Saving children is costly, past due

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/08/2014 (3739 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

THE death of Tracia Owen in 2005 was a wake up call for social services in this province. She hanged herself, having been repeatedly betrayed by a family to whom she was sure she would return, permanently, one day. At 14, the chronic runaway who was sexually exploited on the streets saw death as preferable.

Ms. Owen was moved some 64 times by Child and Family Services. The inquest into the failed involvement of CFS in the girl’s life gave rise to Tracia’s Trust, the co-ordination of a variety of services, including police, in Winnipeg and Thompson that respond to take children at risk off the streets.

Among the responses introduced is the non-voluntary confinement of boys and girls, a sort of crisis intervention to pull exploited children out of dangerous circumstances and, for a limited period, work to get them stabilized and safe. Street Reach, an emergency response to find youth on the streets, identified some 240 such children last year, and located and returned youth to safety more than 400 times.

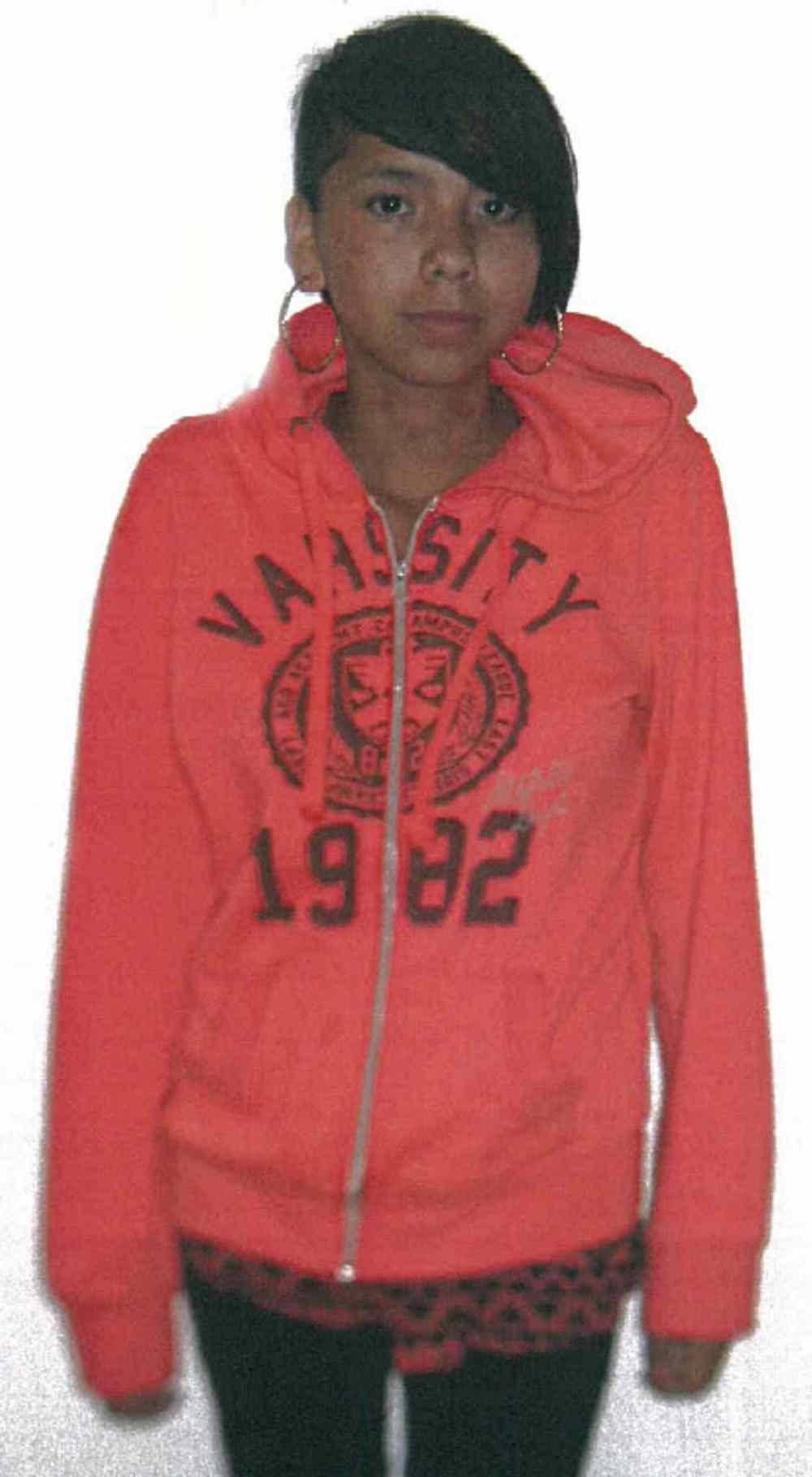

Heroic measures, however, did not save Tina Fontaine, a runaway known to police. The 15-year-old’s body was pulled Sunday from the Red River by the Alexander Docks, tied in a plastic bag. Police, usually cautiously circumspect, have said publicly she was murdered.

Aboriginal groups again are demanding a national inquiry into this country’s long list of missing and murdered aboriginal women. Tina Fontaine was from the Sagkeeng community, north of Winnipeg and was on the run from CFS since Aug. 9 before her murder. She fits, in many ways, the “profile” of both a child in danger of exploitation and of a woman at elevated risk in this city just because they are aboriginal. An RCMP report this year found since 1980, more than 1,200 women have gone missing or been murdered in Canada, and aboriginal women make up 16 per cent of the homicides and 11 per cent of the missing cases, despite being less than five per cent of the population.

Tracia’s Trust was created by the community’s experts to curtail risk, stem the violence and save the children. That is hopeful stuff: For every child lifted from the street, social-service workers say there are dozens more out there, on the run from authorities or simply away from home, looking for a happier place to be.

One answer is prevention, the expensive and time-consuming job that puts resources into the neighbourhoods, so parents struggling or incapable of doing the job can get help to raise their kids. Manitoba has the highest rate of taking children into care of CFS, a sign social services aren’t up to the job and they arrive too late.

The Office of the Children’s Advocate, by law, will review CFS involvement with Tina Fontaine to assess the agency’s provision of care. Repeat inquests in past cases have pointed to lack of worker training, inadequate resources for troubled youth and their families, a lack of oversight and heavy workloads. The list goes on.

Children on the run are good at evading the police and child-welfare workers. Predators know how to spot them, give them a place to sleep, something to eat.

The inquiry into the death of Phoenix Sinclair revealed her parents — both one-time wards of CFS — were good at avoiding agency workers. They instead found unconditional friendship, advice and help at the Boys and Girls Club in their North End neighbourhood. And that worked, as long as it lasted.

It’s not a long-term solution to the range of complex responses required for a child in dire need. But people with an intense distrust of official agencies will look for a safe harbour, a drop-in centre where help’s available and not a threat.

Responses such as Tracia’s Trust should look to peppering local haunts of street teens with drop-in sites. The best way, however, to keep children from falling into risk is keeping their homes safe. That’s expensive, and made complicated by Canada’s history of mistreatment of aboriginal people. But the alternative is the indecent toll paid through inquests, suicides and the mounting numbers of murdered or missing aboriginal women.

History

Updated on Wednesday, August 20, 2014 7:24 AM CDT: Replaces photo