Misery infects virology lab: deadly pathogens, toxic workplace Winnipeg researchers producing brilliant science — including the Ebola vaccine — but current, former staff reveal litany of problems inside walls of high-security, high-pressure federal facility

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/09/2019 (1922 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

OTTAWA — On an October 2016 afternoon, Sky Soule ran down the corridors of the National Microbiology Laboratory, screaming as senior managers chased after her.

The bacteriologist was renowned for her work preparing labs across Canada for bioterrorism threats, and working with the RCMP to secure sites such as the Vancouver Olympics.

But after 16 years of working at Canada’s highest-security lab on Arlington Street in Winnipeg’s West End, Soule’s mental health began to deteriorate. She told friends senior managers were ostracizing her.

Normally known for her style and quick wit, she had been showing up to work in T-shirts and yoga pants, at times smelling of alcohol. Two months after the breakdown, she died in a coma after stumbling down a flight of stairs at home.

The incident, along with plunging morale documented in staff surveys, prompted the director of the Public Health Agency of Canada to reach out to local unions, and fly in for an urgent meeting with executives — an almost unprecedented move for federal institutions.

The lab, known as NML, is a source of pride for its role in creating the Ebola vaccine. It’s one of the few facilities in the world accredited to handle the most deadly pathogens. It officially opened in 1999 to much fanfare, after political wrangling had it ultimately placed in Winnipeg.

Yet numerous people who work there have told the Free Press of a workplace rife with intimidation, alcohol abuse and clashes between officials in Winnipeg and Ottawa, which was partially revealed this summer in an administrative breach that has the RCMP investigating a shipment of dangerous substances to China.

“The sad thing is, they do world-class science, but internally they’re almost self-destructing, in terms of how they treat their employees,” said Todd Panas, national president of the Union of Health and Environment Workers.

“The collateral damage to get that science is pretty remarkable.”

● ● ●

SOULE joined NML in late 2000, and was tasked with preventing and assessing bacterial exposures. After the 9/11 attacks, she helped co-ordinate bioterrorism responses, from training provincial labs on how to test suspicious packages for anthrax, to deploying the lab’s mobile diagnostics truck to high-profile gatherings.

Friends describe her as someone who was always on the ball. Her Charleswood home had a full garden, trendy furniture and home-cooked food for unexpected visitors. When she found an ornate paper lamp too pricey, she figured out how to make it herself.

In 2010, Soule’s supervisor Steven Jones left the lab, prompting an organizational shuffle in which the bacterial-testing division needed a leader, and there were few candidates for the role.

The lab eventually chose a biologist who does not possess a PhD. Nine of the 11 division heads at the lab are doctorates; the other one leads a division that does not undertake research. Those in the industry said this is uncommon, though PHAC disputes this and noted that the division head’s own supervisor has a PhD.

In any case, Soule’s colleagues say both her new manager and the director took a strict approach to the rules in her division, in line with the expectations of their own superiors.

“I found them to be bullies; they were like high-school mean girls,” said Amanda Everton, who worked in Soule’s division until 2014.

PHAC would not make anyone available for an interview unless it could screen the questions.

Previously, the lab operated on loose shift schedules, so long as the work was being done. Now, Soule would arrive from lunch five minutes late and both managers would be waiting for her at the front door.

Most often they heard her (Soule) complaining about her being demeaned and belittled at work, particularly by her supervisor. She filed complaints and applied for other positions, but nothing else seemed to fit her specialized skill set.

They increased scrutiny of Soule’s work, and she chafed at being assigned tasks alongside University of Manitoba students. She was taken off training of first responders, and instead given menial tasks such as monitoring kits that were sent to provincial labs to verify their testing.

Friends and colleagues say she was dealing with personal issues, from a difficult separation with her husband with whom she had a child, to possible postpartum issues after having a second child with a new partner.

