quarters of children will have shelved what they’re doing, hung up the cleats or Scout uniform," she says.

And just because they say they love everything they’re doing doesn’t mean there’s a healthy balance in place.

"If a child loved ice cream every day, parents would draw a line in the sand," says DeLuca. "Kids need down time just like adults.

"We do know that over the last 20 years, there’s been a noticeable increase in kids’ levels of stress, depression and anxiety — probably because they’re overscheduled."

Well, we were warned.

In his 1981 groundbreaking book The Hurried Child — now available in a 25th anniversary edition — American child psychologist David Elkind warned that the overscheduling of children was leaving them anxious and depressed. Intellectual and emotional growth cannot be rushed since it occurs in a series of stages that are age-related.

Fast forward a generation.

In an open letter to the Class of 2004, Newsweek columnist Anna Quindlen apologizes to the graduates for the stress they’ve been under all their lives.

"I’m so sorry," she writes, "I look at all of you and realize that, for many, life has been a relentless treadmill since you entered preschool at the age of 2 . . . You all will live longer than any generation in history, yet you were kicked into high gear earlier as well. How exhausted you must be."

Today, there are laptop computers for toddlers — plus gadgets to help them surf "pre-school appropriate Websites" —- and a series of DVDs called athleticBaby to give them a head start on the soccer field and golf course.

There’s also a new study out of the University of Maryland that turns Elkind’s hurried-child theory on its ear by suggesting it’s not the busy kids who are suffering. It’s the under-scheduled ones.

In the analysis of children, ages nine to 12, from two medium-sized communities in the American midwest, sociologist Dr. Sandra Hofferth and her colleagues found virtually no difference between the stress levels of those she termed "hurried" — meaning they were involved in three or more activities during the two-day study period, or spent more than four hours on those activities — and those she called "balanced," with one or two activities lasting less than four hours.

It was with the kids who don’t participate in any structured activities (around 17 per cent of the subjects), where differences became apparent.

"Contrary to popular belief, children who are most at risk of being depressed, anxious, alienated, and fearful are those with no activities," Hofferth writes in the conclusion of the study, which is published on the university website.

In his latest book, The Power of Play (2006), Elkind warns that the "silencing of children’s (free, self-initiated and spontaneous) play" by adult-organized activities and passive, electronic entertainment is as harmful to healthy development, if not more so, as hurrying them to grow up.

The good news is that nearly everyone in the Class of 2017 named "playing outside" as one of their favourite ways to spend those 67 weekly discretionary hours. OK, most of the boys also mentioned video games, but Thomas seems to have his priorities clear.

"Outside of school I either play with my friends or on the computer — unless I’m really busy," says the second-year Cub Scout, who’s in the same pack as Garrett. "We’re renovating our house and we’ve got to build more walls."