Taking identity

Knowing who we are despite how others see us

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/12/2012 (4735 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

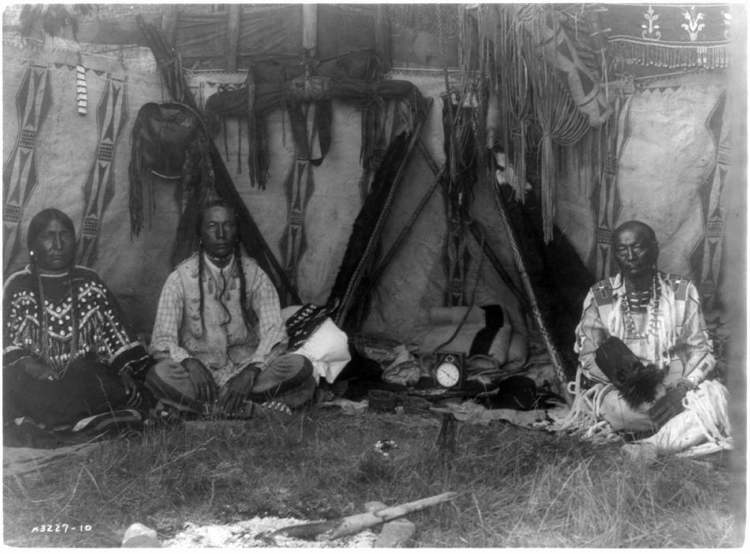

Sometime around 1910, photographer Edward Curtis visited Piegan Blackfoot leader Little Plume at his home in southern Alberta.

By this time, many indigenous communities were relegated to reserves. Most had been exploited by governments and were viewed as a burden. Many endured poverty due to long-standing ways of life altered.

In this, Curtis found a market in Indian portraits. Framed as “disappearing” cultures, his portrayals of head-dressed chiefs, horse-backed warriors, and women in forests received critical acclaim. U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt called his work “truthful.”

What Roosevelt and others didn’t know was that indigenous peoples didn’t look like this. Curtis brought trunkfuls of clothing and objects with him. When his subjects didn’t fit the story he was telling, he dressed them up.

Arriving in Little Plume’s lodge, Curtis snapped a photo. Developing it, he was aghast.

There was a Victorian clock beside Little Plume.

Curtis couldn’t have a dying culture with a clock.

So, doctoring the photo, he removed time.

Recently, I taught Ojibway rap artist Wab Kinew’s 2009 CD Live by the Drum at the University of Manitoba. I asked my students: “What is Ojibway about this music?”

Many identified the use of Anishinaabemowin, the Ojibway language. Some said the beats resembled canoeing. Another argued that anything made by an Ojibway is Ojibway.

“Those are interesting enough definitions,” I responded, “but what do you do with the English in the music? The fact other cultures canoe? Or, that Ojibway now sound like the Borg from Star Trek?”

After further discussion, the defining feature we settled on was that Kinew’s album gave us a sense of a dynamic, changing and growing culture. Utilizing traditional and community practices, the music showed us how a people were entering the future.

Continuing, we determined Ojibway expressions are living processes that connect a unique community with the forces they meet in the universe. Whether encountering wind, an animal or another people, Ojibway ceremonies, songs and stories represent attempts to understand and form relationships within a living universe.

They are offerings, gifts.

By gifts I don’t mean that re-gifted mug. I mean a presentation that illustrates something about an individual or community. This could be history, experiences, or knowledge about the universe. Anything.

Not all gifts instil warm fuzzies either. Some are painful and discomfiting. Truth tends to be this kind of gift.

Once an offering is accepted, Ojibway often expect these to form a bond for a long time. At least until the next time the parties meet and new gifts are exchanged.

What’s Ojibway about Kinew’s music are the gifts that offer who he, his community and his culture are as a growing people. It’s all of it: from the first lyric, sound and message to the last.

Each presents a central message Ojibway know: that we are all related.

This isn’t a new age slogan. It means Ojibway and others are distinct entities but deeply tied to one another. Through sound, word, and movement all are part of a network committed to sharing this world.

We are relatives with shared responsibilities to speak, sing, and act — and allow others to as well.

