Bay part of city’s DNA forever

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/12/2020 (1922 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On Nov. 18, 1926, more than 50,000 people — almost one-third of Winnipeg’s population — came out to celebrate the grand opening of the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s vast new Portage Avenue department store.

At five o’clock last Monday evening, without ceremony, the lights were turned off and the doors locked for the last time, as the grand old store quietly slipped into memory.

The Hudson’s Bay Co. opened Winnipeg’s first retail store within the stone walls of Upper Fort Garry 208 years ago and had maintained a commercial presence downtown until last week. By closing what was once the Bay’s flagship Canadian store, a unique relationship between a company and a city is lost, but HBC’s presence in downtown Winnipeg will forever be embedded in the city’s very DNA.

Evidence of the Bay’s influence in downtown can be found everywhere, even in the street names. Fort and Garry recognize the fort, Edmonton and Carlton were named after other western trading posts, and McDermot, Bannatyne, Hargrave, Donald and Smith all honour HBC employees. The Hudson’s Bay Co. affected almost every aspect of early Winnipeg, and if you know where to look, you can find its influence in the streets, buildings, and places across downtown.

The location of the city itself was decided when in 1822, HBC established its fort near the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, on land that had been an ancient crossroads for Indigenous people.

The fort continued the area’s role as a centre of trade, becoming a critical link in a colonial transportation network, moving people and goods across the West. HBC would build Winnipeg’s first two bridges, later purchased by the city, establishing the location of today’s Norwood and Provencher bridges.

The $600,000 tax bill paid by HBC when the city was incorporated was used to lay the first paved roads.

