Poverty to prosperity First Nations in other provinces have used a helping hand from tax advantages to establish urban reserves producing economic growth, transforming Indigenous lives and benefiting surrounding communities

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/10/2018 (2601 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

MILLBROOK, N.S. — This bustling little suburb of Truro has a modern hotel, restaurants, a gas station, furniture store, multiplex cinema, RV sales and service centre and some of the tidiest, most well-kept homes in the province.

Kapyong Barracks

Seven First Nations will take over Kapyong Barracks with the intention of creating an urban reserve. The barracks comprise 160.6 acres and, until demolition began earlier this year, 40 buildings.

Seven First Nations will take over Kapyong Barracks with the intention of creating an urban reserve. The barracks comprise 160.6 acres and, until demolition began earlier this year, 40 buildings.

The First Nations:

• Long Plain

• Brokenhead Ojibway

• Peguis

• Roseau River Anishinabe

• Sagkeeng

• Sandy Bay

• Swan Lake

MANITOBA’S URBAN RESERVES

There are currently ten urban reserves in Manitoba. They are:

Opaskwayak Cree Nation (adjacent to the Town of The Pas)

Swan Lake First Nation’s urban reserve land (within the Rural Municipality of Headingley and adjacent to the City of Winnipeg)

Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation’s urban reserve land (adjacent to the City of Winnipeg)

Sapotaweyak Cree Nation’s two parcels of urban reserve land (both located within the Town of Swan River)

Nisichawaysihk Cree Nation’s urban reserve land (within the City of Thompson)

Birdtail Sioux First Nation’s urban reserve land (located within Foxwarren in Prairie View Municipality)

War Lake First Nation’s 40 parcels of urban reserve land (located in Ilford)

two urban reserve lands belonging to Long Plain First Nation (one adjacent to the City of Portage la Prairie and one within the City of Winnipeg).

— Government of Canada

It has a workforce as diverse as its customers.

On the other side of the country, the area known as Westbank, near Kelowna, B.C., features a similar array of businesses, from a Mark’s clothing store to a Home Depot, Winners and 543 other companies.

What both don’t have is just as revealing as what they do; there are few outward signs of either community’s true nature.

Millbrook and Westbank are urban reserves.

Across the country, First Nations are establishing urban reserves, areas that are within or adjacent to cities and enjoy some of the tax advantages of regular reserves, but offer the opportunity for self-sufficiency lacking for many remotely located First Nations. Manitoba, it seems, has some catching up to do, with 10 relatively nascent urban reserves, and only two directly within its largest city, Long Plain and Peguis. By comparison, Saskatoon alone has six.

In mid-August, Peguis broke ground on its urban reserve, a $30-million office/residential/retail complex on Portage Avenue. Earlier this year, Ottawa signed an agreement in principle with seven Treaty 1 First Nations that will pave the way for an urban reserve on the former Kapyong Barracks site on Kenaston Boulevard.

Tax advantages are a source of resistance for some non-Indigenous Canadians and business groups, such as the Canadian Tax Federation, who see the urban reserve as offering an unfair advantage to non-reserve neighbours. Those tax advantages aren’t nearly as great as they seem.

As well, economic analyses of existing urban reserves, such as Millbrook and Westbank, suggest that not only do they provide a long-awaited economic foothold for band members, they contribute significantly to the economic well-being of their respective cities and provinces, as well as reversing the flow of money between the Canadian government and the First Nations.

“Wherever you see these developments, they end up making a positive contribution to the First Nation, to the city and to the province,” said Damon Johnston, president of the Aboriginal Council of Winnipeg. “It’s a win-win situation.”

A study of Westbank First Nation, which entered into a self-government agreement with the federal government in 2005, shows the area’s total annual tax contribution to federal and provincial coffers grew from $53.1 million in 2005 to $107.9 million in 2015. Those figures are inflation-adjusted to 2015 dollars.

“It should be noted the fiscal benefits to Canada and B.C. are underestimated because they only include income, sales and corporate provincial and federal tax revenues,” says the analysis by Fiscal Realities Economists of Kamloops, B.C. “Despite this caveat, the cumulative fiscal benefits from Westbank self-government are even more impressive.”

More interestingly, the analysis shows that federal transfers to Westbank pale in comparison to federal taxes collected: over the same period, Westbank generated $586 million in federal taxes compared to earning $90 million in federal transfers, again in constant 2015 dollars. Another report, also by Fiscal Realities, estimates self-government has created 3,400 jobs in Westbank and generates $36.3 million annually in off-reserve spending by band members. Of those 3,400 jobs, 1,190 were filled by reserve residents. Assessed property values in Westbank are nearly a billion dollars in residential, $380 million in commercial and $5 million in industrial.

