Vaccine goal must be global

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/01/2022 (1437 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On Dec. 14, 2020, amid the dark, deadly days of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, an 89-year-old Quebec woman named Gisele Levesque sat down in a leather arm chair and made history.

She became the first person in Canada to receive a COVID-19 vaccine.

Now, a little more than a year later, over 64 million vaccines have been administered from coast to coast to coast, with people rolling up their sleeves to get their first, second and now third jabs as part of a worldwide vaccination campaign.

Indeed, the year 2021 was, in many ways, the Year of the Vaccine — so much so, “vaccine” was crowned Merriam-Webster’s word of the year.

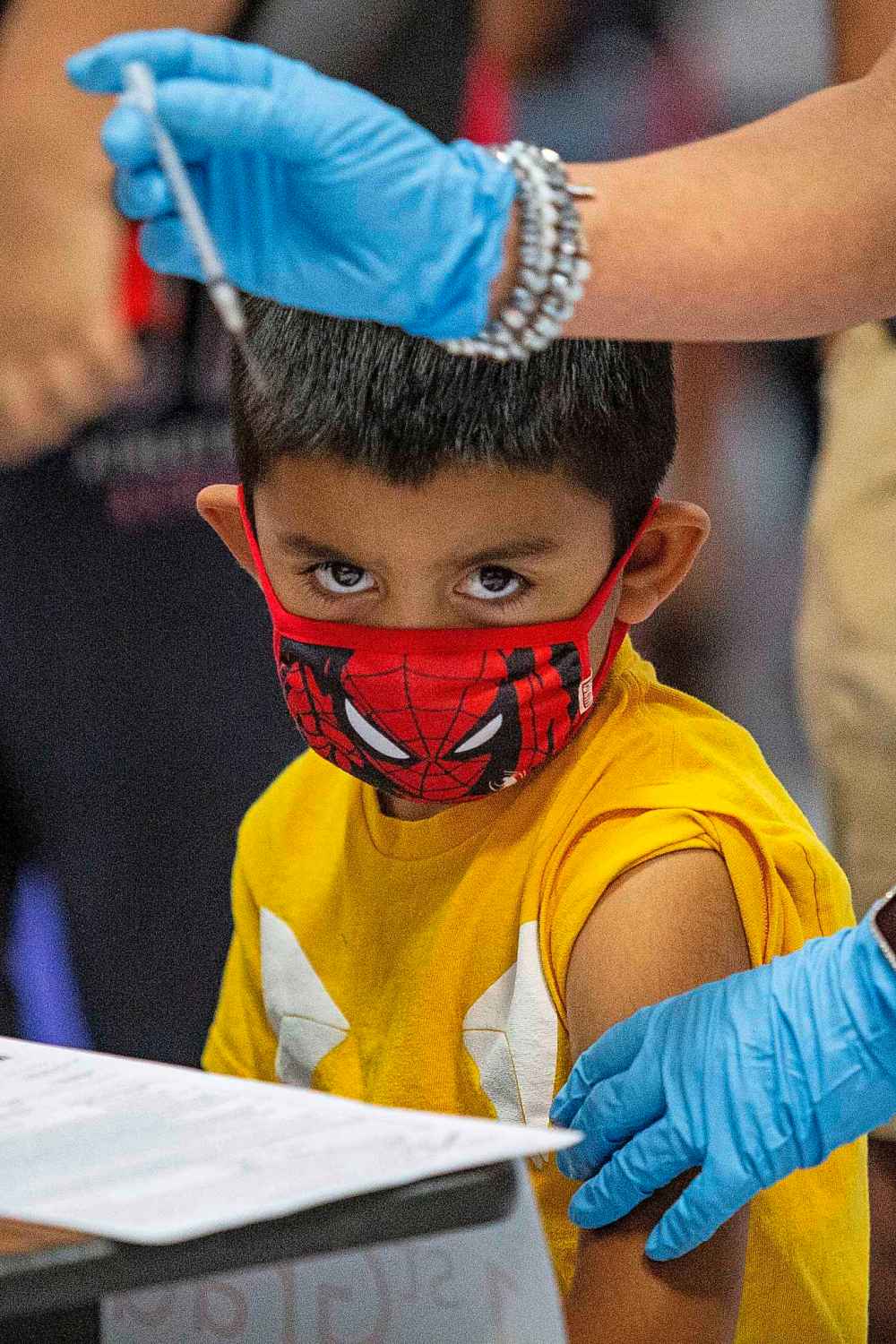

For many, vaccines represent hope in a vial, a marvel of science and public health, a safe and effective way to get back to the people, places and lives we’ve so desperately missed — and, most important of all, a way to protect ourselves and each other. As winter gave way to spring and shots got into arms, the excitement and relief was palpable. People bought Team Moderna and Team Pfizer T-shirts. They shared screenshots of their appointment bookings. That excitement was echoed again in the fall, when vaccines were approved for Canadian kids aged five to 11. The youngest in that cohort, it’s worth mentioning, has never known a school year without masks, distancing or remote learning.

Despite being an impressive new tool in our arsenal, vaccines have also been a site of misinformation, distrust, conspiracy theories and fear, all of which amount to major roadblocks in the fight against COVID-19.

Here in Manitoba, the story of vaccination isn’t just of post-vax smiles behind masks and bright green stickers declaring “I’m COVID-19 Vaccinated”. It’s also one of division, particularly in the Southern Health region of the province, where vaccination rates remain stubbornly low and anti-vax rhetoric has taken deep root.

The summer saw anti-vaccine rallies across the country, including in front of the very hospitals in which frontline workers took care of COVID-19 patients on ventilators. Social media was flooded with debates about the ethics of vaccine mandates and passports.

While 76 per cent of Canadians have two doses and 81 per cent have one, too many Canadians are still not yet vaccinated. Not all of those people are ardent anti-vaxxers, either; vaccine hesitancy is a complicated issue. As Dr. Anita Sreedhar and Anand Gopal recently wrote recently in the New York Times, “Hesitancy is a global phenomenon. While the reasons vary by country, the underlying causes are the same: a deep mistrust in local and international institutions, in a context in which governments worldwide have cut social services.”

And now, we’re ending the year with yet another round of restrictions and a race to get boosters into arms as Omicron, a highly contagious new variant, disrupts our lives yet again. Hesitancy isn’t the only stumbling block to herd immunity; the next chapter of the vaccine story must be about vaccine equity. As the World Health Organization has underlined many times, the virus is outpacing the global distribution of vaccines, which will mean contending with new variants of concern, which will mean more restrictions and disruption — and, more critically, more illness and death.

Some bold action will need to be taken by governments of wealthy countries — including Canada — if we want to ring in 2023 with the pandemic in the rear-view mirror.