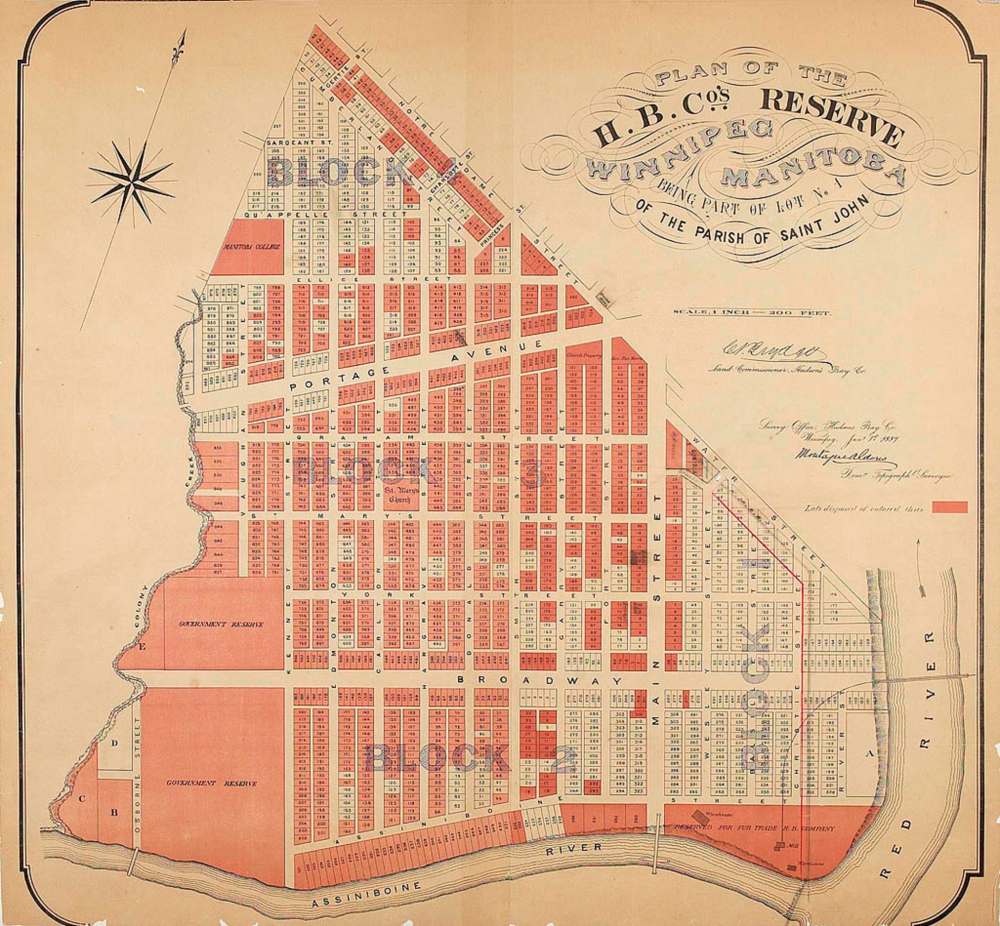

With the fur trade fading, in 1869 HBC transferred control of Rupert’s Land over to the British Crown. As compensation, the company retained land adjacent to its active posts across Western Canada. This included nearly five hundred acres in downtown Winnipeg, known as the Hudson’s Bay Reserve.

A survey of the land was sent to London, England, where the city’s first urban plan was laid out. To maximize profit, the plan established wide streets with large blocks in a regular grid pattern, parallel to the Assiniboine River.

These large streets still define the character of the area south of Portage Avenue today and make the outline of the HBC Reserve easily recognizable in a Google Earth image of the downtown.

As a big company headquartered halfway across the world, HBC moved slowly. The aggressive entrepreneurs of the young city didn’t like the company’s rules or inflated real estate prices and rebelled by buying land along the edges of the reserve, resulting in both the Exchange District and Portage and Main being located at the closest point to the fort along Main Street without being inside HBC-controlled land.

To combat the new development outside of their property, HBC created Broadway, as Western Canada’s first boulevard. This was intended to become the city’s main thoroughfare and draw economic activity to the reserve land. To bolster this effort, the well-travelled Portage Trail was left out of the reserve plan, despite a previous agreement that it would be maintained.

The city took the company to court, finally winning, resulting in Portage Avenue being cut through the surrounding regular street grid at an odd angle, still seen today.

Having missed out on Winnipeg’s first commercial boom, HBC decided to transform their land into an upscale residential neighbourhood. Plots were set aside for schools, churches and government to help attract people and jobs to the area.

The strategy worked, and most of downtown became tree-lined residential streets, much like West Broadway and Armstrong’s Point.

Street widenings to accommodate ever-increasing traffic volumes would eventually eliminate most of the area’s more intimate feel and the wood-frame houses and apartment buildings would decades later be easy targets for demolition, resulting in today’s proliferation of surface parking lots in the area south of Portage Avenue.

This is contrasted by the Exchange District, where more substantial buildings were built. The consequence is that an inadvertent legacy of HBC from a century ago can be found in Winnipeg’s many parking lots.

When Upper Fort Garry was finally demolished, the first Hudson’s Bay Co. department store was built down the street, in 1881. It was a handsome three-storey warehouse-type building at the corner of Main Street and York Avenue. If it were still there today, VJ’s Drive-In would be sitting beside it.

A small campus grew around the store, and although the building is gone, others remain as evidence of the Bay’s first Winnipeg department store.

On the lane behind sits a small, non-descript warehouse with an oddly ornate cornice that seems out of place for a utilitarian building. This was once the campus powerhouse.

Behind that, is a handsome little red brick building on Garry Street that was built in 1911 as the company’s vehicle garage. It has been easily recognizable as the Keg Restaurant for almost 50 years, with the HBC crest still visible centred on its façade. Hiding under the modern-looking skin of the Northwest Company’s offices on Main Street, is a 110-year-old building that was once the HBC department store warehouse.

When Eaton’s built its massive new store on Portage Avenue in 1905, it signalled the beginning of the end for the Main Street Bay. Sales in the store dropped by 11 per cent in the first year and it became obvious that Portage Avenue would be the commercial heart of the young city.

HBC officials began looking for a new site and settled on a seven-acre property at the western edge of downtown, home to a few houses, laid out on Winnipeg’s first cul-de-sac and the original Blackwoods soft drink and bottling factory.

Although the property was purchased in 1911, the war and economic recession would delay construction of a new store for many years.