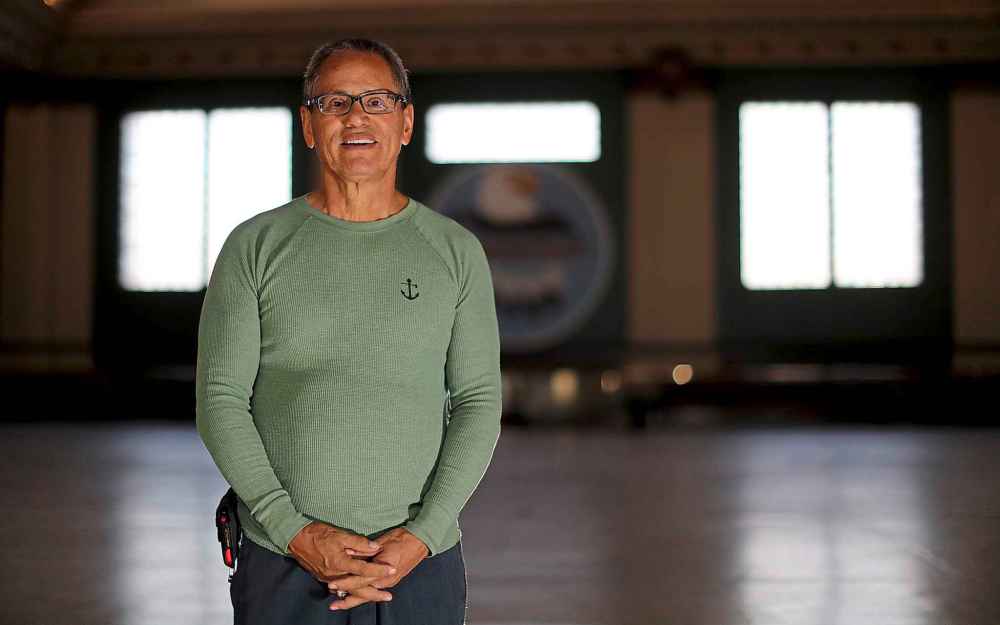

“People drive through here all the time and have no idea,” said Sharon Bond, who owns Kekuli Café in Westbank. “They ask, ‘Is this an urban reserve?’ and they’re like ‘Wow!’ This is nowhere near what they thought.”

Under its self-government model, Westbank issues its own building permits, occupancy permits and business licences, Bond said. She said Westbank is very prompt in issuing permits. “With West Kelowna, it can be a month or more, but with Westbank it’s like a week. They’re very well-organized.”

Westbank First Nation Chief Roxanne Lindley said the experience shows that given a chance, Indigenous Canadians can take their place in the economy, for the good of both the First Nation and the greater community.

“Our members fought hard to get where we are today,” she said. “Without the vision, drive and strength of our people, the success of our self-government agreement with Canada would not have been achieved.

“We structured our laws to accommodate development. Our members understand the need to work and profit, and this spirit has led our drive to develop.”

Lindley said in 2017, Westbank experienced $45 million in construction, of which $38 million was residential, $6 million was commercial and $1 million was institutional. As well, Westbank issued $500 million in building permits during the past 10 years, and for the fiscal year ending in 2018, $14 million in property taxes were collected from 4,310 property owners. She said this entrepreneurial spirit helps drive investment, Indigenous and otherwise, in the community.

“As a self-governing nation, we can cut through red tape and provide an effective and efficient system that gives confidence and security to developers and residents.”

Two of those developers are Anthem Properties and Churchill International Property Corp. Both are from Vancouver and each entered into joint ventures with Westbank on developments totalling 1.45 million square feet in retail space.

In Saskatoon, the creation of Canada’s first commercial urban reserve 30 years ago — by the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation — has been followed by five more, with a seventh in the works. The benefits to the city, economically and socially, have far outweighed any negative perceptions, said Gilles Dorval, that city’s director of aboriginal affairs.

“Any time we can create more businesses in our city, it’s going to have economic spinoffs for the entire community,” Dorval said.

As with Westbank, businesses locating on reserve lands have not all been Indigenous, he said. As well, he said the city is starting to notice some First Nations are buying land and deciding against pursuing reserve status, instead developing the land outside the provisions of the Indian Act. These urban holdings, as they’re called, are subject to the same city bylaws, taxation and zoning as other properties.

