Fighting words For nearly 150 years, the Free Press has provided readers with a detailed record of armed conflicts

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/11/2022 (1218 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The Free Press has been in the trenches for a long time.

Whether the banner on the front page read Manitoba Daily Free Press, Manitoba Free Press, Winnipeg Free Press or — as it does today — simply The Free Press, the newspaper has kept readers up to date about Canadian war efforts here and around the world.

It’s a long legacy, stretching back 150 years.

Robert Young, professor emeritus in history at the University of Winnipeg, once took a deep dive into Free Press archives to write his 2015 book Premonitions of War: The Winnipeg Free Press in the Hitler Years. He has long been an admirer of the newspaper’s coverage, especially its editorials in the 1930s in the run-up to the Second World War.

Because the editorials were — and still are — unsigned, the public never knew who wrote them on any given day. It could have been legendary editor John W. Dafoe, who was executive editor of the paper from 1901 until his death in 1944. Or maybe George Ferguson, an editorial writer who became executive editor when Dafoe died. Or some other unnamed member of the editorial board.

Regardless, it always seemed like they were written by the same hand, Young says.

“I was struck by how consistent the paper had been in going after regions that attacked human rights,” he says. “It was really consistent that people should not be treated this way. How pre-emptive and how persistent the paper was. It really was impressive.”

When the first issue of the Manitoba Free Press was published on Saturday, Nov. 30, 1872, there was no war reporting demanding readers’ attention. The entire front page was dedicated to the Dominion Lands Act.

The establishment of the newspaper in a town of just 1,500 residents came two years after the Louis Riel-led Red River Resistance resulted in the creation of the province.

Riel would figure prominently in subsequent coverage 12 years later when the North-West Resistance, known as the Rebellion then, broke out.

Under the heading Rebellion News, the Free Press promised several times during the conflict that “the public may rely upon it for the Latest, the Fullest, and the most Accurate reports.”

The Free Press noted that, in partnership with “a leading eastern paper,” it had special correspondents embedded with troops under British Gen. Frederick Middleton, commander of the North-West Field Force sent to suppress the Rebellion, and Canadian-born Col. William Otter. Their instructions were “to spare no expense in forwarding absolutely reliable news at the earliest possible moment.”

“Whether the campaign be of long or short duration, the same exertion will be made to give the readers of the Free Press exactly what the public want and have a right to expect from any newspaper worthy of the name — reports of actual occurrences, as soon as possible, as distinguished from the mischievous imaginings of war correspondents located in the ‘home office.’”

Lofty expectations, indeed.

It marked the beginning of battlefield reporting by the Free Press.

From the work of those first two special correspondents to that of National Newspaper Award-winning columnist Melissa Martin from Ukraine earlier this year, the Free Press has reliably published news of international and local conflicts as seen through a Manitoba lens.

The event that triggered the First World War was just one of many stories on the front page of the Monday, June 29, 1914, edition of the Manitoba Free Press.

Next to a story detailing how a Brandon woman, who acted as a fence for a gang of young thieves, had been convicted, was one about the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria, and his wife while they were visiting the capital of Bosnia.

There is no indication in the article — nor on the editorial pages — to suggest that within a month their deaths would lead to countries across Europe taking up arms in a war that would continue for the next four years.

Bruce Tascona runs the Manitoba World War One Museum near La Riviere which, along with artifacts from the Great War, features recreations of the system of trenches used during the fighting. He says he read Free Press articles from that time to bolster his knowledge.

“As a historian, I always dip into the Free Press to see what is going on,” says Tascona, the author of nine local military history books.

Tascona says the newspaper has always done a “really good job” of covering the local military.

“Wherever there was a Manitoba slant to it, the Free Press covered it,” he says. “And, by the time of the First World War, the Free Press had built up a national reputation.”

Tascona says there was another element in Free Press coverage he appreciated.

“From a local historian viewpoint, there was always good local flavour — they didn’t just cover what came from the war office in Britain,” he says.

“Just go through the files — you’ll come to realize the military coverage was amazing.”

The first mention of the impending war on the paper’s editorial page appeared on July 30, 1914, under the appropriate headline The War.

