Out-of-sight oversight Regulatory body’s secretive approach to investigating Manitoba doctors accused of misconduct protects physicians at the expense of patient safety, critics argue

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/06/2022 (1269 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The woman walked out of the doctor’s office that day feeling violated.

It was 2011, she was 19 and she had an appointment for her first full physical exam with the physician she’d been seeing since she was a baby. But she knew he wasn’t supposed to touch her that way.

“I asked him to stop,” she said. “He was just very reassuring, very calm, (saying) ‘This is what a physical is.’ … It was very sick.”

Afterward, she told her family and friends what happened. Many believed her but some minimized her concerns and discouraged her from going to the police, she said. They said it would be a difficult process for her, considering it would be her word against a prominent physician’s.

“I felt like I had no power,” she said.

Doctor timeline:

1990: Arcel Bissonnette begins practising medicine in Manitoba.

2001: The alleged assaults begin, according to court documents.

Sometime on or prior to Jan. 8, 2019: At least one person makes a complaint to the College of Physicians and Surgeons Manitoba regarding “concerns” about Bissonnette.

1990: Arcel Bissonnette begins practising medicine in Manitoba.

2001: The alleged assaults begin, according to court documents.

Sometime on or prior to Jan. 8, 2019: At least one person makes a complaint to the College of Physicians and Surgeons Manitoba regarding “concerns” about Bissonnette.

Jan. 8, 2019: In response to the complaint, CPSM has Bissonnette sign a “voluntary undertaking” accepting the following condition on his licence: “A female attendant must be present during a breast or pelvic examination of a female patient.” He is required to post a notice about this condition in his practice. Still, for three patients, the alleged sexual abuse continues, according to court documents.

Nov. 5, 2020: Ste. Anne police arrest Bissonnette, charging him with six counts of sexual assault. The alleged offences involve female patients and took place between 2004 and 2017 while he was working at the Ste-Anne Hospital and the Seine River Medical Centre. Police did not say how long Bissonnette was under investigation but referred to the probe as lengthy.

Nov. 6, 2020: Bissonnette’s practitioner profile is removed from the college’s website. A court condition bars him from practising medicine and the college also asks him to sign another “voluntary undertaking” stating he won’t practise medicine. When physicians cease practising, the college wipes their online profiles.

Oct. 21, 2021: Police charge Bissonnette with 16 more counts of sexual assault. Sainte-Anne Police Chief Marc Robichaud said more patients came forward with allegations of abuse after his 2020 arrest. According to court documents, the alleged offences spanned 19 years, taking place between 2001 and 2020.

Resources for survivors of sexual violence:

Klinic Community Health’s 24-hour sexual assault crisis line can be reached at 204-786-8631. The SANE program at Health Sciences Centre can be reached by 204-787-2071 and asking for the SANE on-call nurse. More information at klinic.mb.ca and hsc.mb.ca/emergency.

So she stayed silent for nearly 10 years. But after learning through news reports in November 2020 that her doctor — Arcel Bissonnette — was charged with six counts of sexual assault involving patients, she knew she needed to come forward. By October 2021, she was one of at least 16 more women who had reported allegations of sexual assault to police. Bissonnette, who is in his early 60s, is now charged with 22 counts of sexual assault for alleged incidents spanning nearly 20 years in both Ste. Anne, a community 45 kms east of Winnipeg where he practised, and Lorette, located just southeast of Winnipeg, according to court documents.

None of the allegations have been proven in court and he is presumed innocent. Bissonnette’s lawyer did not respond to requests for comment. Bissonnette was released on bail and his medical licence has been suspended.

The woman, who can’t be named due to a publication ban, was stunned to recently learn someone had raised concerns about him with the physician watchdog, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba (CPSM), nearly two years before he was arrested. The college responded to the complaint by placing gender-based conditions on Bissonnette’s licence in January 2019. (She stopped going to Bissonnette after the alleged sexual abuse a decade ago.)

If she’d known someone else had raised concerns, she would have gone to police sooner, she said.

Instead, the regulatory body kept those concerns secret, allowing Bissonnette to continue practising for another year and 10 months. According to a Free Press review of court documents, three of the eventual 22 charges are dated to alleged incidents during that time, despite a condition placed on him by CPSM requiring him to have a female chaperone present while conducting breast and pelvic examinations on female patients.

The secrecy surrounding this case and others is the subject of a Free Press investigation into how the CPSM handles allegations of physician misconduct. Critics argue the college’s approach places the protection of physicians ahead of patients, leaving patients potentially exposed to everything from inappropriate behaviour to criminal offences. One advocate for survivors of sexual violence said the college has “failed” patients.

