Growing up Geekie Athletic excellence in the genes of Strathclair family

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/09/2021 (1652 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

STRATHCLAIR — It’s a hot day in August and the Geekie brothers are home together for a change.

That doesn’t happen much anymore.

Morgan, the eldest, has packed a lot into summer. After playing 36 games for the Carolina Hurricanes last season, the 23-year-old centre was chosen by the Seattle Kraken in the NHL expansion draft.

Less than two weeks later, he married his high-school sweetheart, Emma Coulter.

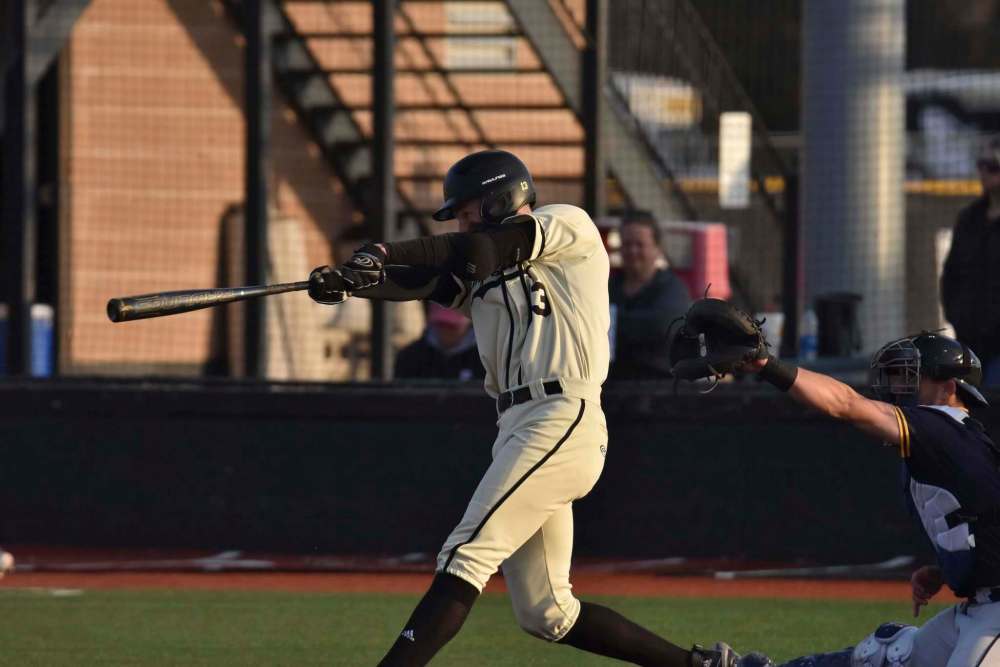

Noah, the middle son of Craig and Tobi Geekie, will leave shortly for his second year of college baseball at Emporia State University in Emporia, Kan., where he’s an outfielder for the NCAA Division II Hornets.

And then there’s Conor, the youngest and tallest of the trio, who’s preparing for his second full season as a member the WHL’s Winnipeg Ice. The biggest personality in the bunch, Conor is likely a first-round pick in the 2022 NHL Draft.

The concentration of athletic talent emerging from one house in tiny Strathclair (pop. 709) — about 95 km northwest of Brandon — begs the question: how and why did this happen?

Everyone has a theory. There’s the talent angle, surely. Craig was an accomplished baseball player and WHLer during the 1990s, and Tobi’s childhood was filled with a love of sports that she passed on to her kids.

Parenting style appears to be a big part of it, too.

“They just wanted us to do what we loved,” says Noah, 21. “They didn’t care whether it was baseball or hockey or playing a piano or whatever — they were by our sides every step of the way. And they were going to support us whatever path we chose, so I think that was a big part of it.

“Because… growing up, it wasn’t like, ‘Oh, we have to play hockey or we have to play hockey year round and go to workouts in the summers and play summer hockey and all that.’ We played multiple sports and we loved doing it. They loved taking us on the road.”

In an era when youth sports is heavily regimented and over-managed, the Geekies took the opposite tack, giving their boys freedom to roam. Whether that meant informal games on their spacious yard or an abundance of athletic options.

“We never pushed a thing,” says Craig, 48. “We’ve never told them to go to practice or go outside and throw a ball. We’ve never done any of that. I mean, that might be the perception… but anybody that’s close to us knows that if you came over on a normal day, they’d probably be playing catch or playing football or playing ladder golf or something.”