Noting the different alliances connecting the nations, the editorial concluded, “Very plainly there are tremendous possibilities of warfare that might carve Europe more lastingly than the Napoleonic wars did, with a waste, suffering and demoralization which it would take the world long to recover from.”

When war did come — under the headline War news last night stirred all Winnipeg — the Aug. 5, 1914, story noted that “until long after midnight a mighty crowd, stirred to a pitch of delirious excitement by the fateful news, surged around the Free Press singing British patriotic airs and cheering with all the zest and abandon that their hoarse voices could command.

Free Press edition Aug. 5, 1914.

“Only for brief intervals, while the Free Press megaphone man announced some new sensation from the seat of war, was there a cessation of the pandemonium, but the mingled cheers and shouting that followed swelled forth in greater volume than ever.”

Retailers were quick to capitalize on the war frenzy. An ad for The Clothes Shop, at Portage Avenue and Carlton Street, announced that suits, hats and other items were “going at war scare prices.” Suits originally priced between $15 and $18 were marked down to $9.76. More expensive stock, previously $35, was tagged at $22.75.

“The die is cast. The Rubicon is passed. The British Empire, through no fault of her own, finds itself engaged in the most fateful war of the century. Upon the issue of the conflict depends the future of the Empire and the freedom of the world,” stated the Free Press editorial that day.

