Survivor fought, died for his captors

Elijah Dickson, taken from family and forced to attend Brandon Indian Residential School, died fighting at Passchendaele

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/09/2022 (1254 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

More than 4,000 Indigenous men served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the First World War; more than 300 were killed and many hundred more wounded in body, mind and spirit. Their stories have been largely ignored, slighted or forgotten by history.

One of the men was Elijah Dickson, who served with the 8th Canadian Battalion (90th Winnipeg Rifles) from May 1917 until his death on Nov. 10, 1917 during the Battle of Passchendaele.

Dickson was born in 1890 at Oxford House (Bunibonibee Cree Nation) on the banks of the Hayes River, 950 kilometres north of Winnipeg. He was taken from his parents, community and heritage at a young age and held as a virtual captive in the Methodist Church’s Brandon Indian Residential School.

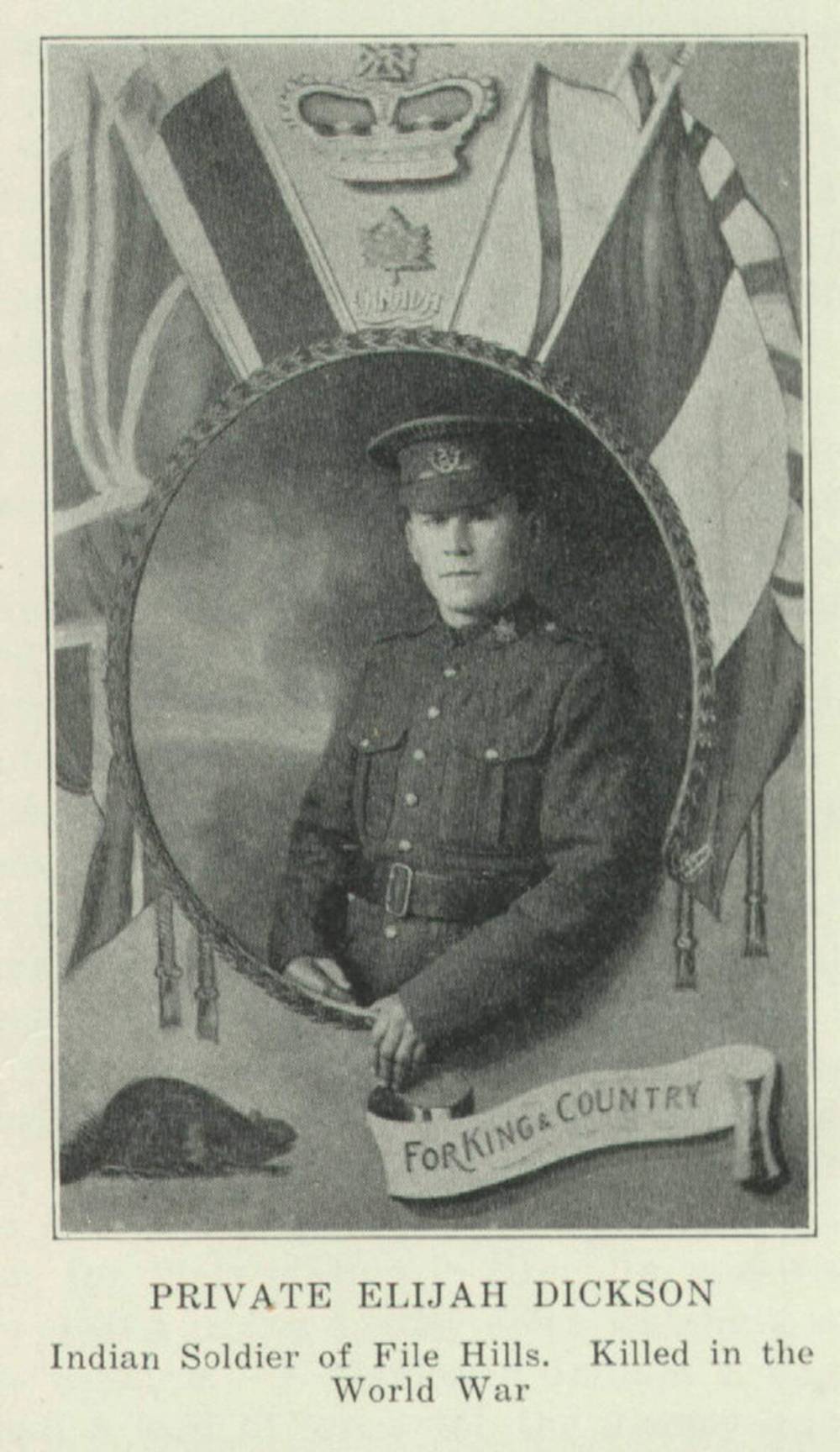

Private Elijah Dickson

The 125 students received daily religious instruction, basic reading and writing and did farm or kitchen chores. The boys learned farming, carpentry and other practical skills while the girls were instructed in cooking, sewing and other domestic activities.

