Manitoba’s last hanging Drunken rage led to fatal shooting of veteran Winnipeg police officer in 1950; Henry Malanik’s trials, appeals and stays of executions came to an end 70 years ago at Headingley Jail

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/06/2022 (1361 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

His lawyer argued he was so drunk he had no memory of the events that took place on that fateful night.

But the facts remain. On the evening of Saturday, July 15, 1950, Henry Malanik, 48, shot and killed Winnipeg police Det.-Sgt. James Edwin (Ted) Sims, 42, in a home at 19 Argyle St. in Point Douglas.

Malanik was tried, convicted and ultimately hanged 70 years ago — on June 17, 1952 — giving him the dubious distinction of being the last person executed in Manitoba.

There is no way to romanticize the awful events of that horrific night. Somewhere in the police archives there is surely a faded file filled with black-and-white crime scene photos that paint a sombre and bloody portrait of the murder and mayhem Malanik committed.

Sims was a rising star in the police, a detective who was active in the community, respected by his colleagues and loved by his family. Although the tides on capital punishment in Canada were already tumultuously turning, there was little sympathy for Malanik and the resounding sentiment was that anyone responsible for the murder of a police officer should come to the end of their life at the end of a rope.

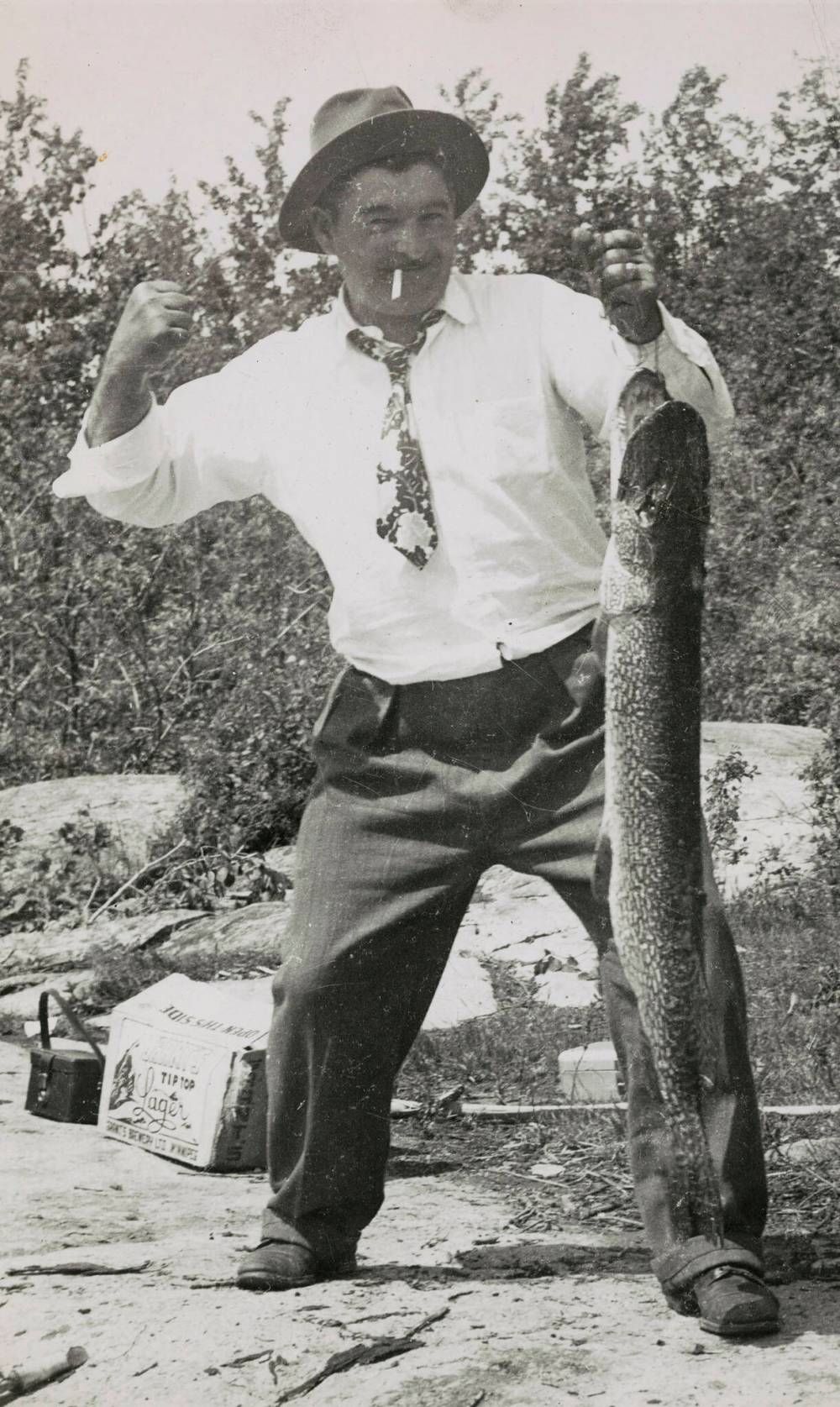

Although he wasn’t a hardened career criminal like the often desperate cop-killers who typically make headlines for their heinous acts, Malanik, a plumber by trade, wasn’t without his problems.

Born in Ukraine, he came to Winnipeg as a child in 1912 and had only a Grade 4 education. He was convicted of several break-and-enters at age 17, but stayed out of trouble until 1950.

That year, only a few months before the fatal shooting, Malanik and his best friend, Adolph Kafka, became involved in a bitter love triangle involving Kafka’s wife; a drunken brawl with gunfire presumably ended their friendship. Both men pleaded guilty to discharging firearms and each received $50 fines.