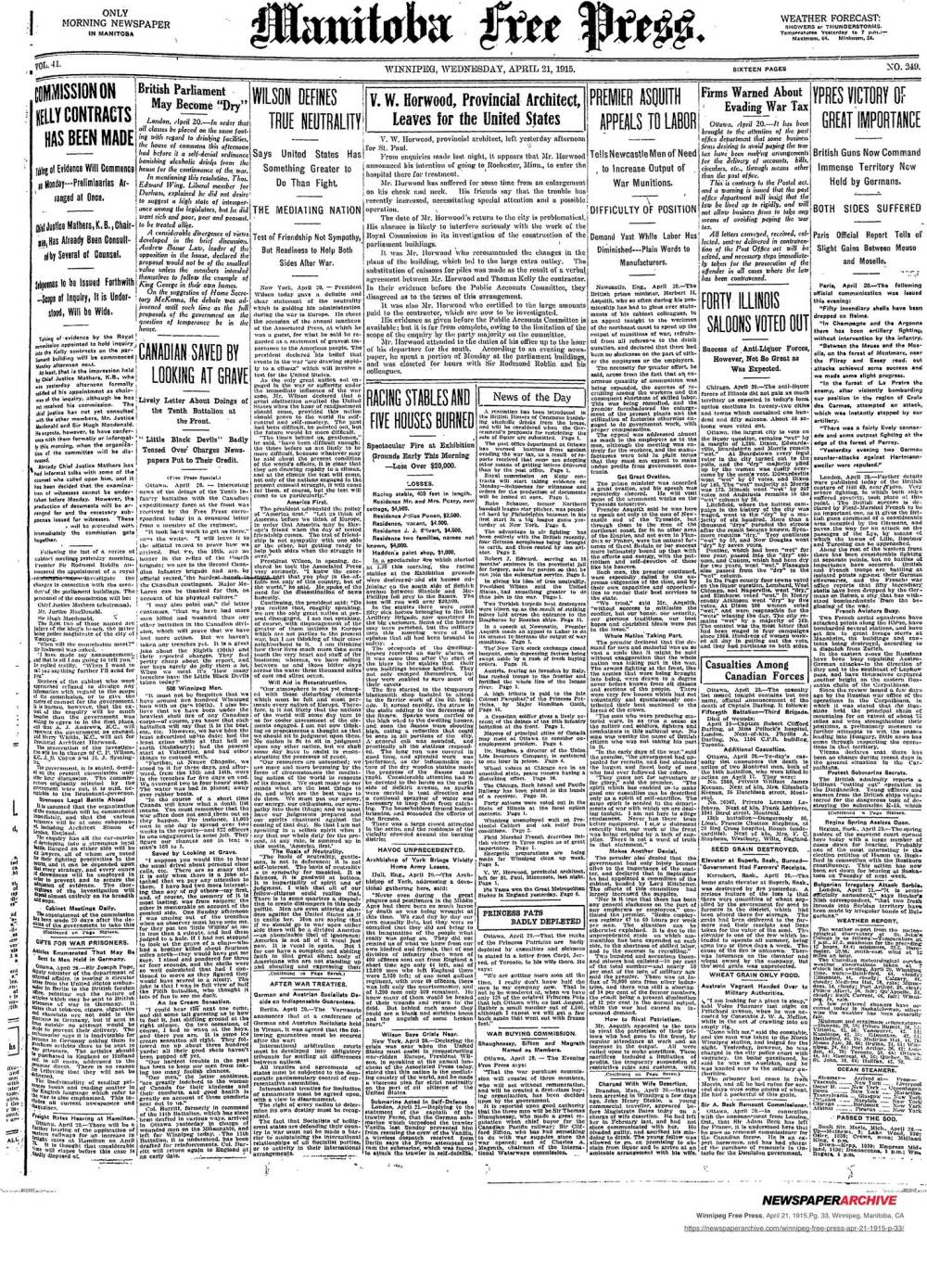

Free Press edition April 21, 1915.

The newspaper likely had an exclusive story on the front page April 21, 1915. An unnamed Free Press correspondent detailed a censored letter received from a soldier with the 10th Infantry Battalion at the front, offering a glimpse of the grim battlefield reality.

“In the course of a short time, Canada will know what a death list means. You must remember that the war office does not send these out as they happen. For instance, 11,000 men in one day is spread over two weeks in the reports — and 822 officers in one engagement is some jolt.”

The article quotes the soldier further, explaining how close he had been to joining that staggering number.

“If I had not stopped to look at a grave of a chap — who had a brother killed about 14 miles north — they would have got me sure. I stood and pondered for three or four seconds and the shells were so well calculated that, had I continue to move as they figured, they would have scored to a nicety.”

