From sportscaster to journalism instructor to bank robber From behind bars, Steve Vogelsang opens up about his life's downward spiral into crime

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/02/2020 (2216 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

DRUMHELLER, Alta. — As the man left the bank that night, clutching $2,400 cash he’d prised from the teller at the barrel of a glue gun concealed in a bag, he walked, but did not run. He never ran after robbing a bank. That’s what police would be looking for, he figured, a fleeing suspect desperate to get away.

By then, he was confident in this approach. It was Oct. 19, 2017, and over the last four months he’d already robbed four other banks without getting caught, striking three in Regina and one in Saskatoon before walking into this Royal Bank in Medicine Hat, Alta., just as the sun set around 8 p.m.

It was the same routine he had fine-tuned since an awkward, futile first attempt that July: there was the fake gun in a bag. The baggy clothes disguising snappier-looking duds. The terse note, slid to the teller: “This is a robbery. Put $2,500 on the counter. Be fast and quiet.”

Except this time, something would be different. As he walked to his truck, parked on a side where there were no security cameras, he spotted a woman pulling up to the bank. The two made eye contact. “It’s almost like she suspects me of something,” he thought.

In retrospect, this is where his crime spree began to go wrong. He had planned to leave Medicine Hat that night, hightail it to Lethbridge, get out of Dodge; but his truck busted a wheel bearing. So he decided to stay and strike another bank the next morning while his truck was in the shop, but the repairs took all day.

Two years later, this is the moment he will say he got “lazy and stupid.” If he had been smart, he would have left town as soon as the truck was roadworthy. But his hotel suite was comfortable — it had a jacuzzi — and he hadn’t gotten caught yet, so he opted to grab dinner and head out the next morning.

When he did finally leave Medicine Hat, it would be as a prisoner.

That night, armed with the witness description of the truck, police cased the parking lots of local hotels. They spied his vehicle, and pulled his driver’s licence photo. It matched an image taken from the bank’s security camera of the suspect, clad in a red flannel shirt buttoned up tight, faded cap pulled low over his eyes.

That is the image that will sweep across social media just days later, after he is arrested. The first headlines were utilitarian: “Winnipeg Man, Stephen Vogelsang, Charged With Robbing Banks.” The details were sparse, brief accountings of the allegations lifted from the antiseptic wording of a police press release.

In Winnipeg, a newspaper journalist was scrolling through Twitter when the story caught her eye. That’s weird, she thought: her old Red River College journalism instructor must have a relative of the same name. It had to be some other Steve Vogelsang, not her once-favourite teacher, not the former popular sportscaster of local TV.

Then she peered more closely at the man in the photo, and her breath caught in her throat. He looked heavier than what she remembered, and there was something different in the eyes. The eyes she recalled were always lit with some sharp and yet-to-be-uttered joke; the eyes in the photo were focused and cold.

But there was also something distinctly familiar about the set of the jaw, the sharp angle of the nose. The more she stared at the image, the clearer things became, and yet the more confusing. There was only one logical conclusion, but that was the one that made the least sense of all.

She was not alone. Across Canada, stunned journalists shared the news with each other.

I am gobsmacked. Used to know Steve well: Former CTV broadcaster Steve Vogelsang accused of robbing 2 Alberta bankshttps://t.co/7qSCapPQ7l pic.twitter.com/xdUNGmBndE

— Diana Swain (@swaindiana) October 23, 2017

For the next two years, as news trickled out about his charges, his subsequent guilty pleas and his sentencings to five years in prison for the four Saskatchewan robberies and 18 months for the two in Alberta, many wrestled with how to resolve their image of a popular mentor with that of a six-time bank robber.

The answers never seemed to come, no matter how hard they tried. So one day in late 2019, a writer reached out to Vogelsang through a mutual friend. A few weeks later, her phone started to buzz, and when she picked up there was no mistaking the voice: husky but firm with the confidence of a man accustomed to holding an audience.

