Police back on trail of real estate agent’s unsolved 1979 slaying Investigators travel to Medicine Hat, arrest and release onetime Winnipeg car salesman after polygraph, getting DNA sample

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/09/2020 (1903 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

More than 41 years after the unsolved slaying of a Winnipeg real estate agent, the cold case has become active as Winnipeg police recently travelled to Medicine Hat to arrest a suspect.

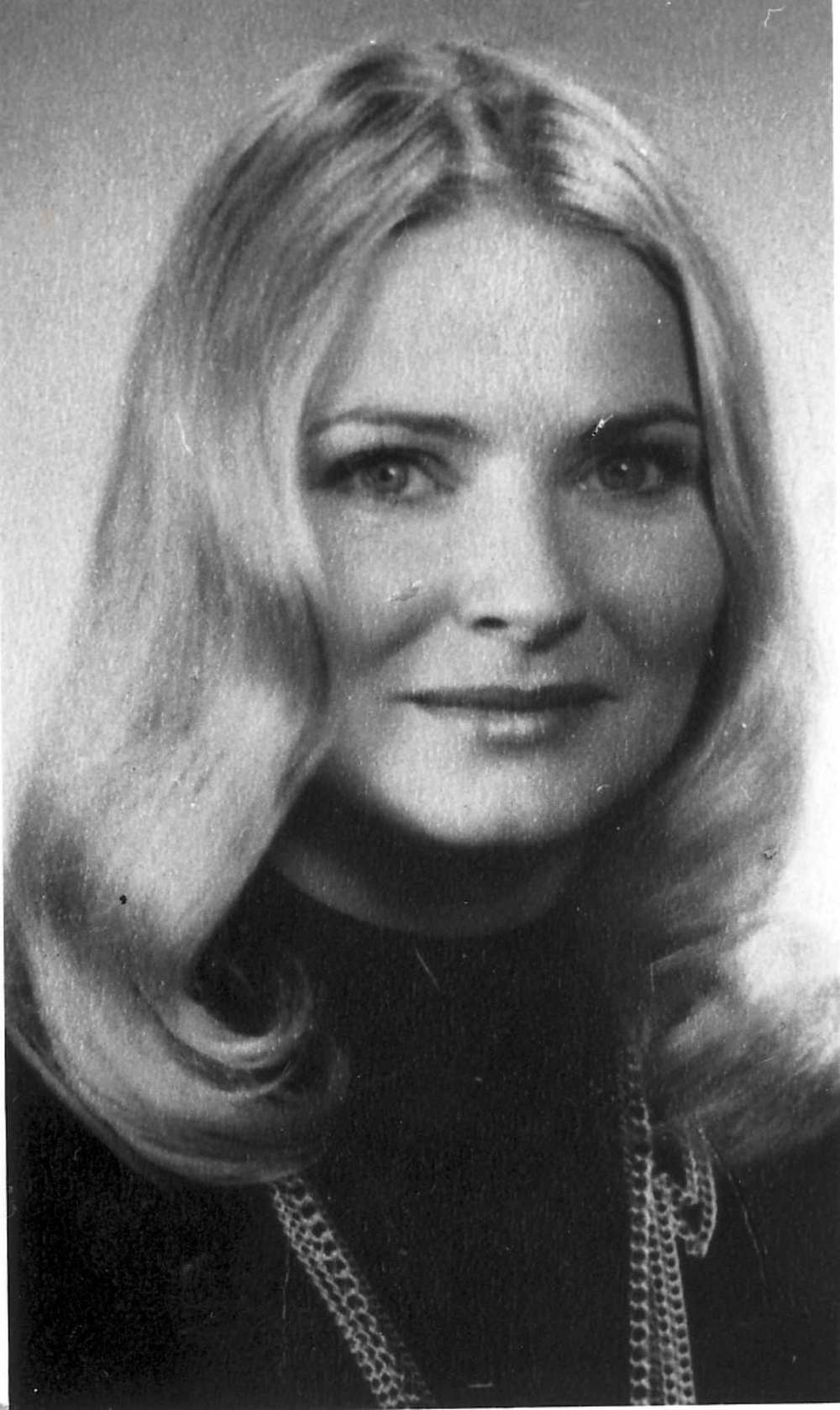

But once there, the 63-year-old Medicine Hat man was released without charges in connection with the 1979 homicide of 31-year-old Irene Pearson.

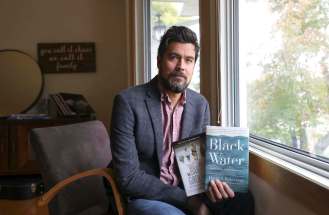

Lester Landry said he was detained and interrogated as a murder suspect for more than 16 hours at the Medicine Hat police station Sept. 3 and into the early morning hours of Sept. 4 before officers drove him home without laying criminal charges.

In an interview with the Free Press, he said he did not kill Pearson, but over the years he has been questioned by police more than once about her murder. He has long said he believes he was the last person to talk to Pearson on the phone before she was killed, and has been haunted by it ever since.

