Driven by dreams, trapped in nightmares Players describe an unravelling Broncos dressing room, reveal emotional scars decades later

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/12/2020 (1911 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Twenty-five games into the Swift Current Broncos’ 1993-94 season, Darren McLean had reached his breaking point.

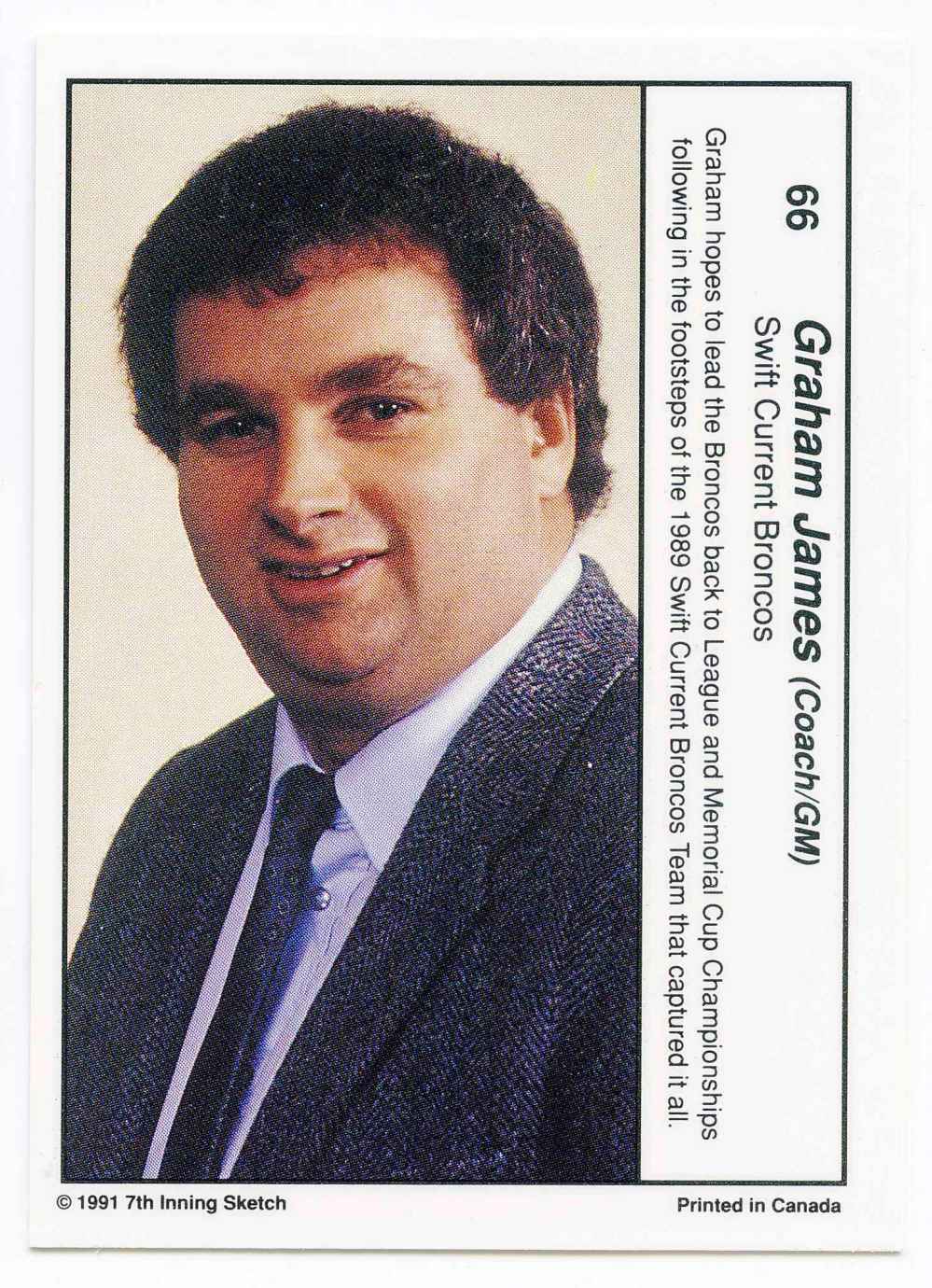

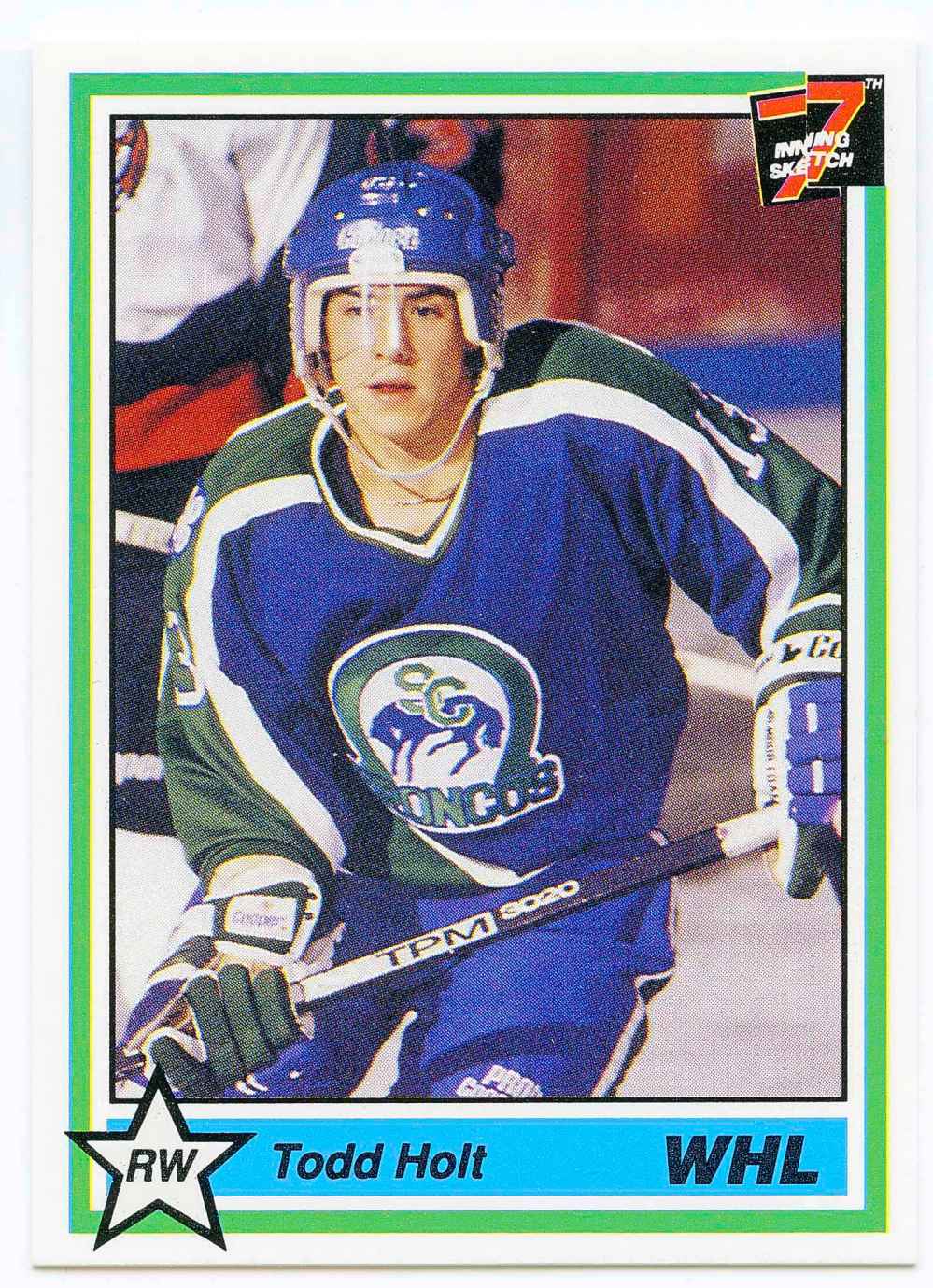

Days earlier, star forward Todd Holt had revealed a litany of horrors that he endured for years at the hands of their coach, Graham James.