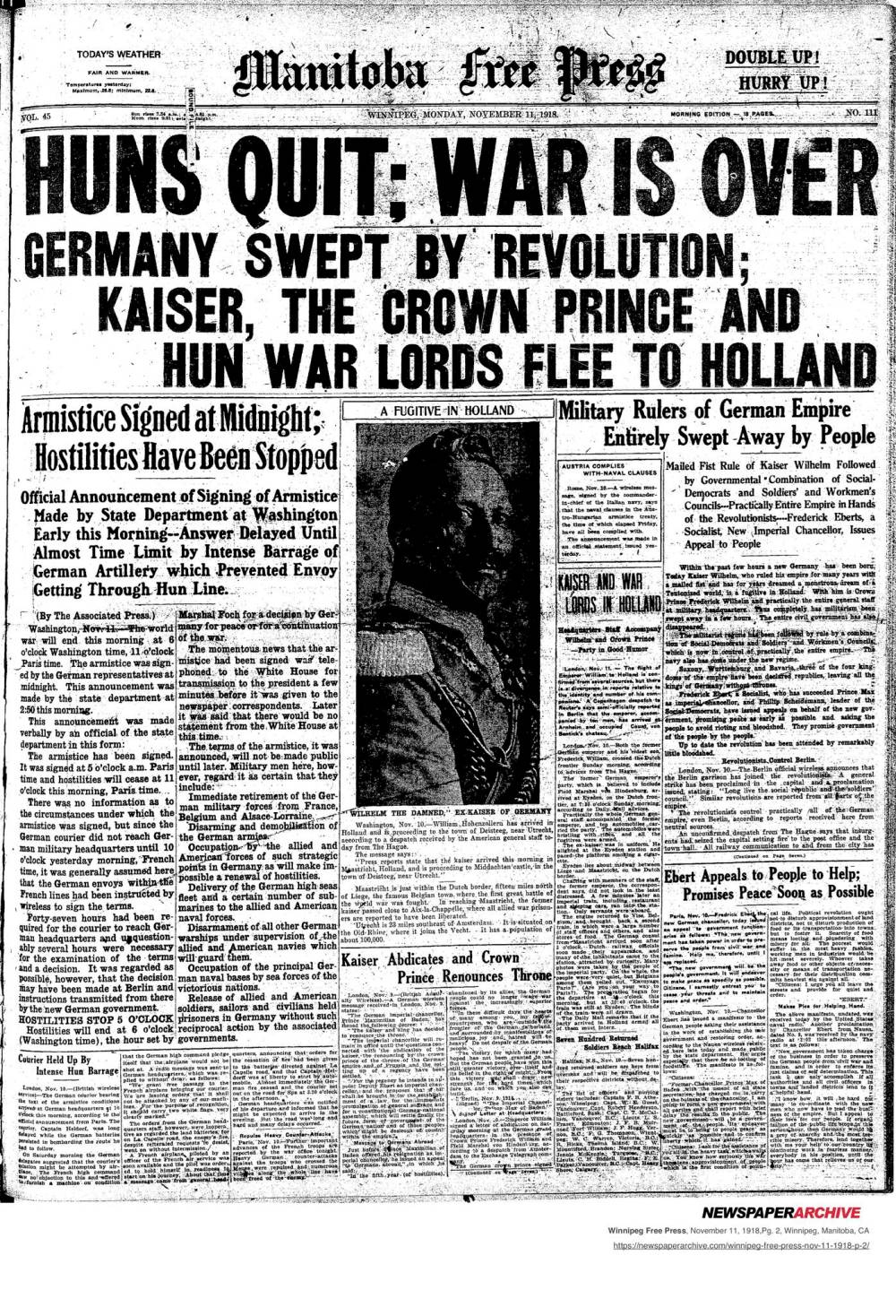

Free Press edition Nov. 11 1918.

On Nov. 11, 1918, Manitobans learned the Great War had ended.

But along with the many stories chronicling the elation of the day, there was an ominous headline on page 5: More nurses for Influenza patients supreme need of Winnipeg at present.

“Very, very many of the cases of extreme need of nursing are in the homes of soldiers’ families,” the article reported. “It will be a very sorry homecoming for men from overseas if they find the city and the country they risked their lives for has let their wives and families die for want of care while they were away.”

The seeds of another global conflict to come were evident on the front page of the Winnipeg Free Press on Jan. 31, 1933.

Free Press edition Jan. 31, 1933.

The catastrophic consequences of two front-page stories and a photo that day would be evident by the end of the decade: Hitler becomes new German chancellor; policies restricted, Japan likely to quit League, and Salute of fist and dagger, accompanied by an image of Italian premier Benito Mussolini.

The next day’s editorial page was silent on Hitler, but critical about the League of Nations’ (the forerunner to the United Nations) approach to Japan.

“Japan is busily engaged in acquiring an empire in Asia,” the editorial stated.

“The simple idea of throwing this aggressive, conquering nation out of its membership, and placarding it in the eyes of the world as an aggressor, an idea equal in simplicity to Japan’s own treatment of the situation, is evidently too much for the League’s mentality.”

On March 14, 1938, the Free Press announced, in a large front-page headline, Austria no longer a nation and had become part of Hitler’s Reich. One article reported that “Britain awoke this morning looking war straight in the eye.” Another said the first preparations were being made for war in Halifax since “the bugles sounded ceasefire 20 years ago.”

The Free Press editorial, next to a short one extolling the wonders of Walt Disney’s movie Snow White, predicted that Czechoslovakia was likely next on Germany’s list.

“If a disastrous train of events is lit by German aggression against this free, independent and war-like people, if France moves to Czech support, it would become difficult for Great Britain to stand aside, just as it became impossible for her to do so when Austria-Hungary marched against Serbia in July, 1914.

“The parallel between those events, and the events of the present, is painfully exact.”

There was optimism in some quarters that war had been averted a few months later. On Sept. 30, 1938, the Free Press published the headlines War fear ends as powers agree on progressive Czech cession and Europe’s millions greet settlement with ecstasy after Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany signed an agreement allowing Hitler’s forces to occupy the Sudeten areas of Czechoslovakia.

While British newspapers were unanimous in cheering prime minister Neville Chamberlain as a national hero for the “peace for our time” deal, a Free Press editorial was more skeptical, the headline asking, What’s the cheering for?

“While the cheers are proceeding over the success which is attending the project of dismembering a state by processes of bloodless aggression, some facts might be set out for the information of people who would like to know what the cheering is about and who ought to be taking part in it.