“Melissa, it’s Steve Vogelsang,” the man on the other end said, cheerfully. “How are you?”

There isn’t much to see in the visiting room at Drumheller Institution, a medium-security facility nestled in the hills about 130 km northeast of Calgary. There are featureless walls clad in grey fabric, stained with old spills; a rickety vending machine populated by a handful of chocolate bars; a jumble of children’s toys on the floor.

“You’re perfectly safe in here,” a friendly guard says, ushering a visitor inside. “There are cameras everywhere.”

As the visitor waits, she mulls over what she came here to find. It’s hard to know where to begin. There are so many things to understand, and so many questions. But in a way, they all lead to the same place: what the hell happened?

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Vogelsang says, propping his elbows on one of the round glass tables spaced throughout the room.

“People are expecting an answer that makes all of this make sense, that makes everything fall into place. In the end it doesn’t make sense, because I can’t explain it myself. Every day, I go, ‘what was I thinking?’ Even when I try to take in the factors that contributed to my low point in my life, I still think, ‘so? What was I thinking?’”

He is 56 years old now, and time has changed him. His close-cropped hair has gone grey. On his forearms he sports two prison tattoos, given to him by a guy named Smiley. On the left, a Joan Baez lyric he read shortly after his arrest: “Action is the antidote to despair.” On his right, a mantra: “If you only have a dollar, get your shoes shined.”

Vogelsang holds his arms out, explaining the “prison ingenuity” behind jerry-rigged tattoo machines.

“I figured, hey, I’m going to prison, I may as well have the full prison experience,” he says.

That experience isn’t what he feared it would be. It’s not like on American movies and TV, he says: the other inmates on his range, a section of about 20 solo cells, are friendly. The guys try hard to get along. He hasn’t seen anything like the tough posturing or threats that fiction had taught him to expect.

He is not like most of the other inmates at Drumheller. Most of them never really had a chance. They came from shattered lives, from families battered by poverty and intergenerational trauma. Most of them battle an addiction that spurred their crimes, but find relatively little mental health treatment in prison.

Vogelsang does not have an addiction. He’s heard some people back in Winnipeg have wondered that: was it drugs that drove him to rob banks? Was it gambling? Did he owe debts to scary people? None of the above, he says. That would be too obvious, too easy an explanation for how he came so undone.

What he does have is notoriety, in a way others here do not. Three journalists have come here to interview him in under a month; in an email chain accidentally sent to the Free Press, one Correctional Service of Canada worker joked to another, “I wonder which one of Mr. Vogelsang’s former students or colleagues will be next?”

“People are expecting an answer that makes all of this make sense, that makes everything fall into place. In the end, it doesn’t make sense, because I can’t explain it myself. Every day, I go, ‘what was I thinking?’ Even when I try to take in the factors that contributed to my low point in my life, I still think, ‘so? What was I thinking?’” – Stephen Vogelsang

The inmates have picked up on this, too. “Prison guys love to gossip,” Vogelsang says, and his crimes made a big splash on the news, so the other men on the range knew all about him when he arrived. At night, when they have a few hours of free time, there is a “fairly constant stream” of guys dropping by his cell to chat.

He helps them out sometimes. He offers them advice. He helps to write their release plans and resumes. It’s not entirely altruistic: favours are valuable currency in prison, and it’s useful to be popular. Some of the younger men seem to look up to him, he says, as someone who once had a successful life “on the outside.”

“I’m a believer in this: that we don’t like people, we like how people make us feel,” he says. “One of the reasons they’re in here is because nobody ever made them feel good. Nobody ever made them feel valued or special or smart or validated in any way… so when I talk to them on a one-to-one level, it’s really validating.”

This sounds familiar, his visitor notes. It’s almost like the relationships he once had with some RRC students.

“In a way,” he agrees. “Students who would punch somebody out for you, if somebody were to give you any kind of grief. And I don’t get any kind of grief, from anybody.”