The two players, who had been friends since playing minor hockey together in Estevan, Sask., were rooming together for the first time on a Broncos road trip.

About this series

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

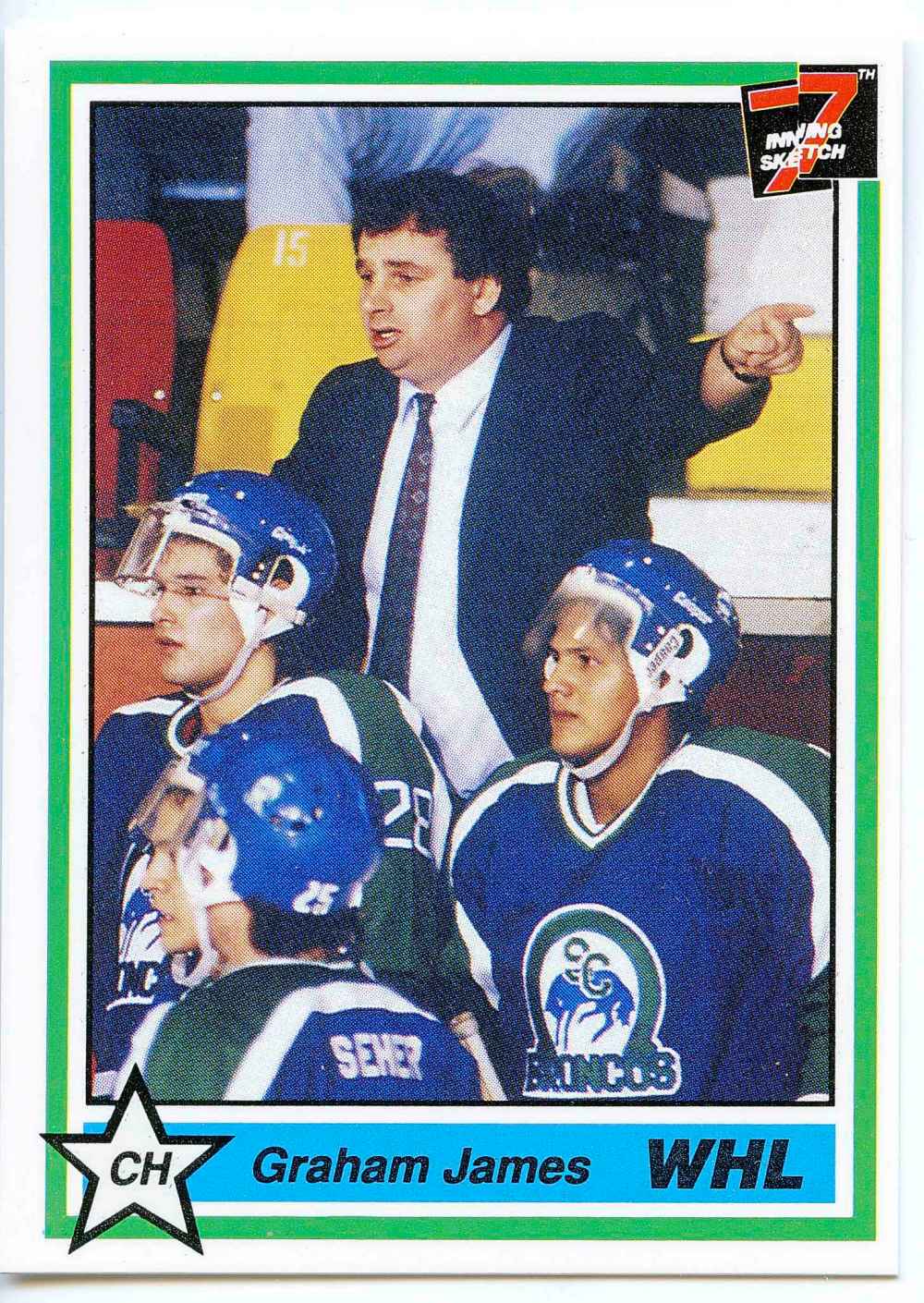

While a significant number of the assaults occurred in Saskatchewan, where he coached both the Western Hockey League’s Moose Jaw Warriors and Swift Current Broncos, the James scandal has always been a Winnipeg story.

James worked his way up through the ranks here — in Winnipeg minor hockey, the Manitoba Junior Hockey League and the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors.

