Fast and furry-ous Drought, late frost filling ursine orphanage beyond capacity

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/08/2021 (1676 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A few choice morsels of fruit is all it takes to lure Vinny into his new home. Grapes work wonders.

The rough-and-tumble cub was the first orphan brought to Black Bear Rescue Manitoba this spring; he’s since been joined by 26 other young bears who have lost their mother for one reason or another. Space is at a premium and this season has been one long game of musical chairs for rescue operators Judy and Roger Stearns.

“The cubs were arriving so fast and furious,” Judy says. “Sometimes we were scrambling because we were having to shift bears around to make room for everyone.”

Winnipeg Free Press reporter Eva Wasney (left) and photojournalist Mikaela MacKenzie are following the story of Vinny — the first orphaned cub brought into the care of Black Bear Rescue Manitoba in 2021— from his arrival at the Stonewall-area rehabilitation centre to his release back into the wild this fall.

This is part two of three. Find the first instalment at http://wfp.to/bearrescue

Like all new intakes, Vinny’s journey started in the nursery, where cubs feed on formula and bide their time in quarantine, before he was moved into a covered, open-air enclosure in the Bear Building — nicknamed the ‘Bob Barker Building’ after the former Price Is Right host who donated $50,000 to help the Stonewall-area rescue centre get started. Vinny has been living outside full-time since the end of June and recently graduated to a large new pen with 11 of his adoptive siblings.

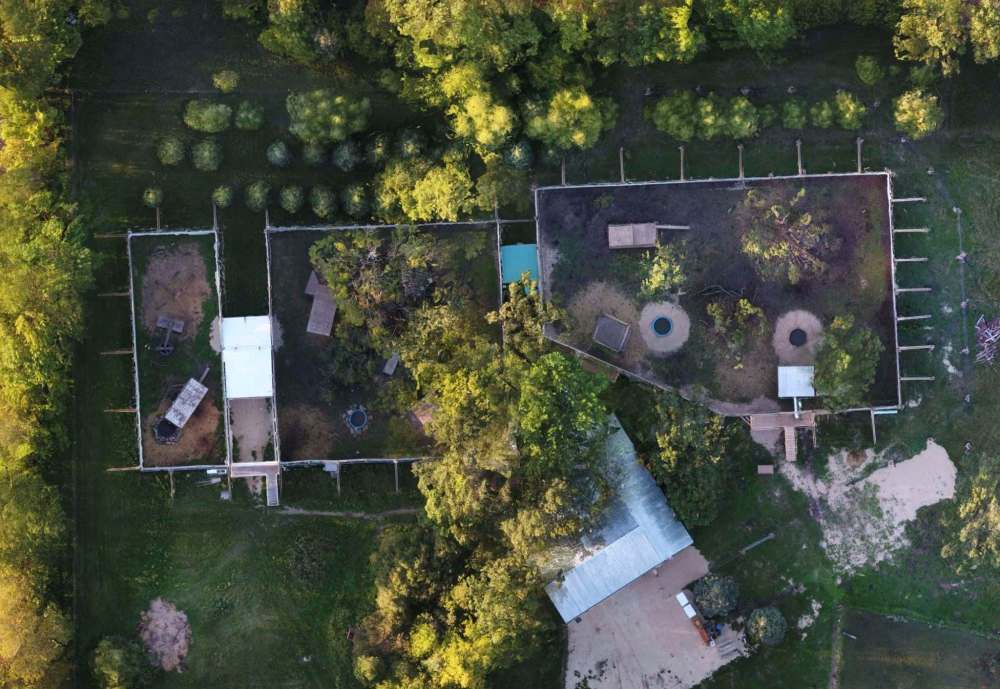

The 9,000 square-foot enclosure has high walls made of corrugated metal sheets, shelters, wooden climbing structures, trees, berry bushes and swimming pools that can be drained and filled from afar. Roger’s construction background has been a boon for the bears.

“He’s built the best facility that I’ve ever seen,” says John Beecham over the phone from his home in Idaho. He is the Stearns’ adviser and one of the world’s foremost black bear experts.

Though he’s unaware of the accolades, Vinny seems taken with the new digs. The enclosure was previously home to Teddy and Ursula, two yearlings who arrived cold and hungry last December and are now back in the bush where they belong. In preparation for the new sleuth (the name for a group of bears), the complex has been cleaned, the straw fluffed and a cache of fruit sprinkled throughout the grass.

There’s a short corridor connecting the old and new enclosure and Vinny is the first to strut through the threshold. It doesn’t take long before he’s galloping around the perimeter, splashing in the water and climbing high into the foliage. His constant wrestling partner, Wrigley, follows close behind.