In a twist of fate, the guns seized in the fracas were returned to Malanik by the police; one was the shotgun he used to kill Sims.

On the night of the shooting, Malanik attended a wedding where he consumed a significant amount of liquor, including a home brew, to the point he was kicked out of the event for fighting with the accordion player from the band Stan and His Range Riders.

Emboldened with whisky courage, Malanik climbed in his 1941 Dodge and drunkenly drove to his ex-friend’s home a few blocks away. There was a fight, and he ended up stabbing Kafka three times with an army dagger before fleeing, according to reports from the time.

The Headingley hangings

(By execution date, name, age and crime).

Sept. 3, 1931: John Strieb, 45, triple murder

Feb. 1, 1932: James McGrath, 24, killed wife, 19, with butcher knife

Feb. 2, 1932: Joseph Veroski, 34, robbed and murdered traveller

Feb. 3, 1932: Andrew Bodz, 56, beat his wife to death

(By execution date, name, age and crime).

Sept. 3, 1931: John Strieb, 45, triple murder

Feb. 1, 1932: James McGrath, 24, killed wife, 19, with butcher knife

Feb. 2, 1932: Joseph Veroski, 34, robbed and murdered traveller

Feb. 3, 1932: Andrew Bodz, 56, beat his wife to death

July 12, 1933: Fred Stawycznyj, 45, murdered his illegitimate infant child

Sept. 1, 1933: Peter Piniak, 26, murdered Martha and Eddie Squarok

May 21, 1934: Julian Komarnicki, 35, axe murder

May 22, 1934: Andrew Orichowski, 58, axe murder of wife

Feb. 12, 1935: George Jayhan, 34, shot and killed Winnipeg police officer

Aug. 21, 1936: John Pawluk, 49, murdered his wife

Nov. 20, 1936: Ian Murray Bryson, 22, shot Const. Charles Gillis

Jan. 27, 1938: Peter Kidala, 36, axe murder

Feb. 16, 1939: William Kanuka, 40, double murder and attempted robbery

Feb. 16, 1939: Peter Korzenowski, 28, double murder and attempted robbery

Feb. 16, 1939: Dan Prytuula, 31, double murder and attempted robbery

May 8, 1941: Nick Zhiha, 19, robbed and threw man from a train

July 24, 1944: Albert Victor Westgate, 43, strangled woman

Feb. 8, 1946: Baldwin Jonasson, 47, murdered 16-year-old girl

April 16, 1948: Lawrence Deacon, 35, murdered taxi driver

Nov. 5, 1948: Clarence George, 33, murdered his female lover

Nov. 19, 1948: Michael Angelo Vescio, 22, sexually assaulted and murdered two boys