It was with this backdrop that Free Press sports writer Jeff Hamilton began investigating James’ past, from his formative years growing up as an Air Force brat in St. James to his time as a substitute teacher in the St. James-Assiniboia School Division, and from his first foray into coaching minor hockey to his ultimate downfall.

Hamilton interviewed dozens of former players, childhood friends, educators and hockey colleagues and officials.

His investigation reveals an awkward teen who found confidence both in the classroom and at the rink, one that enabled him to embark on his trail of destructive criminal behaviour.

The investigation also paints a picture of complicity or, at the very least, wilful ignorance through all levels of the sport, which allowed James to abuse young players for years.

In total, James has been convicted of sexually assaulting five former players: Sheldon Kennedy, Theoren Fleury and Todd Holt have all publicly shared their ordeals; the identities of two others have been protected by publication bans.

However, police estimate the true number of victims is between 25 and 100.

While powerful institutions, such as the Catholic Church, and prominent individuals, including Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, have all had their moments of reckoning, there has been no equivalent to the #MeToo movement in hockey.

This Free Press investigation attempts to change that narrative by giving voice to victims and asking questions of those who knew or ought to have known what was happening on their watch.

Read the full six-part series, titled A Stain on Our Game.

After a night of heavy drinking, Holt summoned the courage to tell McLean a dark, twisted secret: James was terrorizing him behind closed doors, abusing him multiple times each week.

McLean, in his second season with the Broncos had, until that point, thought that if anything was going on between the two it could be consensual. Holt had spent a lot of time with James, was living at his house and used to spend meals with the coach while the rest of the team ate in a separate part of the restaurant.

McLean lay in his bed haunted by what he just heard.

“That was the very first minute I knew Graham James was a predator,” he says. “That dissolved my soul for hockey. It was a real defining moment for me.”

Fed up with James and tired of watching his teammates walk around like zombies, McLean went to team captain Rick Girard and a few other veteran players.

After weeks of McLean’s persistence, they in turn approached assistant general manager Doug Mosher and threatened to quit unless the team’s management fired their coach; a coach who was considered godlike in the small Saskatchewan city after guiding the Broncos from a tragic December 1986 bus crash that killed four players in his first season to Memorial Cup champions just 2 1/2 seasons later.

Was James’ time terrorizing teenage boys finally coming to an end? Part 4 of a Free Press investigation goes inside an unravelling Broncos’ dressing room.

● ● ●

The Parole Board of Canada granted James full parole in September 2016.

James, then 64, still had prison time on the books for hundreds of incidents of sexual abuse against former players Holt and Holt’s cousin Theoren Fleury, plus a two-year sentence from 2015 that had yet to begin for activities involving an unnamed Bronco.

James had already finished a sentence of 3 1/2 years, beginning in 1997, for similar crimes against Sheldon Kennedy and one other unnamed player — plus an additional six months, served concurrently, for an indecent assault on a 14-year-old boy in 1971 when James was 19.

In the parole board’s written statement, it noted James had admitted to having “sexual intercourse with around 20 hockey players he was coaching,” though police believe there are as many as 100 victims.

“The physical and psychological harm caused to the victims is undeniable,” the report states. “You were using manipulation, control and your position of trust and authority to facilitate the assaults.”

Since getting full parole, James has reconnected with a few old friends, most of whom he met through hockey and who remained supportive, albeit silently, during his time behind bars. But he has little to do with his immediate family, other than maintaining a relationship with his elderly father.

Rusty James, who is nine years younger than his brother, can’t remember the last time they spoke.

He no longer tries to make sense of the path his brother chose, as much as it haunts him.

“It’s an incomprehensible break of trust.”

“It’s an incomprehensible break of trust,” Rusty says during a two-hour phone interview from his home in Buffalo, N.Y.

He falls silent for a moment before continuing.

“Maybe I’m not accepting whatever illness or whatever problems he had and maybe it’s bad on me in that sense. But he was just too smart of a person to allow this to happen and that’s probably the biggest thing I can’t get over. I just…”

Another pause.

“I can’t.”

After an unremarkable hockey career as a goaltender, Rusty moved on to coaching, including several bantam and midget AAA teams in Nova Scotia. The two brothers went into business together in the mid-1990s, and when James left Swift Current to start up a new WHL club, the Calgary Hitmen, he named Rusty his assistant general manager.

“We were close. He was my big brother. Even though we didn’t grow up together we got into business together and there was a whole lot of stuff that went on with that, like a loss of money. But I don’t even think about that,” he says. “It is what it is, I guess.”

Rusty didn’t know his brother was gay, let alone a sexual predator. Looking back, he can recall a few instances where James could have been hinting at being gay, but insists it wasn’t as obvious as others might suggest.

Hindsight has also changed the way he feels about the close relationships James fostered with his players, something he says seemed so innocent back then.

“I just thought it was Graham filling a void and helping these guys be better people and better players”

Never could he have imagined the kind of trauma his brother was inflicting on them.

“I know how many of those individuals… had a broken-down home situation and they needed someone to lean on and they needed that trust,” Rusty says, adding that he got to know most of the victims, making it that much harder to comprehend the abuse.

“I just thought it was Graham filling a void and helping these guys be better people and better players, ultimately.”

What also pained him was the finger-pointing by the media and the general public. Rusty was one of several people with close ties to James who were condemned for not knowing more or — as was often the case — anything at all.

Rusty reinforces that in a text message: “I believe pretty strongly that Graham acted alone. I believe some knew he was gay. But in the private-weaved world that he lived, he carefully acted alone, which is why he was able to abuse for so long. His ‘private world.’”

”In the private-weaved world that he lived, he carefully acted alone, which is why he was able to abuse for so long.”

Many have questioned why so few people, over multiple stops along Graham James’ coaching career — Winnipeg, Moose Jaw, Swift Current and finally Calgary — had little to no idea of what was going on.

All the while, rumours and innuendo flowed freely among players that James was sexually involved with some of the teenage boys he was coaching.

It had become the accepted narrative that he was able to abuse his victims — committing hundreds of acts of sexual assault — undetected. But he wasn’t always flying under the radar.