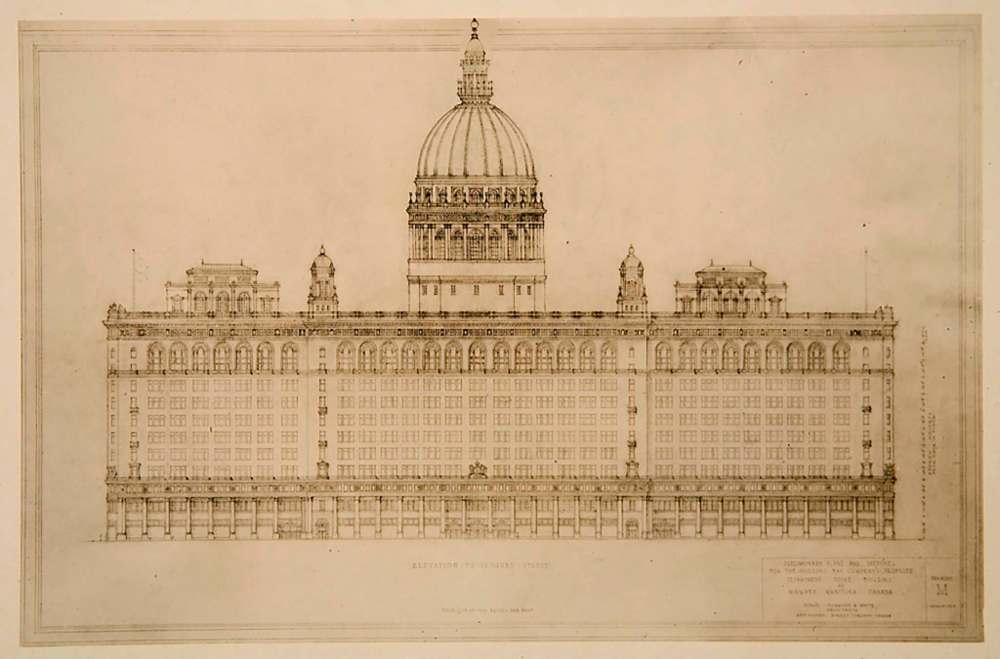

In 1916, Eaton’s announced that it would build a twin to its massive department store, as a catalogue sales facility. The new building (today City Place) would bring the total square footage of the Eaton’s campus to more than 1.6 million square feet. In response to this, plans were drawn up in 1917, for a dramatic new Hudson’s Bay building.

The ornate 12-storey Renaissance Revival design was capped with a dome modelled after the iconic St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and would rival the Manitoba Legislative Building in prominence. HBC officials decided the design was too unlike stores that had been built in Calgary and Vancouver, so it was shelved.

A few years later, plans for a makeshift two-storey building were developed that could be constructed quickly and later have four storeys added on top, but this scheme was also rejected.