His days are uniformly uninteresting. In the morning, he gets up early to work on his memoir, typing it out a computer so old it still takes 3.5-inch floppy discs. In the afternoons, there is a mandatory program to help offenders understand their crimes; each night, he watches Jeopardy on his cell TV.

He’s had a lot of time to think, in prison. To think about how and why he took his life on such a sharp and criminal turn. To think about all the people he hurt, from his family to the tight-knit group of old childhood buddies who still stand by him. To think about all the people who looked up to him, who he disappointed.

“All my relationships are positive,” he says. “I don’t have anybody to blame for putting me in here. I’m the one to blame for that. That’s all on me. It isn’t because I had an unhappy home life or anything like that. It’s because of things I did. Nobody led me astray. But the same can’t be said for a lot of people in here.”

Once he had made a name for himself almost on force of personality alone. He served on the Winnipeg Humane Society board and emceed dozens of well-heeled charity dinners. He was one of the toasts of the town, friends in high places, a big fish in Winnipeg’s infamously small pond.

Then, one bad decision after another, he dismantled it all. That’s always been the strangest part about the story, the one those who know him struggled to figure out. There’s no obvious juncture where his life fell apart, no tragedy that befell him, no act of God. In fact, nothing terrible happened that he didn’t do himself.

On June 3, 2011 — six years, five months and three days before he walked into a Royal Bank in Regina, kicking off his robbery spree — Vogelsang stepped out of a white SUV limousine that had pulled up on King Street outside the King’s Head Pub, then a popular hangout for reporters and RRC students.

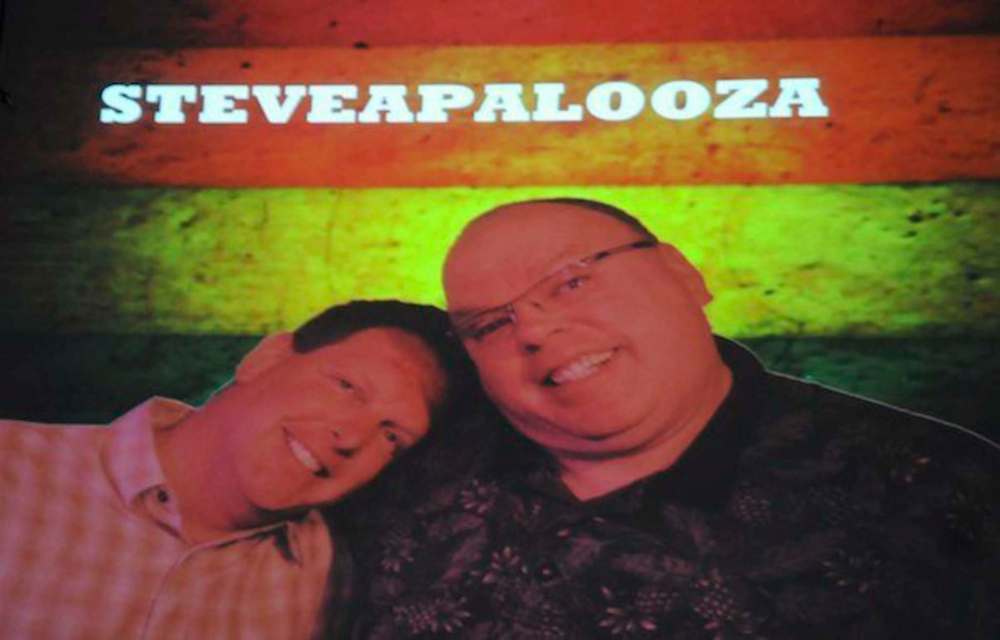

Inside, a few hundred people were waiting to greet him, mostly students and former colleagues. His siblings had come to Winnipeg for the occasion, along with his teenage nephews. As they mingled, clips of Vogelsang’s CTV highlights beamed on a hanging screen, and a live band kicked up a rollicking jam.