But most often they heard her complaining about her being demeaned and belittled at work, particularly by her supervisor. She filed complaints and applied for other positions, but nothing else seemed to fit her specialized skill set.

Everton worked in several divisions at the lab, and each had “fantastic scientists” — but the bacteriology section was “a train wreck.”

She left a stable government job with a pension for night nursing shifts down the street from the facility in the emergency room at Health Sciences Centre.

“I find that to be way less stressful than working at the lab,” Everton said. “I don’t regret leaving the lab.”

The incidents she recounted were raised by numerous people who either work at the lab or left to take jobs in related fields. The Free Press has agreed not to name these people, as they fear professional retaliation.

Soule’s division was also rattled by the July 2015 discovery of a tuberculosis sample that sat untouched for a year under a tool bench. The incident didn’t become public until the Free Press reported it four months ago.

Soule’s division was also rattled by the July 2015 discovery of a tuberculosis sample that sat untouched for a year under a tool bench. The incident didn’t become public until the Free Press reported it four months ago.

By the time it was discovered, the Petri dish had cracked open, although the pathogen had dried out, sparing the risk of an outbreak in Winnipeg. People working in that division felt managers weren’t punished for failing to uphold safety-inspection protocols.

Things took a turn after a spring 2016 trip to Ottawa to co-ordinate national threat responses. The visiting team from the lab went for dinner with Mounties, some of whom Soule had worked with for years. She made an off-colour joke at the dinner. Numerous colleagues recounted Soule’s manager later reprimanding her about it, in front of her entire team.

Colleagues recall Soule looked rough that summer, either acting robotically or snapping at them. A few believe she was in touch with the on-site nurse. Friends said she was on anti-depressants, and seeing a counsellor.

People in the lab said she appeared drunk on more than one occasion, in one instance spinning around an office chair, apparently mistaking the lab for her own home. One saw her carrying blue capsules used to store ethanol away from work areas, prompting suspicion she was drinking high-alcohol substances on the premises.

PHAC would not speak to specific incidents, citing employee privacy, but argues the facility has an overall healthy work culture.

“While isolated workplace problems occur and are expected within any place of work, there is no evidence that these reflect systemic workplace issues,” wrote Eric Morrissette, the head of PHAC’s media team, in an email response to a series of Free Press questions.

It’s unclear what set Soule off during her last day at work, on Oct. 21, 2016. Colleagues saw her stumbling down a hallway, swearing at the top of her lungs. Managers tried to calm her down. The on-site nurse walked her out of the building.

Two months later, Soule stumbled down a flight of stairs at home. She died in a coma on Dec. 27 at HSC.

“What happened with Sky was so unnecessary,” Everton said. “There needs to be repercussions.”

● ● ●

IN fall 2017, public servants in Ottawa presented the head of PHAC with a report that spelled out — in red text — a morale issue at the lab.

The Public Service Employee Survey is a recurring appraisal of how civil servants feel about workplace safety, culture and compensation. NML staff submitted responses that summer, which were presented in a preliminary report to Siddika Mithani, who presided over PHAC until a shuffle last February.

Of 600 NML employees, the third who fill out the survey report a better work experience than most public servants, and even their colleagues within PHAC. But parts of the lab reported a lack of confidence and trust in colleagues. Workers at the lab had told Mithani that senior managers were part of the problem, and that Soule’s death still loomed large a year later.

That’s when Mithani called the lab’s unions, asking them to help her intervene, instead of turning directly to NML managers.

Panas said that’s an extraordinary move in Ottawa’s hierarchical public service, but he says the issues at NML go beyond a typical federal workplace.

“The lab is a hot spot for us,” said Panas, who represents 10,000 public-service employees in multiple provinces, across several departments and agencies.

On Nov. 14, 2017, Mithani met with roughly 30 senior staff at NML, alongside representatives from UHEW and the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada, another union that largely represents scientists at the lab.