As time went on, his actions became more reckless. But instead of confronting an ugly truth, team and league executives chose to turn their backs on evidence that there was something rotten about junior hockey in Swift Current, a rot that allowed a predator to do as he pleased for years.

● ● ●

It’s 1983 and 14-year-old Sheldon Kennedy wakes up every morning and goes to bed every night dreaming of playing in the National Hockey League.

The skinny, smooth-skating forward from the tiny western Manitoba town of Elkhorn knows it’s a long shot. But like most kids growing up in the heart of the Canadian Prairies, he’s willing to sacrifice everything to get there. Having come from an unstable home, a professional hockey career offers more than stardom — it’s a ticket to a better life.

With time still to grow into his body, he already possesses world-class speed and displays the kind of hockey smarts that can’t often be taught.

More importantly, Kennedy has someone in his corner who seems committed to helping him get to hockey’s biggest stage.

Graham James saw enough in Kennedy at a hockey camp in Brandon a year earlier to believe he could play in the Western Hockey League — a feeder league to the NHL. At least that’s what James tells Kennedy’s parents when trying to convince them to ship their son to Winnipeg to take part in a hockey tournament showcasing the province’s top talent.

To sweeten the deal for the cash-strapped family, James offers to host Kennedy in his one-bedroom apartment. It seems like a dream come true to have a supporter like James, who is deeply connected within the game.

James is fresh off leading the Fort Garry Blues of the Manitoba Junior Hockey League to their first championship in 25 years and, after working for multiple teams in the WHL, has cemented his first full-time job in the league as the head scout of the now-defunct Winnipeg Warriors.

“My mom and dad couldn’t put me on a bus fast enough,” Kennedy tells the Free Press 3 1/2 decades later.

That bus trip was the start of a never-ending journey into hell.

“I had gone to Winnipeg as a goofy, slightly mixed-up kid dreaming about the future and came back as a zombie.”

“I had gone to Winnipeg as a goofy, slightly mixed-up kid dreaming about the future and came back as a zombie,” Kennedy wrote in his 2006 book Why I didn’t Say Anything.

“Nothing in my experience could have prepared me to understand the abuse or the terrible emotions it left in its wake.”

Only hours into his first night in Winnipeg, Kennedy lay silently in the dark as James moved his hands up and down his body. James, who was in his early 30s, had spent the previous couple hours breaking down the young teen, who had been provided a cot next to his bed.

Kennedy had found it odd at first that James covered his apartment windows with cardboard to prevent light from peeking through. But now, as James tried to fondle him, it was all Kennedy could think about. He knew he was in trouble.

At first, James tried to run his hand up Kennedy’s leg, only to be brushed away. Taking a more aggressive approach, James turned on the lights so that Kennedy could see him cradling a shotgun he grabbed from a closet.

With the lights turned off again and Kennedy shaking underneath the covers, James pulled down his boxers and placed his mouth around Kennedy’s penis. Kennedy was no longer capable of fighting back.

James, in a final act of sexual aggression, stood over his prey and masturbated on Kennedy’s feet.

It was the first of 300 assaults on Kennedy, who would be coached by James the remainder of his junior career, escaping only after he turned pro.

“The next morning, he acted as if everything was normal between us, that this kind of stuff happened all the time and wasn’t really worth talking about,” Kennedy says.

●●●

Of all James’ former players who have come forward, Kennedy has been the most public.

He would reach his dream, moving on to an NHL career that included stops in Detroit, Calgary and Boston. His rights were also briefly held by the Winnipeg Jets.

And like NHL superstar Fleury — the most famous among James’ victims — it wouldn’t be until years after the abuse stopped that he would break his silence. Kennedy was the first to report James to police, in 1996. Fleury and Holt stepped forward in 2010.

But it’s what Kennedy has done since that he will be remembered for most.

He has dedicated his life to preventing others from experiencing the same horrors he went through. He attends numerous speaking engagements every year — an evolution that began almost exclusively with sharing his own personal story, to now talking about the red flags and devastating effects of child abuse and advocating for policy change from various levels of government.

Just recently, he moved on from his role with the Sheldon Kennedy Advocacy Centre in Calgary (the name of the centre has since changed).

Kennedy remains fully committed to his company, Respect Group Inc., which he founded in 2004 with friend and business partner Wayne McNeil. Respect Group Inc. is aimed at empowering people to recognize and prevent bullying, abuse, harassment and discrimination through online training courses. It covers all industries where abuse could be prevalent, including sports and at the workplace, with a specific focus on the school system.

What also differentiates Kennedy’s experience from that of other victims is how long the abuse lasted and the level of obsession James had for him; an intense infatuation with Kennedy that deepened over time.

“I do believe that Sheldon’s case was the worst case of them all because, when reflecting back, I know how long that timeline was,” Rusty James says.

Dr. Joe Sullivan, a prominent forensic psychologist based in Ireland who has worked closely with U.K. law enforcement to help investigate, detect and prosecute sexual predators, says the James case is a classic example of the three paths a predator embarks on to groom his victims.

The first is to manipulate the perceptions of the child but also others who might have a vested interest in protecting them. The second is to prevent suspicion. disclosure or discovery of the abuse. Finally, the third is to create the opportunity to engage in sexual activity with the child.

”The way they can keep the child on board is to continue to dangle the prospect of achieving their goal in front of them.”

“A child who dreams of being a hockey player in the NHL, they will automatically be drawn to powerful, influential people who are offering to help or support them in achieving their goal,” Sullivan says in a Skype interview.

“Once they’ve created this image of themselves to being the conduit to this dream they have, they can just sit back and wait for the children to come to them. The way they can keep the child on board is to continue to dangle the prospect of achieving their goal in front of them.”

James would have known he was sexually interested in young males by as early as age 11, Sullivan says, based on his experience speaking with offenders. By 17 or 18, Sullivan figures James would already have been sexually exploiting and abusing younger children than himself and that this behaviour would have evolved over time.

“The abuse that he first gets caught for is very unlikely to be the start and end of his abuse. It’s likely to be much more significant than that,” he says.

“The abuse that he first gets caught for is very unlikely to be the start and end of his abuse.”

“He has been refining those skills so that when he meets, say, Sheldon, for example, he’s developed quite an expertise in spotting vulnerabilities and playing to the vulnerabilities, working out quickly what are the vulnerabilities in a child’s life and pressing those buttons to get what he wants, which is sort of an exclusive, dependent relationship where he can go on and exploit.”