Having its Indigenous residents participate in the economy has not only allowed the city to grow, it creates a stronger sense of pride and acceptance of people from all backgrounds, Dorval said.

“If you have a stronger mix of diversity overall, everybody is going to experience a better quality of life,” he said.

That all these urban reserves — in Westbank, Saskatoon, Vancouver, Millbrook, and elsewhere — are not yet reflected in Manitoba’s fledgling urban-reserve reality, is a large part of why Manitoba’s Indigenous population is at a disadvantage to those in other provinces, Johnston said.

“In Manitoba, we’re economically and socially behind virtually every other province and territory,” he said.

Millbrook First Nation Chief Bob Gloade, in a video on the success of the reserve’s retail power centre, said location is everything in economic development, and the development, located on Highway 102 between Halifax and Truro is no different.

“Within a three-hour drive, there’s approximately 1.3 million residents,” he said.

Highway 102 is an important connector between Halifax and the rest of Canada. Almost all road traffic between into and out of the city passes the power centre.

“The long-term plan for our community is sustainability and providing opportunities for all generations of our members, from our youth to our elders,” Gloade said. Profits from the power centre are used to finance employment training and economic development for the nation.

“I’m very proud that the band’s success is everybody’s success,” said band administrator Alex Cope, also in the same video. “Almost every essential service provided has been supplement by the economic development success of the Millbrook band. We look after our people.”

Johnston urges non-Indigenous Canadians to give the urban reserve model a fair shake and recognize the Indian Act stripped Indigenous people of the ability to prosper. What the Indigenous community really wants, he said, is a chance to end its dependence once and for all.

“As Indigenous people we were dispossessed of our wealth,” he said. “We don’t have the money or the equity for these kinds of developments, so if there can be some kind of incentives, it’s a doorway to economic freedom.”

The Indian Act created the reserve system, but also prohibited private ownership of land on reserves. Without that base upon which to build equity, Indigenous Canadians were deprived of a means to generate wealth, Johnston said. That many reserves were located in remote, inaccessible communities, and some were removed from fertile agricultural lands and placed in, essentially, wasteland further hampered efforts to prosper. Part of the area now known as West St. Paul just north of Winnipeg, for instance, was promised as reserve land under Treaty 1.

Bond said as an Indigenous business owner working and living on a First Nation, her personal income is exempt from taxes, but her business doesn’t enjoy much, if any, advantage; her business pays provincial and federal corporate income tax, she pays property taxes through her lease payments and struggled to establish herself just like any other businessperson in Canada.

“People say this was all bought and paid for by the federal government, but no, I had to get a loan and work hard just like anyone else,” she said. Kekuli employs about a dozen staff, all Indigenous. She is bound by the same labour laws as all B.C. businesses and, like any other business, she pays the employer’s portion of employment insurance premiums and Canada Pension Plan contributions.

Indigenous Services Canada (the former Indian and Northern Affairs department) confirms the tax advantages are often overstated. Section 87 of the Indian Act, which lays out specific tax exemptions enjoyed by status-bearing band members working and living on a reserve, specifically excludes corporations, even corporations owned by Indigenous entrepreneurs.

Going forward, Bond has plans to franchise, taking her bannock, coffee and Indian taco (her term) creations across the country, and already has another location, in Merritt, B.C. She’s not limiting her expansion to on-reserve locations, either.

“We hope to be the ‘Indian’ Tim Hortons.”

The 2016 Canadian Census provides further evidence of Westbank’s prosperity: its median household income ($70,561) is average for the area around Kelowna. It’s not the highest (Okanagan East, at $85,504), but it’s also nearly $20,000 higher than the lowest (Okanagan Indian Band, at $50,987). Westbank has slightly higher unemployment (8.9 per cent) than surrounding areas, but of its 4,045 people in the labour force in 2016, 3,715 had jobs.

Westbank is a hotbed of small business; of the 287 companies with employees, 245 employ 19 or fewer people, according to the Business Patterns Survey conducted in 2017 by Statistics Canada.

The rules for running urban reserves are startlingly similar to the rules for any land transaction: in the case of a First Nation establishing a presence on non-reserve land, any land sales must be on a willing-seller, willing-buyer basis. The exception is when federal lands are declared surplus, such as Winnipeg’s Kapyong Barracks. Whether the federal government is paid for such land is situation-specific. The land, once acquired, is either held in fee-simple status by the band or turned over to the federal government as reserve land. In the case of Westbank, its self-government agreement turns the band into a municipality like any other.