The event, called Steveapalooza, was Vogelsang’s going-away party from Winnipeg and it was entirely his idea. If that seems like sheer hubris, he is, to this day, unapologetic. Folks can say it shows his ego, he says, to which he replies by paraphrasing baseball Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean: it ain’t bragging if you can do it.

“Everybody wishes they had the balls to name a party after themselves, hire a band, and have people line up to get into it,” he says. “People are lying if they say ‘no, I wouldn’t want that.’ Bulls–t. I wanted to say goodbye to everyone, I wanted a big-ass party, and what’s the party for? It’s for me, so might as well name it after me.”

That type of showmanship came naturally to him. He’d been like that as a youth growing up in Saskatoon, where he cultivated a big and boisterous group of friends. He was “always well known,” he says: he performed comic skits and emceed high school variety nights. He felt destined to become famous.

After an aborted attempt at becoming a teacher, television seemed the most promising outlet for those talents. He arrived at a good time: it was the last hurrah of the golden age of local TV. Viewership was robust, the perks were rich, and newsrooms hadn’t yet felt the economic quakes that would soon knock them off their feet.

A few years after graduating from Ryerson College, he got his big break in Winnipeg when he was offered a job at CKY (now CTV News Winnipeg). Vogelsang, at the time a 27-year-old with a couple of years experience at a tiny Prince Albert station, was an off-the-board hire, but then-CKY sports director Peter Young was impressed.

“He was a different cat,” Young says. “He didn’t fit the norm. Back in those days it was jock journalism. I think about guys like myself and Randy Turner and Paul Edmonds and Scott Oake, the guys I was around a lot… Even if it was just playing on a softball team, everybody was a jock to some degree.

“Steve had none of that,” he continues. “He was literary. He was a brainiac. He spoke a language that was different from everybody else, and that’s what endeared him to everybody… He had the best sense of humour, and with that and his command of the English language, I couldn’t help but hire him.”

On air, Vogelsang’s style was brash, playful and intensely personality-driven. It made for a polarizing figure, but by his own account he didn’t care if viewers were offended. An unabashed “homer,” he gleefully referred to opposing teams as “filthy.” He taped bits about his mediocre golf game and challenged Blue Bomber players at bowling.

“He wasn’t afraid to go outside the box, and just be goofy, and be himself,” says longtime sports journalist Shawn Churchill, who first met Vogelsang in 1991 during a student job placement and credits him with helping land his first full-time job. “I think people were drawn to that. That’s what I knew him as, and still to this day.”

When Young left the station, Vogelsang was promoted to sports director; by the late 1990s, his name held enough cachet that the old Winnipeg Stadium had a sponsored section for children with disabilities called The Vogel-Zone and Uptown Magazine readers voted him Sexiest Winnipegger.

But by 2000, Vogelsang was chafing. When the NHL Jets left the city in 1996, he says, the fun went out of the sports gig; he’d always seen himself as more of a personality than a sports journalist, and the thrill of that was ebbing. He then moved up to become the local CTV news director, but didn’t enjoy that work either.

There was a new opportunity that intrigued him. In 2002, Red River College was preparing to move its Creative Communications program to its new Princess Street campus. The program was also eager to expand its broadcast training, which until then had been limited, and Vogelsang jumped at the chance to build it.

That job, he found out, fit him like a glove. As an instructor, he was tough but charismatic, with an abrasive energy that won the admiration of many students. His celebrity status also conferred a sort of legitimacy: when now-CBC Vancouver reporter Megan Batchelor started CreComm in 2005, her father was “starstruck,” she says with a laugh.

There was no question Vogelsang enjoyed that reputation. He played to this rapt young audience, entertaining them with anecdotes from his travels or his years in TV. Yet he was not an idle recipient: he could be generous with his time, especially to those students in whom he saw his own stubborn drive reflected.

“There’s no way I would be doing the job I am today if it wasn’t for Steve,” says TSN Radio host and 2011 CreComm grad Darrin Bauming. “He was always on my side. He always believed in me. When everybody else was like, ‘you’ve got the wrong attitude to work in media,’ he always stuck with me. I’d be doing something else if not for Steve.”