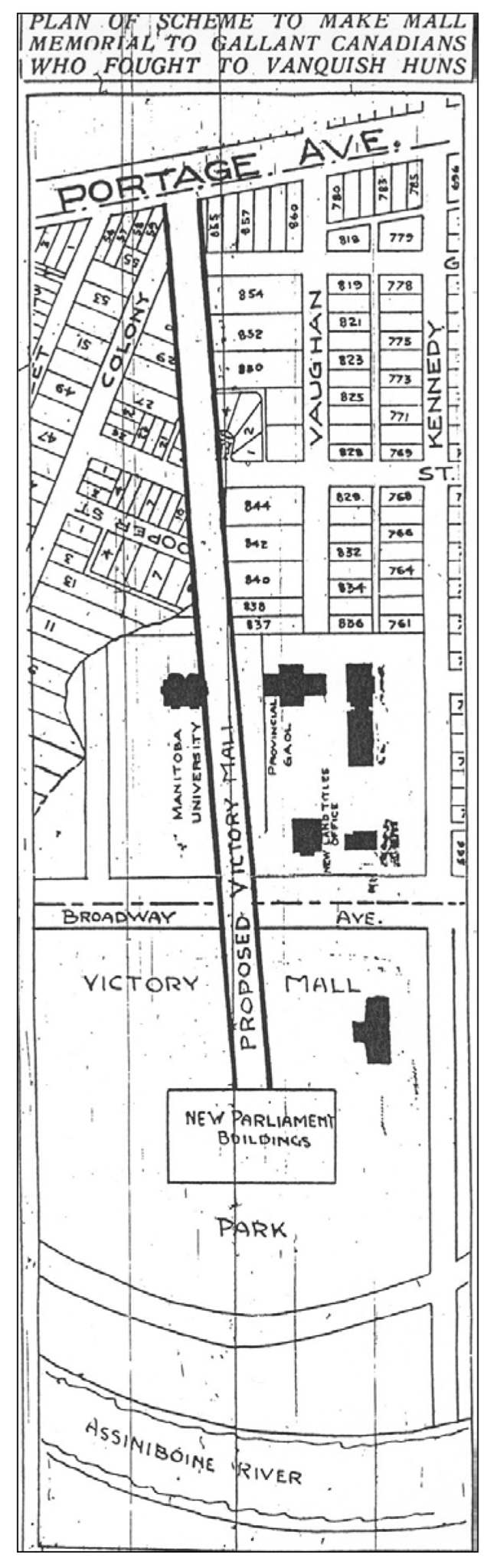

Further delays would arise when the City of Winnipeg decided that a formal commemorative boulevard, patterned after cities like Paris and Washington D.C., would be built, leading from the new Legislative Building to Portage Avenue.

First drawn on direct axis with the Golden Boy, it would slice through the HBC’s property and put any new store on the west side.

HBC fought this plan and convinced the city to approve the “crooked plan,” incorporating a three-degree angle to what was called The Mall, later Memorial Boulevard, so that their site could be located on the downtown side of the promenade.

Finally, in 1924, Montreal architect Ernest Barott, who had recently completed Chateau Lake Louise, was hired to create a final design. He was ordered to follow the corporate style previously established in other cities.

This desire to replicate older buildings gave the Winnipeg design an appearance that it was built earlier than its construction date would indicate.

The plan was to use a white terra cotta façade, like other western stores, but the mayor of Winnipeg, backed by the stone-cutters union lobbied the company to use local Tyndall stone, which they claimed would stand up better in Winnipeg’s climate. It took time, but the company finally agreed.

The use of Tyndall stone contributed $400,000 to the local economy and would inspire a proliferation of Tyndall stone buildings across downtown, including the adjacent Winnipeg Art Gallery, built 50 years later.