“There’s really no one who is the boss of anyone else, but some of them are a little more confident,” Judy says of the cubs. “I remember saying (Vinny) was so gentle and peaceful and easy to work with. That lasted about two weeks and then he started getting more boisterous and assertive.”

Vinny is about six months old now and has yet to grow into his outsized ears. His sleek black coat shines in the sunlight and he weighs an estimated 65 pounds — more than 10 times what he weighed upon arrival. By all measures, he’s thriving.

● ● ●

The cubs are growing and so is the rescue.

For the last month, the Stearns — along with a team of volunteers and donated material — have been busy building a fourth outdoor enclosure on their 10-acre property.

“It was not planned and neither was that one,” Judy says, nodding at one of the other enclosures, which was erected last year when the centre was caring for 19 cubs — at the time, a record high.

“We built that one in like three weekends,” adds Roger. “We’re a little slower on this one.”

The pace is understandable when temperature is taken into consideration. The heat has been unrelenting and Manitoba just capped off its driest July on record, with little reprieve in the forecast. The conditions aren’t ideal — for people or wildlife.

The province has seen an uptick in interactions between humans and black bears in recent years. In 2020, Manitoba Conservation recorded over 2,100 bear sightings and encounters with people or property — an increase of more than 800 reports compared to 2018. This year is on pace to surpass those numbers.

“At the end of June there was already over 1,000 (interactions),” says Janine Wilmot, a human-wildlife conflict biologist with the province. “Most interactions get recorded during the month of August, and we haven’t even started that yet.”

Drought conditions and a late frost in some parts of the province are likely causes.

“Those two factors combined can impact the amount of food available, particularly of fruit,” Wilmot says. “People are seeing them more as they’re wandering further afield trying to find food sources and in some cases, water sources.”

Black bears are very much “motivated by their stomach, but led by their nose,” according to Wilmot. Forests are their natural habitat, but a keen sense of smell combined with the allure of garbage and foodstuffs can draw them into towns, campsites, farms and backyards. Less food in the wilderness can be deadly — and not only due to risk of starvation.

Nuisance bears, those who aren’t afraid to venture into settlements in pursuit of food, are dealt with by conservation officers. First timers will be relocated, while repeat offenders are “dispatched” or euthanized. Last year, 151 black bears were killed by provincial staff and 35 were reportedly killed by members of the public to protect property. In 2018, those numbers were 75 and 29, respectively.

● ● ●

Humans are the key to reducing bear encounters, but, perhaps unsurprisingly, humans can be harder to manage than wild animals.

Michael Campbell, a University of Manitoba professor who studies the dynamics of nature-based tourism, has been monitoring the effectiveness of the government’s Bear Smart education program on and off since 2004. In the early days of the campaign, he was surprised to hear from cottagers who knew bird feeders and compost piles, for example, could attract bears to their property, but were unwilling to remove the attractants from their yards.

How to help black bears during a drought

Bears are also feeling the heat, but even well-meaning human interactions with wildlife can do more harm than good. The following are guidelines from the province provided to Black Bear Rescue Manitoba:

Attractants can be anything that draws a bear into an area – typically a potential food source such as human food, garbage, bird feeders or fruit trees – but could also include a water source or potential shelter.

Bears are also feeling the heat, but even well-meaning human interactions with wildlife can do more harm than good. The following are guidelines from the province provided to Black Bear Rescue Manitoba:

Attractants can be anything that draws a bear into an area – typically a potential food source such as human food, garbage, bird feeders or fruit trees – but could also include a water source or potential shelter.

Water can be an attractant for wildlife, particularly in a drought situation, so it is prohibited to leave out water in areas frequented by black bears. Providing water would increase risks to human safety and could potentially concentrate animals at the water source and provide increased opportunity for disease transfer.

Secure any attractants in your yard or campsite to ensure black bears don’t get food rewards from human-based food sources. The public can help to remind their neighbours and newcomers to bear country about the importance of this. Food-conditioning increases risks for people, property and bears.

Do not pick berries. Leave the berries in the bush for the bears.

Support organizations that work towards protecting wildlife habitat to ensure long-term availability of habitat for wildlife.

“I think they just enjoyed seeing the birds on their property more than they worried about the bears,” Campbell says, adding that Victoria Beach now has a bylaw requiring the removal of bird feeders during certain times of the year as a result of his survey.

While those attitudes likely persist, cottagers these days are generally more aware of and willing to take steps to avoid conflicts with bears. The Bear Smart program has helped raise awareness, but Campbell says more explicit imagery could be even more effective.