A handful of those who attended the meeting say they discussed a lack of trust between employees and their Winnipeg managers, as well as those same managers and their Ottawa counterparts.

PHAC declined interview requests for Scientific Director General Matthew Gilmour, who heads the facility, as well as Soule’s supervisor and the Ottawa bureaucrat who oversees NML. But in a lengthy statement, the agency said the meeting was instead about “addressing workplace issues” in general.

“We would like to be clear that this meeting was held to support open dialogue and awareness of the range of tools and supports available to managers and employees when workplace issues arise. No specific workplace issue was discussed,” wrote Morrissette.

Yet those at the meeting say one of the key issues raised was scientists being promoted into jobs that require supervising and management duties, without adequate training or interest in the administrative tasks.

Faye Kingyens, a UHEW steward for the lab, would not speak to specific incidents for this article, in line with PHAC policies. However, she said that generally, union members have complained about supervisors who don’t know how to manage.

“I don’t know how much training they get to become managers (and) having to deal with a bunch of staff and different personalities,” Kingyens said.

“There are managers with different styles of managing, and they have to learn what is acceptable and what isn’t.”

Her comments echo the findings of a 1994 auditor general report that examined research agencies across the public service. The report found few federal agencies paid much attention to how their managers supervise teams.

The audit specifically noted that few institutions train scientists with skills such as “project management, team building, effective conduct of meetings and managing poor performance.”

In 1999, the auditor general suggested agencies were grappling with how to adequately compensate people with rare skills in order to compete with universities or private-sector opportunities, and that this may drive agencies to promote scientists into management roles that have higher salaries.

PHAC insists that’s not happening at NML, and that managers are promoted based on their skill sets and are trained to supervise teams.

“Management positions require competencies that reflect the requirements of these jobs. Scientists are not promoted to these positions as a means of increasing their salaries,” Morrissette wrote.

The hallways of NML now have posters with information about mental health and a respectful workplace. Earlier this year, managers put cue cards on tables in the lab cafeteria, asking questions such as whether employees feel safe, if they’ve ever been harassed and how PHAC can improve mental-health supports.

In Ottawa, PHAC officials are especially concerned about the public’s perception of the Biosafety Level 4 laboratory — the only one in Canada —given it handles the most deadly infectious diseases, including Ebola.

“Like any organization, we are continuously evolving to respond to circumstances when they arise and to support employee wellness. In recent years, we have better tools and processes in place and will continue to change them as new needs emerge,” Morrissette wrote, noting encouraging results from last year’s public-service survey of NML.

Mithani now oversees the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, which also has staff at NML who test for animal diseases. None have told the Free Press about workplace issues that those on the PHAC side have raised.

“I firmly believe that there is no room for disrespect, harassment or other inappropriate behaviour in our places of work, or in the interactions we entertain with colleagues and stakeholders,” Mithani wrote in an email.

● ● ●

SOULE’S 2016 death still resonates with longtime employees at the lab. Many feel NML managers favour scientists who get breakthroughs, and neglect those seen as causing problems.

Even smaller issues that are commonplace in the public service have stoked conflict within NML, such as procurement.

The lab regularly buys equipment for deployments, such as protective suits and special backpacks to safeguard employees visiting Ebola-stricken areas. The sight of supplies sitting unused, while other divisions complain about ordering their own materials, led to griping among staff, who felt teams get different responses to their requests for gear.

Numerous employees have complained that their managers have arbitrarily denied their requests for training and attending conferences, despite collective agreements outlining a right to advance scientific credentials to keep in line with emerging knowledge, a charge PHAC denies.

Panas said almost every month NML employees report bullying and intimidation.

“A lot of the bullying and harassment is coming from senior management,” Panas said. “Senior management are well aware of the toxicity of that workplace.”

Meanwhile, an employee caught smoking cannabis within the building years before its legalization got a stern warning from managers but no formal sanction, fuelling claims of special treatment.