It’s taken years of working with therapists, but Kennedy is at peace with his personal life. He’s in his second marriage and his days are busy tending to a young toddler. He maintains a healthy relationship with his ex-wife and continues to strive to be the best father he can to his adult daughter, Ryan.

Though he’s made notable strides in his healing, Kennedy struggles to understand how no one else would have known what was happening. He’s adamant there are people who knew, or should have known.

Since sharing his story, he’s been inundated with calls and messages from people in hockey who claim they tried to report James, or have a story of someone else who wanted to but didn’t feel they had enough proof.

”There is no doubt people knew.”

“There is no doubt people knew,” Kennedy says. “I’ve heard from people who were general managers, scouts, telling me they tried to do something about it. Players used to make fun of me on the ice for how close my relationship was with Graham, calling me all kinds of horrible and homophobic names. How could no one pick up on that?”

There are more of James’ victims out there, something Kennedy says he knows because he’s spoken to some of them. He understands the challenges in coming forward. So he doesn’t ever push, even if he also knows how real the pain can be trying to hold it all in.

“Some of these guys are really struggling. They’re struggling with suicide, they’re struggling with addiction and they’re struggling with relationships,” Kennedy says. “We’re worried we may lose someone.”

●●●

A granite cloverleaf-shaped memorial juts out on a windswept stretch of the Trans-Canada Highway just east of Swift Current.

It’s a poignant reminder of the dangers WHL teams face criss-crossing the Canadian Prairies. It is also a permanent reminder of how James’ era in Swift Current was cloaked in tragedy.

On Dec. 30, 1986, the Broncos left town for that night’s game against the Regina Pats. One minute, players were joking and playing cards at the back of the bus and the next, the vehicle catapulted off a highway overpass after hitting a patch of black ice.

Four players — Trent Kresse, Scott Kruger, Chris Mantyka and Brent Ruff — were killed; each is pictured in the cloverleaf monument. The names of the survivors are etched into the momument’s base. Tracy Egeland, listed just below Sheldon Kennedy, was a 16-year-old WHL rookie on the bus. Ruff was his best friend.

On the night of the crash, after calling his parents to let them know he had survived and was cleared to leave the hospital, Egeland returned to his billet’s house overwhelmed and disoriented from the hell he had just witnessed.

Several members of the team’s board of directors and other community members closely associated with the Broncos were at the house. Not wanting to mingle among the crowd, Egeland escaped to the basement, where he was living.

“I go downstairs and guess who’s sitting on the f–king couch looking at me? Graham. I’m 16 years old, I just lost my best friend. Now he’s sitting on the couch, I’m on the loveseat and he’s sitting there just looking at me,” Egeland says in a phone interview from his New Mexico home.

“You got all these guys upstairs not even wondering that that’s not weird. From that day forward, I knew when that happened it was not good.”

”From that day forward, I knew when that happened it was not good.”

The crash occurred in both James’ and the Broncos’ first season in Swift Current; the team had been purchased from Lethbridge during the off-season.

Those circumstances — combined with a team laden with future NHL stars — created a perfect environment where few would question what was happening behind the scenes, Egeland suggests.

And it was a toxic culture created by James, says Egeland, a star in Lethbridge minor hockey who, before the sale, dreamed of playing his junior career in front of family and friends in his hometown.

“If I was my dad to me then, there’s not a chance I would let me go play there. It was a f–king embarrassment… I don’t know how to put it any other way.”

Players could party, miss curfew and skip school without repercussions. James was awkward and creepy, someone who didn’t seem comfortable in his own skin, Egeland says.

While viewed by many as a progressive coach who prioritized skill over toughness, James lacked structure and struggled to motivate once the game began.

James was set up to succeed, Egeland says, simply because of the talent he inherited.

“You got Joe Sakic, Sheldon Kennedy, Peter Soberlak up front. You got Trevor Kruger in net and Darren Kruger in the back end, along with Bob Wilkie and Ian Herbers. As a coach, if you’ve got a team like that, your only problem is who you’re giving minutes to. That’s a coach’s dream,” he says.

“Now, say it would have been a bunch of has-beens. There’s no Joe Sakic, no anybody, and (James) sucks for two years and they decide to get rid of him and he’s out of the game. Then what? So talk about the perfect storm.”

Many players were damaged by their time in Swift Current, and none more so than Kennedy, whose hockey potential was as pure as Egeland had ever seen.

“Sheldon could bring everyone to their feet every period if he wanted to; he was that good,” Egeland says.

“I have never — playing, coaching, even now, watching games — have I ever seen anyone skate like that. Not even close, and I’m not the only guy who would say that.”

He adds: “Everybody can say what they want to say but nobody knows what Sheldon went through. They don’t. Sheldon had to take this on himself.”

It is clear Egeland has been scarred by his time as a Bronco. The part he most regrets is how James’ behaviour in Swift Current made him a confused teenager, complicating his relationship with his high school sweetheart at the time. He’s back with her now, with the two stronger than ever, and he’s thankful for the role she’s played in his ongoing healing.

While he has sought professional help over the years to fully understand the effects James has had on his life, Egeland isn’t ready to discuss the details publicly.

“There’s a lot of guys out there that know exactly what I’m saying and maybe I was affected more than others, but shit happened…” Egeland says. “Graham f–ked a lot of us over, did a lot of things that weren’t right.”

●●●

In 1989, Todd Holt was a small, slender 16-year-old kid with an impish grin.

On the ice, the Estevan, Sask., product had speed to burn. His skill had caught the eyes of scouts while he was tearing up minor hockey in his hometown.

Off the ice, he was the perfect victim.

Like Kennedy, he came from a home where it was a struggle to put food on the table and where his father was coping with the demons of alcoholism.

James had just led the Broncos on their championship run and he called to see if Holt — a Swift Current prospect — might be interested in taking part in a parade to honour the Memorial Cup-winning team. To save money, he told the Holt family that Todd could bunk with him.

“I thought it was a great opportunity,” Holt says. “I was going to (Swift Current) camp that fall.”

