New weapons in meth battle Drug-psychosis simulation, anti-psychotic pill helping Winnipeg police defuse potentially violent users

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/02/2019 (2044 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Last summer, a man high on methamphetamine strapped metal plates on his limbs, went outside and encouraged Winnipeg police officers to shoot him before they arrested him.

Last October, a 26-year-old man high on meth brandished metal shears and a piece of rebar while kicking and threatening Winnipeg police officers.

And in two separate incidents last month that occurred within a few hours of each other, two men — both high on meth, armed with machetes and still in possession of the drug — were successfully taken into police custody.

These are the types of incidents which not long ago might have easily ended up with police officers using deadly force to protect bystanders, as well as themselves.

But in each of these cases, and many others, deadly force was not used. Officers didn’t even have to fire a Taser.

It leads to the question: has something changed with how Winnipeg police handle such incidents?

###

"You’re making dumb choices." "Nobody likes you". "You should have killed yourself a long time ago." "Police are trying to trick you." "Don’t put down the knife."

I’m holding a knife — albeit made of rubber — and these are the words I hear through wireless earphones. They’re coming from both men and women, and they are coming in increasing urgency, as I go through a scenario mimicking what a person in a meth induced psychosis experiences. It’s an auditory hallucination simulation and the voices are non-stop, going from loud to soft, sometimes overlapping, but the advice, if you can call it that, is always negative.

Hear what trainees hear

Listen to the auditory hallucination simulation.

Listen to the auditory hallucination simulation. Headphones are recommended.

Grey: Generic voices

Red: Police enter, hostile voices

Yellow: Voices start to become less hostile

Green: Voices support police/giving up weapon

Jeff Quail, CEO of Setcan, which produces officer safety products and training, and who himself is a retired Winnipeg Police Service officer, is peering around a doorway, trying to get his voice to talk through the voices I’m hearing, to convince me to drop the weapon. It’s a simple scenario, but it is one that offers a brief window into the mind of the person going through drug-induced psychosis.

After the simulation, called SimVoice, concludes, both Quail and a Free Press photographer agree the gaze on my face during the exercise was far different than it was earlier when the scenario was run without the audio being used.

Quail, whose company has given the SimVoice system for free to 250 police departments across North America in the year since it was developed, said the device "is all about creating compassion through the experience.

"They realize ‘wow, this is really difficult for them’," he said. "By experiencing it on the other side, by having auditory hallucinations, you can start experiencing what it is like to have voices in your head.

"We’re trying to help police make better decisions under stress. If you can make officers act better under stress, there is less a likelihood of them pulling the trigger.

"What’s a life worth? How do you put a value on that?"

Quail said he was sitting in a training session when "I had an aha moment" about the need for officers to get a better idea about the outlook of people in psychosis experiences.

But Quail said even with the SimVoice, and all the other training police officers are given, the conclusion of an incident in real life still ultimately comes down to the individual who is going through the meth-induced psychosis.

"It’s a 100 per cent win when no one is injured, but the truth is, there’s a false belief it is the police officer’s decision. It is the individual’s decision what happens."