Last year, PHAC commissioned Blaine Donais, a mediator specializing in workplace conflict, to undertake a “workplace health assessment” of the division of NML that handles administrative work, which counts roughly 50 people in areas such as human resources and the shipping dock.

Panas said the move came after PHAC reneged on an agreement to conduct a joint assessment of multiple areas of the lab, a claim the agency did not refute.

“We have strong and collegial relationships with the various unions representing scientists and other employees at the NML,” Morrissette wrote, describing regular meetings and input that he said informed a more transparent hiring process.

Donais finished collecting data by March of this year. The agency received his report during the summer, but it won’t be shared with unions until he formally presents it to management, likely next month.

In March, Donais recommended PHAC have an arms-length ombudsman conduct “studious exit interviews” with those leaving the lab, to understand workplace issues. Six months later, “our plan is to make them a systematic part of our management approach,” Morrissette wrote.

The lab’s first scientific director general, Frank Plummer, said he hadn’t come across severe personnel issues during his time at the helm of NML, from its 1999 opening until 2014. But he described the workplace as ambitious staff clustered around stressful projects.

“It’s a high-pressure environment, and the people who are working there are highly trained, highly skilled and fairly temperamental sometimes,” Plummer said in an interview. “They can sometimes react in strange ways.”

Jones supervised Soule before the period in which she complained about harassment. He said the lab might be having a hard time adjusting to less activity, after facing SARS, H1N1, Ebola vaccines and high-profile projects such as the Vancouver Olympics.

“It was relentless. And incredibly productive. But I think it’s become less productive recently, but I think that’s a natural process of things evening out,” said Jones, who left the lab in 2010.

“You can’t maintain that pace forever. It just completely wears people out.”

Regardless of what’s causing the lab’s current issues, Panas said its employees need competent managers.

“Everyone is walking on eggshells in that institution,” he said. “It’s too big of a problem for one person to address or fix.”

● ● ●

NUMEROUS workers at the lab say they fear a repeat of the Soule situation. A manager at NML overseeing high-risk projects such as Ebola research was put on leave last winter after showing up smelling of alcohol and, at one point, interrupting a teleconference meeting.

The employee returned to work in May and was effectively put on library duties instead of the previous, normal work within the lab, before being put on leave a month later.

More than a year ago, one employee threatened to commit suicide at the lab, to send a message to superiors. Panas said senior managers responded quickly when they became aware of the threat, and the Free Press has confirmed the individual is now receiving help.

Morrissette acknowledged that NML can be “demanding,” by nature of working with diseases. “NML management is committed to open dialogue with employees; our highest priorities are the physical safety and mental wellness of our staff.

“Like any workplace, we encounter challenges and conflicts and individuals may struggle with personal issues,” he wrote, citing programs such as “mandatory training in Mental Health First Aid,” an ombudsman and respectful-workplace training.

Last November, 20 senior NML managers signed a new workplace wellness policy statement that focuses on “the psychological health and wellness of employees,” such as improving the lab’s work culture and fighting stigma.

Earlier this month, a week before the federal election campaign officially began, the Free Press asked Health Minister Ginette Petitpas Taylor for an interview, which her office said was not possible.

Kingyens, the union steward who hears directly from colleagues at the lab, said there’s room for improvement. “The biggest issue with the mental-health part is getting the training for lower-level management.

● ● ●

NML had a difficult relationship with Ottawa before its scientists began working in Winnipeg in 1998.

Bureaucrats had spent a decade planning a centralized research facility to lead diagnostic testing that would replace an aging lab in Ottawa. In 1987, prime minister Brian Mulroney’s government chose to have the new facility built in Winnipeg, prompting pushback from capital-region politicians.

Mulroney’s decision came a year after its controversial call on CF-18 military aircraft maintenance, which saw a Quebec firm outbid a Winnipeg company, despite the latter being more cost-effective.

