Vaccine success, suspicion on First Nations Uptake on Manitoba reserves above 80 per cent overall, but some communities battling social media misinformation, hesitancy based on historic health mistreatment of Indigenous people

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/10/2021 (1516 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As the date for Long Plain First Nation to host its annual powwow approached, community leaders were carefully weighing whether to move forward with the long-awaited gathering scheduled for a three-day stretch in mid-September.

In a typical year, the celebration would draw upwards of 1,000 people from across Western Canada and the United States to the community south of Portage la Prairie.

However, in Saskatchewan and Alberta — where some communities had successfully held large powwow events through July — new COVID-19 infections were on the rise after provincial governments had lifted the majority of public-health restrictions.

Meanwhile in Manitoba, chief public health officer Dr. Brent Roussin had announced tightened restrictions that capped outdoor gathering sizes at 500 people, with exceptions for events following protocols approved by health officials.

But one of the most pressing concerns for Long Plain was the on-reserve immunization rate: less than 20 per cent of eligible residents had been fully vaccinated by the first week of September.

Ten days before the powwow was set to begin, the First Nation cancelled the celebration for the second consecutive year.

“At the end of the day, a lot of people were quite disappointed, but I think a lot of people appreciated the decision that had to be made and, for the most part, to accept that decision,” Chief Dennis Meeches told the Free Press.

“It was a very tough decision to make. With everything that’s going on with the pandemic, there’s too many unknowns. We did have a fairly low vaccination rate and, to some degree, we still do.”

According to Long Plain’s own statistics, about 34 per cent of the on-reserve population had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of late last week. An estimated 2,500 people live in the community, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada says.

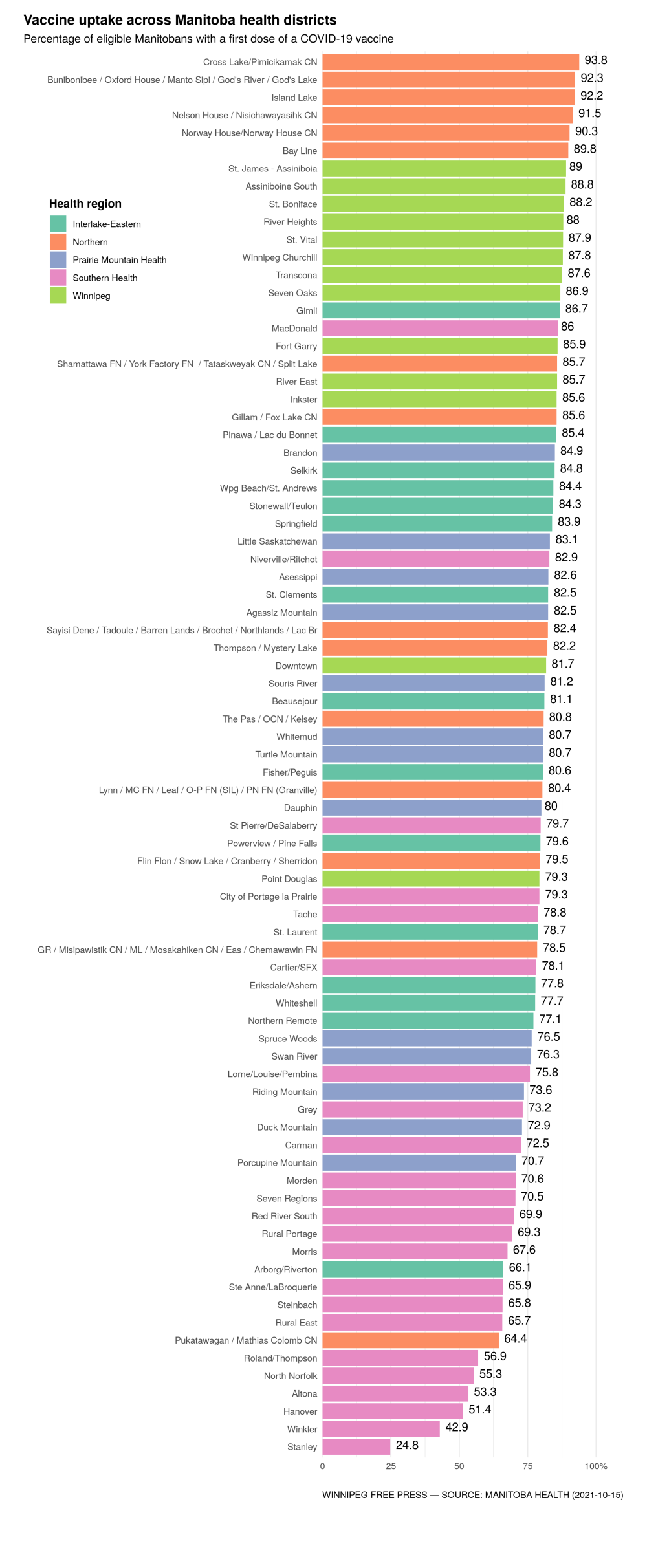

On average, COVID-19 vaccine uptake on reserves across Manitoba is high, with more than 82 per cent of residents fully immunized, data from the Manitoba First Nations Pandemic Response Coordination Team indicates.

However, the patterns of low vaccine uptake seen throughout the province are also being reflected in some First Nations communities.

In the Southern Health-Sante Sud health region — an expansive district that covers 27,000 square kilometres — 66.2 per cent of the eligible population has chosen to be vaccinated.