He was freed from the school after his 16th birthday and settled in Saltcoats, Sask., 250 kilometres west of Brandon. He never saw his parents or home again.

In 1914, Dickson married 19-year-old Christina Bettern in a service at the Brandon Residential School. Bettern was originally from York Factory and had attended the school with Dickson. The couple moved to the File Hills Colony, an experimental farm community on the Peepeepkesis Reserve, near the town of Balcarres, Sask. In late 1915 or early 1916, their daughter Mildred was born.

The File Hills Colony band performed patriotic music in recruitment drives across southern Saskatchewan and supported loyalty to the British Empire. Every member of the band eventually enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Dickson signed up in Winnipeg on April 7, 1916 with the 203rd Battalion, which was sponsored by the Methodist Church.

In keeping with Methodist temperance principles, the 203rd was a “Hard and Dry” battalion and their recruitment poster claimed it would be “Dry from Winnipeg to Berlin.”

Dickson was two inches shorter than the average enlistee, at only 5-3 (and 3/4 inches) tall and a slight 130 pounds. The 203rd trained with other new battalions at Camp Hughes near the farming town of Carberry.

Some of his new comrades were Indigenous soldiers from northern Manitoba who later served with him in the 8th Canadian Battalion: Saint James Whiskey, from Cross Lake, was killed in August 1917; Happy Jack Ross, also from Cross Lake, was wounded at Passchendaele in November 1917; Alexander Saunders, from Norway House, was reported killed in August 1917 but was found alive and survived the war; John Swanson, from Norway House, was wounded in August 1917 and declared “medically unfit for further service.”

On May 8, 1917, Dickson and 144 other men were “taken on strength” with the 8th Battalion in France. The battalion desperately needed new men, as it had taken more than 500 casualties during the April 1917 battles on Vimy Ridge.

The battalion was in reserve in the early summer, so it was an easy start for the new recruits. However, in early August they began preparations for the attack on the German stronghold of Hill 70 near the city of Lens.

On Aug. 8, Dickson, along with 10 others from the battalion, immortalized himself by scrawling his name on the wall of a cave near the town of Hersin, France, while sheltering from a rainstorm. This was no lucky talisman, as all the men were killed or wounded within the next three months.

The Battle of Hill 70 began on Aug. 15, and it was Dickson’s first true experience of trench warfare. The 8th moved up into the line on Aug. 14 and its 720 men prepared for the planned assault. The battalion’s first objective was taken; however, it faced heavy machine-gun fire and was shelled by its own artillery. By the time the battalion was relieved, it had suffered 450 casualties. The Battle of Hill 70 and Lens continued until Aug. 25 and cost the Canadian Corps some 10,000 casualties, with almost 2,000 killed.

After the battle, in his only known surviving letter home, Dickson wrote, “I am quite well and enjoying the French weather but wishing I was home instead of here. However, I hope to get that chance yet. Most of my Indian pals are either in Blighty or Killed. Two of us Indian boys are left, four of them have paid the price for this freedom we are fighting for….”

In late October 1917, the Canadian divisions were transferred to the Ypres sector in Belgium to take part in the Battle of Passchendaele. On Nov. 8-9, Dickson’s battalion moved up to the front lines, where it was heavily shelled. The 8th Battalion War Diary reported that “25% of all ranks were buried in the viscous mud by shell fire during the 24 hours.”

On Nov. 10, the battalion attacked under a driving rainstorm and was slaughtered. The war diary reported 138 men were killed and 500 more wounded or missing. The survivors, the diary stated, were in such a weakened state that many died of exhaustion or drowned in water-filled shell holes and that the dead could not be carried out of the battlefield for burial.

Dickson was one of the men killed on Nov. 10. His Circumstance of Death Card indicates he was killed by a machine gun bullet and died “almost instantly.” He and 82 other men killed during the assault have no known graves and are memorialized on the Canadian panels at Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ieper (Ypres) Belgium.

After his death, Christina moved to Winnipeg and, in 1922, married Albert Harrington, who worked for the Municipality of West Kildonan, where the family lived. They had two children and many grandchildren. She died in Winnipeg in 1960.

Dickson’s daughter Mildred married Syd Chappell, who also grew up in West Kildonan. At some point, they moved to Victoria. They had three children who still live in the province. Mildred died in Victoria on Oct. 9, 1995. Dickson’s grandchildren did not know of him, his story or their Indigenous heritage until contacted in 2020.

The names and stories of Indigenous soldiers who died while serving in the 8th Canadian Battalion in the First World War and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles in the Second World War are memorialized in the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum.

— Ian Stewart is author of Seeing It Through: Manitoba’s Soldiers 1914-1919