The healing journey While the sting of losing their son to drug addiction will never soften, it continues to inspire Scott and Anne Oake to do everything they can to save other people’s sons and daughters

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/09/2018 (2643 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was the kind of birthday celebration Bruce Oake would have loved.

On Aug. 22, the day Bruce would have turned 33, his family held a star-studded dinner at the Metropolitan Entertainment Centre in downtown Winnipeg to raise money for an addictions treatment centre that will bear his name.

Billed as “Hockey Night in Canada at the Met,” the gala evening attracted Canada’s hockey royalty — Ron MacLean, Don Cherry, Elliotte Friedman and Jonathan Toews, to name a few — and raised awareness and cash for the proposed Bruce Oake Recovery Centre.

As glittering as the hockey personalities were, arguably the brightest star was Bruce’s younger brother, Darcy, an illusionist who rocketed to international fame after a star turn on the TV show Britain’s Got Talent.

On this night, Darcy unveiled an illusion he’d been crafting for some time — a heart-tugging masterpiece in which he used a deck of cards to tell the story of the powerful bond he shared with his brother, who died of a heroin overdose in 2011 at the age of 25.

The final how-did-he-do-that flourish of the illusion involves Darcy spreading the deck on a table to reveal, one card at a time, not queens and jacks and kings, but a treasured photo of the two brothers together in happier times.

It left the audience shaking their heads in astonishment, not sure whether to bang their hands together in appreciation of the magician’s skill or shed tears over the loss of a promising young man’s life to the scourge of drug addiction.

“The goal is always to put something together that comes from an authentic place that’s more than just a trick,” Darcy explains later. “It’s always been something I’ve tried to touch on in the show a little bit, and it’s just the next evolution of telling the story.

“It definitely tugs on the heartstrings and people want to clap but don’t feel comfortable clapping… which is good. It’s cool. It’s a neat emotion to evoke from people.”

The emotional pinnacle of the evening came as Bruce and Darcy’s father, Scott Oake, a longtime fixture on Hockey Night in Canada broadcasts, talked bravely about the agony he and his wife, Anne, endured while watching their once talkative, fun-loving eldest son transform into an emaciated junkie and drug dealer.

It’s a painful story for the Oake family to share, but it’s one they are determined to tell unflinchingly as they attempt to transform their overpowering grief into a vision of hope — a 50-bed, long-term drug treatment centre they are determined to see rise on a 2.5-acre site near Sturgeon Creek, now home to the shuttered Vimy Arena.

Two weeks after the event, in the comfort of their Linden Woods home, fresh from a trip to their cottage, the Oake family sits down with the Free Press to tell their story once again.

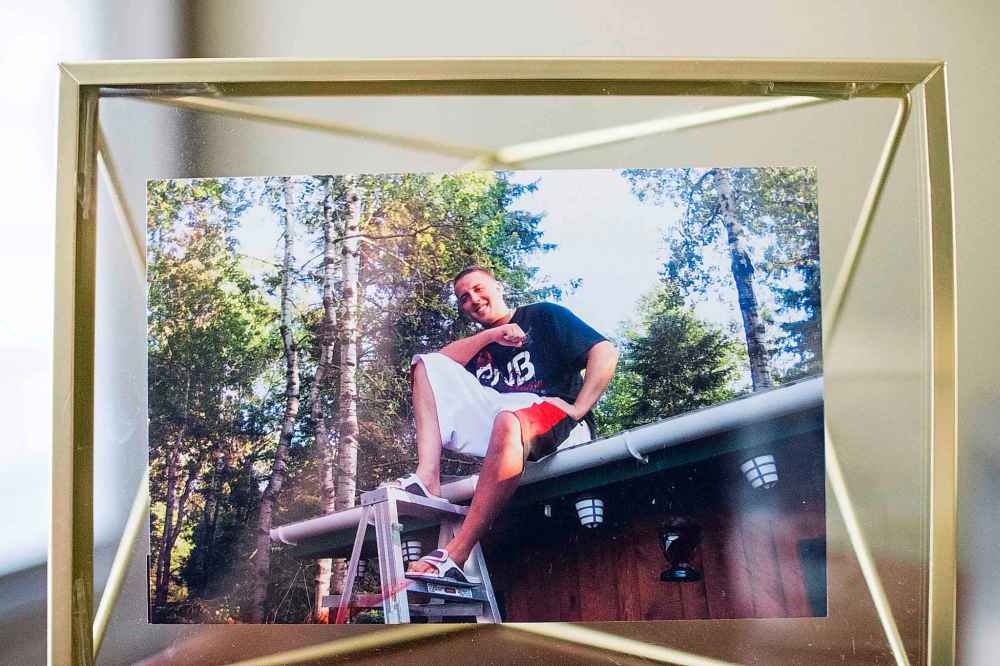

On the wall next to their dining room table hang dozens of framed photos of Bruce, a young man who, before being crushed by the grip of drug addiction, was a talented Canada Games boxer and an up-and-coming rap music performer. An urn containing Bruce’s ashes rests on a table in the family’s living room.