Meeches said misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines and distrust of the government and the health-care system are two of the most common sentiments among unvaccinated community members.

“We have to somehow convince them that this would be the right thing to do to protect themselves, their children, their family and their community,” he said.

“But again, there’s a lot of mistrust out there, and I think maybe that mistrust can be attributed to the mistreatment that Indigenous people have faced generation after generation. So a lot of people have a tough time reconciling all of that and (are) saying, ‘Why should we trust the government now?’”

Introducing incentive programs, including a lottery, has been considered in a bid to drive up vaccination levels, Meeches said.

Peguis First Nation, a community of about 3,600 people in the Interlake with a vaccination rate of 62.1 per cent, did that earlier this week, offering members who are fully vaccinated a chance to win one of 50 draws for $1,000.

“But again, there’s a lot of mistrust out there, and I think maybe that mistrust can be attributed to the mistreatment that Indigenous people have faced generation after generation.” – Chief Dennis Meeches

However, there are concerns such programs could cause further skepticism on Long Plain, Meeches said.

“People have questions about that. Is that ethical?” he said. “Those are really tough, legitimate questions that people have.”

The band has sought legal advice on vaccine mandates for the community, he said. But for the time being, provincial orders requiring proof of immunization for many indoor public places, recreation and gatherings seem to be motivating more people to roll up their sleeves.

“I’d hate to be the chief that mandates vaccines on Long Plain. I’d rather try to avoid that,” Meeches said. “I think we need to encourage people.

“We need to let them know that the vaccines are safe, but we can give all the information about this through our medical-health professionals, our doctors; we can provide all of that and some people will still say no.”

At Sagkeeng First Nation, a community of more than 3,600 people on the shore of the Winnipeg River, Chief Derrick Henderson is also grappling with the challenge of boosting a stalled immunization rate.

About 50 per cent of eligible people living on the reserve were fully vaccinated as of Wednesday, Henderson said.

“You’d always love to have it higher,” he said. “There are people that are not going to get it, it doesn’t matter what I do. I just wish we could figure out a way to increase it.

“It’s a difficult task when you get all of the social media that’s happening regarding vaccination, the anti-vaxxers. It just instils (doubt) in our people, too.”

Henderson said he regularly promotes immunization in the community and distributes relevant information along with the weekly vaccine clinic held every Wednesday.

A recent clinic at the local school was successful in getting more doses into arms, Henderson said, adding some parents took their kids to get a shot.

“I think we’re at a good point. It’s just a matter of us being persistent.” – Chief Derrick Henderson

He expects any meaningful increase in uptake will flow from conversations in the community, often between health-care providers and patients, rather than external campaigns or mandates.

“There is so much mistrust right now, it doesn’t matter who it is,” he said. “I’m using my health department as much as possible because we have a lot of people there that people know and trust, right?

“I think we’re at a good point. It’s just a matter of us being persistent.”

Dr. Marcia Anderson, public health lead with the Manitoba First Nations Pandemic Response Coordination Team, said vaccine promotion needs to continue on- and off-reserve, especially as the fourth wave begins to impact Manitoba communities.

“We all understand how urgent it is arguably, perhaps, even a bit more for First Nations, where the coverage is lower,” she said.

There are approximately 27,500 eligible First Nations people living on reserve who still require one or both doses to be fully vaccinated; about 15,000 of them are under the age of 30.

The on-reserve population also tends to skew younger, Anderson said, meaning a greater proportion of people living in First Nations communities who aren’t eligible to get the vaccine yet can be infected and spread the virus.

“We need to have even more of those who are eligible fully vaccinated in order to try to interrupt those transmission chains,” she said.

She encouraged people who are reaching out to others who are not vaccinated to share reliable sources of information and listen respectfully to their reasons for not being immunized yet, especially people who have “experienced trauma in the health-care system or other government institutions.”

“That’s a really hard barrier to cross,” she said.

And in First Nations that have been successful in their vaccination efforts, influential community leaders — chiefs and council members, health directors and school staffs — have often been at the forefront, taking the lead in promoting and planning campaigns, Anderson said.

“Seeing the effects that this virus has on an individual, a family member or community member, that impact resonated within the community and the region and helped emphasize the importance of protecting yourself, your family and community.” – Executive director of Four Arrows Regional Health Authority Alex McDougall

Four such communities are in Island Lake, roughly 500 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg, where vaccination coverage is currently hovering at about 90 per cent for Garden Hill, Red Sucker Lake, St. Theresa Point and Wasagamack.

Alex McDougall is the executive director of Four Arrows Regional Health Authority, which provides health services for about 15,000 people in the region.

He said the high immunization rates can be attributed to strong leadership from chief and council, but also an aggressive campaign that included targeted outreach by health-care professionals for people who were slow to be vaccinated.

However, one of the biggest drivers of participation was previous experience with H1N1, SARS and government responses to outbreaks in the past, McDougall said.

“In 2009, in the H1N1 outbreak, when our communities reached out for support from the governments, one of the ways they decided was a priority in providing that support was sending body bags,” he said. “That was totally opposite of what the communities were looking for in assistance.”

After a very difficult second COVID-19 wave in which schools were shuttered and two of the four communities required assistance from the military to manage outbreaks, McDougall said the already tight-knit isolated community was highly motivated.

“Seeing the effects that this virus has on an individual, a family member or community member, that impact resonated within the community and the region and helped emphasize the importance of protecting yourself, your family and community,” he said.

danielle.dasilva@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.