“The doctrine that Germany can intervene for racial reasons for the ‘protection’ of Germans on such grounds as she thinks proper in any country in the world which she is in a position to… and without regard to any engagements she has made or guarantees she has given, has now not only been asserted but made good; and it has been approved, sanctioned, certified and validated by the governments of Great Britain and France, who have undertaken in this respect to speak for the democracies of the world.

“This is the situation; and those who think it is all right will cheer for it.”

That analysis proved prescient less than a year later.

News of the German army’s attack on Poland made it into the final edition of the morning paper on Sept. 1, 1939. Both Britain and France issued ultimatums for the Germans to pull back.

Free Press edition Sept. 1, 1939.

Winnipeggers gathered outside the Free Press building on Carlton Street, where the latest headlines were posted.

“All night vigil was maintained by a crowd before the Free Press bulletin boards, a crowd numbering several hundred as late as 2 a.m., dwindling to a few score in the small hours, and only a dozen or do between 5 and 6 a.m.,” the paper reported.

“The big Free Press presses started rolling at 5:15 a.m., with the most fateful news in a decade. Copies of the first extra were snapped up like hot cakes in the first hour as newsboys cried the news in downtown streets.”

A large photograph on page 7 showed a Free Press employee, standing on a ladder outside the building, changing a large map of Europe to reflect the new developments.

“Hitler, having failed to get what he wanted out of Poland by threats, turned with lightning speed to force, stated the day’s editorial which bore the single-word headline: War.

“What has now happened to Poland has been long pre-destined. It was written in the fiery letters of the book of prophecy many years ago. Ever since the Nazi regime seized the reins of power in Germany in 1933, far-sighted men everywhere have known that, unless Hitler’s reckless course was stopped, no small nation in Europe was safe. Today not only the small nations are threatened.

“Today the shadow of disaster hangs over every nation in the world, great or small.”

There was no paper on Sunday, Sept. 3, when Great Britain and France declared war against Germany, but the next day’s Free Press reported France had put its full forces into action and was already shelling Germany, “to relieve German pressure on France’s eastern ally, Poland.”

The editorial headline that day was Canada is at war.

“This was inevitable from the moment that the ‘Peace Front’ was transferred by Nazi aggression into a War Front for the defence of the liberties of mankind.”

On Sept. 18, the prediction made by the editorial board three weeks earlier came to fruition: Soviet Russian troops surged into eastern Poland on a 800-kilometre front.

By Dec. 9, 1941, the fate of Manitobans serving in the Winnipeg Grenadiers regiment in Hong Kong was uppermost in the minds of many at home when the news broke that Japanese forces had attacked what was known as the “British citadel of defence in the Far East” just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Free Press edition Dec. 8, 1941.

The Manitoba soldiers, the article noted, had arrived less than a month before. A cable sent from Hong Kong by Sgt. Robert Manchester to his wife at 725 Sherbrook St., reported, “All well and safe. Keep smiling.” He had been part of a Manitoba unit that had landed there on Nov. 16 as part of the large Canadian force.

Just over two weeks later, on Boxing Day, the Free Press announced Hong Kong surrenders. Unfortunately, for anxious families here, details were in short supply.

“The news of Hong Kong is hard to take, especially here in our own province of Manitoba which has suffered a blow of a magnitude unequalled in its tragedy and severity,” said the day’s editorial.

“Hundreds of homes in Winnipeg and in the country have been thrown into great anxiety after weeks of strain which has tested their courage and endurance to the limit. In spite of the steadily lengthening lists of Air Force casualties, we have been lightly dealt with during these first two years of war. Now, alas, in the grim phrase of John Bright: the Angel of Death is abroad in the land. You can almost hear the flutter of his wings.”

The editorial went on to say that questions about whether it had been a mistake to send troops would have to wait until the war’s end for an answer.

The United States was forced to become involved after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. But, while the surprise assault on the American naval base in Hawaii shocked people around the world and killed 1,500 servicemen, the Free Press predicted the next day that it marked the beginning of the end for the war.

“Long though the struggle may be and desperate its course, the final outcome of the war no longer remains in any doubt. Hitler and his wretched satellites in Europe — upon three of whom Canada declared war on Saturday night — and the crazed war-lords of Japan have brought doom upon themselves which they cannot escape. It is now war to the bitter end,” stated the editorial.