Family aren’t friends. You treat relations with respect and dignity, even if you don’t like them. You don’t chuck a gift from your sister or uncle in the garbage. You don’t consciously hurt your relatives — because then you are really hurting yourself.

I’m no expert on Piegan Blackfoot culture, but I know this.

By erasing the clock, Curtis was disrespecting a gift.

Little Plume was showing him who he was.

Much of Canadian policy during the last few centuries has been to try to erase parts of indigenous life and replace them.

The epitome of this, the residential school system, sought to “kill the Indian and save the man.”

Everything “uncivilized” in indigenous peoples had to be removed. Language. Culture. Spirituality.

In place was instilled “civilization,” however that was classified.

I shouldn’t have to explain how the residential school system did this. Check the headlines.

Assimilation is an inherently violent practice. To reduce a complex people into a product of sameness, one must employ physical and ideological manipulation to produce a constructed and self-sustaining image.

Sometimes this involves bloodshed.

Other times removal.

Erasing who a people are constitutes genocide.

In recent weeks, the Idle No More movement against the Harper government’s Bill C-45 has sparked mainstream interest in First Nations issues.

Proposing radical changes to legislation, Bill C-45 will expose waterways to industrialization, threaten wildlife, and legitimate the removal of indigenous territories without consultation.

Along with other new laws, Bill C-45 will enable the exploitation of the Earth’s ecosystems and the theft of First Nations territories (among other things).

On Dec. 4, First Nations leaders interrupted their annual meeting to take their concerns to the House of Commons. Arriving peacefully, they asked for consultation. Still, they were refused entry and took their demonstration to the front steps.

Oddly, most Canadian media reported as chiefs “storming” the government. One TV interview described them “clashing” with security. Another pronounced a “backlash … boiling” over.

In the days following, indigenous peoples and their allies converged on malls and legislatures to demand clean drinking water and safe communities, partnerships based on treaties, and consultation on environmental and economic policy. One chief has even staged a hunger strike to demand a meeting with the prime minister.

Harper and his government, ignoring all calls, passed Bill C-45.

Activists, however, continue to demonstrate. And how?

Round dances mostly.

In other words, they’re giving gifts.

Few communities have continually changed — and in such drastic fashion — as indigenous peoples.

It could be said that motion constitutes indigenous existence.

For instance, as indigenous peoples encounter new technologies, their names, languages and stories change. As writing systems like birch bark and YouTube are adopted and adapted, traditional practices innovate to include them. As new dances, music styles, and Twitter hashtags encompass political struggles, indigenous expressions radically alter.

Not all practices need to, or should, change. Giving tobacco and prayer have been a good way to communicate with spirits for a long time. MP4s do not replace orality. E-mail cannot substitute visiting. You get the point.

In Manitoba, indigenous peoples have been embodying motion for thousands of years. You can see this in writings throughout the province: in stones of Manito Ahbee, rock paintings near Sagkeeng, tattoos on bodies. In the footsteps of flashmob round dances.

The Forks is Manitoba’s first, and oldest, Internet. People have been travelling in and out of this site for centuries, trading and leaving stories written in footsteps.

Today, motion resides in treaties, novels, and websites.

Our relationships are found in all of these spaces.

This is why resisting acts of erasure, like Bill C-45, is so important.

Protecting our relationships are about protecting who we are. These are spaces where we collect and give gifts to relatives throughout the universe. These are the spaces we share our gifts with Canadians, too; here are found the history books of this country.

Our relationships are forged not only today in waterways and on land, but in malls and legislatures. We must protect these places too; they constitute our living world.

Our relationships give us motion. Without them, indigenous peoples can’t exist.

All that’s left is a dead, lifeless picture of the gift-givers of this land.

A constructed image. Void of motion and time.

And an empty, meaningless Canada.

Friends, not family.

And we’re more than that.

Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair teaches in the department of native studies at the University of Manitoba and co-edited the award-winning book Manitowapow: Aboriginal Writings from the Land of Water, the first historical anthology of indigenous writings in Manitoba.

History

Updated on Saturday, December 29, 2012 12:24 PM CST: adds photo