After hanging out the night before the parade with a few of the Broncos he knew, he returned to James’ one-bedroom apartment and plunked himself on the couch — a difficult task since the apartment was pitch black. Holt figures he was there no more than a half-hour when he could feel someone grabbing at his feet.

“In my head I’m going, ‘No f–king way. It can’t be what I think it is,’” he says. “His hand then starts coming up my leg so I roll over and nudge him away. It went on forever and I’m f–king scared shitless. Like, this guy has my future in his hands and he’s trying to f–king touch me.”

”This guy has my future in his hands and he’s trying to f–king touch me.”

Finally, Holt escaped to the bathroom. James retreated into the darkness, towards his bed. The next morning, Holt woke with a pit in his stomach.

“In an ideal world you just pick up your bag and jump in your car and leave. You go home and say, “Mom, this f–king guy was touching me,’ and that’s what you do,” Holt says.

“Then you come home and everyone is talking about how excited they are you’re going to play in Swift Current. You start asking yourself if what happened really happened. You know f–king well it happened, but you’re trying to make sense of it at 16 and you can’t.

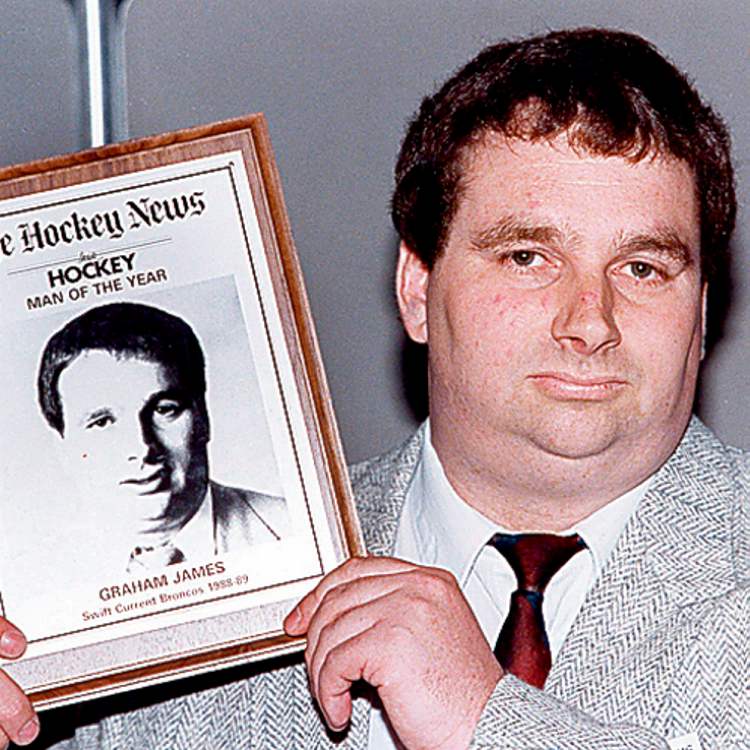

“All I could think of was, ‘Really? This guy won the 1988-89 Hockey (News) Man of the Year. You’re going to accuse this guy?’”

Holt still holds the Broncos franchise record for most goals (216) and points (423). Of his five seasons in Swift Current, he was voted the fans’ most popular player four times and was inducted into the Broncos Hall of Fame in 2007.

With the kind of tenacity Holt displayed on the ice, you would never know he was being sexually assaulted by James multiple times each week. But inside he was falling apart, and had been convinced that James was the only person who cared for him and wanted to see him succeed.

“He manipulated us into thinking this was the way of life, that he needed us and we needed him,” Holt says. “It’s like all those psycho-thriller movies — he made you dependent strictly on him.”

James told Holt he loved him and assured him he wasn’t gay. There were times James even threatened to kill himself if Holt didn’t play along and would beg and cry until he did.

Holt says the manipulation was so calculated and severe that he believed he cared for James.

“He made it look like we were his whole world and he knew we were kind-hearted children. Through all the tough things we had gone through in our lives we still loved our family and wouldn’t let anything happen to the people we love,” Holt says. “He was someone we were supposed to be able to trust and he took advantage of us.”

“He was someone we were supposed to be able to trust and he took advantage of us.”

Sullivan says it’s quite common for sexual abuse victims to form what seems like a genuine care for their abuser.

“Sometimes people describe it as a Stockholm Syndrome-type scenario, where you develop a fairly intense relationship — and it doesn’t take long, just three or four days of that level of intensity — interspersed with mixed experiences. Because you get these acts of kindness and compassion and care that, physiologically, can be very powerful in developing an attachment to someone who is abusive,” he says.

This kind of lasting connection is most common within the family structure, most notably with fathers, Sullivan says. James provided that father figure for many of the players he abused, which not only filled an important void in the player’s life but also created a significant bond and level of trust.

“Children are extremely resilient. While their stories are littered with a horrific litany of abusive experiences, most of them say they still love them, that he’s the only dad that they’ve got,” he says.

“My guess is Graham James really tried to take over that sort of parental role and, for some of the more vulnerable boys he was targeting, became like a father, or uncle or big brother. It’s a very difficult thing for victims of abusers like that to acknowledge they still do have a measure of concern for that individual and it’s not all that unusual.”

Kennedy and Holt both drank to numb the pain of the abuse. James took advantage of that, painting them as raging alcoholics who were out of control and who required his guidance at all times.

“I’d come back from parties and Graham would be sitting at the kitchen table with my billets and he would take me with him,” Holt says.

“He would say ‘No, no, Todd is not staying here tonight. You guys can’t f–king look after him.’ They just watched us walk out, like they did something wrong.”

James eventually convinced the Broncos organization that no one was interested in putting up with Holt’s antics, forcing Holt to move in with him for his last two years.

Holt says other players would come through the house often. The coach would help them with their homework or they would watch a movie.

“Guys would show up and I’d get the f–k out of there,” he says.

●●●

In 2015, James was back on a court docket. He was again pleading guilty to sexually assaulting a former Broncos player during the early 1990s.

Nearly 30 years after being abused by James, that player has now decided to go public with his name.

Lloyd Pelletier grew up in Winnipeg before cracking the WHL’s Medicine Hat Tigers’ lineup for the 1988-89 campaign. He was traded to Swift Current midway through his second season.

Pelletier didn’t want to be publicly named initially during the criminal proceedings because he thought it might affect his work in child welfare and because he was a foster parent. It was also an extremely emotional time for him.