“The free world stands shoulder to shoulder, armed and fighting, against the black and evil forces that have risen from the pit to persecute and destroy the hopes and aspirations of free, peaceful, law-abiding, decent men and women the world over.”

Through the early months of the war the Free Press published long, detailed histories of four local regiments in its magazine section written by local lawyer Roy St. George Stubbs.

Stubbs, who had worked at the Winnipeg Tribune before passing the bar, served with the RCAF during the war. Prior to enlisting, he freelanced the histories of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and the Winnipeg Light Infantry to the Free Press.

He later turned the articles into a book that a Free Press reviewer said “will find a place in the library of every military man and should be just as eagerly read by those who have pride in their heritage of Canada and particularly of Manitoba.”

In addition to providing news from overseas, the newspaper made sure to report on the losses experienced by the families of Winnipeg and Manitoba soldiers.

Each day, most often under the headline, Latest army casualty list, the paper published the names of killed and injured soldiers accompanied, whenever possible, by a photograph.

“The Free Press would scramble to get photos and information on these people,” Tascona says.

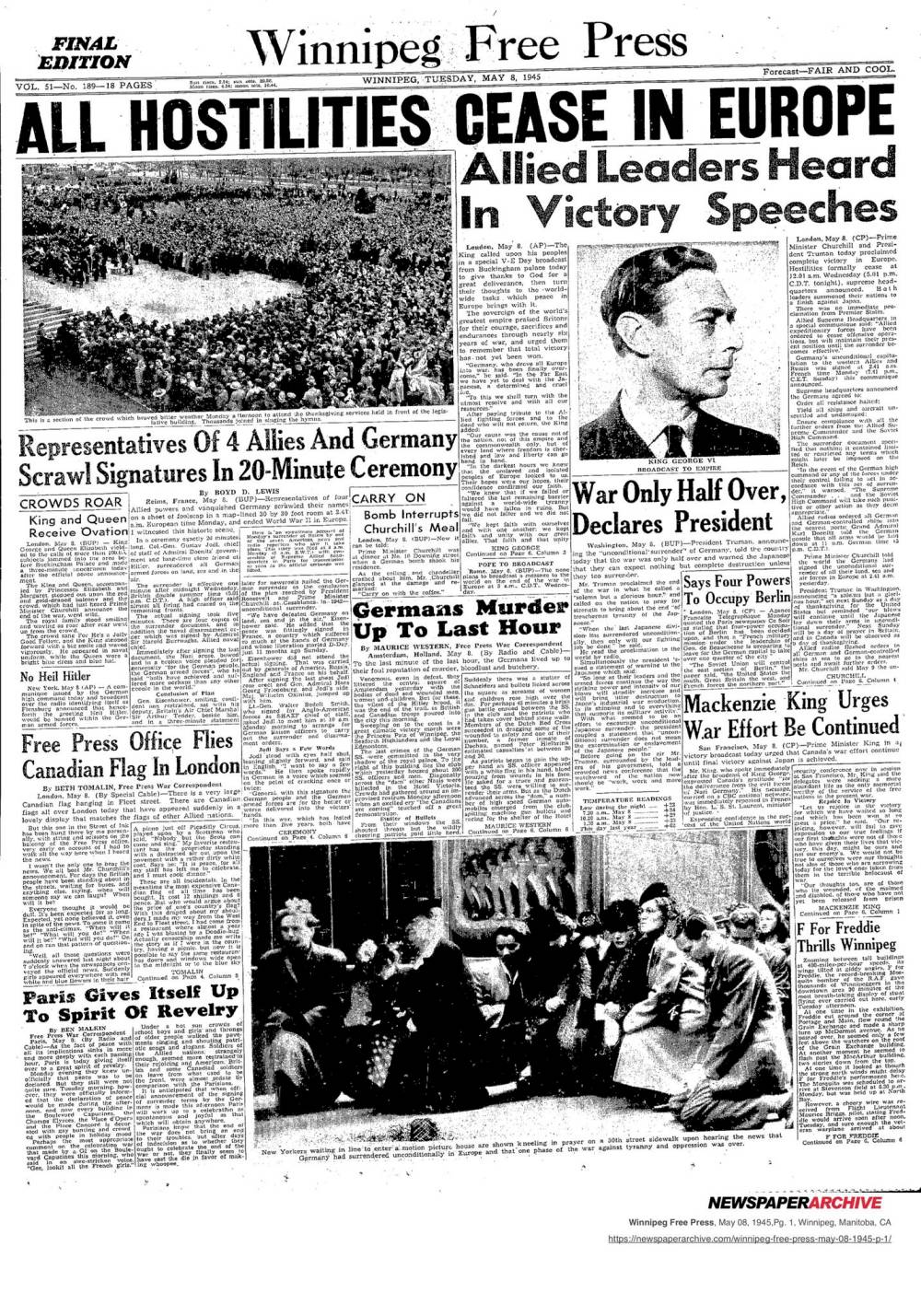

Free Press edition May 8, 1945.

Such was the case on Jan. 20, 1945; the Free Press reported nine Manitobans on the army’s 775th casualty list, released during the war by the federal government. The dead included Gunner John Pert, son of Mrs. H. Pert, of 150 Rupert Ave., who was born and educated in Winnipeg. Under the heading Slightly injured was the name of Sgt. Edward S. Lovelace, son of Mr. and Mrs. S. Lovelace of 696 Home St.

Photographs of Pert and Lovelace appeared next to the lengthy list, which also included the names of killed and wounded soldiers from across the country.

Towards the end of the war, the Free Press published a series of articles under the title “Women War Workers” featuring the people who stepped up to help employers who were left short-handed when men went overseas to fight.

The series also touched on the possibility of the women continuing in the jobs after the war.

The Jan. 20, 1945 article, by Mary Gustafson, looked at the future of “postal girls.” The assistant superintendent of mail, J. Bowie, was quoted as saying the Crown corporation would be surveying different provinces “and (the women) will all be taken into consideration before a definite answer will be given.”

There were between 50 to 60 women working in Winnipeg’s main post office at the time.

