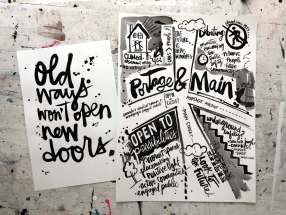

An open-and-shut case Winnipeg architect Brent Bellamy isn't a candidate in the civic election, but he's leading the charge on the ballot question; he believes removing the concrete barriers at Portage and Main will be transformative for the city

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/09/2018 (2744 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There’s a pleasant buzz at the coffee shop just after noon when Brent Bellamy settles down at a back corner table.

If he was in advocate mode, he might share some of his usual fun facts. He might point out that just two blocks away, at Portage and Main, more than 15,000 people are working, living and breathing life into the downtown. But this is a more casual conversation.

And so, the chat begins and it quickly becomes clear the creative director at the architectural firm Number TEN Architectural Group, board chair of Centre Venture and periodic Free Press columnist, has become busier than ever.

“Portage and Main has been taking over my life,” he says, with a what-can-you-do shrug.

This was not how he imagined the year would turn out. Yet here he is, in late summer 2018: the city is slouching towards a civic election in which its most famous intersection has become a starring issue, a political hot topic.

Bellamy has emerged as one of the most visible champions of opening it up. He writes about it. He talks about it, a lot, giving formal quotes to media and more impromptu sessions to Winnipeggers.

In August, he joined a core group of about a dozen people as Vote Open Winnipeg. Last week, he went on the radio to publicly tangle with North Kildonan Coun. Jeff Browaty, among the most vocal opponents of taking down the barriers.

Since July 1, he has tweeted about the intersection nearly 75 times — a figure that does not even include the lengthy debates he’s waged with critics. Sometimes, he thinks about just setting up a booth near a suburban shopping strip, and inviting people to ask him questions.

Why?

“I hear that a lot: What do you gain from this? I don’t gain anything. I feel like I’ve been given a platform to talk about it, so it’s almost my duty to do that. I wish it wasn’t. I get mad every day — that we’re voting about it. I don’t gain from it in any way, other than this is my city I want to live in for the rest of my life, and I want to be in love with it.”

To be clear, Bellamy is not the only prominent advocate for opening the intersection. Or the longest-serving, for that matter.

Outgoing Fort Rouge-East Fort Garry Coun. Jenny Gerbasi has tried to advance the idea for years (she was also the only councillor to vote against sending the matter to a referendum). So, too, have other downtown boosters.

Yet this summer, as the debate over opening Portage and Main became enflamed, Mayor Brian Bowman, who had once so brightly made it a campaign promise, has since retreated from being too publicly connected with it, saying only that he will respect the will of voters. And into that void has come Bellamy who has emerged as Team Open’s most visible proponent.

“It’s so divisive politically, people don’t want to talk about it that much,” Gerbasi says. “I’ve tried to do my part on it, but… it’s hard to get it in the public dialogue and agenda. Brent has done a lot to do that.”

It’s hard for Bellamy to pinpoint when he first became enchanted by Portage and Main’s potential. The intersection, closed to pedestrians in 1979, has been that way for most of his life; but at some point, his perspective changed.

He grew up in North Kildonan, in a family steeped in education: his mother a teacher, his father an artist for the school division. (In the most Winnipeg twist of all, Browaty was a student at the school where his mother taught.)

Bellamy inherited his dad’s artistic talent, and architecture seemed the most practical outlet for that.

He doesn’t recall the intersection being discussed in his university courses, though he thinks that may have since changed. But every weekday as a student, he’d drive through it on his way to classes at the University of Manitoba.

It was around this time that he started travelling, a lot. He interned in Israel. His passport logs visits to more than 60 countries. In the sprawl of Tokyo, he began to see new intersections between possibility and practicality.

“As I learned more about what makes a great city, it just became this weird thing that needed to be different,” he says. “The cities I fall in love with don’t have that weird condition of concrete walls pushing people away.”

Those realizations sparked a lifelong interest. He wanted to understand why the intersection had been closed in 1979; he wanted to understand what else could be done.

One turning point came in 2004. That year, then-mayor Glen Murray convened a design competition, inviting architects the world over to submit ideas to transform the windy intersection. Bellamy contributed a design.

That design was “young architect silliness,” he tweeted later, featuring a walkable platform that soared over the street. “If I was doing it today, I wouldn’t ever do a design that pulled people off the sidewalk,” he says.

But maybe the seeds were planted. Nine years later, in September 2013, Bellamy penned a Free Press column entitled Let Portage and Main breathe. The column — a hit among Winnipeg’s young urbanists — was widely shared.

One of them was Brian Bowman — then working as a privacy lawyer — who tweeted a link to the article with the praise “#BoldWinnipeg thinking.” Eight months later, Bowman entered the mayoral race.

It was the first time in more than a decade that a mayoral candidate had made the intersection an election issue.

“It was really exciting to see that city-building issues were something that the electorate was becoming really excited about,” Bellamy says. “It felt like my writing and advocacy, and others’, were gaining traction.”

To many supporters, Bellamy is one of the most unshakable champions. To critics, he is something else. Browaty has called pro-open advocates “elites” and “small-interest groups,” drawing strong objections from Bellamy.

Outside the boundaries of this issue, their relationship is not so contentious. Bellamy says Browaty is a “funny guy” who has jokingly teased him about the issue; Browaty says Bellamy is “consistent, I’ll give him that.”

Consistency is a virtue. Clever, persuasive tweets don’t hurt, either. But will either be enough for this mission to discover what’s beyond the concrete barriers in the heart of the city?

“It’s very hard to do a city-wide campaign about a local issue,” Gerbasi says. “That’s what’s making this so difficult. Brent Bellamy sounds great on Twitter, but are people going to read that? What percentage of people are on Twitter?”

In a perfect world, Bellamy will soon be standing at Portage and Main waiting for the red light to change to green so he can walk across the street. But there is the matter of the ballot question that needs to be answered on Oct. 24 by the people he shares this city with.

“I understand the realities, the likelihood of what this is going to be in the end,” he says. “It’s an important debate to have. Not just about Portage and Main, but it’s a really rare opportunity to talk about city-building. When are we ever going to vote on a city-building issue again?

“Probably never,” he adds, and then laughs. “Hopefully never.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.