Reframing rot as high art Wrought’s timelapse photography, original music find the beauty in mould, decay, ooze and desiccation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/06/2022 (1358 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Nathan Enns was driving around east of the city, on the prowl for roadkill to give to his friends.

A Rotten Screening

Wrought

West End Cultural Centre

• Doors at 6 p.m., screening at 6:30 p.m. on June 27 and 28, with Wrought Fest following the first night screening

• Free, but register at eventbrite.ca

• Proof of vaccination is required

He spotted a few small rodents, and what looked like the remains of a deer carcass, and gave them a call. The roadside detritus wasn’t an unsolicited gift: Anna Sigrithur and Joel Penner asked for it.

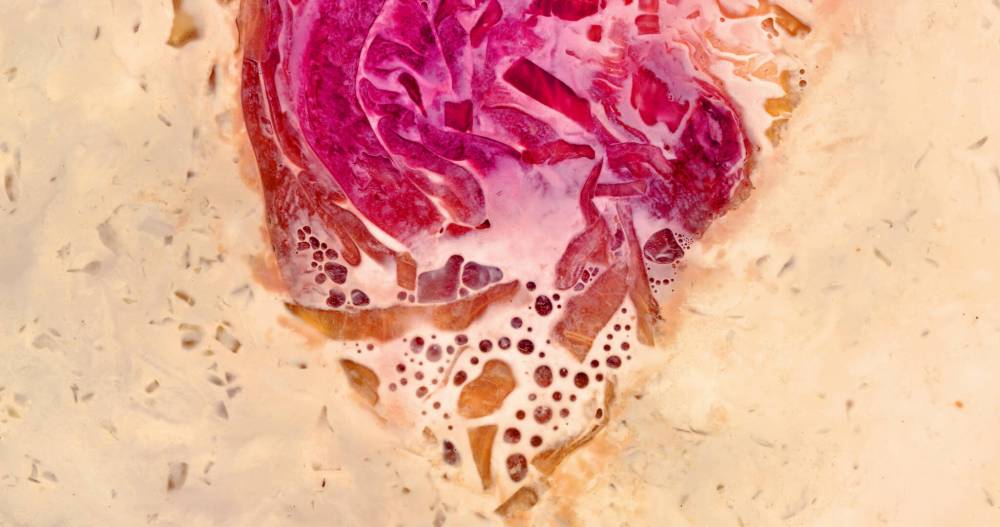

They make movies, and for their latest short film project, they needed an array of natural, organic props: watermelons, berries, fish, oranges, cabbage, corn, leaves, sourdough, kiwi, dead birds — the usual. Whatever was dead, the filmmakers wanted to watch get deader, and whatever was still fresh, they wanted to watch dress itself up in a feather boa of fuzzy mould: they wanted to watch everything turn to mush.

But rotting takes time, something at a premium in a short film, so Penner, whose previous work includes capturing flowers wilting (“I love watching them decay,” he says) sped up the clock: using time-lapse photography, he documented processes most people would rather avoid seeing – desiccation, shrivelling and rot.

The resulting work, Wrought, is a film filled with beautiful imagery and sharp writing. In 22 minutes, it will convince you to look differently at the parts of life generally deemed disgusting. As worms wriggle around in a pile of old vegetables, or as white mould creeps its way across discarded fruit, you might question whether you’re watching something revolting – you might be watching something beautiful.

“Disgust is the most common reaction elicited by rot or decay,” says Sigrithur, who has a background in food studies. “It’s our position in this film and more universally that rot is not necessarily or only a negative thing.

“We’re all so fixated on this idea of preventing decay and the desecration of the body that we forget this beautiful oneness,” she says. “We come from nothing and we return to it.”

● ● ●

Penner and Sigrithur became friends because, as Penner says, “we both enjoyed gross and nasty things.” Penner could be found photographing literal garbage, and Sigrithur could be scouring the city for urban edible plants.

On a Berlin subway a few years ago, they decided to make a film together, and eventually decided that rot was the way to go: Penner took some initial footage of cabbage in 2015 which lit a fire in him. “But it was really the watermelons that set things off for me,” he said. To watch the pink flesh bubble and burble over a span of days was hypnotic.

Soon, the self-taught Penner went all in on the time-lapse photography, and Sigrithur got to work writing a script tying the imagery together. They thought it might take a year or two. In the end, 22 minutes took six.

Between Penner’s photography and animation and Sigrithur’s narration and writing — which took 80 drafts to perfect — the film feels and looks like an exploration of a vast universe. It’s like you’re looking out the window of a space shuttle and seeing constellations of mould blooming like supernovae.

A mesmerizing segment shows beetles and worms composting organic matter in what looks like a second but really was several days. In another, a fish loses its flesh right down to its bones, and then evaporates into nothingness. Each frame reveals the intricacies of decomposition, as well as its glory: green fuzz turns blue, and the white wicks of mould interlace like braided hair. In a world of disorder, the process of rot restores balance.

How do you compose music for decomposition? That was the conundrum for Randolph Peters, who tried through sound to mimic the images on screen: the bubbles, the colours, the death, the life, the mystery.

A professor of music composition at York University, Peters showed the footage to his class as a project and experiment in score composing. “Some students got grossed out,” he said. One student, Joshua Maikawa, might have been disgusted, but was clearly inspired, and got his own work included in Peters’s score.

“In the end, it’s a beautiful film,” says Peters, who lives in Winnipeg. “It looks at times like you’re watching a whole universe exploding in front of you in slow motion.” The microbial participants in rot “are almost sentient.”

Beautiful or disgusting, Winnipeg will get to decide for itself. After strong showings at the American International Wildlife Film Festival — where it won the New Visions Award — and in Turin, Italy, the film will have its Canadian debut at the West End Cultural Centre next week. (In July it will play the Gimli International Film Festival).

On June 27 and 28, Wrought will play the WECC. On the first night, Penner and Sigrithur will also host host what they call Wrought Fest to explore the appealing side of decay. Cheese from artisanal makers Loaf and Honey, sourdough goods from Gato Bakeshop, funghi from River City Mushrooms, and cider from Next Friend — crafted from fallen crabapples and other backyard salvaged fruits — will be the focus of the fest. Indigenous gardening methods will also be taught by a local elder.

But the film is the main event: to watch the rotting process on the big screen will evoke emotion and thought, Sigrithur says.

At the end of the film, each item depicted in its decomposition is thanked with credits, as are the people who provided the organic matter. Nathan Enns works in the film industry on the props side: this is the first time he has been credited as an animal donor.

No animals were harmed in the filmmaking process, and Penner and Sigrithur both say it was very important to them to respect natural processes and capture them as they truly happen.

“I think this film will get audiences thinking about how everything isn’t just ugly or beautiful,” Sigrithur says. “It’s often both.”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.