Emma Geekie, originally from Hamiota, played atom and peewee hockey with her future husband on Yellowhead teams between the ages of 11 and 13. She says the testosterone-drenched atmosphere at Chez Geekie takes some getting used to.

“It’s very competitive, very loud,” says Emma, who recently graduated with a nursing degree from the University of Regina. “They always have to be doing something. They couldn’t sit still. Even now, they can’t sit still.”

Follow the leader

In his early years, Morgan looked to his dad for guidance on the baseball diamond and at the hockey rink. Craig’s penetrating stare was a constant presence behind the bench — he coached all three boys at various times.

“I think he gets a bad rep for being no-nonsense,” says Morgan. “He probably looks intimidating… a lot of my friends have said that he’s maybe a little intimidating and I’m sure he can be. I remember being younger, he definitely was. But all he expects is just for us to work hard — that’s literally all he expects. If it doesn’t go to plan and you work hard, then he doesn’t care and he’s probably like the most fun to be around out of all of us, because he’s very outgoing. You see a little bit of him in all of us.”

Craig’s own hockey career probably factors heavily into his coaching style. A defenceman on a Brandon Wheat Kings team that finished dead last in the WHL with 28 points in 1991-92, he was also a key performer on the Brandon team that was 62 points better a year later.

It’s a Canadian major-junior record that still stands.

“I’m in awe of Craig and even my kids because they have that knack, right?” says Tobi of her husband’s communications skills. “The kids listen to Craig. I can run the same practice as Craig tries to run… I’ve coached and I try to do the same thing and say the same things and nobody listens. Everybody wants to know what he does because kids are just tuned in when Craig speaks.”

Morgan is in his comfort zone. Now 6-2 and 195 pounds, he’s a far cry from the 150-pounder who made a permanent jump to the WHL’s Tri-City Americans as a 17-year-old.

From the beginning, the family was not inclined to rush him. After being drafted by Tri-City, he skipped his first WHL training camp in order to represent Manitoba at the baseball age-group nationals. A year later, Craig decided it was in Morgan’s best interest to play at home rather than remain in the WHL.

Merely good as a rookie, Morgan was bypassed in the NHL Draft but broke out as an 18-year-old, piling up 90 points in 72 games while playing on a line with future NHL first-rounder Michael Rasmussen.

“The (Geekies) are good people and the process was great. Morgan was a big, big part of some very good teams here and just continued to develop, year after year,” says Americans general manager Bob Tory.

There’s been steady improvement since. Drafted in the third round by the Hurricanes in 2017, he played on Carolina’s Calder Cup-winning American Hockey League affiliate in 2018-19 and made a stunning NHL debut with two goals and an assist in his first game. He carved out a more permanent spot on a talent-rich Hurricanes squad during the 2021 season.

He views a fresh start with the Kraken in purely positive terms.

“I think it’s sunk in a little more now because it’s like kind of like being traded,” he says. “I’ve only ever played for one team in every league growing up, so it’ll be different, I think. But other than that, it’s good. It’s a great organization. The ownership group’s great, everything’s looking positive. I’m just looking forward to it — there’ll be a lot of opportunity.”

Although the brothers will be scattered around North America during the baseball and hockey seasons, they will be in daily contact, usually chirping each other via FaceTime. It stokes the natural competitive fire the brothers share.

“A lot of people think that we were kind of like pushed into playing sports,” says Morgan. “(Mom and dad) definitely supported us and everything, but I think a lot of it was just we want to be better than our brothers. We want to beat each other outside, and I think that’s what contributed to it and we wanted the better stories when you came home.”

“I always tell people they are each other’s best friends and I mean that wholeheartedly,” says Tobi. “I think the three of them talk to each other every day as busy as their lives are. And we very rarely had to split up any sort of fights with them. They’d figure it out on their own.”

For the love of the game

For Noah, the choice between baseball and hockey was difficult. For those who know him best, however, his decision to go the baseball route was no surprise.

A second-round selection of the Calgary Hitmen in the 2015 WHL Draft, he also played on Manitoba’s silver-medal-winning baseball team at the 2017 Canada Summer Games and left home to play at Okotoks (Alta.) Baseball Academy before transitioning to Barton Community College in Great Bend, Kan. After two years at Barton, the 6-3, 195-pound outfielder/left-handed pitcher was recruited to play for ESU.