CPSM registrar Dr. Anna Ziomek declined to be interviewed for this story. The CPSM would only respond to questions by email.

In a submitted statement, Ziomek said disciplinary action has been imposed only in a small number of cases and that there are other ways to ensure patient safety.

“CPSM ensures qualification requirements for licensure are met, sets high standards of competence and practice, and monitors the quality of the practice of registrants, all of which contribute to patient safety,” she said in the statement. “We are continuously reviewing our processes to identify where improvements for quality care and patient safety can be made, including our Standards of Practice.”

“We are continuously reviewing our processes to identify where improvements for quality care and patient safety can be made, including our Standards of Practice.”– Dr. Anna Ziomek, CPSM registrar

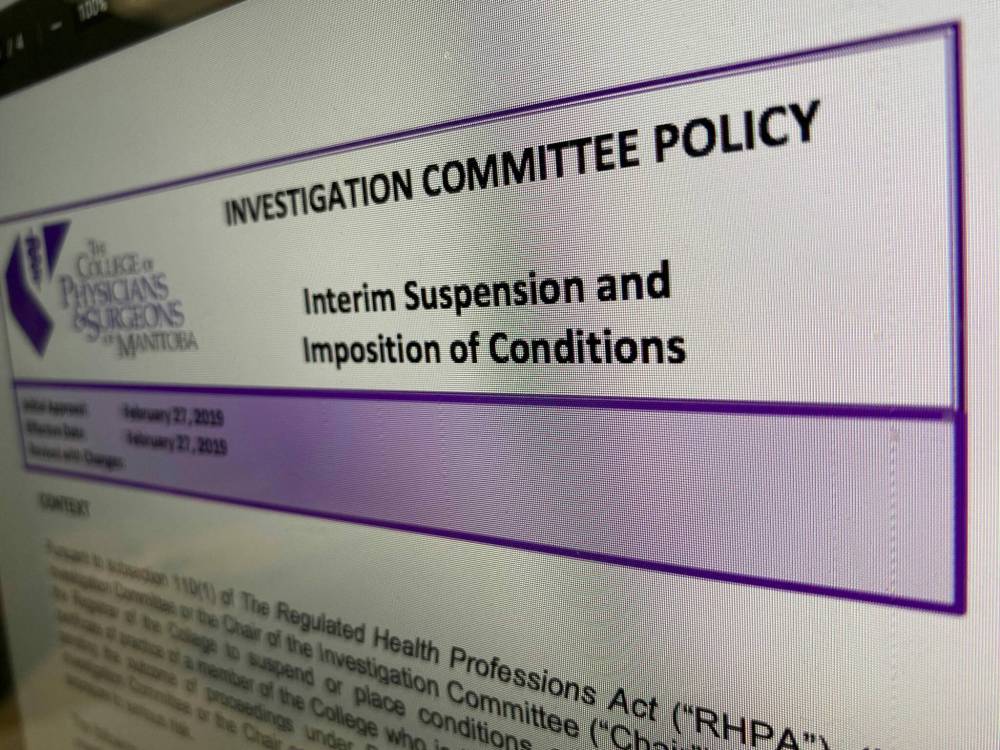

Critics say it’s imperative the college updates its practices and that the province overhauls legislation governing the college — the Regulated Health Professions Act (RHPA), which covers all of Manitoba’s regulated health professions — to guarantee transparency and better patient protection.

Currently, much of how the college handles physician misconduct happens behind closed doors. What is known is that when the college receives a complaint, it takes one of four steps: resolves them through “facilitated communication;” refers them to the college’s complaints committee; refers them to the investigation committee; or dismisses them. Even if the complaint is possibly criminal in nature, the college typically only reports matters to police if they involve minors.

The college’s official mandate speaks mostly to its role in regulating the profession and ensuring its members are meeting standards set out by law. However, the college also said its role is to protect the public and “promote the safe and ethical delivery of quality medical care by physicians in Manitoba.”

One critic argues the very foundation of the college’s structure — self-regulation, or doctors overseeing doctors — commits the college to prioritizing physicians and their interests over patients.

“The system is fundamentally broken,” said Paul Harte, a Toronto-based medical malpractice lawyer.

Self-regulating professions are inherently flawed, he said, in that there is often little external oversight and those in charge are elected by their peers, leading to a greater incentive to maintain the status quo, rather than pushing for transparency and stricter discipline. The government, or an independent oversight body, would be best positioned to take over regulatory duties, Harte said.

In her statement, Ziomek said the CPSM is “bound to operate within the framework of the RHPA.”