May 9, 1950: Camille Allarie, 32, shot his husband-and-wife employers

May 9, 1950: William Lusanko, 20, suffocated woman during robbery

Jan. 17, 1951: Walter Stoney, 39, murdered his wife

June 17, 1952: Henry Malanik, 48, shot Winnipeg detective during a domestic dispute (Manitoba’s last execution)

Source: Canada Death Penalty Index

Two uniformed officers arrived at the scene and took Kafka to the hospital, where he was treated and released.

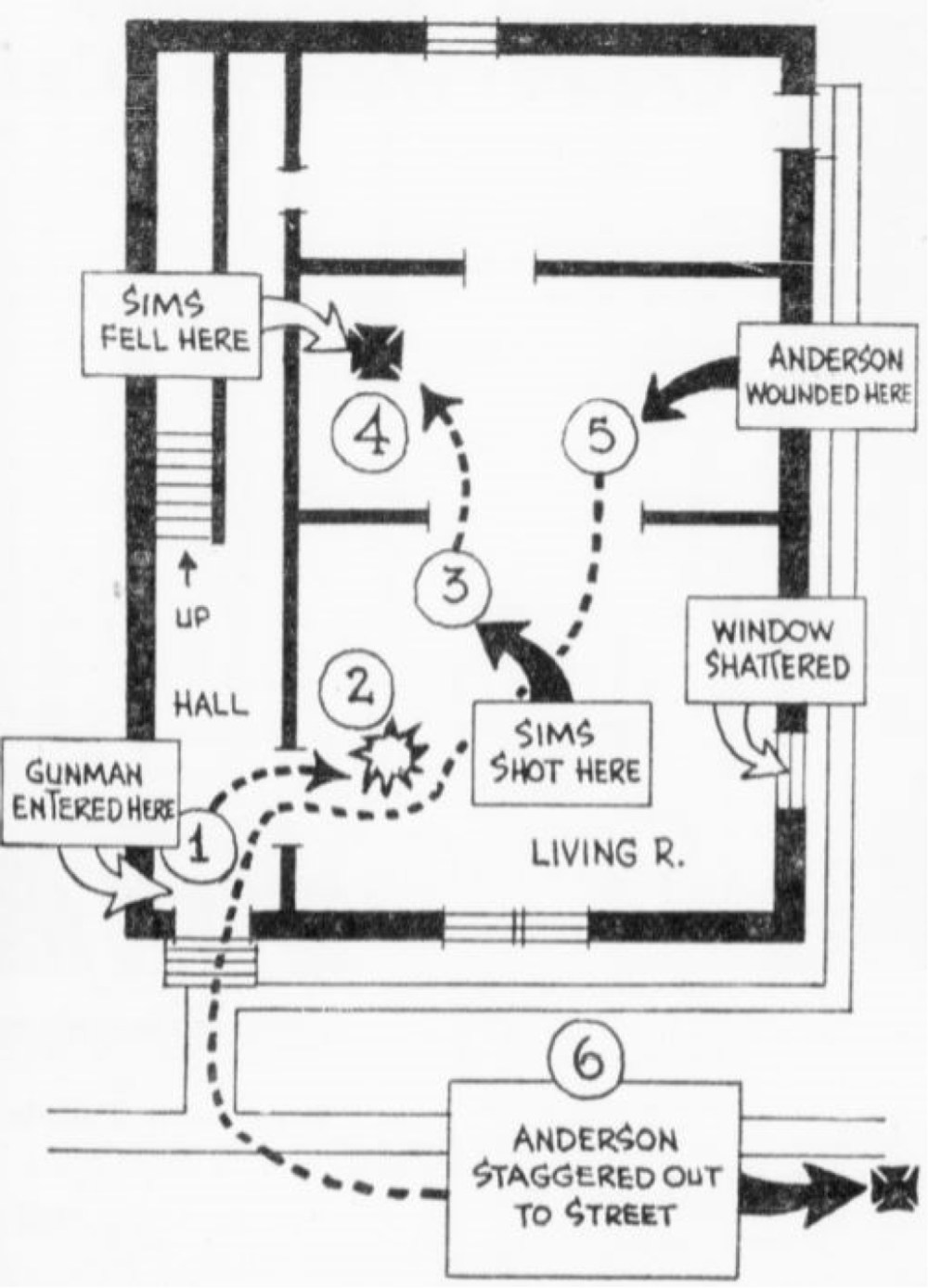

Three detectives, led by Sims, also arrived to investigate. While interviewing the remaining occupants — Kafka’s wife, her parents and someone renting a room — Malanik burst into the home in a fit of rage with a 12-gauge shotgun, which he had hidden away nearby. The unarmed Sims pleaded with him to drop the gun.

“The detective cried, ‘Don’t be a fool, man. Put that gun away,’” the Winnipeg Free Press reported.

Malanik hesitated a second before pulling the trigger, blasting Sims with both barrels in the stomach at point-blank range. A second officer, acting detective William Anderson, was wounded. The third, acting detective John Peachell, returned fire.

Malanik was shot three times, with wounds to his left hand, shoulder and hip. He was, reportedly, laying on the floor next to Sims, sobbing and repeatedly begging the officer not to die.