“I don’t have money for a lawyer. I’m the perfect (patsy) for any police department to take advantage of,” Landry said. He said he lives on disability benefits, with a service dog for post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood abuse.

Winnipeg police would not comment on specifics of the case.

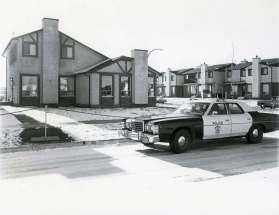

On the evening of Nov. 15, 1979, Pearson was set to show a new property in the Tyndall Park area for Castlewood Homes. The showing never happened. The next morning, she was found dead in the basement of one of Castlewood Homes’ other vacant homes, at 114 Kinver Ave. She was hit on the head and stabbed 31 times. In the years since, police have said they believe her killer was someone she knew, someone with whom she willingly went to the second house.

At the time, Landry was a car salesman in his early 20s with a warrant out for his arrest on fraud charges he said related to passing bad cheques. He says he’d met Pearson about a year earlier, through one of her boyfriends, and was trying to sell her a station wagon. On the night Pearson was killed, Landry says he phoned her at the show home office to ask her if she wanted to see a car that had just come in. He said he offered to drive it over to her.

“Her last words to me were, ‘No, that wouldn’t be a good idea right now,’” Landry said.

Forty-one years later, long after he thought he’d been cleared as a suspect in Pearson’s death, Landry was arrested.

The day before police showed up at his door with an arrest warrant, a copy of which he provided to the Free Press, Landry said he went voluntarily, without a lawyer, to talk to Winnipeg investigators.

“I went there with the intention of trying to help them. I want this solved. It’s not like I was trying to fight them,” he said.

He said he voluntarily gave a DNA sample, but walked out when police asked him to take a polygraph test. He told the Free Press he had misgivings about submitting to the test because of his PTSD and his concerns that it would be administered in a biased way.

“When they tortured me, they were feeding me information on how it was done, the extent of her injuries, and told me how I done it. They pounded that into me, and then they hook me up to a machine to see if I’m lying.” — Lester Landry

After being detained more than 14 hours, he agreed to take the lie-detector test. Shortly after it was over, Landry said he was released, though he said police told him the results weren’t in his favour.

“After the polygraph they told me I failed and they wanted to know why and how I done it,” Landry said, referring to the homicide.

“I believe that there’s no reason for me to fail a polygraph because I did not murder Irene Pearson.”

Before they released him, Landry said police told him they would forward their information to the Crown’s office for review.

Pearson was the adopted daughter of Winnipeg police officer George Gray Smith, who served on the force for 31 years. He died in 1971.

A 1993 Free Press investigation reported further police connections to the case, stating Pearson had dated at least two men who ended up joining the WPS. One of the officers who responded to the scene the day she was found dead had been a high-school boyfriend, and another was a junior homicide detective.

In July 1993, a month after the Free Press published several news stories about the case, the newspaper reported police were re-investigating the homicide, starting with reviewing a tip the newspaper had obtained. No details about the tip were ever reported, but Pearson’s case has continued to generate public interest.

The last time police spoke publicly about it was in 2016, when investigators said they were looking for a suspect they described as a white male between 22 and 30 years old with an average build and medium-length brown hair, who may also have had a moustache.

Police said they believed one of the last people in the home with Pearson was driving either a red or blue newer model Plymouth Volare or Dodge Aspen. Investigators released a Crime Stoppers re-enactment video and said they wanted to talk to construction workers who built the Kinver Avenue home where she was found dead.

Over the years, Landry, who describes himself on social media as “an advocate for people with disabilities and human rights for all people,” said he has spoken to police three or four times about Pearson’s death, including instances where he has approached police to talk about the case and point them to people he thought they should look at.

The first time he was questioned was a few days after the murder. He says he called police to let them know he thought he was one of the last to speak to Pearson. He was arrested on outstanding warrants, and he had a bloody knife he claimed to have butchered a rabbit with while on a hunting trip. The knife was sent away for testing, Landry provided an alibi he said police checked out, and he was never charged. Prior to his arrest this month, the last time he said he talked to police about Pearson was in the early 1990s.

“I appreciate the fact that they’re still looking into it. I’m glad that the case is still active. I really hope that they solve it. And after the DNA, after the polygraph — they claim that I failed it or whatever — I hope we can move on. I hope that they… stop focusing on me. I can’t blame them. I’m not blaming them for looking at me. I’m not blaming them. What I really have a problem with is how I was treated,” he said, describing the interrogation as “torture.”

“When they tortured me, they were feeding me information on how it was done, the extent of her injuries, and told me how I done it. They pounded that into me, and then they hook me up to a machine to see if I’m lying.”

He said the interrogation — which included delving into his history of being physically and sexually abused as a child — triggered his PTSD.

Landry said he considered suicide after the interrogation, and he said he believes police don’t care if he kills himself.

“I really think that they really don’t care. Maybe because if I did kill myself, then they could pin it on me, right? Then it would be case closed. Then it would hit the front page of every major newspaper in North America, and they would be friggin’ heroes, right?” he said.

“What they did to me has led me into a black hole where the light at the end of the tunnel just might be a train.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.