But after nine years, Vogelsang found himself again angling for a change. He feared becoming a relic, an instructor out of touch with the industry. In March 2011, he announced he was leaving Winnipeg to follow his and his now ex-wife’s longtime dream of living in the picturesque mountain town of Nelson, B.C.

The news of his departure trended on local Twitter, as students and friends expressed their dismay.

“I should clarify, I’m not leaving, I’m moving,” Vogelsang tweeted in response. “‘Leaving’ implies I won’t be there for you and that will never happen. I’ll help from Nelson.”

I should clarify I’m not leaving, I’m moving. "Leaving" implies I won’t be there for you and that will never happen. I’ll help from Nelson.

— Steve Vogelsang (@SVogelsangsays) March 11, 2011

The first time Vogelsang tried to rob a bank, he chickened out. It was July 7, 2017, and he’d parked in front of the Royal Bank on 7th Avenue North in Regina just before it closed. The bank was busier than he expected; as he watched people flow in and out, he decided, with a sense of relief, to abort the mission.

It was only a temporary reprieve. He returned to the bank the next morning, and this time put his plan into action. By then, he’d made a firm decision that robbing banks would be the best way to escape his crushing debt, and he had always prided himself on being a man who followed through with his ambitions.

“Because I’d convinced myself that I had to do this, I didn’t want to not do it because of a lack of courage,” he says. “I should have not done this for ethical, for moral and for legal reasons. But the reason I chose to do it was because I didn’t want to not do it because my courage failed me.”

From the start, the robberies were a performance. For the first one, he’d concocted a whole narrative, posing as a man whose granddaughter had been kidnapped. He made a fake bomb, a beeping box he held under his coat with wires coming out of it. While he waited, he pictured his dog dying until his eyes misted with tears.

At the counter, he handed the teller a note that ordered her to give him $50,000. She told him she didn’t have that much. In court documents, she described how he was agitated, apologetic: that was a part of the act, he says now. She described how he told her to clear out the bank, because the bomb was going to blow.

She set out a stack of $20 bills, and told him that’s all she had. Flustered, he left without taking it.

“I thought, ‘God, I don’t want to go to prison for $400,’” he says. “At that moment all I want to do is get out of there… so I thought, ‘let’s just call the whole thing off, forget it, it’s not going to work, let’s get out of here and forget any of this ever happened.’”

This moment, according to Vogelsang and others who knew him in that time, was the culmination of a six-year spiral that began when he moved to Nelson. If that hadn’t happened, he believes now, the rest wouldn’t have either. It was Nelson that brought him face-to-face, for the first time in over two decades, with failure.

The town is beautiful; the couple owned a rental property and settled into a condo. Vogelsang’s then-wife, Laura Gellatly, had already landed a job selling radio advertising and flourished in the gig. Her vivacious personality fit right into the community; Vogelsang jokes she “could have been mayor.”

He was not so embraced. He’d assumed he would find success in Nelson, the same way he had in Winnipeg. He’d always had “unfailing self-belief,” after all. But his name held no cachet in Nelson and his cockiness rubbed many people the wrong way in a close-knit and private mountain town.

“It was a domino that knocked down a number of dominoes in a really weird and unfortunate direction. It was the first one. I peaked at Steveapalooza. That was the best point of my life. Next thing I’m in Nelson where I’m unlikeable and unemployable. That was the next phase of my life.” – Stephen Vogelsang

For the next four years, he struggled to find work and soon fell into a deep depression. He managed to scrounge a few gigs, including a short teaching stint in China and a job selling cars. Often he would go days without leaving the house, his self-esteem battered, growing increasingly more isolated and despondent.

It had never occurred to him that he might fail in Nelson. When he did, he lacked the humility to adapt to it.