“Sometimes there’s (a picture of) a bear near a tent, sometimes there will be human food around, but you never see the image of what happens to the bear afterwards,” he says. “There’s a whole number of reasons for why that is and it’s obviously a jarring image to see a dead bear.”

Beyond posters and pamphlets, the social norms surrounding how humans behave around wildlife needs to change, says Campbell — especially with more inexperienced campers and hikers exploring the outdoors amid the pandemic.

Habituation happens when a bear loses its natural fear of people; food conditioning happens when a bear starts associating people with food, either because they’ve been fed in the past or they’ve discovered the delights of an unattended cooler.

“Negative interactions between humans and bears are extremely rare, but if bears become conditioned to human food… that can lead to all kinds of negative interactions,” Campbell says. “When there is any kind of physical confrontation between a bear and a human that might have resulted from food conditioning, that bear will ultimately die from that.”

Despite thousands of annual encounters and an estimated population of between 25,000 and 35,000 animals, only three people have died from black bear attacks in Manitoba.

Bears would rather avoid humans altogether, but a changing climate could make that impossible. In the Prairies, droughts and extreme weather events are expected to intensify as the climate crisis progresses.

Ursus americanus is nothing if not adaptable, but conflict with humans and bear mortality will only increase as natural food sources and habitats are depleted.

“As the human population grows we’re going to see fewer and fewer bears,” says bear biologist John Beecham. “There’s going to be an increasing number of bears killed in defence of neighbourhoods… and as more people expand into bear habitats, you’re going to see a decline in the number of bears.

“In our lifetime, maybe that (decline) won’t be noticeable, but over time it will.”

● ● ●

Female bears roaming widely in search of food could explain why there are so many cubs at Black Bear Rescue Manitoba this year.

“This would be speculation,” says Janine Wilmot with the province. “But with most wildlife species, if they are moving about their habitat more, they’re more likely to be crossing roads… so there’s an increased risk of vehicle collision.”

Several cubs were indeed taken into the rescue after their mothers were hit by cars, but Beecham suspects the influx has more to do with reality coming to light.

“I think those orphaned cubs were out there all along,” he says. “But the (wildlife) agency’s policy was to not pick them up, not rescue them; just leave them to let nature take its course.”

A Manitoba Conservation study bears this out. Looking at the reproductive tracts of hunter-killed female bears, researchers estimated that — even though it’s illegal to kill a mother bear with cubs — 41 cubs, on average, were orphaned each year during the spring bear hunt between 1996 and 2000. At the time, that represented less than two per cent of the estimated number of cubs that died annually from natural causes.

Prior to the Stearns’ efforts, orphaned black bear cubs in Manitoba were either euthanized or (occasionally) placed in zoos. Beecham has been involved in the rescue from the beginning. A former research biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, he has been raising and releasing black bears since 1972, when he couldn’t bring himself to destroy an orphaned cub on the job.

“I raised it in my backyard,” he says. “I did everything you can possibly imagine that we tell people not to do in this day and age, and the darn thing still survived.”

Beecham has refined his process and is now a consultant for dozens of bear rescue facilities around the world. In Manitoba, he designed the rescue’s protocols of care and helped Judy and Roger convince provincial officials that black bear rehabilitation was worthwhile.

“There was a real reluctance on the part of the government to try this,” he says. “There’s a general philosophy in many wildlife agencies that they are there to manage populations, not individuals.”

However, attitudes about black bear rescue operations appear to be shifting among wildlife officials — even if only to score public relation points.

“If you were to let the public know that you’re shooting two-month-old cubs in the head and throwing them in the bushes rather than rescuing them, I think you’d have a black eye,” he says. “They also recognize, and I do as well, that this is largely a welfare issue.”

In other words, rehabilitating 27 cubs won’t cause a population boom locally, but it will reduce undue suffering.

● ● ●

Bears raised properly in captivity have a very good chance of survival upon release, “at least as good a chance as wild cubs,” Beecham says.

Properly, for Judy and Roger, means cutting off contact, as much as possible when the bears move outside to avoid habituation.

It’s just before 8 p.m. on a smoky day in early July and the couple is leisurely preparing for their evening rounds. Roger has only been home from work for an hour and he’s leaning back in a chair sipping on a soda while Judy mixes ground dog kibble into bowls of formula. The pablum is for the newer bears getting acclimatized in the nursery — one solo black cub and two “blondies,” as Judy calls them. Despite their name, black bears can be a range of colours, from brown, to blonde, to cinnamon and even white.