Breaking his silence about something that he had kept buried deep inside was challenging enough, he didn’t need the added attention of having his name in the public realm. But Pelletier says he’s at a place where he can talk freely, even if sometimes his emotions get the best of him.

“I don’t want to say I’m not bothered by it but I have a pretty good handle on my emotions over it and I’ve been coping well enough over the years where I kind of stay in my own little bubble and I try not to…” he says, pausing.

“If I don’t have to go out in public then I don’t. Let’s put it that way.”

“It seemed like everybody… that (James) chose sort of came from a broken family.”

Pelletier has had plenty of time to reflect on what happened to him — and why. He still doesn’t have all the answers but, like most of the others who faced abuse, he lacked a father figure in his life. His parents split up when he was young, and so it was just him and his mother growing up.

“It seemed like everybody, at least everyone I’m aware of that (James) chose sort of came from a broken family,” he says.

“Theo grew up in an alcoholic family; Sheldon, I believe, was also around the same kind of alcohol abuse. Todd’s family was sort of similar and my parents were divorced.”

Pelletier was 18 years old when James first approached him. It started with touching over the clothes and progressed from there, culminating into a similar routine as the others; he was going over to James’ house twice a week.

James started by opening up about his sexuality. He made Pelletier feel like what he was doing was normal, and would mention other players’ names as if they were a part of it.

Pelletier doesn’t expect people to understand. He was raised to respect his elders, and trust the word of authority. He didn’t feel like he was in a position to say no, even if he was confused by what was happening.

“He basically told you that you were his friend and that’s the way he looked at everything, like he wasn’t doing anything wrong. It was like we were there to help him, that it was part of our job,” Pelletier says.

“When somebody with authority has power over you, then how do you not agree with them? Whether you think it’s right or wrong, if they’re telling you to do it then you do it and that’s how I was raised.”

“He basically told you that you were his friend and that’s the way he looked at everything, like he wasn’t doing anything wrong.”

That internal pressure to submit to authority was coupled with the fear of losing everything he had worked for in hockey.

“Basically, you’re screwed. You’re not going anywhere because his word carried a lot (weight with) scouts and your path to the NHL,” he says.

Pelletier is convinced other players knew about what was happening to him. In his mind, given the way his teammates spoke to James, it seemed like everyone was involved in the abuse.

He says teammates often joked about going over to James’ house and masturbating with him. Others would openly tell James to f–k off if he had an issue with them breaking curfew.

“It just made you wonder if this was sort of a brotherhood and everyone was a part of it. That was life in Swift Current.”

“A lot of the stuff you say, you joke around about one another or whatever. But typically you don’t joke about going to the coach’s house and jerking off with him or watching porn,” Pelletier says.

“It just made you wonder if this was sort of a brotherhood and everyone was a part of it. That was life in Swift Current. So how could you say nobody knew?”

●●●

Even before Holt revealed his terrifying account, McLean already knew something was seriously wrong in Swift Current.

Prior to cracking the lineup in his first season, he had injured his shoulder and was ruled out of action for two weeks. To stay in shape, he worked out with James individually.

After one of the first workouts, McLean headed for the showers. A short time later James joined him.

McLean says he was startled at first. James had his own shower, so he saw no point in him being where the players washed up. While McLean was rinsing shampoo from his hair, James reached over and flicked his penis.

McLean, who was six-foot-one and weighed more than 200 pounds, confronted his coach, grabbing his hand and throwing it away. James acted surprised by the reaction and claimed he was just joking around.

Then he did it again.

“I pushed him up against the wall and told him to f–k off and keep his hands to himself. From that day forward he never approached me ever again. He never even really talked to me again after that,” he says.

“Looking back now, he was testing me to see what he could get away with. Was I another small-town kid with big dreams who was willing to put up with the coach grabbing my balls? I wasn’t that kid and he quickly realized.”

”Looking back now, he was testing me to see what he could get away with.”

But he didn’t learn of Holt’s anguish until his second season. And it took weeks before McLean convinced team captain Rick Girard and a few other veterans that Holt was being tormented. But once onside, they approached assistant general manager Doug Mosher.

Mosher, taken aback by the serious allegations and the threat of a mass team revolt, arranged for the players to meet with team president John Rittinger the next morning.

McLean says the players were nervous, but told Mosher and Rittinger what James was up to and that they refused to play for him. Mosher and Rittinger left the room a few times to chat privately and, after confirming with the players that they were sure firing James is what they wanted, assured them he would be let go.

A short time later, everyone was at the arena for practice.

“We’re sitting in the room anticipating we’re going to fire our coach and in walks John Rittinger and he said, ‘Guys, we’ve heard you and we’ve talked about it. We’ve informed Graham of your wishes and Graham has asked that he has one last chance to address the team,’” McLean recalls.

“I remember I stood up and said, ‘Are you f–king kidding me? No!’ And John Rittinger looked at me and said, ‘Darren, you haven’t been here long enough to decide what’s good for this team or not. We have decided that Graham has been here, he’s seen this team through thick and thin, he deserves an opportunity to address the team.’”

James began to single out each player and questioned how, after everything he had done for them, they could turn their backs on him.

One by one players started to agree to give James another chance. That is, until it was McLean’s turn.

“It came around the room to me and Graham wouldn’t even look at me. I stood up and said, ‘Hey, you guys might respect him for what he’s accomplished in hockey but how can you respect him as a man? What he’s doing is wrong — don’t you see that?’

“And the guys seemed exhausted and said they just wanted to play hockey. No one wanted to deal with this stuff at 17 and 18 years old.”

”No one wanted to deal with this stuff at 17 and 18 years old.”

The only player still in McLean’s corner was Kevin Powell, a 20-year-old winger in his first season with the Broncos. Powell died in a motorcycle accident in 2002.

But it was too late. Rittinger had framed the showdown as a team vote in favour of James staying.

“So Rittinger walks back in and said, ‘All right, guys, this is going to be a hard enough year without any of this bullshit. You have collectively decided to give him another chance so I don’t want to hear about it ever again.

“Nobody talks about this meeting. Nobody talks about anything. We need to focus on rebuilding this team and moving on and moving forward.”