When needed, First Nations negotiate service agreements with local municipalities to cover services such as garbage, wastewater and water. These are typically negotiated at less than the prevailing property taxes would otherwise be, on the premise that the First Nation, not the municipality, is providing a portion of the services the municipality otherwise would.

Indigenous Services Canada spokesman William Olscamp said the details of each agreement are negotiated between the First Nation and the municipality. In the case of Peguis First Nation and its urban reserve on Portage Avenue, the service agreement was for 80 per cent of the comparable property taxes, with the provincial government compensating the city for the remaining 20 per cent.

University of Manitoba economist Gregory Mason agrees urban reserves provide promising potential to help Canada’s Indigenous community prosper.

“A hundred years ago, governments created the reserve system away from planned urban development to ensure Indigenous Canadians could continue their traditional way of life,” he said, “but the effect was to create rural ghettos, and now most reserves are poorly positioned to participate in today’s economy.

“It’s really about helping to rebalance the historical inequity.”

He said the land values in question, particularly in areas in large cities, should help allay fears of any poverty in remote reserves transferring into the city.

“If you look at Kapyong Barracks as an example, that’s a large swath of high-value land, so the owners (a group of seven First Nations) are going to be very interested in getting the maximum value out of that land.”

Part of that, Mason said, hinges on the form of financing used to develop the lands.

“If it’s low-interest loans or loan guarantees from the federal government, the danger is there will be ill-conceived developments,” he said, particularly on a large parcel such as Kapyong Barracks in Winnipeg.

A shopping centre that competes with the Seasons Outlet Mall less than a kilometre away, for instance, would be a bad idea.

“If it’s private investors, they’d be very interested and involved in ensuring the organization develops the area in a way that’s compatible.”

On that point, Johnston and Mason concur. “You have to have some skin in the game,” Johnston said. “You have to have a market analysis done, so you can know what’s going to work.”

Mason would like to lose the word “reserve,” however. “The term ‘reserve’ has all sorts of negative connotations, so while they’re not really municipalities, we should come up with some other name.”

Mason and Janice Barry, an urban planning professor at the University of Waterloo and an adjunct professor at the University of Manitoba, both said co-operation on land-use planning with surrounding municipalities is a must for an urban reserve to succeed.

Barry said the successful urban reserves are those that are “contiguous with the rest of the city. You hardly know where the municipal boundaries stop and the urban reserves begin.

“That’s what we hope for, processes around long-range planning that support this kind of collaboration.”

She said early in the process of negotiating co-existence, urban reserves and their surrounding city should agree on some “higher-level thinking” around what it means to be self-governing, recognition of the city’s authority over planning and of the authority given to the First Nation as original occupants of the land. She said that kind of symbolic beginning helps set the stage for other negotiations to follow.

“It is a government-to-government relationship, or it ought to be, so there needs to be agreement on how the First Nation should be engaged when Winnipeg is engaged in 20-year planning. There should be true mutual dialogue and not just about day-to-day planning and zoning,” she said.

That kind of dialogue has paved the way for Saskatoon’s success, Dorval said. Early in the process, the First Nations and the city negotiated the terms of co-existence, including the fees for services and bylaw compatibility. As a result, the reserves look no different than any other part of the city.

On the other side of the country, in Millbrook, N.S., the success is similar. In addition to its power centre on the highway just outside Truro, the Mikmaq First Nation governs reserve land in Cole Harbour, outside Dartmouth, and in Sheet Harbour and Beaver Dam, all in Nova Scotia. In Cole Harbour, the band operates two apartment buildings and leases a building to General Dynamics, an American aerospace and defence corporation.

The band operates a multimillion-dollar rainbow trout farm, a fishery, tobacco sales and a small gaming component. As well, it operates a community wind farm.

Again, government transfers form only a small part of the band’s $49 million in revenues, which return nearly $5 million to band members, pay $8 million in salary and benefits and fund nearly $4 million in local and post-secondary education. The band returns $20 million to the community in sales, with 80 per cent spent in the local area. Those numbers don’t include salaries paid by companies operating on the reserve, nor spending by residents, who are both Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

Westbank’s Lindley said the success of the First Nation has been a source of pride for band members — including winning the 2015 national Communities in Bloom title for communities with population between 20,001 and 50,000 residents. The nation invests in housing, sports facilities, language and cultural programs, a new youth centre and in safety and urbanization.

As well, an economic development commission advises band councillors and is working to build an environment that will provide employment for youth and inspire the next generation of entrepreneurs.

“I am very proud of our members and our community,” he said.

kelly.taylor@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.