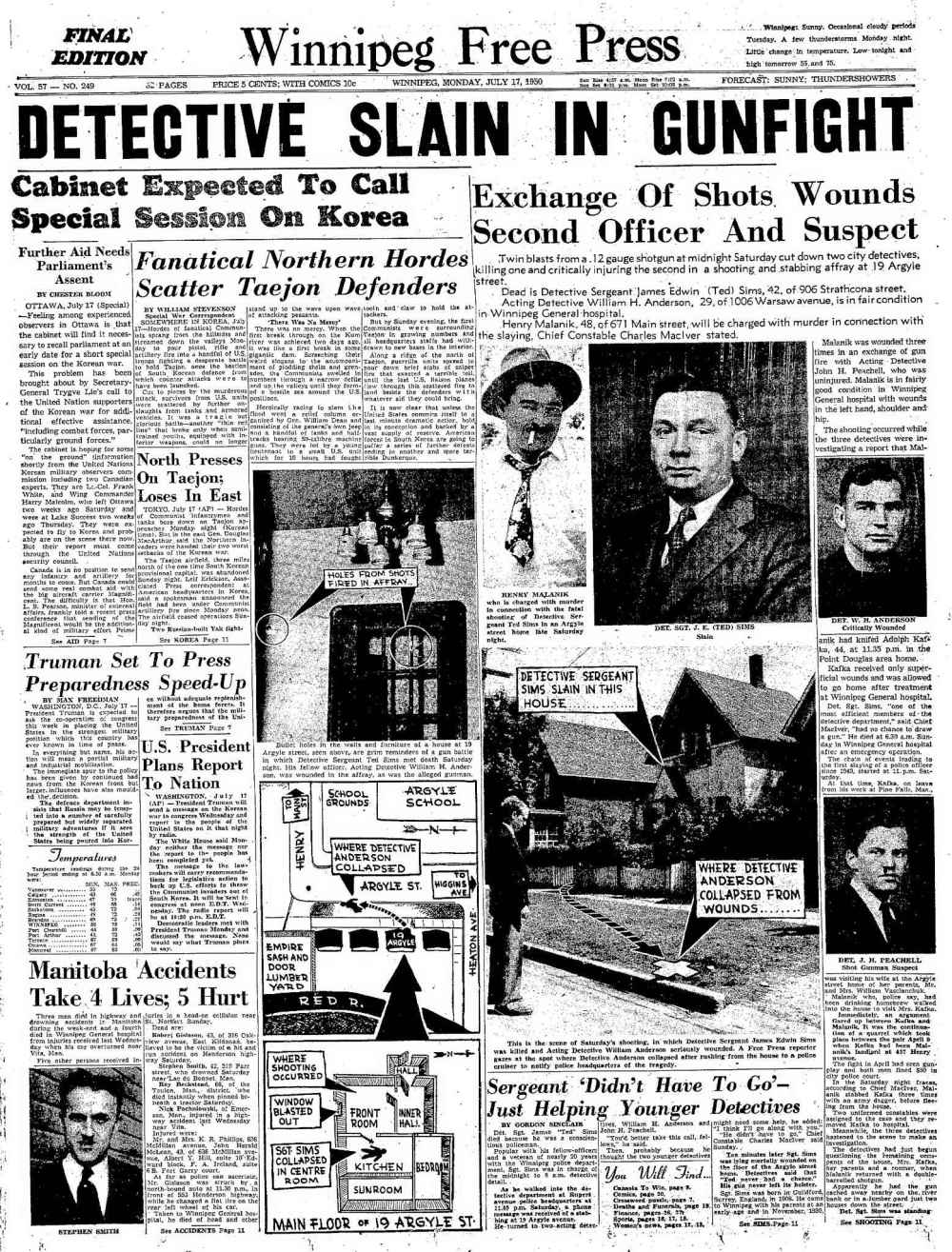

“DETECTIVE SLAIN IN GUNFIGHT” screamed the Free Press front-page headline on Monday, July 17, accompanied by the underline “Exchange of Shots Wound Second Officer and Suspect.”

The front-page coverage was extensive, featuring photos of the slain officer, detectives Anderson and Peachell and Malanik. It also included a photo of the bullet holes from inside the house, a photo of a Free Press reporter gazing at the spot outside the house where the wounded Anderson collapsed and a drawing of the home’s layout, marking where the shooting occurred, where a window was blasted out and where Sims collapsed.

Sims, a 20-year veteran, was in charge of the overnight detective detail that night. When the chaos ended, he became the first slain Winnipeg officer since 1940.

The Free Press set the stage in a second front-page story:

As he walked into the detective department at Rupert avenue police headquarters at 11:45 p.m. Saturday, a phone message was received of a stabbing at 19 Argyle avenue.

He turned to two acting detectives, William H. Anderson and John H. Peachell.

“You’d better take this call, sadfellows.”

But then, thinking they would need help, he decided to join them.

Sims, hailed as “one of the most efficient members of the detective department,” according to Chief Const. Charles MacIver, “had no chance to draw a gun.”

MacIver went on to say Sims was a great loss for the force.

“He had a marvellous memory and knew every member of the city’s underworld after he had once seen them. He never forgot a criminal’s face or his history.”

Sims died the following morning, but Anderson survived. Malanik made a full recovery.

It was first believed Anderson was originally caught by the spray from the shotgun blast that killed Sims.

According to an article about the murder of Sims on the Winnipeg Police Museum’s website, former Winnipeg police officer and historian Jack Templeman wrote that it was later determined Anderson was shot accidentally by another officer, Const. J. Slot.

At the time, rookie officers were not permitted to carry guns, but it was suspected Slot had a pistol in his possession and, mistaking the plain-clothes detective for a suspect, shot him in the neck and abdomen when responding to the call for backup. Slot was subsequently fired for breaching regulations and falsifying his report.

There was little doubt, however, who shot Sims.

Malanik’s lawyer, Harry Walsh, tried unsuccessfully to have him tried for manslaughter, arguing his client’s extreme drunkenness at the time meant he was unable to form the intent for murder.

One witness, Dr. Gordon Burland, who treated Malanik at the Winnipeg General Hospital (now part of Health Sciences Centre), told court he could smell alcohol on Malanik’s breath and that he was loud and difficult to control.