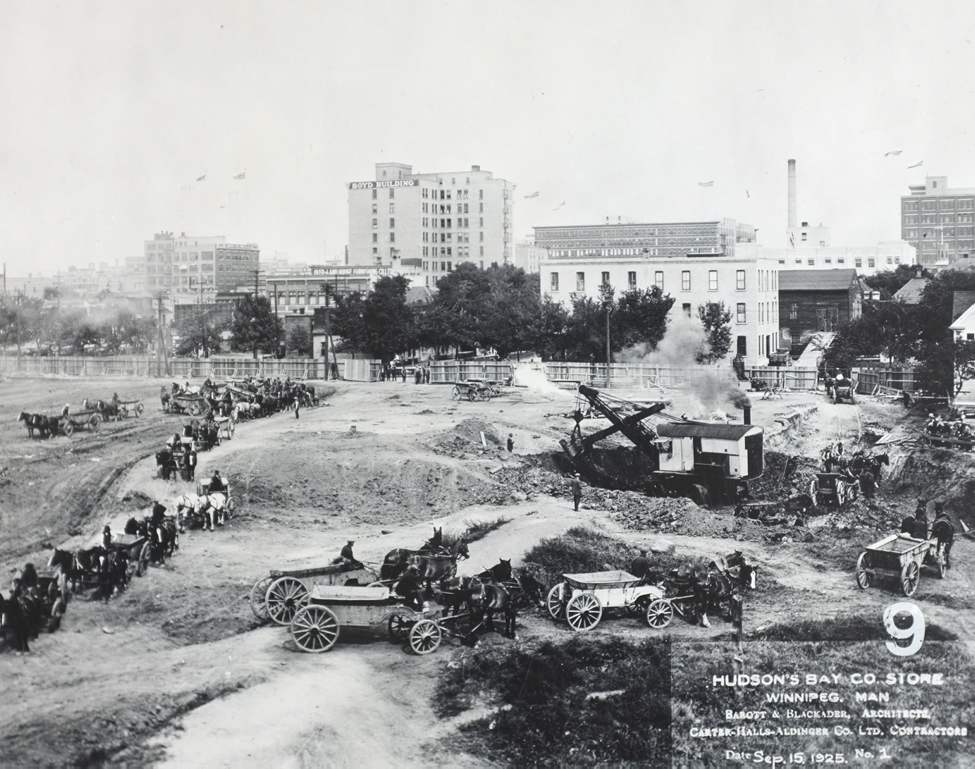

On Sept. 2, 1925, a sod turning was held and a building permit worth more than $5 million, the largest in Winnipeg’s history, was issued. It was a true Manitoba building.

The cement came from the plant that would eventually become the lakes of Fort Whyte, the steel came from Selkirk, and the stone from Garson. An army of more than 1,000 local workers would complete the largest concrete building in Canada in only 14 months.

With 1,800 staff and 63 departments, the building opened in November of 1926 to great celebration, cementing Portage Avenue as one of the premier retail streets in Canada.

For generations, enjoying the window displays at Christmas, or sharing a lunch at the Paddlewheel Restaurant, would be honoured local traditions.

The building would continue to evolve over time. A unique original feature was a covered pedestrian arcade that ran along the sidewalk. The arcade walls and floors were covered in marble and vaulted ceilings ran along its length.

It was later removed and replaced by the current canopy, because it became home to panhandlers during the Depression.