She sets down the bowls, but the cubs don’t approach. They’re likely put off by the sound of unfamiliar voices and the occasional click of a camera shutter.

“This is actually very good because we want them not afraid of the humans that they know and afraid of everyone else,” Judy says.

“Just wait, they’ll go for the produce right away,” Roger adds, foreshadowing the next leg of the tour.

They leave the wee cubs and walk over to the Bear Building, which has recently been adorned with a mural by Winnipeg artist and noted bear lover Kal Barteski. Inside, there’s a meal prep area and a large TV screen connected to cameras in the outdoor enclosures. Judy does a headcount — tough with bears running in and out of frame — and Roger checks the feeding logs. They head back out the door, each carrying a bucket filled to the brim with fruits and vegetables.

Most of the rescue’s produce is donated by nearby grocery stores and they often have to turn down offers from well-meaning folks wanting to drop off meat or fish for the bears. While the animals are technically omnivores, they mostly live off grass, berries and bugs in the wild.

“It’s gotta be something really easy to catch if they’re going to eat meat,” Judy says.

“They’ll get the odd baby deer because fawns will hide in the grass and not move,” Roger says. “But it’s mostly males who do that.”

Standing atop a wooden viewing platform, the couple starts tossing produce over the side of an enclosure. A shower of strawberries, carrots, lettuce, bananas and oranges rains down and the cubs come running. As the fall release approaches, the caretakers will stay out of view as much as possible — ducking down to deliver fruit rations and dumping kibble down a special chute.

“It’s gotta be something really easy to catch if they’re going to eat meat.” – Judy Stearns

Cleaning is also on the chore list tonight. Judy enters one of the pens through three sets of locked doors and starts picking up droppings with a pair of tongs. There’s eight cubs inside and she gives them a wide berth, but none seems keen to approach. A cub on the climbing structure is huffing and clacking his teeth — an indication he’s not enthused about a human in his space.

Judy and Roger don’t usually do feeding rounds together. There’s usually a volunteer on hand to help out in the evenings, but even that isn’t without labour.

“There’s a lot of training with volunteers because things change between their visits,” Roger says.

● ● ●

Winnipeg radio host Ace Burpee has been a fixture at the rescue for the last year. He wakes up at 4 a.m. to host his morning show and heads to Stonewall most afternoons to help with whatever needs doing. When the pandemic cleared his schedule he started filling his time with nature documentaries, which, in turn, inspired him to take action.

“I’m an enthusiast of wild animals… and bears are so fascinating,” Burpee says. “I’m used to being super mega busy and I needed a purpose that wasn’t job-related.”

His favourite part of the work is seeing the bears blossom in care. “Some of their stays here start so terribly because they’re so shaken and so scared,” he says. “You see them get some of that joy back and get to be actual bears.”

Volunteering five days a week seems like a lot, but Burpee is one of only five people who help out regularly with bear care. The team is kept intentionally small to limit human contact, which leaves the bulk of the work for Judy and Roger.

“They have the right temperament,” Burpee says of the rescue founders. “I’ll put in what’s required, but it’s a different level when everything revolves around (the bears). You have to put personal stuff to the side and it’s a massive commitment.”

There may be few people on the ground, but there are thousands rooting for the rescue from afar. As with any cute animal content on the internet, Black Bear Rescue Manitoba has amassed a legion of dedicated fans on social media.

If she could, Judy would spend her whole day posting videos, photos and educational information about bears to Facebook and Instagram. But because there aren’t enough hours in the day, she often finds herself falling behind on updates.

“I feel bad about that,” she says. “I love going on there and sharing it with people because I feel like we’re so privileged to be able to be doing this.”

Social media is also a necessary way to drum up donations for the registered charity. It costs $2,000 to raise a cub through one season and another $2,000 to purchase the radio collars required for their release. Like most bear rescues in Canada, they don’t receive any funding from the government.

“Oh yeah, we’re always out-of-pocket every year.” Roger Stearns.

“We’ve never yet had enough money donated to cover things completely,” Judy says of the last three seasons.

“Oh yeah, we’re always out-of-pocket every year,” Roger adds.

Their savings are going to dog kibble and they’re unbelievably busy, but they’re happy. You can hear it in their voices when they talk about the bears and you can see it in the smiles that cross their faces while they’re throwing fruit over a fence to dozens of cubs with a second lease on life.

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @evawasney

Eva Wasney is an award-winning journalist who approaches every story with curiosity and care.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, August 9, 2021 12:38 PM CDT: Adds share image