The bulk of NML staff work out of the Arlington Street building, which is formally called the Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health. Some NML employees also work nearby at the J.C. Wilt Infectious Disease Research Centre on Logan Avenue.

Many at the two Winnipeg sites and at PHAC’s Ottawa headquarters agree that employees from the two cities often clash. They describe Ottawa’s public-service culture as heavy on paperwork and limiting liability, while staff in Winnipeg dedicated to advancing science lament red tape and onerous reporting requirements.

Gary Kobinger, a researcher who was instrumental in developing the Ebola vaccine, similarly encountered a tension in the lab between its original purpose — diagnostics and forensics tests — and scientists’ secondary role in researching pathogens.

“I found it surprising that some people were questioning the research mandate, when you have so much support, clearly from all the entire chain of command,” said Kobinger, who now works out of Université Laval in Quebec City.

During his term, Ottawa and Winnipeg butted heads over the licensing of the Ebola vaccine, which was done in part to satisfy belt-tightening measures.

PHAC licensed the rights for its vaccine to an American company for $205,000 in 2007, which the firm then flipped to drug-manufacturing giant Merck in 2014 for US$50 million. In a June 2015 report to Parliament, PHAC stated it had collected roughly $6 million in royalties; as of this month that number hasn’t changed.

People working within PHAC’s Ottawa headquarters argue the government massively undersold its research, and felt under pressure when parliamentarians demanded to know how the manufacturing rights were sold for 250 times what Ottawa had collected.

It was under this context that PHAC appointed Gilmour to lead NML, starting in early 2015.

Gilmour had worked at the lab and in Manitoba’s health system, overseeing research in intestinal diseases. He was hired after the controversy surrounding the initial job posting, which focused heavily on bureaucratic experience instead of scientific knowledge.

Since Gilmour took over, protocols have been followed more strictly, a move many at the lab welcomed.

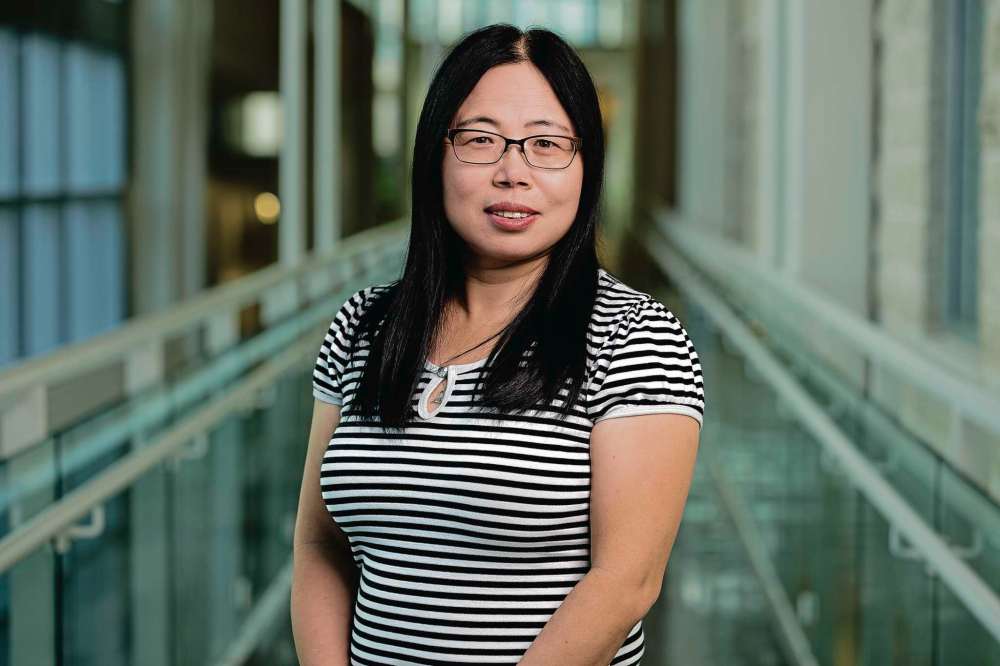

However, there have been times Winnipeg staff have felt under the gun from Ottawa, such as this summer’s explosive news of Xiangguo Qiu, a biologist from China, being ushered out of the lab.