“One of the reasons we tell our story is that we were always with Bruce, every step of the way, we never lost contact with him, but if anyone can learn something from some of the mistakes we’ve made, more power to them,” Scott says as the family gathers in the dining room and their dog, Lewis, meanders at their feet.

“It (addiction) is not about socioeconomic standing… Bruce and Darcy were raised in the same loving home, raised the same way, and one guy is taking the world by storm and his brother’s life ended in tragedy. Anne always says if it can happen to us, it can happen to anybody.”

The sadness is always there, but there’s also a subtle sense of joy in the Oake household, the sort of understated happiness that comes from using the power of grief to fuel a dream.

The Oakes’ dream is not just to build a recovery centre in their son’s memory; it’s to build a centre that will save the lives of others like Bruce, young men caught in the vise-like grip of drug addiction.

“We want to make Bruce’s life mean something. For us, it was either wallow in our misery for the rest of our lives, me never getting out of bed again, or trying to do something to make a difference,” his mother, Anne, explains quietly.

Nodding his head, Scott adds: “When you lose a child, you have choices, and one is to resign yourself to your grief and carry on as best you can. Another is to give voice to your grief and try to make your child’s life mean something, as tragic as his passing might have been, which is what we’re doing.”

There’s no question the treatment centre plan is at a critical stage. One volatile public meeting has been held, and another two are expected as part of the rezoning process required before the land can be turned over to the Oake family foundation.

“We had two sessions in one day (on Aug. 14); it was the first of our public consultations that are a requirement of the rezoning process … we have to hold a couple more public consultations and present to committees at city hall and hopefully, there will be a final vote before the year is out. But it’s a long and involved process and we’re following it to the letter,” Scott says.

“The city gave us the property contingent on rezoning. If we can’t get it rezoned to what we need it to be, it doesn’t work. And we’re not taking anything for granted in the rezoning process.

“We have reached the point of no return in this project. The Bruce Oake Recovery Centre will be built somewhere, but we think the Vimy property is an ideal location for it because it’s serene, it’s not immediately adjacent to any residential property, and its on a public transportation route so it meets the needs of the centre perfectly.”

The Oakes’ dream of saving lives has proved to be a divisive issue in the community, with opponents venting their anger at the first public meeting at the Sturgeon Heights Community Centre.

Some critics are angry city council agreed, contingent on rezoning approval, to green-light the $1 sale of the Vimy site to the province, which would turn it over to the Oake family foundation on a 99-year-lease.

“I am not against rehab at all,” one 75-year-old resident said at the first public meeting. “I am very much against it in a residential area.”

The second public meeting is set for Sept. 25 at Sturgeon Heights, with sessions at 3:30 and 6:30.

While they have heard their share of cruel and cutting remarks, the Oakes said they refuse to engage in a war of words. They are committed to ensuring everyone on both sides of the debate has the chance to be heard.

“I think we have a responsibility to educate people the best we can, answer all their concerns,” Scott insists. “That is the purpose of an information session we had last December and the three public consultation sessions we have to have as part of the rezoning process. It could be more because we want to get the message out there and let people know they have nothing to fear.”

Asked what that message is, Scott pauses briefly. “The message — a treatment or recovery centre in the heart of a residential urban neighbourhood can function perfectly, and does all across the country and in several locations in Winnipeg,” he finally says.

“Residents of the area have nothing to fear. The message essentially is that the best way for an addict, or those seeking recovery, the best shot they have is connection, and connection is best achieved in a residential treatment centre in the heart of a supporting and inclusive community.”

Darcy insists it would be a mistake to be disrespectful of the centre’s opponents. “The second any side starts saying we’re right and you’re wrong, you lose the battle and it turns into a flexing contest,” he says.

Scott has no trouble rejecting arguments the city failed to generate meaningful revenue from the $1 sale. “It has been proven… through a study done as part of Calgary’s 10-year plan to end homelessness, that if you take a high-flying addict off the streets and he stays sober for a year, it saves the taxpayers as much as $100,000,” he notes.

“That’s less demand on the justice system, less demand on first responders, less demand on health care, less demand on whatever services people require. And that makes perfect sense. If we have a 50-bed facility with the same success rate as (Calgary’s) Fresh Start has, which is 55 per cent, but for simple math let’s say 50 per cent… that would save the taxpayers $2.5 million.

It’s about giving people going through the ordeal their son endured a place to turn, a place to receive treatment, not judgment. Part of their mission is explaining that anyone, including young people from good families with supportive parents, can fall prey to addiction. Rehab is not always successful, but then what is?

The Oakes don’t mince words when asked what it was like trying to help their son during the endless cycles of addiction, detox, rehab and relapse that haunted the final five years of his life.

“It was torturous for us as a family,” Scott says. “It’s a vicious cycle. Whenever Bruce was in rehab or detox were the best times of our life during the last three or four years of his journey, because we always knew where he was and he had hope, we had hope. But the one thing we found out was that eight or nine days in detox, and sometimes just that and other times followed by those stints in treatment, that short-term stays are not nearly long enough. That’s why we’re committed to a facility that will let people stay for a year, two years, three years, whatever it takes.”