However, at the conclusion of the four-day trial in October 1950, the jury took just 40 minutes to return with a guilty verdict. The front-page Free Press headline summed it up succinctly: “Malanik To Die Jan. 17.”

A second trial was ordered after a successful appeal. Two appeal judges quashed the murder conviction, reducing it to manslaughter. The other three judges called for a new trial.

Malanik took the stand in his defence in May 1951, saying he had blacked out due to excessive drinking at a wedding party. The next thing he remembered was waking up on a stretcher.

“How can I say if I remember anything or not?” an agitated and tense Malanik told court. “I have been in the death cell for nine months. I hardly remember if I’m even existing.”

The jury deliberated for nine hours before returning with a murder conviction. He was sentenced to be hanged at Headingley Jail. His lawyer appealed, again arguing Malanik couldn’t form intent due to excessive drunkenness.

In total, Malanik was granted five execution stays before his appeals ran out.

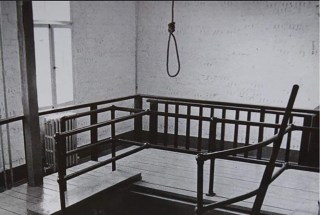

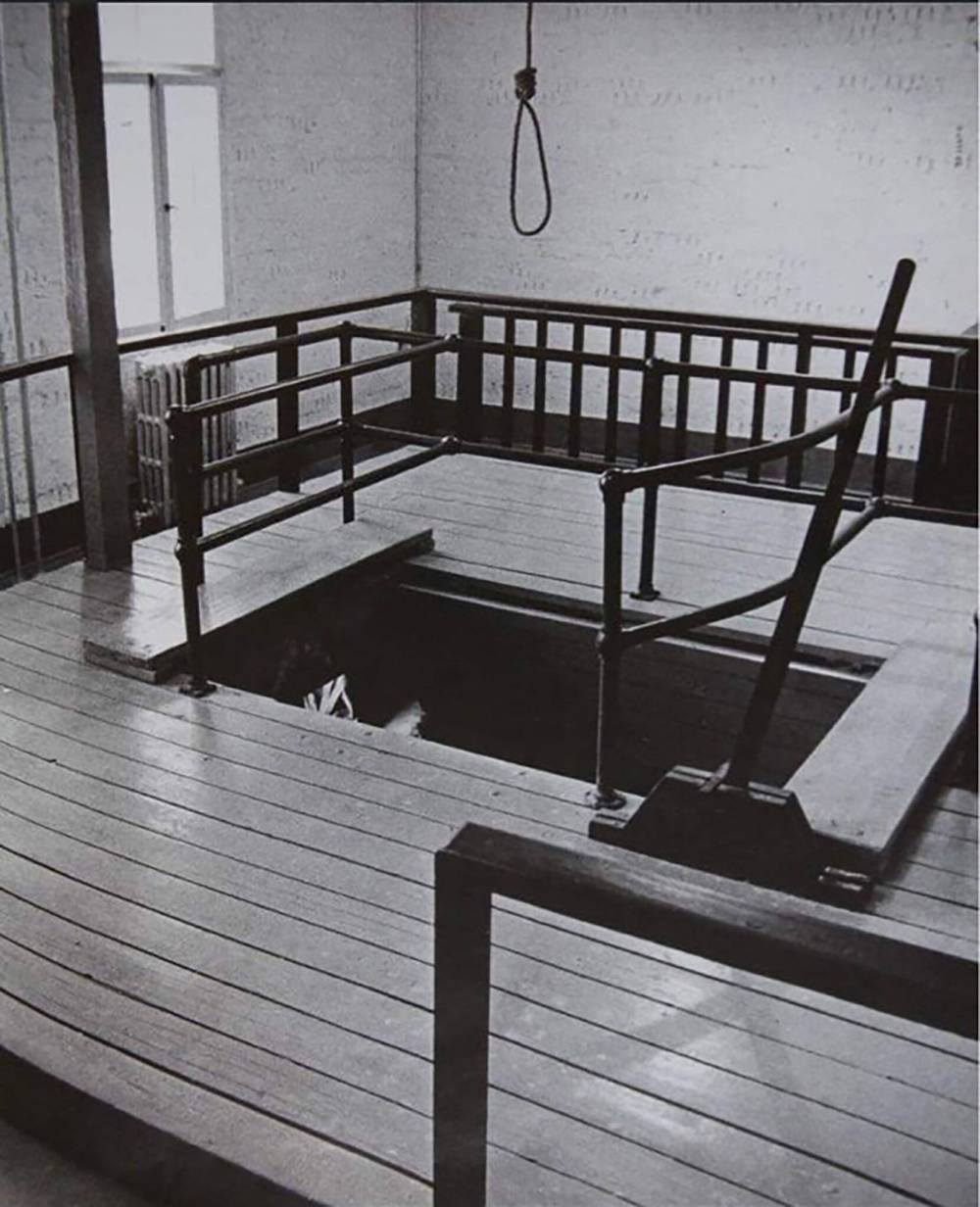

Nearly two years after the Argyle Street shootout, he was hanged at Headingley shortly after 2 a.m., on June 17, 1952.

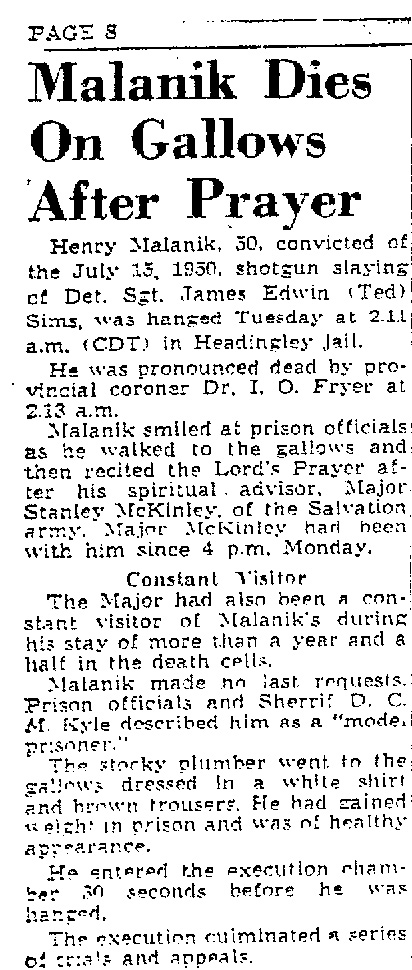

The death merited a 16-paragraph story on Page 8 of the Free Press, under the headline, “Malanik Dies On Gallows After Prayer.”

According to the story, Malanik entered the execution chamber 30 seconds before he was hanged.

He smiled at prison officials as he walked to the gallows and then recited the Lord’s Prayer with his spiritual adviser, Salvation Army Maj. Stanley McKinley, who had been a regular visitor while Malanik awaited his fate during the trials and appeals.

Malanik was dressed in a white shirt and brown trousers.

Capital punishment in Manitoba

Nearly two years passed from the night of the bloody shootout to Henry Malanik’s date with the hangman.

Justice in 1928, however, was much swifter. Earle Nelson, a.k.a. the Strangler, believed to be the first serial killer in North America, killed 24 women in the United States and left a trail of victims from San Francisco to Chicago. Manitoba was Nelson’s first — and last — Canadian stop.

Nearly two years passed from the night of the bloody shootout to Henry Malanik’s date with the hangman.

Justice in 1928, however, was much swifter. Earle Nelson, a.k.a. the Strangler, believed to be the first serial killer in North America, killed 24 women in the United States and left a trail of victims from San Francisco to Chicago. Manitoba was Nelson’s first — and last — Canadian stop.