In March, Qiu sent samples of the Ebola and Henipah viruses to China; sources previously told the Free Press that intellectual-property protocols were not followed. That shortcoming was first flagged by officials in Ottawa, after the sample had already left Winnipeg.

Some employees have questioned why none of the managers intervened when the samples were being prepared to be sent to China, a process that requires numerous approvals and live tracking during the shipping process.

Managers were aghast and furious when media got wind of the incident, and have implemented “PHAC values” training for staff, which includes not leaking to media.

The incident hit the news in July, after PHAC removed Qiu, along with her husband, biologist Keding Cheng from the lab, and asked the RCMP in May to probe “possible policy breaches.”

Some alleged favouritism, believing that the lab’s most prominent researchers evade scrutiny from higher-ups. Others feel PHAC overreacted, with Ottawa higher-ups scorned by the Ebola-vaccine controversy and now over-diligent about paperwork.

The finger-pointing is evident in internal emails, such as a July 17 message Kingyens wrote to senior management — which Kingyens herself did not provide to the Free Press. She asked that union officials be present if PHAC starts questioning employees working in the specimen shipping-and-receiving area.

“Any processes our members performed at the request of Qiu or Cheng were done as per the standard operating procedures, and with the understanding that what was received or shipped was recorded in the transport documentation,” Kingyens wrote.

“There was no requirement to examine or verify the identity of these specimens shipped or received,” she wrote, asking that the union be made aware if shipping-dock staff are questioned about “any duplicity by Qiu or Cheng.”

Qiu declined an interview request about the situation.

“Everything’s hush-hush; they don’t want anything to get out. The NML is a toxic workplace.” – Todd Panas, national president of the Union of Health and Environment Workers.

As of midweek, the RCMP is still investigating the incident and refuses to say which branch — national security, organized crime or forensics — is in charge.

“In order to maintain the integrity of the investigative process, we have no further comment at this time,” wrote Manitoba RCMP spokesman Robert Cyrenne.

Numerous employees say they want officials to clarify the situation, especially after media reported conjecture about spying and bioterrorism, when the concern seems to surround liability, intellectual property and the lab’s reputation.

Many of them said the spirit of the posters and cue cards about mental health and safe workplaces fly in the face of pushing someone out of the lab without clarifying why.

Kobinger said he hopes his former workplace can find the right path. He noted that the laboratory is uncommonly public about its safety-protocol breaches and has worked hard to be transparent, but seems to lack the the same approach when confronting issues internally.

“I find it a bit alarming and sad that people are losing trust,” he said. “It’s a top-of-the-line, stellar facility and the people working there are superb scientists.”

Kingyens says morale at NML is improving, thanks to measures such as mental-health breaks. She cautioned against seeing worse-case anecdotes as the full picture of working at the lab.

“You’re always going to find someone disgruntled, I think at any workplace. We try to help our people as much as possible, and try to bring it up to senior management’s attention when lower-level management is not being respectful or following the regulations.

“Our senior management is very conscientious of their responsibilities, in terms of taking care of mental health in the workplace, and I have every confidence in them,” she said.

But for Panas, there needs to be more accountability, such as transparency around who gets promoted at NML and clear consequences for inappropriate behaviour. Until then, he expects to keep getting calls from distressed employees at the lab.

“Everything’s hush-hush; they don’t want anything to get out,” he said. “The NML is a toxic workplace.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

Government responses and documentation on issues at National Microbiology Lab

History

Updated on Monday, September 30, 2019 1:19 PM CDT: Tweaks attribution in paragraphs regarding training and conference attendance and bullying/intimidation reports.