Bruce was in and out of detox eight or nine times.

Recalls his mother: “You’re only as happy as your unhappiest child. I was working part time as a nurse. I had to take time off to drag him somewhere to detox, clean out his apartment in Halifax… the first time he called us and said he was in big trouble, he got beat up, he was 22. But we’d had trouble before. Probably about five years.”

Diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a child, Bruce was impulsive and his drug use likely started with pot in high school.

But he was also charming and talented. Asked to describe his brother, Darcy, says: “Charismatic, life of the party, centre of attention, charming, win over the room, command the room, just all round lovable and fun. A joker.”

At the age of 25, Bruce, by then a heroin addict, died alone on the floor of a washroom stall of a sports bar not far from his Calgary apartment. Six days earlier, he had been ejected from Calgary’s Simon House program.

While not proposed as a “free” program, the recovery centre would be a viable option for addicts who have few resources. “It would be a sliding scale. If you can afford to pay, you pay whether it’s insurance or whatever, but no one is turned away because they can’t afford to pay,” Scott insists. “The ones who can’t afford are covered by a combination of fundraising and social assistance.”

With Manitoba and the rest of the country locked in a deadly opioid and meth crisis, the need for a long-term recovery centre is self-evident.

Notes Scott: “There were 4,000 people last year in Canada that died of opioid overdoses. I don’t know what the figures for the first quarter of this year in Manitoba are, but in 2017 it was 10 people a month dying of overdoses from January to March, so that’s one every three days. It would be shocking if, when the figures for the first quarter of 2018 are out, they’ll undoubtedly be higher. Then there’s the meth crisis.

“The most dramatic thing I always say when I speak in public is, when you think about it, with the lack of treatment available, we are leaving a generation of addicts out there to die… until treatment is made available to the countless addicts who can’t afford it, we’re going to go around in circles in this crisis.”

The family seems quietly confident Winnipeggers understand the need for a treatment centre like the one they’ve proposed. “The support that we’ve received has just been outstanding,” Scott says with a smile.

“We receive donations on a daily basis, and many of those in denominations of 20, 30, 40, 50 bucks, and I guess you’d refer to those as grassroots donations because if you’re giving 50 bucks or 20 bucks you have to think long and hard about whether you can afford it. We’ve added those up and it’s an extraordinary amount of money. Probably $60,000 to $70,000 in just grassroots donations, so we see that as the community voting on the need for this facility.”

Adds Anne: “And the emails we get, people wanting to volunteer (saying) ‘I don’t have any money to donate but what can I do to help?’ “

How to donate

From the start, Scott and Anne Oake have refused to pull any punches.

After their son Bruce died of a heroin overdose at the age of 25 in 2011, they decided to share his story.

From the start, Scott and Anne Oake have refused to pull any punches.

After their son Bruce died of a heroin overdose at the age of 25 in 2011, they decided to share his story.

“We were in Nova Scotia when we got the call Bruce had died in Calgary,” his father, Scott Oake, an iconic fixture on Hockey Night in Canada broadcasts, recalls.

“On the plane, on the way to get him, we wrote the obituary, and we were convinced there was no shame in the disease that had claimed his life and so we weren’t going to hide it. The first line of his obituary reads: ‘Tragically, Bruce lost his battle with addiction at the tender age of 25.’

“This was well before we even envisioned this kind of project. We just thought that anyone reading it and looking at this beautiful boy and who knew us, maybe they had a kid who was struggling, and if that gave them pause to think, ‘I gotta get things in order and find out more about my kid,’ that’s why we did it.”

To honour Bruce’s memory and prevent other tragedies, the Oake family is determined to build a $14-million, 50-bed long-term addictions treatment facility on the site of the shuttered Vimy Arena.

In the midst of a worsening opioid epidemic across the country, they believe a non-profit rehab facility in a supportive, residential area can save lives. You can help by visiting bruceoakerecoverycentre.ca or bruceoake.ca and clicking the donate button.

With the rezoning in progress, the Oakes can’t launch their capital fundraising campaign because the property isn’t theirs. “We could but it would be disingenuous and if we did that the people who are opposed to this facility would be up in arms yelling, ‘See, it’s a done deal. We knew it.’ So the best course of action for us is to wait for final approval from city council.”

If things go according to plan, the Oakes will be able to break ground on the project next August, the morning of what would have been Bruce’s 34th birthday, and the doors would open in 2020.

It would definitely be a family’s dream come true, but, sadly, nowhere near their hearts’ desire.

“Nothing will bring him back,” Anne reflects quietly.

“We would give anything we have for just one more day with him,” Scott concludes.

doug.speirs@freepress.mb.ca

Doug has held almost every job at the newspaper — reporter, city editor, night editor, tour guide, hand model — and his colleagues are confident he’ll eventually find something he is good at.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.