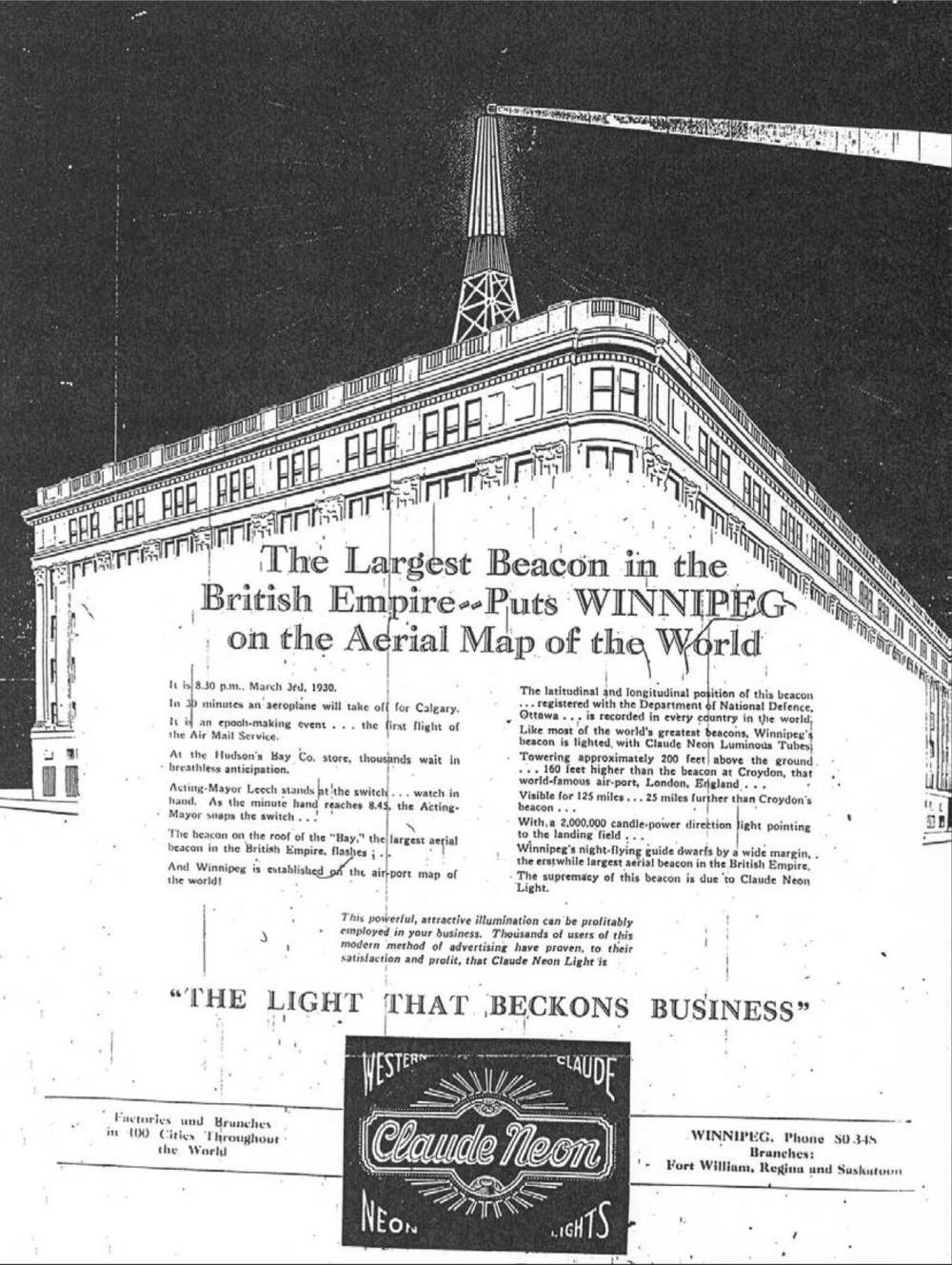

A few years after opening, to coincide with the first air mail delivery from Calgary to Winnipeg, a giant navigation beacon was installed on the roof. The light was so bright, it could be seen 160 km away and was celebrated as the largest beacon in the British Empire. The base for the light is still on the building’s roof and was recently given heritage protection.

In the 1950s, the Bay would build the first parkade on the prairies, but with the proliferation of the automobile, retail habits began shifting from downtown to suburban malls with ample parking.

By the 1990s the store would be in decline. Since then, as if the store itself no longer existed, Winnipeggers have debated what to do with the Bay building almost as much as the opening of Portage and Main.

Many proposals have come and gone. It was considered as a location for Manitoba Hydro’s new offices in 2002, and again for Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries in 2015. The University of Winnipeg looked at moving into some of the space and several private developers have tried to make projects work.

Most often, these investigations were stopped by the cost of redevelopment and sheer scale of the building.

Most proposals have looked at the idea of opening holes in the middle of the building to reduce the floor area and bring light into the deep floorplates.

If you ask 10 Winnipeggers what should be done with the Bay building, you will get ten different answers — an archives, a school, a hotel, affordable housing, convention space, a waterpark (of course).

Overarching every idea is the need to address the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s colonial history and use any redevelopment as a contributor to reconciliation for Manitoba’s Indigenous community.

The reality is that the large scale of the building, having the same floor area as the 30-storey Richardson Building, dictates that many ideas will be needed to make any redevelopment feasible.

Even through the store’s decline there were some recent successes that we can look to for inspiration.

The Bay operated a grocery store in the basement for 87 years, remaining an important part of the neighbourhood for generations of people who live downtown. The grocery was so popular that it was almost doubled in size in 2002.

In 2010, a Zeller’s discount retailer was located in the building, and for its three-year run would be one of the busiest locations in the city.

Even with its retail presence reduced to two floors, the Bay remained one of the largest department stores in Winnipeg and was an important contributor to downtown living.

New uses might find success by looking to engage the downtown and surrounding neighbourhoods, making it a community focal point that brings employment, services, and opportunity to the residents of the inner city.

Even with the store closed, the Hudson’s Bay Co. will always be part of Winnipeg’s story. After more than two centuries, HBC will no longer have a footprint in the downtown, but if we think as big as they did in 1926, redevelopment can be an opportunity to have a similar impact on our city for the next 94 years.

It will take a strong community effort, dedicated government leadership and high levels of public investment, but if we find the right solutions, the grand old Bay building could regain its place in our civic traditions for the next generations.

Brent Bellamy is creative director for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.