“We exercise the provisions that allow for transparency to their full extent. We recognize some improvements can be made, but overhauling the RHPA extends beyond CPSM’s medical regulatory authority and can only be amended by the Legislative Assembly.”

Health Minister Audrey Gordon declined an interview request. An unnamed government spokesperson said it would be “inappropriate” for her to “comment on a specific case.”

Harte, meanwhile, said the focus should be on victims of abusive physicians and what could be done to stop them. The Bissonnette case specifically raises questions about how CPSM operates, he said.

“The public is left to simply trust without verification that the system is working,” Harte said. “And then when you have situations like Bissonnette come up, the public is left wondering, ‘Well, what happened?’”

Harte believes the college should make all complaints against physicians public. Such a move would pull back the curtain on what they are accused of and how the college is handling the complaints. For example, even if a physician regularly receives similar complaints that are eventually dismissed, making that information public could at the very least suggest to patients they should be on the alert, and should compel the college to examine underlying issues, such as poor communication with patients, Harte said.

Either way, Bissonnette’s patients deserved to know more, he said.

A second victim, who alleges Bissonnette sexually assaulted her for nearly 15 years, agrees, saying patients should have been warned he was under investigation.

“I don’t understand the oversight,” she said through tears.

Sonam Khangura, a frontline worker with Vancouver Rape Relief, said the college’s current practices serve to protect physicians, leaving patients vulnerable to harm.

“The college of physicians had a duty to protect women and they failed,” Khangura said.

Khangura said the college should have immediately contacted patients and informed them about why Bissonnette was required to have a condition on his licence. Then, the college should have done a “quick and thorough” investigation to assess the matter and resolve it appropriately, she said.

Christy Dzikowicz, executive director of the Toba Centre, which works with survivors of child abuse in Manitoba, agrees the CPSM needs to be more transparent.

“If we ever want to prevent these things from happening, we have to take misconduct allegations seriously,” Dzikowicz said. “If they felt it was serious enough that (Bissonnette) had to have a female chaperone with him, then that sounds serious enough to share with the clients that he serves.”

Lorian Hardcastle, an associate professor with the University of Calgary’s faculty of law, said patients deserve to know if serious complaints have been lodged against their physician. Firstly, it promotes trust with patients, and secondly, it can encourage potential complainants to come forward.

“It’s important for those people who … they’re not sure if they want to report, they’re not sure if they’re misinterpreting the situation — for those people to be able to go and look and, if there’s been something in the past, that might be the thing they need to embolden them to report,” she said.

That doesn’t happen in Manitoba.

CPSM spokesperson Wendy Elias-Gagnon said in accordance with the RHPA, the college makes public final disciplinary decisions after an investigation has concluded, but not details of allegations prior to the decision being released. And those investigations can take longer than a year.

“There is currently no process in place for notifying a physician’s patients of an investigation (and) we cannot alert other potential complainants due to the privacy requirements of the RHPA,” Elias-Gagnon said in an email.

The CPSM also refuses to reveal details about the initial complaint it received against Bissonnette, including the nature of the complaint, if multiple complainants came forward and when the complainant(s) reported, citing “confidentiality reasons” under the RHPA. The college will only say it received at least one complaint relating to “concerns,” which led to Bissonnette signing a “voluntary undertaking” restricting his licence in January 2019.

The condition required Bissonnette to have a female attendant present during breast or pelvic examinations of female patients. He was required to post signage informing patients of as much in his practice and the college was also required to note the condition on his online profile. The CPSM said it was not aware he breached any conditions of the restrictions on his licence, nor has it “received allegations of misconduct occurring” while the restriction was in effect.

The college’s policies state such conditions are meant to protect patients, pending the outcome of an investigation.

But one of the victims said patients deserve to know about serious allegations against physicians so they can make informed decisions about their health care. Instead, she was kept in the dark.

“I’m just super f—–g angry,” she said.

The other victim who alleges she was sexually assaulted in 2011 said she feels guilty, thinking she could have stopped him sooner.

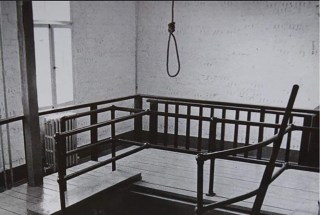

She said she “absolutely” would have reported what allegedly happened to her, had she known others were allegedly enduring what she went through — had the CPSM made the initial complaint public. She’s outraged the CPSM never suspended his licence, something that the college’s policies state is an interim option.

In response, the college said courts in Canada have decided “regulators such as CPSM should not impose interim suspension based on allegations alone.” It’s unclear what court cases the CPSM is referring to.

That’s not good enough for the victim.

“Why would you let a predator practise?” she asked.

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter with the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.