He murdered Winnipegger Lola Cowan, 14, and another local woman in a 24-hour span. A massive manhunt that took the city by storm ensued. The terror lasted until the Strangler, described in the pages of the Free Press as a pathetic-looking man with a hound-dog face and vacant stare, was caught a week later in the village of Wakopa, in southwest Manitoba. He was hoping to return to the States; the border was only 10 kilometres away when he was caught. Nelson was tried and convicted in a Winnipeg courtroom and hanged in the Vaughan Street Jail only 60 days later.

Joseph Michaud, a young soldier from Quebec City stationed in Winnipeg, was the first person to be tried, convicted and executed in Manitoba in August, 1874 for brutally killing a man after a night of hard drinking in the many saloons operating at the time on the city’s burgeoning Main Street. Michaud was described as a good man who changed terribly when imbibing. Following his execution, where a large crowd was on hand and a black flag fluttered atop the jailhouse, fellow soldiers carried his coffin from the gallows to a nearby cemetery for burial.

Perhaps the most disturbing piece of Manitoba capital punishment history surrounds the controversial case of Lawrence Deacon, who was convicted in two separate trials of murdering Winnipeg taxi driver Johann Johnson. Despite a number of unsuccessful appeals by his lawyer, Harry Walsh, Ottawa rejected pleas and ignored petitions with more than 15,000 signatures and ultimately refused to commute the death sentence. The evidence against Deacon was circumstantial at best, and the lone witness for the Crown had a beef with him and continually changed her story. Longtime Free Press reporter William Morriss wrote in his memoir in 1997 that he witnessed six men hanged at Headingley Jail while covering trials and executions for the paper — and that he strongly believed Deacon was innocent of the crime. Deacon, 35, was hanged at Headingley on March 31, 1948.

In October, 1970, Thomas Shand was sentenced to hang for murdering Winnipeg Police Detective Ronald Houston, with execution set for June 10, 1971 at Headingley Jail between 1 a.m. and 6 a.m. Shand was the second person that year to receive the death sentence from a Manitoba jury. Clifford Lurvey was convicted of killing St. Boniface Police Const. Leonard Shakespeare in March 1970. Both killers’ sentences were commuted to life. Although he was spared the noose, Shand was the last man sentenced to hang in Manitoba.

A total of 52 people were executed in Manitoba between August 1874 and June 1952, when Henry Malanik became the last man executed in this province. Only one woman was executed in Manitoba; Hilda Blake was hanged at the Brandon jail Dec. 27, 1899, for shooting and killing another woman in a fit of jealous rage.

The last two people executed in Canada were Ronald Turpin, 29, and Arthur Lucas, 54, convicted for separate murders, at 12:02 a.m. on December 11, 1962, at the Don Jail in Toronto.

The last person sentenced to death in Canada was Mario Gauthier on May 14, 1976, for the murder of a prison guard in Quebec. He received a reprieve on July 14, 1976, when the House of Commons finally voted 130-124 to abolish the death penalty with the exception of some National Defence Act offences. At the time, there were 11 men on death row in Canada, all of whom had their sentences commuted to life in prison.

From 1867 to 1976, Canada sentenced 1,481 people to death and executed 710 of them.

A 2012 survey conducted by Angus Reid Public Opinion in partnership with the Toronto Star found that 63 per cent of Canadians surveyed nationwidebelieve the death penalty is sometimes appropriate, with 61 per cent believing capital punishment is warranted for murder.

— Willy Williamson

His executioner — believed to have been Camille Branchaud, who was on the Quebec government payroll as a hangman — was reportedly wearing a colourful Hawaiian shirt and a black beret. Branchaud executed people in other areas of the country on a contract basis.

There were about 40 witnesses present.

Malanik was described as looking healthy; he had gained weight while behind bars, some observers suggested.

His weight, it turned out, was misjudged by the hangman, resulting in his jugular being severed — causing blood to spurt from his neck.

He was pronounced dead two minutes later by the provincial coroner.

Willy Williamson is a Free Press editor and a former Manitoba corrections officer.

willy@freepress.mb.ca