“It was a domino that knocked down a number of dominoes in a really weird and unfortunate direction,” he says. “It was the first one. I peaked at Steveapalooza. That was the best point of my life. Next thing I’m in Nelson where I’m unlikeable and unemployable. That was the next phase of my life.”

In 2015, the couple moved back to Winnipeg, where his struggles continued. Vogelsang was announced as new vice-president of human resources at True North Sports and Entertainment; that job fizzled out within weeks. He snagged a series of short-term contracts teaching business administration at RRC.

I’m coming home. I’m incredibly happy to announce I am joining the executive team at True North Sports & Entertainment as the new VP of HR.

— Steve Vogelsang (@SVogelsangsays) May 9, 2014

By the summer of 2017, his life had fully unravelled. His marriage fell apart on the back of his increasingly erratic behaviour. He was broke, saddled with an expensive mortgage, and his credit cards were tapped out. He briefly thought about declaring bankruptcy, but decided he knew a way to avoid it while keeping his pride intact.

All he had to do was rob 25 banks, clear his debts and start over fresh somewhere like Vancouver Island.

“I had to do something to get money quickly that would require no violence,” he says. “As it turns out, as I’ve since learned and come to accept, it is a violent crime. I didn’t think of it as violent at the time but I wasn’t thinking of it from the standpoint of the victim, of the people on the other side of that counter.”

To most people, the jump to bank robbery sounds ludicrous. Today, Vogelsang agrees: if he’d told any one of his friends, they would have shaken him out of it. Then he could have crashed in their basement for awhile, fixed his finances, gotten back on his feet. Yet, somehow, robbing banks seemed a better plan.

“Many times, I asked myself, ‘am I in my right mind?’” he says. “And the answer came back: ‘oh yeah, this is not a bad plan, you’ll get away with it and nobody will ever know.’”

In the years since, he has come up with different theories about his thinking. At the time, he was taking medications for depression, Wellbutrin and Effexor. According to him, a psychiatrist he’s seen in prison thinks he had an “organic episode” in his brain, and was possibly suffering from altered thinking due to the medication.

He’s on different medication now, and says he feels more like himself than he had in years. But he doesn’t want to focus on that too much, lest he be seen as trying to avoid responsibility for his crimes: after all, he says, lots of folks go through bad stretches or have poor reactions to meds, and they don’t rob six banks.

There is one thing he wants to emphasize. In victim impact statements submitted during his sentencings, the tellers he robbed reported a range of trauma. One called it the most terrifying moment of their life. Once, Vogelsang didn’t consider their feelings. That’s changed, he says, thanks to a support program in prison.

“I get it that this serves me right. I deserve this, and I will live my entire life now with the realization that I have terrified some people,” he says. “But I really had convinced myself prior to these crimes that they were victimless. How I saw it was: they’re trained for this. It’s not their money. There’s no weapon involved.”

No weapon, but only he knew that. The point of a fake gun, after all, is to deliver a lethal threat.

“Had I been able to feel what I feel now, in terms of empathy, I would not have done it,” he says. “In six robberies it wasn’t until the third one where I actually saw somebody scared. Obviously that didn’t impact me profoundly enough that it stopped me.”

The hubris, the self-confidence, the sense of infallibility in his own decisions. These were the things that once made him a compelling broadcaster and a popular instructor. They are also the same things that, in the end, drove him to commit one of the strangest crime sprees in memory, and hurt a lot of people.

“This entire experience has been humbling, which really is not that harmful to me,” he says. “My critics would say, ‘well, you needed one of those,’ and I would admit to that. It has helped me grow as a person.”

When the news broke of his arrests, it sent waves of disbelief rippling across Canada. In Vancouver, Batchelor woke up to find her phone inundated with texts from her former RRC classmates; when she went to work, curious co-workers sidled up to ask if she knew the man in the photos.

Yes, she told them, he was her mentor, someone she’d turned to for advice long after she graduated from RRC in 2007. When she moved to B.C. without a job lined up, he was the one who assured her that, with her talent, she’d land on her feet. When she was assaulted on air in 2015, he’d reached out to praise her composure.

