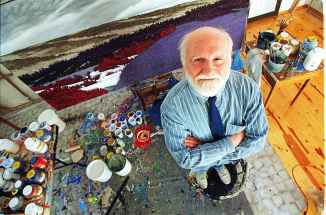

Pure imagination Panoramas or portraits, Winnipeg artist’s vast body of work was rich with metaphor

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/11/2022 (1213 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

David Loch found himself staring at the work of a genius when he first encountered an Ivan Eyre painting in 1969.

The artwork was hanging at a River Heights home, and that moment would lead the future art dealer, who founded Loch Gallery in St. Boniface in 1972, to a lifelong friendship with the Winnipeg artist, who died Nov. 5 at age 87.

“That painting did something to me because I’d never seen anything like it in my life and that painting was the thing that started everything with Ivan Eyre and what I thought of Ivan,” he says.

“I think he’s the greatest painter that this country has ever produced, or at least one of the greatest.”

WAYNE GLOWACKI / FREE PRESs FILES Ivan Eyre donated his bronze sculpture Plains Call to the garden in front of the Assiniboine Park Pavilion. The building’s

third-floor gallery is named for the late artist.

Eyre, who was born in Tullymet, Sask., in 1935, earned a bachelor of fine arts from the University of Manitoba’s School of Art in 1957. He would became a professor there in 1959 and taught until his retirement in 1993; he received an honorary doctorate of laws from the university in 2008.

He continued to draw and paint during his U of M tenure, creating hundreds of works; Loch wasn’t the only one who was fascinated by Eyre’s art. He had more than 300 solo and group exhibitions around the world, including at the National Gallery of Canada, as well as in Paris, London and Frankfurt.

He was elected a member of the Royal Canadian Academy in 1974 and was awarded the Queen’s Silver Jubliee medal in 1977. He was a member of the Order of Manitoba and the Order of Canada.

One of Eyre’s paintings hangs at Canada’s embassy in Washington, D.C.

Eyre’s depiction of nature, especially trees, bushes and shrubs, is unique. His autumn forests in paintings such as High Ground, Field Light and Red Rough reveal pointed, detailed branches rather than billows of red and yellow leaves.

These landscapes often resemble Prairie scenes but don’t waste your time scouring the countryside searching for the exact spot that Eyre transformed into art.

His works emerged from his thoughts.

”Imagination is my guide. I follow it and lead it into a world largely built on my drawings. It may be in response to a real-time visual phenomenon found in my travels, or to the close-up intrigue of a busy table in the studio or kitchen,” Eyre is quoted as saying in a Loch Gallery release. “Inspiration takes an unimpeded excursion through a mix of overlapping memories and images.”

SUPPLIED Ivan Eyre looks up at Lady Love, one of his contributions to the Sculpture Garden at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Ontario.

Loch calls Eyre’s method “pure genius.”

“There was Ivan the extraordinary person, there was Ivan the man, Ivan the creator,” he says. “Everything from his imagination put onto canvas, with no photographs and no real drawings made relating to the scale of what the canvases were… That’s the magical thing.”

Winnipeg has become home to much of Eyre’s art. In 1998, when the Assiniboine Park Conservancy restored the park’s Pavilion building, he donated 200 paintings, 5,000 drawings and 16 sculptures; the Pavilion’s third-floor gallery is devoted to his work and is named in his honour.

When the conservancy refurbished the Pavilion in 2016, it reopened with a new Eyre addition, Plains Call, a five-metre bronze sculpture that marked a different side to his artistic career.

“(The museum was built) so it could be a showcase for people coming from different parts of the world to look at what greatness is in a Canadian artist,” Loch says.

A crane installed two more of Eyre’s giant sculptures, Icon North and Bird Wrap, in front of the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 2018, where they stand sentinel above the automobile traffic on Memorial Boulevard.

It was the culmination of several Eyre exhibitions at the WAG during his career. The gallery hosted his first solo exhibition in 1964 — Ferdinand Eckhardt, the director at the time, also recognized Eyre’s genius, Loch says — and a retrospective, Figure Ground, in 2005, which included self-portraits, sometimes shrouded in paper, in addition to Eyre’s landscapes.

Another Eyre donation, this time nine more large bronzes to the Ontario-based McMichael Canadian Art Collection, are the centrepieces of Ivan Eyre Sculpture Garden in Kleinburg, Ont., a Toronto suburb.

Loch wants an Eyre sculpture garden in Assiniboine Park, too — to go along with the Leo Mol Sculpture Garden that was built in 1992 — as a tribute to Eyre, a friend who opened his eyes to art more than 50 years ago.

“You show me another genius in Canadian art that can match Ivan Eyre,” he says. “You won’t find one.”

Eyre was predeceased by his wife, Brenda Eyre, to whom he was married for 52 years. He is survived by his sons, Keven and Tyrone.

Alan.Small@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @AlanDSmall

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.