“The girls have become as efficient as the men and the supervisors have all obtained a very favourable impression,” the story said. “However, the only reply to how they compared with the men was — When they’re good, they’re very, very good. But when they’re bad, they’re very, very bad.”

None of the replacement workers were quoted in the article, which stated, “The main opinion among the girls seems to be a great liking for their job, but those who weren’t married said that if given a choice there would be no doubt as to which course they would take — marriage.”

Shortly before the fighting ended in Europe, a note on the April 30, 1945 front page let readers know there would be no extra issue announcing it was over, because of “the stringent shortage of newsprint.”

“Attention will be concentrated upon providing readers with the best possible service in both news and comment, in its regular editions at their regular hours.”

On Aug. 8, two days after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, the Free Press editorial said, “There will be general satisfaction in the discovery of a secret weapon which will hasten the end of the war.”

“But there can be no ultimate gain to humanity from the forging of this terrible weapon except this: it may shock the civilized world into banishing forever the insanity of war.”

The war ended on Aug. 14.

The next day, a Free Press story said “none of us in Manitoba will ever forget that terrible Christmas for our heart was in Hong Kong with our Grenadiers and parts of our heart have been there with them ever since.”

Another article, about the wives and families of members of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, said they were “torn between sheer gladness and concern over the waiting period before they can hope to see their loved ones.”

A story inside the paper headlined Winnipeg rejoices, described one “blissful sailor sporting several lipstick trademarks” saying, “This is the kind of night I’ve dreamed of.”

Nearby, two women had the initials V-J (Victory Japan) marked with lipstick on their foreheads.

Mayor Garnet Coulter declared the next day a civic holiday. The newspaper noted that even though it was a holiday, liquor stores would be open.

A full-page Hudson’s Bay advertisement was taken up entirely by the Lord’s Prayer, with a small note at the bottom informing customers the store would be closed for two days.

And the editorial, under the headline Peace with victory, asked “was the price too great?

“How easy for stay-at-homes to say that it was not. How hard for those who themselves have suffered, and for those who served, to answer yes. But it will be the answer of history that the free world met its most cruel dilemma firmly, that it did not falter, that it reached its goal.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.