XXX

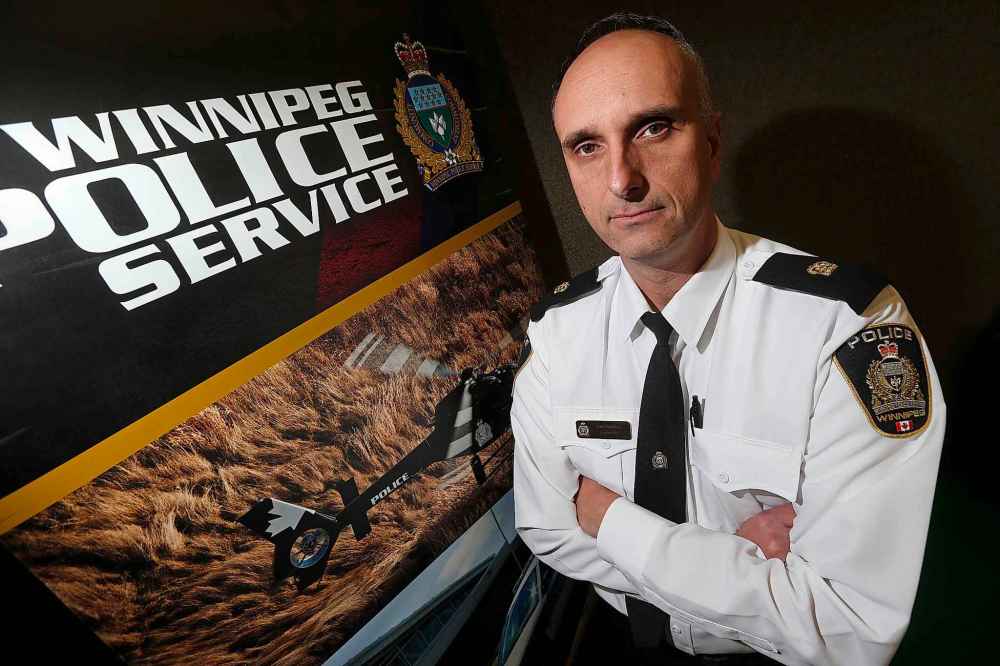

Down at Winnipeg police headquarters, Deputy Police Chief Gord Perrier, Insp. Max Waddell of the organized crime unit, and Dr. Rob Grierson, the service’s medical advisor as well as medical director for the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service, say the recent successful outcomes are the result of years of work and training in both mental health and use of force by the service’s tactical response team, new training methods like the SimVoice, and an anti-psychotic drug that has just recently been approved to give to people going through meth-induced psychosis.

Perrier said he has gone through the SimVoice training himself and was impressed.

"It is genius," he said. "I automatically could see the reaction in the officers’ faces and my face too — because they taped it — was exactly the same as a person who is sometimes suffering schizophrenia because it overloads so many things.

"When you role reverse, and you become the police officer, there’s something different that happens… you are reading that situation way deeper than you may have been before.

"You’re looking at the weapon and intent a little differently and there’s an automatic empathy build that is occurring because you have experienced that other way."

Grierson said police officers are also treating people having psychosis episodes on meth the same as people having schizophrenic episodes because they present the same way.

"You can virtually not tell the difference," he said.

"(Meth) is mimicking the same thing to the brain schizophrenia does … we have a strategy to help people with schizophrenia and you can use that same strategy to help people with methamphetamine.

(imagetagRight)

"The strategies which work with one will work with the other. You just have to have the patience and the understanding of that."

And Perrier said calling the training "de escalation use of force", instead of just use of force, emphasizes the possibility of resolving the situation without using a weapon.

"It doesn’t mean that if somebody presents a legitimate weapon, somebody presents a legitimate intent, and that threat level, that we’re not going to do our job that’s expected of us and deliver force to end that situation," he said. "Nothing has changed there.

"Because of those small changes in training, that small changes in additional training, and peoples’ lived experiences, I think we’re seeing some outcomes that could be different."

Perrier said there’s another sobering reason for the positive outcomes in recent weeks: practice makes perfect.

"Police officers get good at dealing with something they deal with on a regular basis. We deal with this every day, day in and day out… people become good at it because they deal with it so often."

The statistics are stark and show the problem of methamphetamine is still rising in the community. Just a month ago, Winnipeg police held a press conference showing the more than $1 million worth of meth they had seized in the weeks before. A year earlier, seizures were in the thousands of dollars.

And, just two years ago, methamphetamine wasn’t the problem, fentanyl was.

Waddell said because "we were so focused on fentanyl, but, at the same time, I call them the quiet user group, was gaining momentum with methamphetamine… fentanyl in 2017 really started to tail off and that’s when methamphetamine just really ramped up and you see it where it is today."

Waddell said because meth is a stimulant while fentanyl is a depressant, their effects on people are very different when police arrive.

"You’re not as likely to act out in such a violent state with a fentanyl addiction as you would with a methamphetamine addiction because the way (meth) alters the brain makes you more unpredictable in a state of psychosis."

And, with fentanyl at $60,000 per kilo and meth at $17,000, Waddell said that also made it spread faster among users.

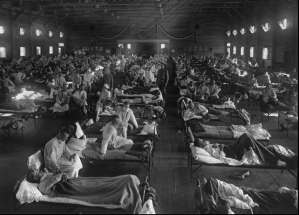

Statistics from the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service show that while paramedics attended 771 meth-related incidents in 2017, 2018 saw that figure rise to 1,166.

Grierson also said paramedics have had to pull out olanzapine, an anti-psychotic drug usually used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and a drug which paramedics began using on Dec. 4, after the province gave them the green light on people having psychosis episodes with meth, more than he predicted.

"We were the first place in Canada that provided that medication to paramedics," he said. "In the first month we gave the drug successfully 72 times to people.

"Now it’s a good news and a bad news story. The bad news is we had to give it to 72 people. The good news is we had it and people were able to take it.

"You see these people, they’re agitated, they’re anxious, they’re not violent, but they’re frightened… you come in a calm, reassuring voice and say we’re here to help, we’re not going to lock you up, we’re not going to tie you up, and… I’ve got a medication that can make you feel better and lo and behold people are taking it."

In the end, Perrier said, there’s no way to know for sure how an incident will end, especially when you toss meth into the mix.

"With all of the training that they have, at the end of the day, they are really trying to predict what a human will do… there’s some parts of it that are reliable, but there are large gaps still.

"There just is."

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason

Reporter

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.