“That day was like, insane,” Batchelor says. “I woke up to so many text messages and screen caps of that image. I could not believe that it was him. My brain was like, ‘that’s not Steve. These people are all mistaken.’ One, it didn’t look like him, and it didn’t seem like him. It didn’t compute in my head at all.”

Over the years, the shock former students and colleagues felt faded into a sort of fuzzy confusion. His name is sometimes a punchline now: more than one person, when contacted for this story, started laughing in bemused disbelief when they found out why a reporter was calling.

Some cut ties, disillusioned by the disturbing revelations about the man they thought they knew. To others, the memory of who he was to them once still lingers when they think of him, and that makes space for reflection.

“I’m empathetic. Not to what he did, but to where he was in his life, because I’ve had similar struggles,” Bauming says, softly. “I think a lot of people have. Because he was such a huge influence on me and I looked up to him so much, I feel really bad for him. I was proud to be a protege of his, really proud.”

“I have no problems talking about what I’m doing and what I’ve done. I’m humbled by this, but I’m unabashed. I’m not going to be sheepish about this. I did it, everybody knows I did it. I’ve been made a fool of for doing it, and it would be worse if I walked around with my head down. Instead, I’m going to own this, and that’s easier for everybody.” – Stephen Vogelsang

Vogelsang knows the hurt is out there, and that he will likely spend his life navigating it. He is undaunted.

“I’m not defined by one four-month stretch in my life where I melted down and robbed six banks,” he says. “I’m not only a bank robber, in the same way I’m not only a teacher or I’m not only an ex-sportscaster. I have to rebuild my reputation, and I’m fully prepared to do that… but this is not the end of life for me.”

He has his first parole hearing in June, and as a first-time offender with no disciplinary issues in prison, he stands a good chance at release. If granted parole, he will move to a halfway house in Calgary. He does not plan to return to Winnipeg, or to contact former friends or colleagues who have severed ties.

Instead, he hopes to start a new career, although he’s not certain what that will be. He is planning to release the book he’s been writing, which he hopes will offer the explanation that he thinks Winnipeggers want and deserve. And he plans to become an advocate pushing for better mental health and addictions support in prison.

“I see it as an opportunity,” he says. “Very few people in my stage of life get to start a whole new life with a blank slate. I have no expectations to meet. I have no image to keep anymore. I have no pitfalls built into my life and no problems whatsoever when I get out of here… that’s a very liberating and freeing thing.”

Still, there are some things that, once done, cannot be undone. A life built on personality and reputation is not easily mended once people have begun to ask whether they knew the person at all. There will be no way to put those pieces back where they were, and there will, probably, always be questions.

He fixes his visitor with a steady gaze, not blinking, not looking away.

“I have no problems talking about what I’m doing and what I’ve done. I’m humbled by this, but I’m unabashed. I’m not going to be sheepish about this. I did it, everybody knows I did it. I’ve been made a fool of for doing it, and it would be worse if I walked around with my head down. Instead, I’m going to own this, and that’s easier for everybody.”

In the visiting room, a guard pops his head through the door, signalling that time is drawing short. Vogelsang stands and offers a handshake goodbye, and for a minute he slips back into the role of the instructor, doling out praise from on high: “good work,” he tells his visitor. Then he’s gone, and he does not look back.

Outside, the skies over Drumheller are flecked snowy white. The reporter turns down the road that leads away from the prison, and as its gates fade into the distance, she thinks of something Vogelsang tweeted once, back in 2013.

“Here’s something to consider as you enter the weekend,” he wrote. “Do not confuse notoriety with popularity.”

And while I have your attention, here’s something to consider as you enter the weekend: Do not confuse notoriety with popularity. Sv

— Steve Vogelsang (@SVogelsangsays) June 1, 2013

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, February 14, 2020 7:33 PM CST: fixes typo