No more than five minutes later, McLean’s name was blaring over the intercom with a request he head to the front office. Rittinger and Mosher called the 20-year-old McLean a cancer, accused him of trying to ruin the team, and that he was the one who was done. They cut him a cheque for about $2,000 and told him to leave town.

“I said, ‘Deal. I hate all of you,’” McLean says. “I went and grabbed my skates, went back to the front office to pick up my cheque and left.”

●●●

Rick Girard was just fresh off winning gold at the 1994 World Juniors, but now he had the weight of the world on his shoulders.

He was 19 years old and at the apex of his young hockey career, but instead of chasing his NHL dream, the second-round pick of the Vancouver Canucks was trying to navigate the messy politics of hockey boardrooms.

Girard was home in Edmonton for a break following the Czech Republic-hosted junior championship, when word reached him that his junior hockey club was in disarray.

“The biggest thing people need to remember is that when you’re 17 and 18 you’re going through a period of time in your life where you’re trying to live out your dream, so you’re pretty self-involved,” he says. “But that last year I grew up pretty fast. I never imagined that’s what I would be involved in when playing junior hockey, that’s for sure.”

”I never imagined that’s what I would be involved in when playing junior hockey, that’s for sure.”

During one of his first games back in Swift Current, there was a physical altercation between James and a player who was being abused.

James was punched in the face, which left his suit bloodied and forced him to return to the bench in the third period wearing track pants. That altercation is what spurred the meeting between a group of players and Mosher and Rittinger.

“We wanted James gone and that was our whole goal,” says Girard, speaking publicly for the first time about what was happening inside the Broncos’ locker room. “Guys had come forward, we knew it was absolutely wrong what he was doing and we assumed there were even more players. We knew this guy shouldn’t be around hockey.”

”We knew this guy shouldn’t be around hockey.”

After James was allowed to stay, Girard says he continued to talk with both the Broncos’ executive and the top brass of the Western Hockey League.

Girard says he had multiple conversations with Rittinger and estimates he spoke to then-WHL commissioner Ed Chynoweth on eight different occasions. He says the conversations consisted of what he had heard from other players, who he believed was involved and what might be the best decision moving forward, including possible replacements for James.

Rittinger could not be reached for comment, while both Chynoweth and Mosher died in 2008. The WHL renamed its championship trophy the Ed Chynoweth Cup to honour his long service to junior hockey in Canada months prior to his death.

Girard says he struggled to make sense of it and felt it was a lot of pressure to deal with as a 19 year old. Neither Rittinger nor Chynoweth seemed interested in doing their own investigation, so they relied on Girard. And because Girard hadn’t spoken to the victims, he could only relay what he had heard from McLean, who was no longer around.

“You’re young and you’re trying to make your own path and now you have to go up against a Hockey Man of the Year-type guy?” Girard says.

“How much evidence did I have? Until someone was ready to step forward themselves, I wasn’t going to be the one spewing shit on their behalf or assuming and saying stuff if they weren’t ready to step forward.

“Had someone told me what happened to him I would have stepped forward right away. We did as much as we could.”

Still, Girard wasn’t just going to ignore what had happened. After multiple conversations, both Rittinger and Chynoweth said that James would be gone at the end of the season.

So when it was announced after the 1993-94 season that both Rittinger and James would be moving on from the Broncos to start up the Calgary Hitmen, the WHL’s newest team, and that it was Chynoweth who cleared the way, Girard was left to search for answers.

”All I can say is if you choose to go along with that, well, that says everything you need to know about a man’s character.”

“All I can say is if you choose to go along with that, well, that says everything you need to know about a man’s character,” Girard says.

“I thought it was solved. I thought the kids coming behind me, they’re not going to have to deal with this anymore and hopefully, at some point, someone would come forward and they would start the process of putting him in prison. Because they had the facts and they had the story and they had the hurt and everything else to do it.

“So when we left there the feeling was he wasn’t going to be able to hurt anyone anymore.”

●●●

Near the end of his tenure with the Swift Current Broncos, Lorne Frey’s gut instincts told him that a player had likely been a victim of sexual abuse in the past.

But the assistant general manager, who arrived in Swift Current as the same 1986-87 season as James, had no idea the abuse was occurring from within the organization.

He would talk about the player’s erratic behaviour with his wife, Jan, who worked at the local safe shelter. She, in turn, told him everything seemed to point to some sort of abuse, likely sexual.

Concerned, she gave him some pamphlets about child abuse, which he passed on to James. Frey says James took a brief glance before tossing them on his desk and saying, “what I don’t know won’t hurt me.”

Frey then tried to intervene on the player’s behalf by bringing in a local counsellor to speak with the coaching staff. That counsellor said it was textbook case of someone suffering from sexual abuse and that it was imperative the two speak.

“Then Graham says, ‘Well, no, he won’t talk to you.’”

Less than a month later, Frey was demoted to a scouting role and eventually let go after he refused to accept a position that would keep him on the road and away from the rink. At the time it didn’t make any sense. The team was winning and setting up for an even stronger season the following year.

Frey believes it was because he was getting too close.

“If I had known he was a predator, I would have been able to put two and two together, I would have known why all this was taking place,” he says.

“If I had known he was a predator, I would have been able to put two and two together.”

Frey was hired a short time later by the Tacoma Rockets, now the Kelowna Rockets, and has been there ever since. He’s credited for scouting the likes of NHL stars such as Shea Weber, Duncan Keith, Jamie Benn, Tyson Barrie and Tyler Myers. After 30 years with the organization, Frey recently stepped down as the team’s assistant general manager and director of player personnel.

It was while with the Rockets, years after he was fired by the Broncos and not long before James was caught, that Frey was driving in the car with Jan. She looked at him and made a bold prediction about James.

“We were driving to Calgary that day, we’re driving down the street and she said, ‘You know what, Lorne? He’s a pedophile. It may take one year, two years, three years… but eventually someone is going to spill the beans on this guy,’” Frey says.

“I’m sitting there going, ‘You’re crazy!’ And she just said, ‘No, Lorne. He is.’”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

Jeff Hamilton is a sports and investigative reporter. Jeff joined the Free Press newsroom in April 2015, and has been covering the local sports scene since graduating from Carleton University’s journalism program in 2012. Read more about Jeff.

Every piece of reporting Jeff produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.