He may not earn a fortune like his hockey-playing brothers, but he wants to continue to play and then give back to the sport as a coach.

“(I want to play) as long as I can — wherever that takes me,” says Noah. “I’ve got two more years at Emporia State… so two more years of that and, hopefully, I can find a professional spot somewhere in an independent league. I just want to keep playing as long as I can.”

Derek Shamray has coached all three boys in baseball and Morgan in hockey, and he’s witnessed success at every level.

“They’re all very committed,” says Shamray. “It starts with Craig and Tobi. (The boys) are very good (athletes) naturally, but the commitment level they have sets them apart. You can have as much natural talent as you want but if you don’t commit yourself, you’re not going to go anywhere.”

Young and restless

Conor,17, has made a career out of trying to keep up with his brothers. Now, he’s starting to make a big name for himself.

A point-per-game player as a 16-year-old in the Regina hub last spring, the 6-4, 205-pounder has developed a combination of skill and abrasiveness that has scouts raving about his pro potential.

But he says he is nothing without Noah and Morgan.

“Without them I wouldn’t be the player I am today,” says Conor. “I’m super competitive. I’m not a very good loser and I’ll do anything it takes to win and I think growing up against them, I was just trying to play as hard as I could. I’m six years younger than Morgan and four years younger than Noah, so I got to try and hold my ground… I know a lot of brothers don’t let the younger siblings play but they always put me on a team somewhere.”

This summer, Manitoba’s former U15 baseball player of the year devoted much of his time to the ice, participating in agent Kevin Epp’s training camp as well as Team Canada’s U18 evaluation camp in Calgary.

The accolades are fine, Conor says, but he’s aware of the humility his brothers display.

“What they’re really good at is never letting the game take over their lives, right?” says Conor. “I mean, you just look how they carry themselves and they look like they don’t even play the sport, honestly. It’s like they’re just normal human beings, and I think that’s what I’m trying to grow up as.”

mike.sawatzky@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @sawa1

Variety keeps kids active in the game

Encouraging kids to participate in a wide range of sports makes good sense. Trying to explain that concept to a hockey-mad parent with designs on developing a future NHL star is a more complex argument.

Craig and Tobi Geekie are parents who subscribe to the former model. They allowed their sons Morgan, Noah and Conor to sample widely. For the brothers, fun was foremost.

Steve Norris, CEO of Calgary’s WinSport Winter Sport Institute, says the key to having children enjoy athletic competition does not come from providing adults with entertainment.

“It comes from within,” says Norris. “They’ve not been beaten to a pulp on the journey and actually start to not dislike what they’re doing and no longer having fun. Remember, all the research in North America shows the No. 1 reason why kids play sports is having fun and the No. 1 reason they drop out or leave sport is not having fun. And understand that what is fun for an eight-year-old is vastly different than a 16-year-old or a 24-year-old, even if they’re doing the same activities.”

Norris believes exposure to a variety of sports has a positive impact that far outweighs any benefits of dedicated practise in one sport from an early age.

“There is a fundamental physical literacy, which is no different, if you like, than academic literacy,” says Norris. “The fundamental basics: the ability to run, jump, throw change direction, understand pressure sensitivity, like for edging (while skating) or whatever it might be. Rhythm is so important… many of these things that are laid down certainly in the first decade of life.”

Baseball and hockey, for instance, might look different but actually complement each other.

“There are transferable skills, we know this in all walks of life,” says Norris, who has served as a consultant for Hockey Canada and as the lead sports physiologist and strategic planner for Canada’s winter Olympic sports.

“By the time you take into account hand-eye co-ordination, the rhythm and the movement and the ability to understand where you are in space and time, the ability to change direction, the ability to accelerate, your ability to have some kind of endurance, no matter what the sport is… (helps to develop) the ability to do these things and the ability to have a brain that can actually read the game.”

Norris suggests Canada has wasted its competitive advantage in hockey by failing to keep kids engaged in the game.

“We artificially select these kids very early in life — so here we have around over 500,000 registered players in minor hockey in Canada; around the same as in the United States — but by the time we get to about 13, 14 years of age and above and get to the sort of real infiltration of AAA hockey, we reduce ourselves to the size of Sweden and Finland. One of our major advantages are population size and population engagement in hockey and we eradicate it.”

— Mike Sawatzky